The Human Being as Body, Soul and Spirit

GA 347

27 September 1922, Dornach

Automated Translation

IX. The Dawn of Time

Last time I talked to you about the moon flying out of the earth and how that is connected to life on earth in the first place. I can already imagine that you will have many questions. We can deal with them next Saturday. Think about some of them by then. But today I still have a few things to discuss. Some questions may arise.

We have said: As long as the moon was inside the earth, what can be called the reproductive power of animal beings was quite different than later, after the moon had flown out. I have told you that in the time when the moon was still inside the earth, the moon gave the earth those forces that are, so to speak, maternal forces, feminine forces. So we can imagine that there was a time when the moon was still inside the earth. I will sketch this out for you very schematically.

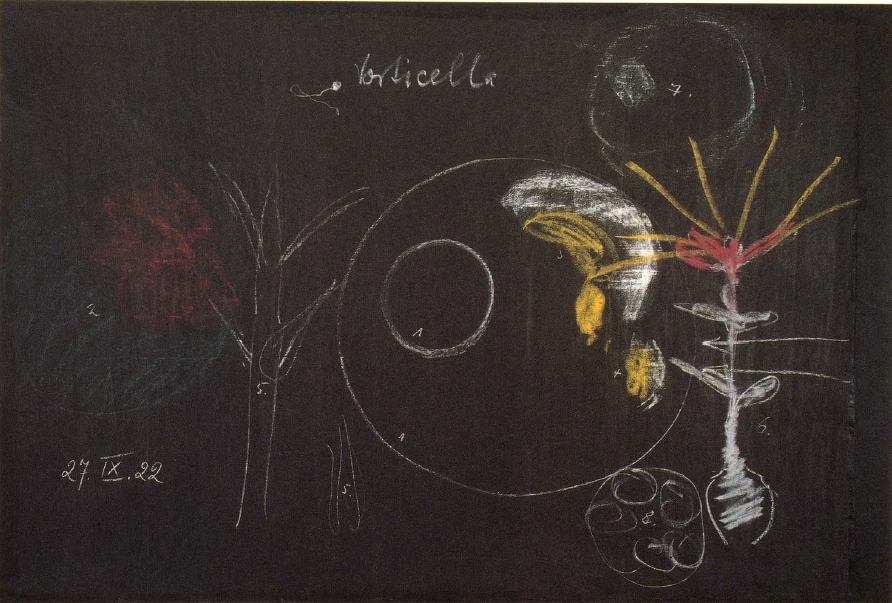

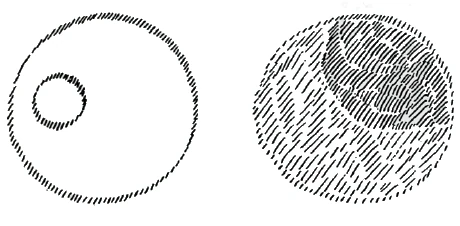

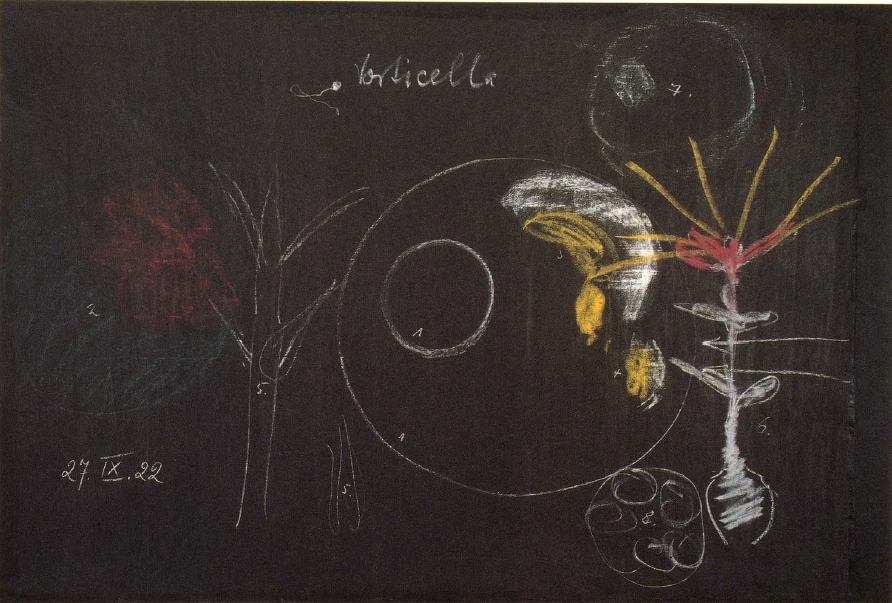

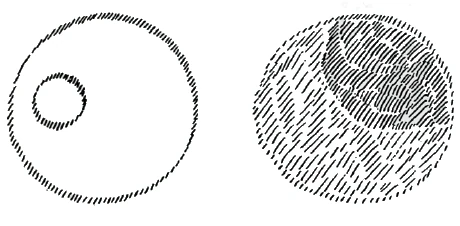

When the moon was still inside the earth, it was not in the center, but a little to the outside (see drawing, left). If you look at the Earth today, you will also notice that on one side, more towards where Australia is located, there is a lot of water on the Earth, while on the side where Europe and Asia are located, there is a lot of land. So the Earth actually does not have land and water equally distributed, but the Earth is such that on one side it actually has the most land and on the other side the most water. So the material on Earth is not evenly distributed (see drawing $.149, right). It was also not evenly distributed when the moon was still inside the Earth. The moon was just lying on the side where the Earth has the inclination to be heavy. Of course, if there is a solid material, it is heavy there. So I have to draw it the way I have marked it there with white chalk.

Now you have to imagine that at that time fertilization took place in such a way that the moon, which was inside the earth, gave these giant creatures the strength to, so to speak, provide reproductive material. You can't say that back then the animals would have laid real eggs. These giant oysters were actually just a slimy mass themselves, and they just secreted a piece of themselves. So that such a gigantic oyster, as I described to you last time, which could originally have been as large as the whole of France, had a mighty shell on which one could have walked around, and towards the interior of the earth a mass of slime. The lunar forces worked on this slime, and a piece of it was secreted. That then swam further into the earth. And when the sun shone on it again – I have explained this to you vividly using the example of the dog – an egg shell was formed, and because this egg shell was formed, the slimy mass of the oyster was again inclined to secrete a piece of itself, and then a new animal could arise. So the female forces came from the moon, which was in the earth, and the male forces from the sun, which shone on the earth from the outside. Now, gentlemen, I am describing a very specific time, the time when the moon was still inside the earth.

Now you have to imagine the following. Today, when the moon is outside, outside the earth, it has a completely different effect. You also know that when carbonic acid is inside a person – I told you this last time – it has a completely different effect than when it is outside, where it is a poison. If you recall animal reproduction today, you must say: the animals have to produce eggs, and these eggs must then be fertilized in some way. So what the moon used to give when it was inside the earth is now in the animals. The animals have these lunar forces within them.

And the moon also gives forces from the outside. I told you last time: even poets know that the moon gives forces to the earth. But these are forces that stimulate the imagination, that make you more alive inside. These are forces that no longer affect reproduction, but that radiate in from the outside and can no longer effect reproduction at all.

So you have to imagine it: what the moon was able to give the earth when it was still inside, these reproductive powers, the animals have appropriated them, inherited them, and now they plant them from one animal to another. So when you look at the eggs of the animals, you have to say to yourself: the lunar forces are inside. But those lunar forces are still inside that worked when the moon was still in the earth. Today the moon can no longer do much other than stimulate the head. So today the moon works on the head. But in those days it worked precisely on reproduction. You see, that is a considerable difference. It makes a big difference whether something is inside the earth or outside of it.

Reproduction is a very strange thing. But again, we have to say that all understanding of nature depends on understanding reproduction. Because through it, the individual animals and the individual plants still arise today. If it were not for reproduction, everything would have died long ago. If you want to understand anything about nature, you have to understand reproduction. But reproduction is something peculiar on earth.

Just imagine: the elephant has the peculiarity of only being able to produce a single young at around fifteen or sixteen years of age. Take an oyster, on the other hand; it is a small, slimy animal. If you imagine this as being huge, you will have roughly the same creatures that I showed you for that time. So, you can learn something from an oyster. But the oyster is not like the elephant, which has to wait so many years to produce a young one. A single oyster can produce a million oysters in a year. So an oyster has a different relationship to reproduction than an elephant.

Now, gentlemen, another interesting animal is the aphid. You know that it occurs on the leaves of trees and can be found as a rather harmful population of the plant world. People suffer a lot from it. An aphid is, as you know, much smaller than an elephant, but it can produce several thousand million offspring in just a few weeks – a single aphid! An elephant, for example, needs about fifteen or sixteen years to produce a single offspring, but the aphid can reproduce in just a few weeks to produce several million from a single individual.

And then there are tiny animals called vortices. If you look at them through a microscope, they are just a tiny lump of mucus, and they have a thread that they wriggle along. They are very interesting animals, but they consist only of a tiny lump of mucus, like if you took a thread out of an oyster, and they swim around like that. These little Vorticelles are now able to produce a hundred and forty trillion offspring in four days – a single one! – so many zeros would be needed to write it on the blackboard. The only thing that can compete with that now is Russian currency!

So you see, there is a considerable difference in reproductive capacity between an elephant, which has to wait fifteen or sixteen years to produce a single young, and such a small Vorticella, which in four days multiplies to such an extent that one hundred and forty trillion offspring grow.

So you see, there are really very significant natural secrets here. And there is a very interesting French tale, which on the surface doesn't have much to do with it, but inwardly it does. There was an important French poet — his name was Racine. And this Racine, it took him seven years to write a play like “Athalie”. So he wrote a play like 'Athalie' in seven years. And in his time there was another poet who was terribly proud compared to Racine and said: Racine needs seven years to write a play; I write seven plays in one year! And so he came up with a fable, a story, and this story, this fable goes: the pig and the lion were once arguing; and the pig, who was proud, said to the lion: I have seven young ones every year, but you, lion, you only produce one in a year. — Then the lion said: Yes, but the only one is a lion, and your seven are pigs. And with that, didn't Racine want to brush the poet aside. He didn't exactly want to tell him that his plays were pigs, but he compared them, because he said: Well, you do seven plays like that every year, but in seven years I do one Athalie – which is world-famous today.

