The Building Concept of the Goetheanum

GA 289

25 August 1921, Dornach

Automated Translation

6. Guided tour of the Goetheanum

I would like to say a few words about the building concept, with the direct support of the building. From the outset, the view could arise that if one has to talk about such a building, it indicates that it does not make the necessary impression as an artistic work; and in many cases, what is thought about the building of Dornach, about the Goetheanum in the world, is thought from a false point of view influenced by a [one-sided] view. For example, the opinion has been spread that the building in Dornach wants to symbolize all kinds of things, that it is a symbolizing building. In reality, you will not find a single symbol in it when you look at it, as they are popular in mystical and theosophical societies. The building should be able to be experienced entirely from the ki-based feeling and has also been created from these artistic feelings in its forms, in all its details. Therefore, it must only work through what it is itself.

Explaining has become popular, and one then complies with such requests for explanations; but in mentioning this here before you, I also say that such an explanation of an artistic work always seems to me to be not only half, but almost completely unartistic, and that I will now give you a kind of lecture in front of the building, a lecture that I fundamentally dislike, if only because I have to speak to you in abstract terms about what emerged in my mind as details when designing the building, the models and so on, and what was created from life. I would rather speak to you about the building as little as possible.

It is already the case that a new style, a new artistic form of expression, is viewed with a certain mistrust in the present day. I can still hear a word that I heard many decades ago when I was studying at the Technical University [in Vienna], where Ferstel gave his lectures. In one of them, he says: “Architectural styles are not invented, an architectural style grows out of the character of a nation.” Therefore, Ferstel is also opposed to any invention of a desired new architectural style, a new type of construction. What is true about this idea is that the style, which is supposed to stylize the characteristics of a people, must emerge not from an abstraction, but from a living world view, which is at the same time a world experience and, from this point of view, comprehensively encompasses the chaotic spiritual life of contemporary humanity. On the basis of this thoroughly correct idea, it becomes necessary to transform what was characteristic of previous architectural styles into organic building forms by incorporating the symmetrical, the geometric-static, and so on.

I am well aware of what can be said – and, from a certain point of view, justifiably said – by those who have become psychologically attuned to previous architectural styles against what has been attempted here in Dornach as an architectural style: the transference of geometrical-symmetrical-static forms into organic forms. But it has been attempted. And so you can see in these forms of building that this building here is an as yet inadequate first attempt to express the transition from these geometric forms of building to the organic. It is certain, of course, that the development of humanity is moving towards these forms of building, and when we again have the impulses of clairvoyant experience, I believe that these forms of building will play the first, leading role.