You see, you can say: Even in a fable like that, in a story like that, there is something to be said for taking fifteen or sixteen years, like an elephant, to have a young one, rather than being a Vorticelle, which reproduces in four days to have a hundred and forty trillion young. People already talk a lot about the fact that rabbits have so many young; if they only started talking about the Vorticelle – it's impossible to imagine such a reproductive capacity!

Now, we have to find out why such tiny animals produce so many young, while it takes an elephant so long.

Now I have told you: the sun is the actual basis for fertilization. So, even today, we still need the sun for fertilization. And I have also told you: if there is a heavenly body outside, like the moon, it only affects the head at most, but no longer affects the abdominal organs, so no longer directly affects the reproductive powers. Today, the reproductive powers must be inherited from one being to another. But, gentlemen, in a certain sense, what happens in today's reproduction is still dependent on the moon. And I will explain this to you in the following way, by going back to the sun again.

You see, we have to ask ourselves: Why does an elephant need fifteen or sixteen years to develop its reproductive ability to the point where it can have a calf? Now you all know that the elephant is a pachyderm, and because it is a pachyderm, it takes so long. A thick skin allows the sun's forces to pass through it less strongly than if you were a plant louse and were very soft and the sun's forces could get in everywhere. So the elephant's low fertility is actually related to its thick skin.

You can also tell by the fact that Think back to those huge floating oysters. Yes, a second oyster would never come into being if it only depended on the sun shining on that scale armor, on that thick skin! But this oyster, as I told you, releases a little mucus; the mucus does not yet have an oyster shell, so the sun can come upon it. And by drying the mucus and thereby creating a new oyster, it has a fertilizing effect on that oyster. Yes, when the sun's rays come from the outside, gentlemen, they can only create shells. How is it that the forces of the sun can still have a fertilizing effect?

You see, we have to look at something else to help you understand how the story actually fits together. You may know that when the farmers have harvested the potatoes, they dig quite deep pits and put the potatoes in them. Then they cover the pits again. And then later, when the winter is over, they dig up the potatoes from these pits again, because they have remained good in there. If they had simply kept the potatoes in the cellar, they would have perished. They stay quite good in there.

Where does this actually come from? It is a very interesting thing. The farmers don't know much about it. But, gentlemen, if you were a potato yourself and were buried in this pit, you would actually feel extremely good in there, if you didn't need something to eat. You see, the warmth of the sun in summer remains in there, and what the sun shines on the earth in summer, that draws more and more downwards. And if you dig into the earth in January, the warmth of the sun and all the other solar forces from summer are still there at a depth of one and a half meters.

That is the strange thing. In summer, the sun is out and warms from the outside, and in winter, the sun's power moves down and can be found further down. But it cannot go very deep down; it flows back up again. If you were a potato and were lying down there, you would be quite comfortable; you wouldn't need to heat up, because first of all there is still the warmth from the summer inside, and secondly it comes up quite warmly from below because the solar forces radiate back again. And these potatoes are actually terribly comfortable. It is only there that they really enjoy the sun. In summer they don't get much of the sun, it's even unpleasant for them. If they had heads, they would get headaches when the sun shines on them; it is actually unpleasant for the potatoes. But in winter, when they are buried in the earth, they can really enjoy the sun.

From this you can see that the sun does not only work when it shines on something, but it continues to work when its energy is absorbed and stopped by something.

Yes, gentlemen, now a peculiarity occurs. I have told you: When a body is outside the earth, it has a killing effect, either - like carbonic acid - like a poison, or like the sun here, which produces dandruff when it shines on it; it hardens the living being on which it shines. But in winter, it is not true that the sun works from the outside; it works from inside the earth. There it leaves its strength behind, working in the interior of the earth. And there it also renews the reproductive forces in the interior of the earth, so that the reproductive forces today, in our time, also come from the sun, but not from direct sunlight, but from what remains in the earth and then radiates back in winter.

It is a very interesting thing. It is just like when we breathe in carbon dioxide: then it is a poison. But when the carbon dioxide is inside our body and goes through the blood, we need it. Because if we had no carbon, we would have nothing at all inside us. We need it inside; then it is beneficial; from the outside it is a poison. Sunlight from the outside causes peeling in animals; sunlight absorbed from within and reflected back generates life and makes the animals capable of reproduction.

But, gentlemen, now imagine that you are not a potato but an elephant. You would have an awfully thick skin and would only let a little of the warmth that the earth has from the sun in. That is why it would take you an awfully long time to produce an elephant calf if you were an elephant. But imagine you were a plant louse or an oyster; in that oyster you would be just a mass of mucus near the earth's surface. The elephant is not such a mass of mucus. The elephant is closed off on all sides by its skin, so it lets this warmth, which comes from below, into itself only very slowly.

Now, you see, it is like this: animals like aphids, which also live close to the ground and on plants, have no thick skin at all; they can absorb what evaporates from the earth with the spring with terrible ease, so their reproductive powers are always quickly refreshed. And the vortices even more so, because they live in the water and water retains the warmth of the sun much more intensely, so that the stored solar warmth in the vortices produces the hundred and forty billion at the right season; that is, when they have absorbed enough of what the warmth of the sun is in the water, they can reproduce themselves terribly quickly. So we can say: Today, the Earth gives its beings the ability to reproduce by storing the forces of the sun within itself during the winter.

Now let us move on from there to the plants. You see, with plants it is like this: you know that plants also reproduce through so-called cuttings. So when a plant grows out of the earth, you can cut a cutting somewhere. You have to cut it out properly, then you can plant it and it will grow into a plant. Certain plants reproduce in this way. Where does that come from? The reason why plants have the power to reproduce even through a piece of themselves is because they have the seed in the earth during the winter. That is a very important thing for plants. If you want to somehow encourage plants to grow properly, it is the case, isn't it, that they actually have to be in the ground during the winter. They have to grow out of the ground at all. There are summer fruits, and we could talk about them later. But in the main, the plants have to develop their seeds in the soil, and then they can grow. Sometimes you can also make bulbous plants grow in water, but you have to take special measures for that, don't you. In nature, it is mainly the case that plants have to be placed in the soil and have to get their strength to grow from there.

What happens, gentlemen, when a seed is placed in the earth? There this seed is really placed in the beneficence of absorbing these forces given by the sun to the earth. The plant seed, in particular, really absorbs these forces that come from the sun into the earth.

With animals, it is much more difficult. Those animals that are actually in the earth, such as earthworms and the like, also easily absorb this power. That is why they all reproduce very prolifically, all the animals that are either very close to the earth or in the earth. Worms are also such that they have an awful lot of offspring, and for example just such worms, which unfortunately can also get into the human intestines, produce an awful lot of offspring, and man must constantly exert his own powers so that these worms do not produce an awful lot of offspring. So that if you have worms inside you, you have to use almost all your vital forces to kill these horror stories that you have inside you.

Yes, but plants are able to grow out of the ground (see drawing); down there is the root, then they grow out of the ground, and then they have the leaves, then they develop the flowers and new seeds. But, gentlemen, you know very well that when the flower begins to develop, the plant no longer grows upwards. That is very interesting. The seed of the plant, the germ, is placed in the soil; the stalk grows out of it, leaves, green leaves, and then the flower comes. There the growth is stopped, and the plant now quickly produces the seed. If it did not produce the seed quickly, the sun would use all its strength on these petals, which would be infertile. The plant would get a huge, beautiful flower at the top, with many colors, but the seed would not be able to develop. The plant finally gathers all its strength to produce the seed quickly.

You see, the sun that comes from outside has the peculiarity of making plants beautiful. When we find beautiful plants in the meadow, it is the external sun with its rays that brings out these beautiful colors. But it would make the plants die with it, just as it makes the oyster die with the oyster shell, dries up.

That is why you can see this all over the world. You can see this effect of the sun particularly well when you come to hot, equatorial regions; there all the birds are in the most wonderful colors. That is the effect of the external sun. These feathers are all beautifully colored, but they no longer contain any life force. The life force is most dead in the feathers.

And so it is with the plant. When it grows out of the ground, it has abundant life force. Then it loses more and more of it and in the end it has to gather all its strength; it still puts the very little bit of life force into the seed. And the sun makes beautiful leaves, colorful flowers, but in doing so it kills the plant. There is nothing of reproductive capacity in the colored petals.

But what does the plant do when its seed is placed in the earth? It does not just allow itself to be placed in the earth, but it brings forth growth in the leaves; it brings that forth. If I draw something green, the forces of the sun, that is, warmth, light and so on, develop it. So the forces of the sun rise up in the plant. The plant takes these with it in the seed, while the solar forces that come from outside kill the plant, so that a very beautiful flower arises. But in the middle of it all there is still the seed, which comes from the solar warmth stored up in the middle of winter. The seed does not come from this year's sun. That is just a misconception. The beautiful blossom comes from this year's sun; but the seed comes from the solar warmth of the previous year, which still has the strength that the sun first gave to the earth. The plant carries this through its entire body.

This would not be so easy for animals. The animal depends on the fact that this solar warmth comes more from outside, more from the earth, and is only refreshed. This is because the animal does not absorb the forces of the sun as directly as the plant. But the plant carries the warmth of the previous year's sun through its own body up to the seed in the flower, which has accumulated in the earth.

If you look at this story correctly – it is extraordinarily interesting, wonderfully interesting – then you say to yourself: plants and animals reproduce. They could not reproduce if the sun did not work. If there were no sun, they could not reproduce. But the sun, which is out there in the sky, apart from the earth, it is precisely what kills the ability to reproduce. It is the same as with carbonic acid: when we inhale carbonic acid, it kills us; when we have it inside us, it invigorates us. When the earth receives the sun's rays from outside, its animals and plants are killed; when the earth can give the animals and plants from its interior what is in the sun, they are invigorated and stimulated to reproduce. You can see that in plants; they develop seeds capable of reproduction only from the power of the sun, which they take with them from before, from the previous summer. What makes the plant beautiful this year comes from this year's sun. It is like that in general: the inner life grows from the past, and one becomes beautiful through the present,

Now, gentlemen, the elephant with its thick skin, but the little warmth from the earth and the little sun inside, which he gets from the earth, would be of little use to him, because he is a pachyderm. These forces do not pass through him so easily. He must have stored up a great deal of his own semen from earlier. He has stored up lunar forces. He needs them, of course, for maternal, for female reproduction. He has stored them up. The moon has emerged from the earth, and the animals that reproduce have the lunar forces within them.

You see, there is something that must be taken into account. Of course, someone could come and say: There is such a stupid fellow who says about the former, the earlier lunar forces, that such old forces still live in the eggs, in the reproductive forces. This stupid fellow claims that the present reproductive forces are from the past. – I would simply say to that person: Have you never seen that something that is alive now has something in it that is from the past? – I would show him a boy who looks so much like his father that he is, as they say, the spitting image. Yes, if you then go back – the father could even have already died; someone could have known the father when the father himself was a boy as small as the boy is now, and the person in question could say: Yes, the boy is the spitting image of his father. – But he looks just like him, the way the father was when he himself was a little boy. What you saw there thirty or forty years ago is still in the little boy now! The forces of the past are always still in what lives in the present. And so it is with the reproductive forces. What is in the present comes from the past.

You know, it was considered a particularly strong superstition that the moon should affect the weather. Well, there is also a great deal of superstition in that. But once upon a time there were two scholars in Germany, at the University of Leipzig, one of whom – his name was Fechner – said to himself: perhaps there is a grain of truth in this superstition that the moon affects the weather. So he made a note of what the weather was like at full moon and what the weather was like at new moon, and found that There is a difference; it rains more when the moon is full than when it is new. That is what he found out. You don't have to believe that yet. Such notes are not very convincing. In real science, you have to work much, much more precisely. But he did say that you just have to continue such investigations and see if it doesn't come out that the moon affects the weather.

Now at the same University of Leipzig was another man who thought he was much cleverer – Schleiden was his name. He said: Now even my colleagues are starting to talk about the moon having an effect on the weather. Gosh, that's not true, we have to fight against that with all our might! – Then the Fechner said: Well, the dispute will remain between us men, but we also have women. – You see, that was still in earlier times. When the two university professors lived in Leipzig, the university professors' wives still had an old custom in the city. They put their troughs, their vats, in the rain to get water to wash in. They collected it because water was not easy to come by in old Leipzig. There were no water pipes back then. So Professor Fechner said: Yes, our wives should sort this out. Professor Schleiden and Professor Fechner should do it this way: so that they always get the same amount of rainwater, Professor Schleiden can put out her troughs at the new moon, and my wife can put out her troughs at the full moon! — He said to himself: according to my calculations, she will then get the most rainwater.

Well, you see, the women didn't go along with it. They didn't want to go along with their husbands' science. They couldn't be convinced at all. So it came about in a curious way that a person, even when science is in the form of a man, does not believe in it, like Mrs. Schleiden, and does not say to herself: I get just as much water at the new moon as at the full moon. Instead, she wanted to put out her watering troughs even at the full moon, despite her husband's terrible ranting against Fechner.

That is something that proves nothing. But, you see, it is strange that even today, high and low tides are still connected with the sun and moon. So that one can say: tides occur quite differently during one quarter of the moon than during any other quarter of the moon. That is connected. But, gentlemen, it does not happen because the moon shines on the sea somewhere and that causes a flood, but that is an old story.

When the moon was still inside the earth, it developed its powers and caused the tides. And the earth still has these remnants of the forces themselves, through which the tide arises. No wonder, the earth is already doing it independently. Today it is a superstition to believe that the moon has an effect on the earth. But it once had an effect on the earth when it was still inside, when everything still had an effect on the earth; and the earth is still in this context inside. That is why it determines the tides. But that is only seemingly the case. Just as I look at my watch, I also say: it throws me out at ten o'clock to the hall. — So today the phases of the moon coincide with the tides, because once they were interdependent.

And so it is with the reproductive powers, insofar as they depend on the moon, insofar as they are feminine. And so it is with the reproductive powers, insofar as they depend on the sun, that is, they come from the solar power that is inside the earth.

But all the animals that reproduce so prolifically, up to the trillions, that is, those that can use these solar forces stored up by the sun through the earth, are lower animals. The higher animals and humans have these reproductive powers protected within. Some of the solar power still comes in and constantly refreshes these powers. Without this refreshment, they would not be there either. But from what solar power is inside the earth today, they would not be able to have their reproductive powers properly.

The plant can have them because it carries what lives in the earth from winter into summer through its own body. The plant has the reproductive power from the previous year.

But the elephant cannot have them from the previous year. It has it from a time millions of years ago, and it has it in its reproductive seed, which it in turn inherits from the elephant father to the elephant son. There it is inside. But from what time does it have it inside! Well, just as the plant has the reproductive power of the previous year within it, so the elephant has the reproductive power of millions of years within it. That is why the plant and the lower animals can reproduce from it, because they can still use the power stored up by the earth. These are tremendously strong reproductive powers. Those animals that depend on storing very ancient forces within themselves can only reproduce weakly.

But let us now go back to the time when there were such giant oysters: No sooner had such an oyster reached the point of being illuminated by the sun than it lost its inner strength and could only use the one that came from the earth. But it could still use it because the oyster was open at the bottom. When this oyster was as large as present-day France, it was open at the bottom and could absorb the earth forces that came from the sun. When these animals had then transformed themselves into megatheriums, into ichthyosaurs, when the sun shone on them from above, and they were no longer open from below, they were dependent on the reproductive power that they had within themselves, which was at most refreshed by the sun.

Yes, gentlemen, there must have been a time when animals acquired reproductive powers that they could not get when the sun shines from outside. There must have been a time when the sun was inside the earth, when not just a little of the sun's energy came into the earth, which remains in the earth in winter, for example, for the potatoes; but there was a time when the whole sun was inside the earth.

Now you will say: But the physicists say that the sun is so terribly hot, and if the sun were inside the earth, it would have burned everything. — Yes, gentlemen, you only know that from the physicists. But the physicists would be extremely astonished if they could see what the sun really looks like. If they could build a balloon and go up there, they would not find that the sun is so hot, but the sun is full of life forces, and it develops heat as the sun's rays pass through air and everything. That's where it develops heat first. So when the sun was once inside the earth, it was full of life forces. It could not only give the little life force that it can give today, but when the sun was once inside the earth, these living beings, animals and plants that were there at the time, could get enough of what the sun gave them, because the sun was inside the earth itself. But then these oysters did not develop any shells either, but were just slime.

And now imagine: there was the Earth, the Moon in it, the Sun was inside the Earth, oysters developed that had no shells, but were slime. Mucus formed; it smeared off, separated, and an oyster formed again, and again an oyster formed, and so on. But they were so huge that they could not be distinguished from each other. They were adjacent to each other. What must the earth have looked like back then? It was similar to our brain, where the cells also lie next to each other. There, too, one cell lies next to the other; only that they die, whereas in the past, when the sun was inside the earth, oyster cells, huge cells, were one next to the other, and the sun developed its powers, which it was constantly developing because it was inside the earth. Yes, gentlemen, now consider this: there was the earth (see drawing), here a giant oyster, there another giant oyster, again one, all such giant slime balls next to each other, and they were always reproducing. And today's oysters reproduce so quickly that they can have a million offspring in a short time; the oysters of that time reproduced even more quickly. Gosh, no sooner had the old oyster arrived than the young were already there, and they had young of their own and so on. The old ones had to dissolve again. If someone had looked at it from the outside, how this huge lump of earth was there like a big brain, of course much softer, much slimier than a brain today, how a giant oyster reproduced so quickly - but each one could have had a million offspring again - he would have seen: everyone had to defend themselves against the others because they bumped into each other. And if someone had come, an especially curious one, and had watched from a foreign star, he would have seen: There below, floating in space, is a giant body, but it is all life, constantly producing life, not just consisting of millions of nested oysters, but constantly reproducing. And what would he have seen? Exactly the same thing – only on a gigantic scale – as can be seen today when a human being's tiny egg is examined in the early stages! There, too, it is only a very small-scale process. There are also these small cell mucus vesicles that multiply rapidly.

166 otherwise the human being would not be able to reach his size in the first few weeks in which he is carried. The cells are so small that they have to multiply very quickly. If you had looked at the earth at that time, you would have seen the image of the earth: a giant animal, and within it the forces of the sun and the moon, in the whole earth inside.

You see, I have now shown you how to go back to the time of the earth's development when the earth, sun and moon were still one body. But, gentlemen, I would like to say: in Faust, if you have read or ever read it, Gretchen, who is sixteen years old, says to Faust when he is explaining his religion: “The pastor also says something like that; but it is a little different.” So you could also say: “Yes, the professors also say something like that, but it is a little different.” You say: “Once the sun was one body with the earth and the moon.” — That's what they say; because they say, isn't it: This sun, it was a giant body; then it turned, and then the earth split off as it turned. Then the earth turned further, and then the moon split off again. —- So basically, they also say that all three were once one body.

Then people come and say: That can be proved; it is already being proved to schoolchildren. It can be demonstrated terribly nicely. You take a small drop of oil – which floats on water – and then you take a sheet of card and cut out a small circle, push a pin through the top; afterwards you put it into the water and turn the head of the pin. The little oltröpfelchen split off and go around like that. There you have it, they say, there you see it: that happened once in the world! There was a huge gas ball in the world, just gas; but the story turned, and it was mobile. And then the outer things were just split off, our earth from the sun, just as these oltröpfchen were split off. They can prove that in school. And the children, who believe in authority, say: It happened quite naturally; there was once a huge ball of gas that was rotating, and that's how the planets were split off. We saw it ourselves, how the droplets were split off.

But now you must also ask the children: Did you see the schoolmaster up there turning the pinhead? So you have to imagine a giant schoolmaster who turned the gas ball at that time, otherwise the planets would not have been able to split off! — The giant schoolmaster - in the Middle Ages he was depicted: that was the Lord God with the long beard. That was the giant schoolmaster, and these people forget him.