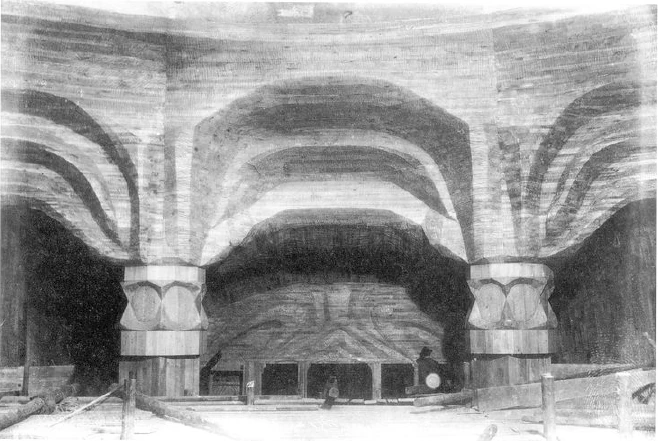

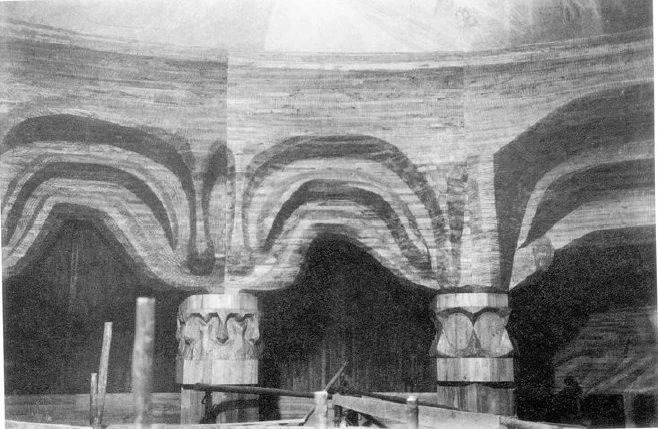

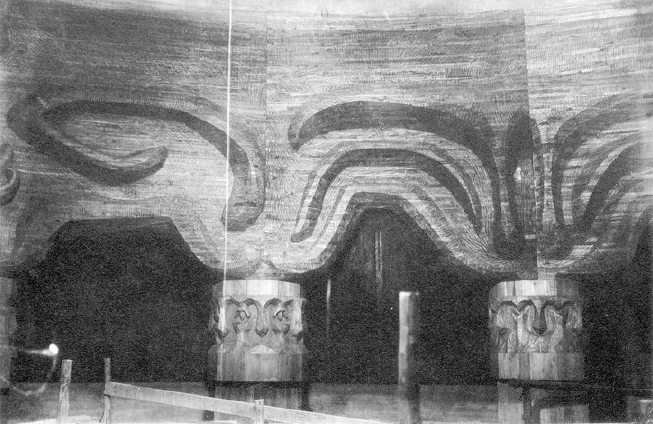

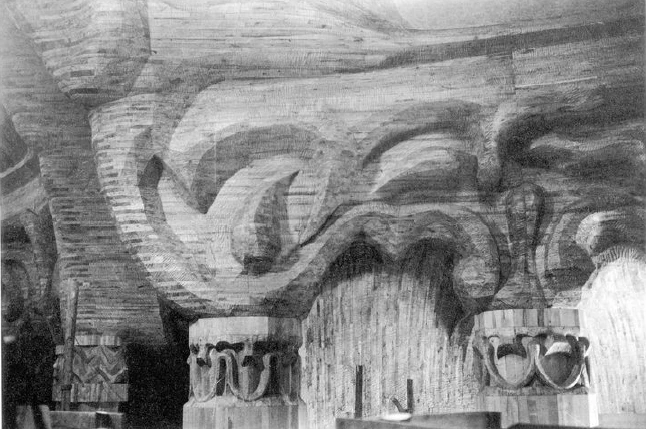

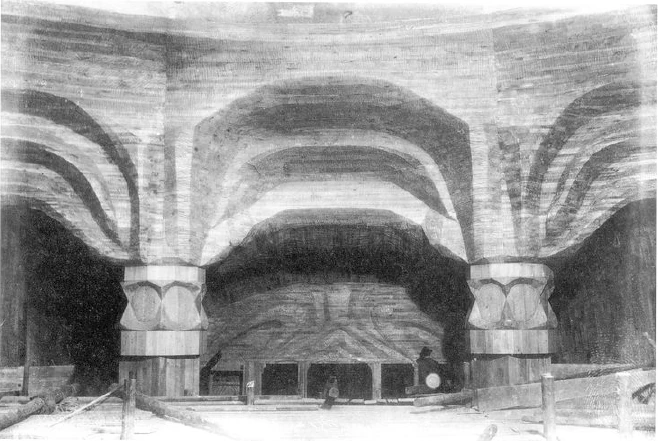

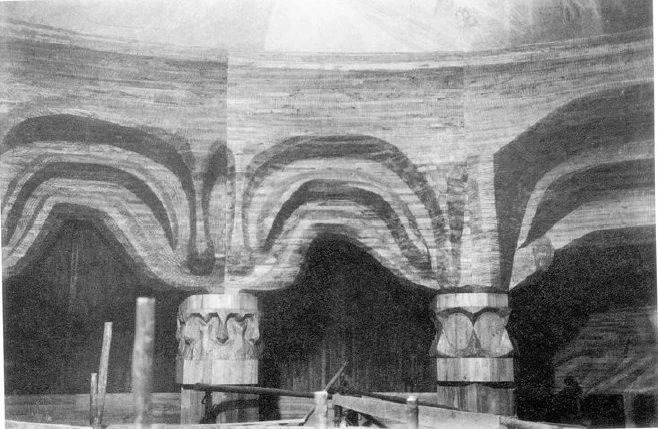

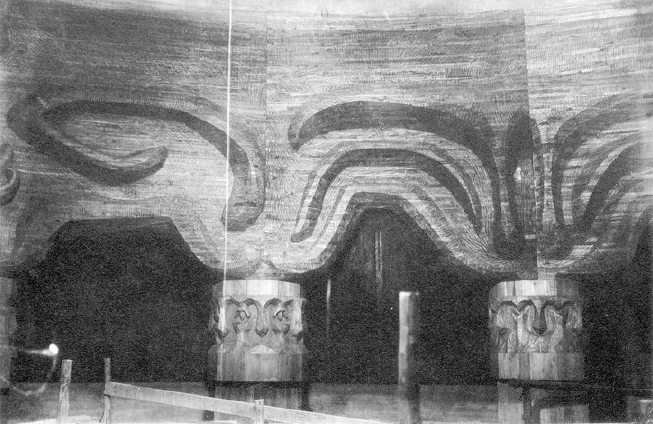

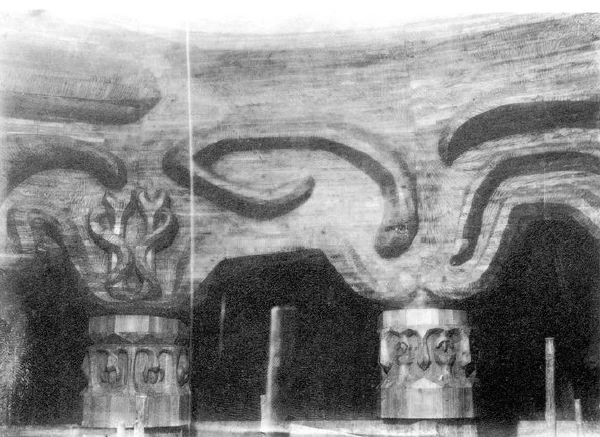

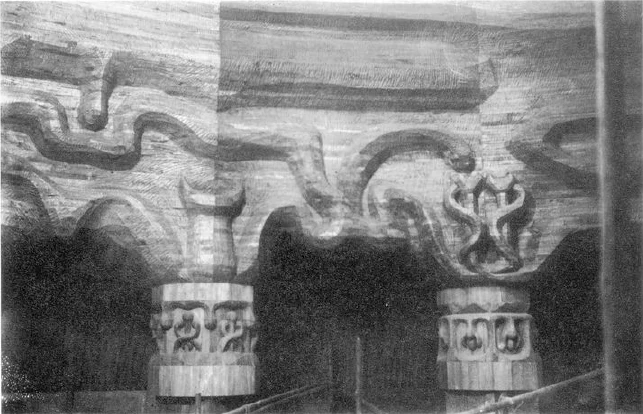

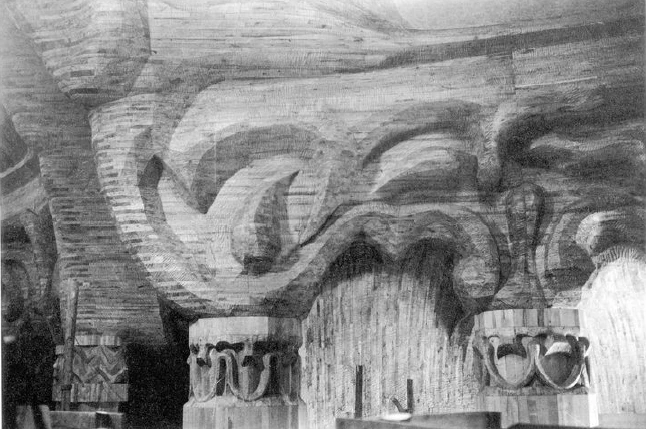

This building should be understood in the same way through its relationship with the organizing forces of nature as the previous buildings are understood through their relationship with the geometric-static-symmetrizing forces of nature. This building is to be viewed from this point of view, and from this point of view you will understand how every detail within the building idea for Dornach must be completely individualized here. Just think of your earlobe: it is a very small part of the human organism, but you cannot imagine that an organic form like the earlobe is suitable for growing on the big toe. This organ is bound to its place within the organism. Just as you find that within the whole organism a supporting organ is always shaped in such a way that it can have a static-dynamic effect within the organism, so too the individual forms in our building in Dornach had to be such that they could serve the static-dynamic forces. Every single form had to be organized in such a way that it could and had to be in its place what it now appears to be. Look at each arch from this point of view, how it is formed, how it flattens out towards the exit, for example, how it curves inwards towards the building itself, where it not only has to support but also to express support in an organic way, thereby helping to develop what only appears to be unnecessary in organic formation. Ordinary architecture leaves out what the organism develops, that which goes beyond the static. But one senses that the idea of building has been transferred to the organic design of the forms, and that this is also necessary.