But it is no explanation to assume a giant gas ball that rotates, and that could only rotate if a giant world schoolmaster had once existed. That is no explanation. But, gentlemen, it is an explanation when you come to the conclusion that the sun and the moon were connected to the earth and that it moved itself. That could move. A ball of gas cannot move by itself. But what I have explained to you here could move. In those days it did not need a world school master, but it was alive in itself. The Earth was once a living being, and indeed one such as a seed is today, and it contained the Sun and the Moon. The Sun and the Moon emerged from the Earth, leaving their inheritance behind, so that today the germinating power, protected in the maternal and paternal bodies of the human being, these powers, which once could come directly from the Sun, still reproduce and today develop the animals, the seeds and eggs in themselves, carry the ancient solar power in their egg and seminal fluids, carry it within themselves as an inheritance from ancient times, from the times when the earth itself still had the sun and moon within it.

You see, that is a real explanation, and only if you understand it that way can you really understand. Then you realize that there was once a time when the moon flew out and the earth flew out of the sun with the moon. We will discuss this matter further next Saturday at nine o'clock. It will still be a bit difficult, but nevertheless I believe that history looks like this so that you can understand it.

IX. Früheste Erdenzeit

Ich habe Ihnen das letzte Mal geredet von dem Herausfliegen des Mondes aus der Erde und wie das mit dem Leben auf der Erde überhaupt zusammenhängt. Ich kann mir schon denken, daß Sie viele Fragen haben werden. Wir können sie dann am nächsten Samstag behandeln. Überlegen Sie sich bis dahin einiges. Aber heute muß ich noch einiges auseinandersetzen. Da können sich auch vielleicht einige Fragen ergeben.

Wir haben gesagt: Solange der Mond innerhalb der Erde war, solange war es mit dem, was man Fortpflanzungskraft der tierischen Wesen nennen kann, etwas ganz anderes als später, nachdem der Mond hinausgeflogen war. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß in der Zeit, in der der Mond noch in der Erde war, der Mond diejenigen Kräfte für die Erde hergegeben hat, die gewissermaßen die mütterlichen Kräfte sind, die weiblichen Kräfte. So daß wir uns vorstellen können: Es hat eine Zeit gegeben, da war der Mond noch in der Erde drinnen. Ich will Ihnen das nur ganz schematisch aufzeichnen, wie das war.

Als der Mond noch in der Erde drinnen war, da war er nicht in der Mitte drinnen, sondern etwas nach außen gelegen (siehe Zeichnung, links). Wenn Sie heute die Erde anschauen, dann werden Sie ja auch bemerken, daß auf der einen Seite, mehr dahin, wo Australien liegt, viel Wasser auf der Erde ist, währenddem auf der Seite, wo Europa liegt und Asien, viel Land ist. So daß die Erde eigentlich nicht Land und Wasser gleich verteilt hat, sondern die Erde ist so, daß sie auf der einen Seite eigentlich das meiste Land hat undauf der anderen Seite das meiste Wasser. Also gleich verteilt ist der Stoff auf der Erde nicht (siehe Zeichnung $.149, rechts). Das war auch nicht gleich verteilt, als der Mond noch in der Erde drinnen war. Der Mond war eben nach der Seite gelegen, wo die Erde überhaupt die Neigung hat, schwer zu sein. Natürlich, wenn da ein fester Stoff liegt, ist sie dort schwer. So daß ich also die Sache so zeichnen muß, wie ich es dort mit weißer Kreide bezeichnet habe.

Nun müssen Sie sich aber vorstellen, daß damals die Befruchtung so vor sich gegangen ist, daß der Mond, der in der Erde war, diesen Riesenviechern die Kräfte gegeben hat, durch die sie gewissermaßen Fortpflanzungsstoff lieferten. Man kann nicht sagen, daß dazumal schon etwa die Tiere richtige Eier gelegt hätten. Diese Riesenaustern sind ja selber eigentlich nur eine schleimige Masse gewesen und sie haben eben ein Stückchen von sich abgesondert. So daß solch eine riesige Auster, wie ich es Ihnen das letzte Mal beschrieben habe, die ursprünglich so groß gewesen sein könnte wie ganz Frankreich, da eine mächtige Schale gehabt hat, auf der man hätte herumspazieren können, und gegen das Innere der Erde zu eine Schleimmasse. Auf diese Schleimmasse haben die Mondenkräfte gewirkt, und da hat sich ein Stückchen Schleimmasse abgesondert. Das ist dann weitergeschwommen in der Erde. Und wenn wiederum die Sonne daraufgeschienen hat - ich habe Ihnen das an dem Beispiel vom Hund anschaulich erklärt —, hat sich eben eine Eischale gebildet, und dadurch, daß sich diese Eischale gebildet hat, wurde die schleimige Masse der Auster wiederum geneigt, ein Stückchen von sich abzusondern, und dann konnte ein neues Tier entstehen. So daß also die weiblichen Kräfte vom Mond kamen, der in der Erde war, und die männlichen Kräfte von der Sonne, die von außen auf die Erde draufschien. Nun, meine Herren, da schildere ich Ihnen eine ganz bestimmte Zeit, die Zeit eben, wo der Mond noch in der Erde drinnen war.

Nun müßten Sie sich folgendes vorstellen. Heute, wo der Mond draußen ist, außerhalb der Erde, da wirkt er ganz anders. Sie wissen ja auch, wenn die Kohlensäure im Menschen drinnen ist - ich habe es Ihnen das letzte Mal gesagt —, wirkt sie ganz anders, als wenn sie draußen ist, wo sie ein Gift ist. Wenn Sie sich an die Fortpflanzung der Tiere heute erinnern, so müssen Sie sagen: Die Tiere müssen Eier hervorbringen, und diese Eier müssen dann erst in irgendeiner Weise befruchtet werden. Dasjenige also, was früher der Mond gegeben hat, als er drinnen war in der Erde, das haben jetzt die Tiere in sich. Die Tiere haben diese Mondenkräfte in sich.

Und von außen gibt ja der Mond auch noch Kräfte. Ich habe Ihnen das letzte Mal gesagt: Sogar die Dichter wissen das, daß der Mond der Erde Kräfte gibt. Aber das sind Kräfte, durch die die Phantasie angeregt wird, durch die man innerlich lebendiger wird. Das sind Kräfte, die nicht mehr auf die Fortpflanzung wirken, sondern die von außen hereinstrahlen, die gar nicht mehr die Fortpflanzung bewirken können.

So müssen Sie sich vorstellen: Dasjenige, was der Mond der Erde geben konnte, als er noch drinnen war, diese Fortpflanzungskräfte, die haben sich die Tiere angeeignet, als Erbschaft bekommen, und die pflanzen sie jetzt fort von einem Tier aufs andere. Also wenn Sie die Eier der Tiere anschauen, so müssen Sie sich sagen: Da drinnen sind die Mondenkräfte. Aber diejenigen Mondenkräfte sind da noch drinnen, welche gewirkt haben, als der Mond noch in der Erde war. Heute kann der Mond nicht mehr viel anderes bewirken, als daß er den Kopf anregt. Also der Mond wirkt heute auf den Kopf. Dazumal hat er aber gerade auf die Fortpflanzung gewirkt. Sehen Sie, das ist ein beträchtlicher Unterschied. Es ist ein großer Unterschied, ob irgend etwas in der Erde drinnen ist, oder ob es außerhalb der Erde ist.

Mit der Fortpflanzung ist es ja eben doch eine recht merkwürdige Sache. Aber wiederum müssen wir sagen: Alles Verständnis der Natur überhaupt hängt zusammen damit, daß man die Fortpflanzung versteht. Denn dadurch entstehen heute noch die einzelnen Tiere und die einzelnen Pflanzen. Wenn die Fortpflanzung nicht wäre, wäre alles längst tot geworden. Man muß schon, wenn man irgend etwas über die Natur verstehen will, die Fortpflanzung verstehen. Aber mit der Fortpflanzung ist es etwas Eigentümliches auf der Erde.

Denken Sie sich einmal: Der Elefant hat die Eigentümlichkeit, daß er erst mit etwa fünfzehn, sechzehn Jahren imstande ist, ein einziges Junges hervorzubringen. Nehmen Sie dagegen eine Auster; das ist so ein kleines, schleimiges Tier. Wenn Sie sich dieses riesig groß denken, so haben Sie ungefähr diejenigen Viecher, die ich Ihnen für die damalige Zeit gezeigt habe. Also, an der Auster kann man schon etwas lernen. Aber die Auster ist nicht wie der Elefant, der so viele Jahre warten muß, um ein Junges hervorzubringen. Eine einzige Auster kann in einem Jahr eine Million Austern hervorbringen. Also eine Auster steht in einem anderen Verhältnis zu der Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit als der Elefant.

Nun, meine Herren, ein anderes interessantes Tier ist die Blattlaus. Sie wissen, sie kommt auf den Blättern der Bäume vor, findet sich überhaupt als eine recht schädliche Bevölkerung der Pflanzenwelt. Man leidet sehr unter ihr. Eine Blattlaus ist ja, wie Sie wissen, viel kleiner als ein Elefant, aber sie kann in wenigen Wochen - eine einzige Blattlaus! — mehrere tausend Millionen Nachkommen erzeugen. Also ein Elefant braucht etwa fünfzehn, sechzehn Jahre, bis er imstande ist, einen einzigen Nachkommen hervorzubringen, und die Blattlaus, die kann eben in wenigen Wochen sich so vermehren, daß von einer einzigen mehrere Millionen kommen.

Und dann gibt es noch kleinwinzige Tiere, die nennt man Vorticellen. Wenn man sie durch ein Mikroskop anschaut, dann sind sie überhaupt nur so ein ganz kleines Schleimklümpchen, und sie haben einen Faden, an dem sie sich fortschlängeln. Es sind ganz interessante Tiere, aber sie bestehen nur aus einem ganz kleinen Schleimklümpchen, wie wenn man einen Faden aus einer Auster herausnehmen würde, und sie schwimmen so herum. Diese kleinen Vorticellen, die sind nun ganz so, daß sie in vier Tagen hundertvierzig Billionen Nachkommen — eine einzige! — erzeugen können. Also man kann es auf die Tafel gar nicht aufschreiben, so viele Nullen muß man aufschreiben. Das einzige, was damit konkurrieren kann, ist jetzt die russische Valuta!

Also Sie sehen, es ist ein beträchtlicher Unterschied in der Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit zwischen einem Elefanten, der fünfzehn, sechzehn Jahre warten muß, um ein einziges Junges hervorzubringen, und solch einer kleinen Vorticelle, die in vier Tagen sich so vermehrt, daß hundertvierzig Billionen Nachkommen wachsen.

Also sehen Sie, da liegen wirklich ganz bedeutende Naturgeheimnisse vor. Und es gibt eine ganz interessante französische Erzählung, die äußerlich mit dem nicht viel zu tun hat, aber innerlich doch. Da war ein bedeutender französischer Dichter — der hieß Racine. Und dieser Racine, der brauchte, um solch eine Dichtung, wie zum Beispiel die «Athalie» zu schreiben, sieben Jahre. Also er hat in sieben Jahren ein solches Theaterstück wie die «Athalie» geschrieben. Und da gab es zu seiner Zeit einen anderen Dichter, der war furchtbar stolz gegen den Racine und sagte: Der Racine braucht sieben Jahre, um ein Stück zu schreiben; ich schreibe in einem Jahr sieben Stücke! - Und da entstand eine Fabel, so eine Erzählung, und diese Erzählung, diese Fabel lautet: Es haben einmal gestritten dasSchwein und der Löwe; und dasSchwein, das stolz war, sagte zum Löwen: Ich kriege jedes Jahr sieben Junge, aber du, Löwe, du bringst nur ein einziges in einem Jahr zustande. — Da sagte der Löwe: Jawohl, aber das einzige, das ist eben auch ein Löwe, und deine sieben sind Schweine. - Und damit, nicht wahr, hat Racine den Dichter abfertigen wollen. Er hat ihm nicht gerade sagen wollen, seine Theaterstücke seien Schweine, aber er verglich das, denn er sagte: Nun ja, du machst alle Jahr sieben solche Stücke, aber ich mache in sieben Jahren eine «Athalie» — die heute weltberühmt ist.

Sehen Sie, so kann man sagen: Selbst in einer solchen Fabel, in einer solchen Erzählung liegt so etwas drinnen, daß es wertvoller ist, nach Elefantenart fünfzehn, sechzehn Jahre zu brauchen, um dann ein Junges zu kriegen, als eine Vorticelle zu sein, die in vier Tagen sich so vermehrt, daß sie hundertvierzig Billionen Junge kriegt. Man redet schon viel, daß die Kaninchen so viel Junge kriegen; wenn man nun gar von der Vorticelle reden würde - eine solche Vermehrungsfähigkeit ist ja gar nicht auszudenken!

Nun muß man doch herausbekommen, woran das liegt, daß solche kleinwinzigen Tiere so viele Junge kriegen, während der Elefant so lange dazu braucht.

Nun habe ich Ihnen gesagt: Die Sonne, die ist dasjenige, was eigentlich der Befruchtung zugrunde liegt. Die Sonne braucht man also heute auch noch bei der Befruchtung. Und ich habe Ihnen auch gesagt: Wenn ein Himmelskörper draußen ist wie der Mond, so wirkt er höchstens noch auf den Kopf, aber nicht mehr wirkt er auf die Unterleibsorgane, also nicht mehr direkt auf die Fortpflanzungskräfte. Die Fortpflanzungskräfte müssen heute vererbt werden von einem Wesen aufs andere. Aber, meine Herren, in einem gewissen Sinne ist dennoch dasjenige, was da geschieht in der heutigen Fortpflanzung noch, doch noch vom Monde abhängig. Und das will ich Ihnen auf die folgende Weise erklären, indem ich auch wiederum auf die Sonne zurückgehe.

Sehen Sie, wir müssen uns fragen: Warum braucht der Elefant fünfzehn, sechzehn Jahre, um seine Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit so weit zu bringen, daß er ein Junges kriegt? Nun wissen Sie alle, daß der Elefant ein Dickhäuter ist, und weil er ein Dickhäuter ist, braucht er so lange. Eine dicke Haut läßt nämlich die Sonnenkräfte weniger stark durch sich durch, als wenn man eine Blattlaus ist und ganz weich ist und überall die Sonnenkräfte hereinkönnen. So daß tatsächlich die geringe Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit des Elefanten eben mit seiner Dickhäutigkeit zusammenhängt.

Das können Sie ja auch daran schen: Denken Sie wiederum zurück an diese riesigen schwimmenden Austern. Ja, es würde niemals eine zweite Auster entstehen, wenn es auf die Sonne nur ankäme, die da draufstrahlt auf diesen Schuppenpanzer, auf die dicke Haut! Sondern diese Auster, die gibt ein bißchen Schleim ab, habe ich Ihnen gesagt; der Schleim, der hat noch keine Austernschale, da kann dieSonne draufkommen. Und indem sie anfängt, den Schleim abzutrocknen und eine neue Auster dadurch entstehen kann, wirkt sie auf diese Auster befruchtend. — Ja, wenn die Sonnenstrahlen von außen kommen, meine Herren, dann können sie eben nur Schalen erzeugen. Wie kommt es denn, daß die Sonnenkräfte dennoch befruchtend wirken können?

Sehen Sie, da müssen wir wiederum etwas anderes anschauen, damit Sie einsehen können, wie die Geschichte eigentlich zusammenhängt. Sie wissen vielleicht, daß die Bauern, wenn sie die Kartoffeln geerntet haben, ziemlich tiefe Gruben machen, und in diese Gruben hinein legen sie die Kartoffeln. Dann graben sie die Gruben wieder zu. Und sie graben dann später, wenn der Winter vorüber ist, aus diesen Gruben die Kartoffeln wiederum aus, weil sie da drinnen gut geblieben sind. Wenn sie die Kartoffeln einfach in dem Keller aufgehoben hätten, wären sie zugrunde gegangen. Da drinnen bleiben sie ganz gut.

Woher kommt das eigentlich? Es ist eine sehr interessante Sache. Die Bauern wissen nicht viel Auskunft darüber zu geben. Aber, meine Herren, wenn Sie selber eine Kartoffel wären und würden da hineingegraben in diese Grube, so würden Sie sich da drinnen, wenn Sie nicht gerade etwas zu essen brauchten, eigentlich außerordentlich gut fühlen. Denn sehen Sie, da drinnen bleibt nämlich die Sonnenwärme vom Sommer drinnen, und dasjenige, was im Sommer von der Sonne auf die Erde draufscheint, das zieht sich immer mehr und mehr eben nach unten hin. Und wenn man im Januar in die Erde hineingräbt, so ist da noch die Sonnenwärme und alle anderen Sonnenkräfte vom Sommer, die sind da eineinhalb Meter tief noch drinnen.

Das ist das Merkwürdige. Im Sommer, da ist die Sonne draußen, da erwärmt sie von draußen, und im Winter, da zieht sich die Sonnenkraft nach unten und ist weiter unten zu finden. Aber sie kann nicht sehr tief nach unten gehen; sie strömt wiederum zurück. Wenn man eine Kartoffel wäre und da unten läge, so würde es einem ganz gut gehen; einheizen brauchte man nicht, denn erstens ist da noch die Wärme vom Sommer drinnen, und zweitens kommt es ganz warm herauf von unten, weil die Sonnenkräfte wiederum zurückstrahlen. Und diesen Kartoffeln ist es eigentlich furchtbar wohl. Da genießen sie eigentlich erst die Sonne. Im Sommer haben sie nicht viel von der Sonne, da ist es ihnen sogar unangenehm. Wenn sie Köpfe hätten, kriegten sie Kopfweh, wenn die Sonne so draufscheint; da ist es eigentlich unangenehm für die Kartoffeln. Aber im Winter, wenn ihnen die Wohltat geschieht, in die Erde hineingegraben zu werden, da können sie die Sonne erst so recht genießen.

Daraus sehen Sie, daß die Sonne ja nicht nur wirkt, wenn sie auf etwas draufscheint, sondern sie wirkt weiter, wenn ihre Kräfte von etwas aufgefangen, aufgehalten werden.

Ja, meine Herren, jetzt tritt eine Eigentümlichkeit ein. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt: Wenn ein Körper draußen ist aus der Erde, dann wirkt er abtötend, entweder — wie die Kohlensäure - wie ein Gift, oder aber wie die Sonne hier, die Schuppen erzeugt, wenn sie draufscheint; die verhärtet das Lebewesen, auf das sie draufscheint. Aber im Winter, da istes ja gar nicht wahr, daß die Sonne von außen wirkt; da wirkt sie vom Inneren der Erde. Da läßt sie ihre Kraft zurück, wirkt im Inneren der Erde. Und da frischt sie im Inneren der Erde auch wiederum die Fortpflanzungskräfte auf.So daß die Fortpflanzungskräfte heute, in unserer Gegenwart, auch von der Sonne kommen, aber nicht etwa von der direkten Sonnenbestrahlung, sondern sie kommen von dem, was in der Erde drinnen zurückbleibt und im Winter dann wiederum zurückstrahlt,

Es ist eine sehr interessante Sache. Es ist gerade so, wie wenn wir die Kohlensäure einatmen: da ist sie ein Gift. Wenn aber die Kohlensäure in unserem Körper drinnen ist und durch das Blut geht, da brauchen wir sie. Denn hätten wir keinen Kohlenstoff, so hätten wir überhaupt nichts in uns. Da brauchen wir ihn im Inneren, da ist er wohltätig; von außen ist er Gift. Sonnenstrahlen von außen erzeugen Schalen bei den Tieren, Sonnenstrahlen, von innen aufgefangen und wiederum zurückgestrahlt, erzeugen Leben, machen die Tiere fortpflanzungsfähig.