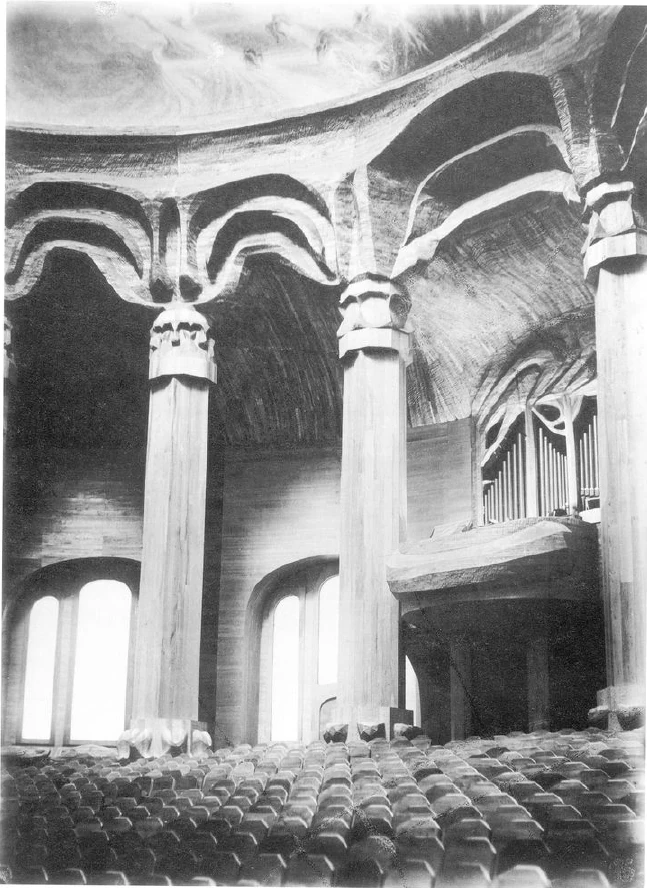

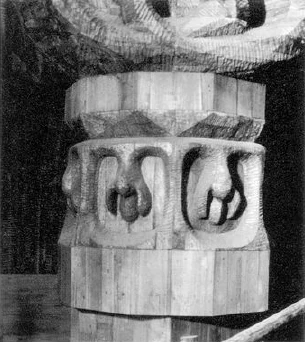

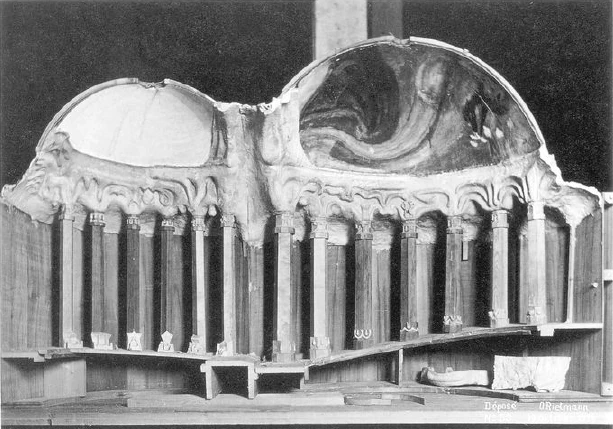

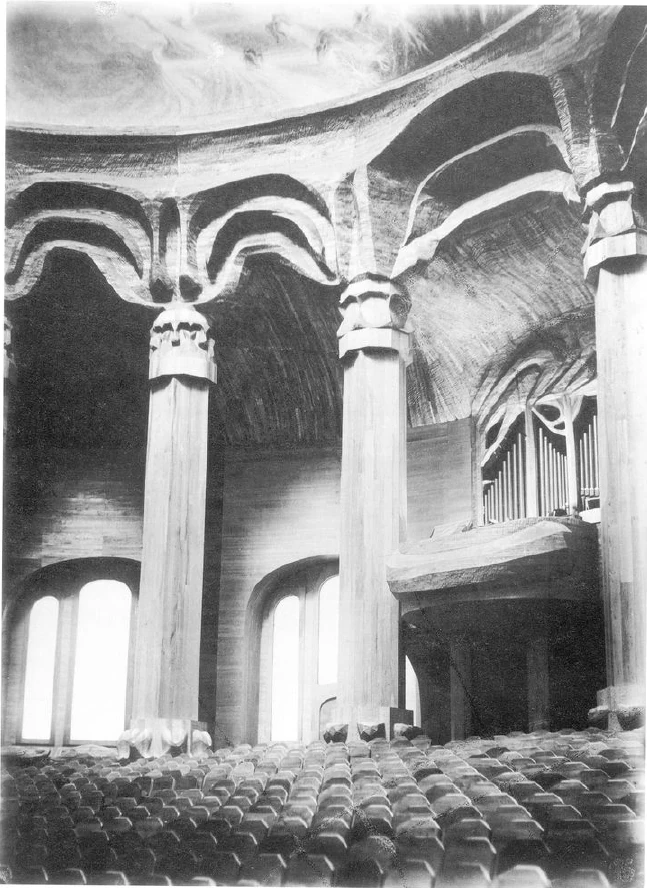

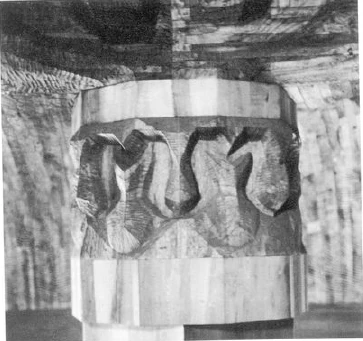

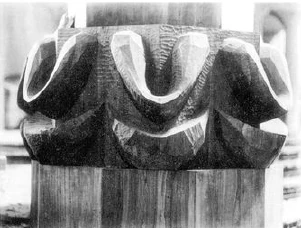

You will have to consider every column from this point of view; then you will also understand that the ordinary column, which is taken out of the geometric-static, has been replaced by one that does not imitate the organic - everything is so that it is not imitated naturalistically - but transferred into organically made structures. It is not imitating an organic structure. You will not find it if you look for a model in nature. But you will find it if you understand how human beings can live together