Aber, meine Herren, denken Sie sich jetzt, Sie wären nicht eine Kartoffel, sondern ein Elefant. Da hätten Sie eine furchtbar dicke Haut, und da ließen Sie nur wenig von dieser Wärme in sich herein, die die Erde da von der Sonne hat. Daher brauchten Sie furchtbar lang, wenn Sie ein Elefant wären, um ein Elefantenkind hervorzubringen. Aber denken Sie sich, Sie wären eine Blattlaus oder eine Auster; da wären Sie ja -— bei dieser Auster — gerade gegen die Erde zu nur eine Schleimmasse. Solch eine Schleimmasse ist der Elefant nicht. Der Elefant ist nach allen Seiten durch seine Haut abgeschlossen, läßt also diese Wärme, die von unten kommt, furchtbar langsam nur in sich hinein.

Nun, sehen Sie, das ist so: Solche Tiere wie Blattläuse, die halten sich auch so in der Nähe der Erde schon auf und außerdem an Pflanzen und haben gar keine dicken Häute; die können furchtbar leicht das, was da von der Erde zurückdunstet, mit dem Frühling aufnehmen, bekommen also ihre Fortpflanzungskräfte immer rasch aufgefrischt. Und die Vorticellen erst recht, denn die leben im Wasser und das Wasser bewahrt die Sonnenwärme noch viel intensiver, so daß die aufgesparte Sonnenwärme in den Vorticellen die hundertvierzig Billionen zur richtigen Jahreszeit hervorbringt; das heißt, wenn sie genügend aufgenommen haben von dem, was die Sonnenwärme im Wasser ist, können sie sich furchtbar rasch fortpflanzen. So können wir sagen: Heute ist es bei der Erde so, daß sie die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit ihren Wesen dadurch gibt, daß sie die Sonnenkräfte in sich während des Winters bewahrt.

Nun gehen wir von da aus auf die Pflanzen über. Sehen Sie, bei den Pflanzen, da ist es so: Sie wissen, es gibt bei den Pflanzen auch eine Fortpflanzung durch sogenannte Stecklinge. Wenn also die Pflanze aus der Erde herauswächst, so kann man irgendwo einen Steckling abschneiden. Man muß ihn ordentlich herausschneiden, kann ihn dann wiederum einsetzen, und das wächst sich dann zur Pflanze aus. Solch eine Fortpflanzung gibt es bei gewissen Pflanzen. Woher kommt denn das? Diese Kraft, die da die Pflanzen haben, sogar noch durch ein Stückchen von ihnen sich fortzupflanzen, haben die Pflanzen aus dem Grunde, weil sie ja den Samen im Winter in der Erde drinnen haben. Das ist nämlich eine ganz besonders wichtige Sache bei den Pflanzen. Will man irgendwie Pflanzen zum richtigen Wachstum bringen, so ist es ja so, nicht wahr, daß sie eigentlich im Winter in der Erde drinnen sein müssen. Sie müssen überhaupt aus der Erde herauswachsen. Es gibt ja Sommerfrüchte, da könnten wir ja später einmal darüber reden. Aber in der Hauptsache müssen die Pflanzen in der Erde drinnen ihren Samen entwickeln, und dann können sie wachsen. Man kann manchmal zwiebelartige Gewächse auch im Wasser zum Wachsen bringen, aber da muß man besondere Maßregeln ergreifen, nicht wahr. In der Hauptsache ist es so in der Natur, daß die Pflanzen in die Erde hineingesetzt werden müssen und von da aus ihre Kraft zum Wachsen haben müssen.

Was geschieht nun da, meine Herren, wenn ein Samenkorn in die Erde hineingelegt wird? Da ist dieses Samenkorn erst recht in die Wohltat versetzt, diese von der Sonne der Erde übergebenen Kräfte in sich aufzunehmen. Gerade das Pflanzensamenkorn, das nimmt diese Kräfte, die da von der Sonne in die Erde hineinkommen, erst recht auf.

Beim Tier, da geht das viel schwerer. Diejenigen Tiere, die in der Erde selber drinnen sind wie die Regenwürmer und dergleichen, die nehmen diese Kraft auch leicht auf. Deshalb pflanzen sich diese auch alle sehr stark fort, alle die Tiere, die entweder ganz nahe der Erde oder in der Erde sind. Würmer sind ja auch so, daß sie furchtbar viel Nachkommen haben, und zum Beispiel gerade solche Würmer, die auch leider in die menschlichen Gedärme kommen können, erzeugen furchtbar viele Nachkommen, und der Mensch muß fortwährend seine eigenen Kräfte anstrengen, damit diese Würmer nicht schrecklich viele Nachkommen erzeugen. So daß man da eben, wenn man Würmer in sich hat, fast alle Lebenskräfte anwenden muß, um diese Schreckenskerle, die man in sich hat, zu töten.

Ja, aber Pflanzen, die sind in der Lage, daß sie aus dem Boden herauswachsen (siehe Zeichnung); da unten ist die Wurzel, dann wachsen sie aus dem Boden heraus, und dann haben sie die Blätter, dann entwickeln sie die Blüten und neue Samen. Aber, meine Herren, Sie wissen ganz genau: Wenn die Blüte anfängt sich zu entwickeln, da wächst die Pflanze nicht mehr nach oben. Das ist schr interessant. Der Same der Pflanze, der Keim, der wird in den Boden gegeben; da wächst der Stengel heraus, es werden Blätter, grüne Blätter, und nachher kommt die Blüte. Da wird das Wachstum aufgehalten, und die Pflanze macht jetzt geschwind, erzeugt geschwind den Samen. Denn würde sie nicht geschwind den Samen erzeugen, so würde die Sonne alle Kraft auf diese Blütenblätter verwenden, die unfruchtbar wären. Die Pflanze würde oben eine riesige schöne Blüte kriegen, vielfarben, aber der Same würde sich nicht entwickeln können. Die Pflanze nimmt zuletzt noch alle Kraft zusammen, um geschwind den Samen zu erzeugen.

Sehen Sie, die Sonne, die von außen kommt, die hat die Eigentümlichkeit, die Pflanzen schön zu machen. Wenn wir schöne Pflanzen auf der Wiese finden, so ist es die äußere Sonne mit ihren Strahlen, die diese schönen Farben hervorbringt. Aber sie würde die Pflanzen damit ersterben machen, geradeso wie sie mit der Austernschale die Auster ersterben macht, vertrocknet.

Daher können Sie das auch auf der ganzen Erde sehen. Dieses Wirken der Sonne können Sie besonders schön sehen, wenn Sie in heiße Gegenden kommen, in Äquatorialgegenden; da schwirren alle Vögel in den wunderbarsten Farben durcheinander. Das ist die Wirkung der äußeren Sonne. Diese Federn sind alle wunderschön gefärbt, enthalten aber keine Lebenskraft mehr in sich. In den Federn ist die Lebenskraft am meisten abgestorben.

Und so ist es bei der Pflanze. Wenn sie aus dem Erdboden herauswächst, da hat sie strotzende Lebenskraft. Dann verliert sie diese immer mehr und muß zuletzt noch alle Kraft zusammennehmen; das ganz kleine bißchen Lebenskraft bringt sie noch in den Samen hinein. Und die Sonne macht schöne Blätter, farbige Blüten, aber sie tötet diePflanze dabei ab. In den farbigen Blumenblättern lebt nichts von Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit.

Aber was tut denn die Pflanze, wenn man ihren Samen in die Erde hereingibt? Da läßt sie sich nicht nur darauf ein, in die Erde hineingelegt zu werden, sondern sie bringt Wachstum in den Blättern herauf; das trägt sie herauf. Wenn ich da etwas Grünes zeichne, entwickeln das die Sonnenkräfte, also Wärme, Licht und so weiter. So gehen die Sonnenkräfte herauf in der Pflanze. Die nimmt sich die Pflanze im Samenkorn mit, währenddem die Sonnenkräfte, die von außen kommen, die Pflanze ertöten, so daß da eine sehr schöne Blüte entsteht. Aber da mitten drin ist noch der Same, der noch von der mitten im Winter aufgespeicherten Sonnenwärme kommt. Von der heurigen Sonne kommt der Same nicht. Das ist bloß eine falsche Vorstellung. Von der heurigen Sonne kommt die schöne Blüte; der Same aber kommt von der Sonnenwärme des vorigen Jahres, der hat noch die Kraft, die die Sonne erst der Erde hingegeben hat. Die trägt die Pflanze durch ihren ganzen Körper durch.

Beim Tier ginge das nicht so leicht. Das Tier ist darauf angewiesen, daß diese Sonnenwärme mehr von außen, mehr von der Erde kommt und nur aufgefrischt wird. Denn das Tier nimmt nicht die Sonnenkräfte so direkt auf wie die Pflanze. Die Pflanze aber trägt durch ihren eigenen Leib bis zum Samen in der Blüte herauf die vorjährige Sonnenwärme, die also in die Erde hinein sich aufgespeichert hat.

Wenn man diese Geschichte richtig betrachtet — es ist außerordentlich interessant, es ist wunderbar interessant —, dann sagt man sich: Pflanzen und Tiere pflanzen sich fort. Sie könnten sich nicht fortpflanzen, wenn nicht die Sonne wirkte. Wäre keine Sonne da, könnten sie sich nicht fortpflanzen. Aber die Sonne, die draußen ist am Himmelsraume, außer der Erde, die tötet gerade die Fortpflanzungsfähigkeit. Es ist eine solche Sache wie mit der Kohlensäure: Wenn wir die Kohlensäure einatmen, so tötet sie uns; wenn wir sie in uns haben, so belebt sie uns. Wenn die Erde die Sonnenstrahlen von außen bekommt, so werden ihre Tiere und Pflanzen getötet; wenn die Erde den Tieren und Pflanzen von ihrem Inneren aus das, was in der Sonne ist, geben kann, so werden sie gerade recht belebt und zur Fortpflanzung angeregt. Das sieht man an den Pflanzen; die entwickeln fortpflanzungsfähige Samen nur aus der Kraft der Sonne, die sie von früher mitnehmen, vom vorigen Sommer. Was die Pflanze dieses Jahr schön werden läßt, das kommt von der heurigen Sonne. Das ist überhaupt so: Das Innere, das wächst von der Vergangenheit, und schön - schön wird man durch die Gegenwart,

Nun, meine Herren, dem Elefanten mit seiner dicken Haut, dem würde aber das bißchen Wärme von der Erde her und das bißchen Sonne drinnen, das er von der Erde her bekommt, furchtbar wenig nützen, denn der ist eben ein Dickhäuter. Da gehen diese Kräfte nicht so leicht durch. Der muß sehr viel in seinem eigenen Samen aufgespeichert haben von früher her. Mondenkräfte hat er aufgespeichert. Die braucht er ja natürlich zur mütterlichen, zur weiblichen Fortpflanzung. Die hat er aufgespeichert. Der Mond ist heraus aus der Erde, und die Tiere, die sich fortpflanzen, die haben eben jetzt die Mondenkräfte in sich.

Sehen Sie, da kommt etwas, was man überhaupt recht berücksichtigen muß. Es könnte natürlich einer kommen und sagen: Da ist solch ein dummer Kerl, der von den ehemaligen, von den früheren Mondenkräften sagt, da leben in den Eiern, in den Fortpflanzungskräften noch solche alten Kräfte drinnen. Dieser dumme Kerl behauptet, die gegenwärtigen Fortpflanzungskräfte, die seien von früher her. — Ich würde diesem Menschen einfach sagen: Hast du denn noch nie gesehen, daß etwas, was jetzt lebt, etwas in sich hat, was von früher her ist? — Ich würde ihm einen Buben zeigen, der seinem Vater so ähnlich ist, daß er ihm, wie man sagt, wie aus dem Gesicht geschnitten ist. Ja, wenn man dann zurückgeht — der Vater könnte ja sogar schon gestorben sein; einer könnte den Vater gekannt haben, als der Vater selber ein so kleiner Bub war, wie der Junge jetzt ist, und der Betreffende könnte sagen: Ja, der Bub ist seinem Vater wie aus dem Gesicht geschnitten. — Aber er schaut ihm gerade ähnlich, so wie der Vater war, als er selber so ein kleiner Bub war. Was Sie da vor vielleicht dreißig oder vierzig Jahren gesehen haben — bei dem kleinen Bub ist es jetzt noch drinnen! Immer sind die Kräfte der Vergangenheit in dem, was in der Gegenwart lebt, noch drinnen. Und so ist es auch mit den Fortpflanzungskräften. Das, was in der Gegenwart ist, das stammt aus der Vergangenheit.

Sie wissen ja, man hat es als einen besonders starken Aberglauben angeschaut, daß der Mond aufs Wetter wirken soll. Nun, darinnen steckt auch sehr viel Aberglaube. Aber einmal hat es doch zwei Gelehrte gegeben in Deutschland, an der Universität in Leipzig, von denen hat der eine sich gesagt — Fechner hat er geheißen -: Vielleicht steckt in diesem Aberglauben, daß der Mond aufs Wetter wirke, wirklich ein bißchen Wahrheit. - Und da hat er sich notiert, wie das Wetter war beim Vollmond, und wie das Wetter war beim Neumond, und hat gefunden: Es ist ein Unterschied; es regnet mehr bei Vollmond als bei Neumond. — Das hat er herausgekriegt. Daran muß man ja noch nicht glauben. Solche Notizen sind nicht sehr überzeugend. Bei der wirklichen Wissenschaft muß man viel, viel genauer arbeiten. Aber er hat doch gesagt, man müsse eben solche Untersuchungen fortsetzen und sehen, ob nicht doch dabei herauskommt, daß der Mond auf das Wetter wirkt.

Nun war an derselben Universität Leipzig ein anderer, einer, der sich für viel gescheiter gehalten hat — Schleiden hat er geheißen -, der hat gesagt: Nun fangen sogar schon meine Kollegen an, davon zu reden, daß der Mond auf das Wetter wirkt. Donnerwetter, die Geschichte geht nicht, da muß man mit aller Kraft dagegen anstürmen! — Da hat der Fechner gesagt: Nun schön, zwischen uns Männern wird der Streit schon bestehen bleiben, aber wir haben ja auch Frauen. — Sehen Sie, das war noch in früheren Zeiten. Als die zwei Universitätsprofessoren in Leipzig gelebt haben, da haben die Universitätsprofessoren-Frauen noch einen alten Brauch gehabt in der Stadt. Sie haben nämlich ihre Tröge, ihre Bottiche in den Regen gestellt, um da Waschwasser zu bekommen. Sie haben das gesammelt, weil das Wasser nicht so leicht zu kriegen war im alten Leipzig. Es hat dazumal noch keine Wasserleitungen gegeben. - Da hat der Professor Fechner gesagt: Ja, diesen Streit sollen einmal unsere Frauen ausmachen. Die Frau Professor Schleiden und die Frau Professor Fechner, die sollen das so machen: Damit sie immer gleich viel Regenwasser bekommen, kann Frau Professor Schleiden beim Neumond ihre Tröge herausstellen, und meine Frau, die stellt die Tröge heraus beim Vollmond! — Da hat er sich gesagt: Nach meiner Rechnung kriegt sie dann das meiste Regenwasser.

Nun, sehen Sie, die Frauen sind nicht darauf eingegangen. Die wollten nicht auf die Wissenschaft ihrer Männer eingehen. Die haben sich gar nicht überzeugen lassen. So kam einmal auf eine merkwürdige Weise die Geschichte heraus, daß ein Mensch, selbst wenn die Wissenschaft in Form vom Mann dasteht, nicht daran glaubt, wie die Frau Schleiden, und sich nicht sagt: Ich kriege geradesoviel Wasser beim Neumond wie beim Vollmond, sondern ihre Regentröge auch beim Vollmond herausstellen wollte, trotzdem ihr Mann fürchterlich gewettert hat auf den Fechner.

Das ist etwas, was ja noch nichts beweist. Aber sehen Sie, etwas Merkwürdiges ist doch, daß heute noch Ebbe und Flut mit Sonne und Mond zusammenhängen. So daß man schon sagen kann: Fluten treten bei einem Mondesviertel ganz anders auf als bei irgendeinem anderen Mondesviertel. Das hängt zusammen. Aber, meine Herren, davon kommt es nicht, daß der Mond irgendwo aufs Meer scheint und dadurch eben Flut entsteht, sondern das ist eine alte Geschichte.

Als der Mond noch in der Erde drinnen war, da hat er seine Kräfte entwickelt und die Fluten bewirkt. Und die Erde hat noch immer diese Reste von den Kräften selbst, durch die die Flut entsteht. Kein Wunder, die Erde macht das schon selbständig. Heute ist es ein Aberglaube, wenn man glaubt, der Mond wirke auf die Erde. Aber er hat einmal auf die Erde gewirkt, als er noch drinnen war, als alles noch auf die Erde gewirkt hat; und die Erde ist noch immer in diesem Zusammenhang drinnen. Sie macht deshalb Ebbe und Flut vom Monde abhängig. Aber das ist nur scheinbar. Geradeso wie wenn ich auf meine Uhr schaue, ich auch nicht sage: Sie wirft mich um zehn Uhr zum Saal heraus. — So treffen heute die Mondphasen mit Ebbe und Flut zusammen, weil das einmal voneinander abhing.

Und so ist es mit den Fortpflanzungskräften, soweit sie vom Mond abhängen, soweit sie also weiblich sind. Und so ist es mit den Fortpflanzungskräften, soweit sie von der Sonne abhängig sind, also von derjenigen Sonnenkraft kommen, die im Inneren der Erde ist.

Aber alle die Tiere, die sich so stark fortpflanzen, bis in die Billionen hinein, die also diese von der Sonne durch die Erde aufgespeicherten Sonnenkräfte benützen können, das sind niedere Tiere. Die höheren Tiere und dieMenschen, die haben diese Fortpflanzungskräfte geschützt im Inneren. Da kommt zwar etwas noch von der Sonnenkraft heran und frischt diese Kräfte immerfort auf. Ohne Auffrischung würden sie auch nicht da sein. Aber aus dem, was heute in der Erde von der Sonnenkraft drinnen ist, würden sie nicht so richtig ihre Fortpflanzungskräfte haben können.

Die Pflanze kann sie haben, weil sie das, was in der Erde drinnen lebt, vom Winter in den Sommer hinein durch ihren eigenen Körper hinaufträgt, Die Pflanze, die hat die Fortpflanzungskraft vom vorigen Jahr.

Aber der Elefant kann sie nicht haben vom vorigen Jahr. Der hat sie von einer Zeit vor Jahrmillionen, und hat sie eben in seinem Fortpflanzungssamen, den er wiederum vererbt vom Elefantenvater auf den Elefantensohn. Da hat er sie drinnen. Aber aus welcher Zeit hat er sie drinnen! Nun, geradeso wie die Pflanze in sich die Fortpflanzungskraft vom vorigen Jahr hat, so hat der Elefant die Fortpflanzungskraft von Jahrmillionen in sich. Deshalb kann sich die Pflanze-und die niedrigen Tiere — daraus fortpflanzen, weil sie heute noch die von der Erde aufgespeicherte Kraft benützen können. Das sind ungeheuer starke Fortpflanzungskräfte. Diejenigen Tiere, die darauf angewiesen sind, sehr weit zurückliegende Kräfte in sich noch aufzubewahren, die können sich nur schwach fortpflanzen.

Aber gehen wir jetzt zurück zu der Zeit, wo da solche Riesenaustern waren: Kaum hat eine solche Auster das erreicht, daß sie von der Sonne beschienen worden ist, da verlor sie schon die innere Kraft, konnte nur diejenige benützen, die aus der Erde heraufkam. Aber sie konnte sie doch noch benützen, weil die Auster nach unten offen war. Wenn diese Auster auch so groß war wie heute Frankreich, nach unten war sie offen, konnte die Erdenkräfte, die von der Sonne kamen, in sich aufnehmen. Als diese Tiere sich dann umgestaltet hatten zu Megatherien, zu Ichthyosauriern, als sie von der Sonne so beschienen wurden, daß sie von allen Seiten kam, sie also nicht mehr von unten her offen waren, da waren sie auf die Fortpflanzungskraft angewiesen, die sie in sich selber hatten, die höchstens aufgefrischt wurde durch die Sonne.

Ja, meine Herren, was muß es denn da einmal für eine Zeit gegeben haben, wenn Tiere Fortpflanzungskräfte gekriegt haben, die sie nicht bekommen können, wenn die Sonne von außen scheint? Es muß einmal eine Zeit gegeben haben, wo die Sonne in der Erde drinnen war, wo also nicht bloß das bißchen Sonnenkräfte in die Erde hereingekommen ist, das im Winter zum Beispiel dableibt für die Kartoffeln; sondern es hat einmal eine Zeit gegeben, wo die ganze Sonne in der Erde drinnen war.

Nun werden Sie sagen: Die Physiker sagen aber, daß die Sonne so furchtbar heiß ist, und wenn die Sonne in der Erde drinnen war, so hätte sie ja alles verbrannt. — Ja, meine Herren, das wissen Sie ja nur von den Physikern. Aber die Physiker würden nämlich höchst erstaunt sein, wenn sie sehen könnten, wie die Sonne wirklich ausschaut. Wenn sie einmal einen Luftballon bauen und da hinauffahren könnten, so würden sie gar nicht finden, daß die Sonne so heiß ist, sondern die Sonne ist gerade in sich drinnen voller Lebenskräfte, und die Hitze entwickelt sie, indem die Sonnenstrahlen durch Luft und alles mögliche durchgehen. Da entwickelt sie erst die Hitze. Also als die Sonne einmal in der Erde drinnen war, da war sie voller Lebenskräfte. Da hat sie nicht nur das bißchen Lebenskräfte geben können, das sie heute geben kann, sondern als die Sonne einmal in der Erde drinnen war, da konnten diese lebendigen Wesen, Tiere und Pflanzen, die damals da waren, genügend kriegen von dem, was ihnen die Sonne gab, denn die Sonne war ja in der Erde selber drinnen. Da entwickelten diese Austern aber auch keine Schalen, sondern da waren sie überhaupt bloßer Schleim.

Und nun denken Sie sich: Da war also die Erde, der Mond in ihr, die Sonne war in der Erde drinnen, Austern entwickelten sich, die keine Schalen hatten, sondern die Schleim waren. Es entstand Schleim; der schmierte sich ab, trennte sich ab, wiederum entstand eine Auster, wiederum entstand eine Auster und so weiter fort. Die waren aber so riesengroß, daß man sie gar nicht voneinander unterscheiden konnte. Sie grenzten aneinander an. Wie muß denn dazumal die Erde ausgesehen haben? So ähnlich wie unser Gehirn nämlich, wo auch die Zellen nebeneinander liegen. Da liegt auch eine Zelle neben der anderen; nur sterben die ab, während dazumal, als die Sonne in der Erde drinnen war, Austernzellen, riesige Zellen, eine neben der anderen, waren, und die Sonne ihre Kräfte entwickelte, die sie ja fortwährend entwickelte, weil sie in der Erde drinnen war. Ja, meine Herren, bedenken Sie jetzt das: Da war also die Erde da (siehe Zeichnung), hier eine Riesenauster, da wieder eine Riesenauster, wieder eine, lauter solche Riesenschleimbatzen nebeneinander, und die pflanzten sich immer fort. Und die heutigen Austern pflanzen sich noch so rasch fort, daß sie in einer kurzen Zeit eine Million Nachkommen haben können; da pflanzten sich die damaligen Austern erst recht rasch fort. Donnerwetter, kaum war die alte Auster da, waren schon die Jungen wieder da, und die hatten wieder Junge und so weiter. Die Alten mußten sich wieder auflösen. Wenn das einer von außen angeschaut hätte, wie da dieser riesige Erdklumpen wie ein großes Gehirn dagewesen wäre, natürlich viel weicher, viel schleimiger als ein heutiges Gehirn, wie da eine Riesenauster sich so schnell fortpflanzte - aber jede andere hätte wieder eine Million Nachkommen haben können -, der hätte gesehen: Da mußte jeder sich gegen die anderen verteidigen, weil sie aneinander anstießen. Und wenn da einer gekommen wäre, ein besonders Neugieriger, und hätte von einem fremden Stern zugeschaut, da hätte er gesehen: Da unten schwimmt im Weltenraum ein Riesenkörper, aber der ist ganz Leben, bringt fortwährend Leben hervor, besteht nicht nur aus Millionen von ineinandergeschobenen Austern, sondern die vermehren sich fortwährend. Und was hätte er gesehen? Ganz dasselbe — nur riesengroß -, was man heute sieht, wenn man ein kleines Ei, aus dem ein Mensch entsteht, in der ersten Zeit anschaut! Da geht es nur ganz kleinwinzig vor sich. Da sind auch diese kleinen Zellenschleimbläschen, die sich rasch vermehren,

166 denn sonst würde der Mensch in den ersten Wochen, in denen er getragen wird, seine Größe nicht erreichen können. Die Zellen sind eben so klein, daß sie sehr rasch sich vermehren müssen. Hätte man dazumal die Erde angeschaut, man hätte das Bild von der Erde bekommen: Ein Riesentier, und darinnen die Kräfte der Sonne und des Mondes, in der ganzen Erde inwendig.

Sehen Sie, jetzt habe ich Ihnen gezeigt, wie man zurückkommen kann zu der Zeit der Erdenentwickelung, wo Erde, Sonne und Mond noch ein Körper waren. Aber, meine Herren, ich möchte sagen: Im «Faust», wenn Sie den einmal lesen oder gelesen haben, da sagt einmal das sechzehnjährige Gretchen, als ihm der Faust seine Religion entwickelt: So ungefähr sagt es der Pfarrer auch; aber doch ein bißchen anders. - So könnten Sie auch sagen: Ja, so ungefähr sagen es einem die Professoren auch, aber doch ein bißchen anders. Sie sagen: Einmal war die Sonne mit Erde und Mond ein Körper. — Das sagen sie schon; denn sie sagen, nicht wahr: Diese Sonne, die war ein Riesenkörper; dann hat sie sich gedreht, und dann hat sich die Erde abgespalten, als sie sich gedreht hat. Dann hat sich die Erde weiter gedreht, und da hat sich wieder der Mond abgespalten. —- Also im Grunde genommen sagt man auch da, es waren alle drei einmal ein Körper.

Da kommen dann die Leute und sagen: Das kann man ja beweisen; den Schulkindern wird das schon bewiesen. Man kann das furchtbar nett vormachen. Man nimmt ein kleines Öltröpfchen — das schwimmt nämlich auf dem Wasser - und dann nimmt man ein Kartenblatt und schneidet einen kleinen Kreis heraus, schiebt oben eine Stecknadel durch; nachher gibt man das ins Wasser und dreht da am Kopf der Stecknadel. Die kleinen Oltröpfelchen spalten sich ab und gehen so herum. Da habt ihr es ja, sagt man, da seht ihr es: Das ist einmal in der Welt geschehen! Da war in der Welt ein riesiger Gasball, bloß Gas; aber gedreht hat sich die Geschichte, und beweglich war es. Und dann sind halt die äußeren Dinge geradeso abgespalten worden, unsere Erde von der Sonne, wie da diese Oltröpfchen abgespalten wurden. - Das können sie schon in der Schule beweisen. Und die Kinder, die ja an die Autorität glauben, die sagen: Das ist ganz natürlich zugegangen; da war einmal ein riesiger Gasball, der hat sich gedreht, und da sind die Planeten abgespalten worden. Wir haben es selber gesehen, wie die Oltröpfelchen abgespalten worden sind.

Nun müssen Sie aber auch die Kinder fragen: Habt ihr denn auch gesehen, wie da oben der Schulmeister an dem Stecknadelkopf gedreht hat? Also müßt ihr euch einen riesigen Schulmeister dazu denken, der dazumal den Gasball gedreht hat, sonst hätten sich ja die Planeten nicht abspalten können! — Der Riesenschulmeister - im Mittelalter hat man ihn gezeichnet: das war der Herrgott mit dem langen Bart. Das war der Riesenschulmeister, und den vergessen diese Leute.

Aber es ist keine Erklärung, wenn man da einen Riesengasball annimmt, der sich dreht, und der sich erst drehen könnte, wenn einmal ein riesiger Weltenschulmeister dagewesen wäre. Das ist keine Erklärung. Aber, meine Herren, das ist eine Erklärung, wenn man darauf kommt, daß Sonne und Mond mit der Erde verbunden waren, und das sich selber bewegt hat. Das konnte sich bewegen. Ein Gasball, der kann sich nicht allein bewegen. Aber das, was ich Ihnen hier erklärt habe, das konnte sich bewegen. Dazumal brauchte es nicht einen Weltenschulmeister, sondern das war in sich selbst lebendig. Die Erde war eben einmal ein lebendiges Wesen, und zwar ein solches, wie heute ein Samenkorn es ist, und hat Sonne und Mond in sich gehabt. Sonne und Mond sind herausgegangen aus der Erde und haben ihre Erbschaft zurückgelassen, so daß heute die Keimkraft, die geschützt ist im mütterlichen und väterlichen Leibe des Menschen, diese Kräfte, die einstmals direkt von der Sonne kommen konnten, sich noch fortpflanzen und heute die Tiere, die Samen und Eier in sich entwickeln, die uralte Sonnenkraft in ihrer Eier- und Samenflüssigkeit in sich tragen, aus uralten Zeiten als Erbschaft in sich tragen von den Zeiten, wo die Erde selber noch Sonne und Mond in sich gehabt hat.

Sehen Sie, das ist eine wirkliche Erklärung, und nur wenn man es so versteht, kommt man zu einem wirklichen Verständnis. Dann begreift man, daß es einmal eine Zeit gegeben hat, wo der Mond herausgeflogen ist, und die Erde mit dem Mond aus der Sonne herausgeflogen ist. Wir werden uns über diese Sache noch weiter verständigen zunächst am Samstag um neun Uhr. Es wird noch etwas schwer sein, trotzdem aber glaube ich, daß die Geschichte so ausschaut, daß man es begreifen kann.