with the forces that have an organizing effect in nature, and how, apart from what nature itself creates, such organizing forms can arise. So you will see in these column supports how the expansion of the structure, the support, the inward pointing, and, in the same way as, say, in the upper end of the human thigh, the support, the walking, the walking and so on, is embodied statically, but organically and statically.

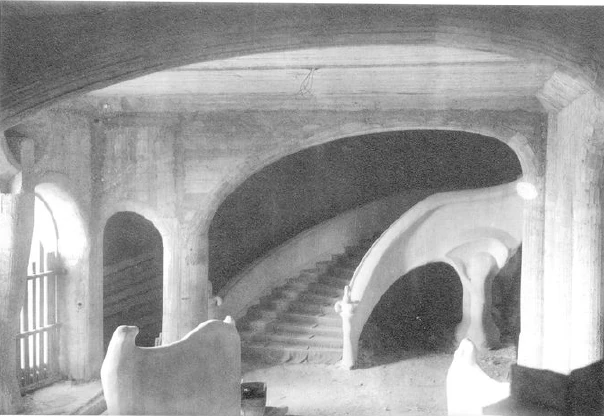

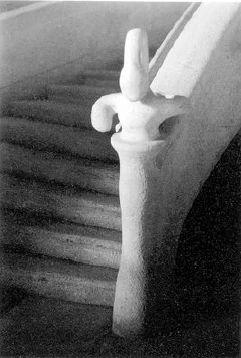

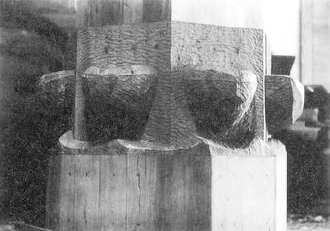

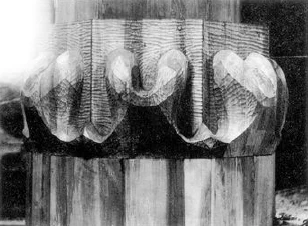

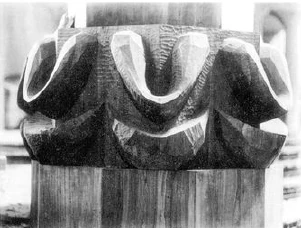

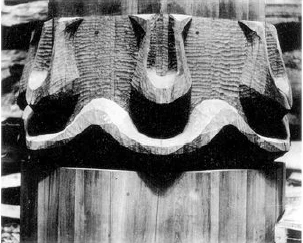

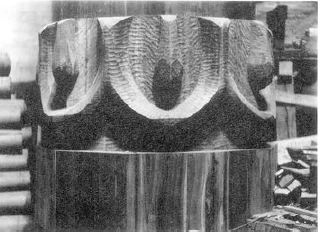

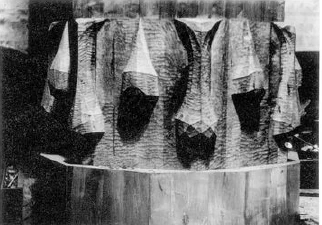

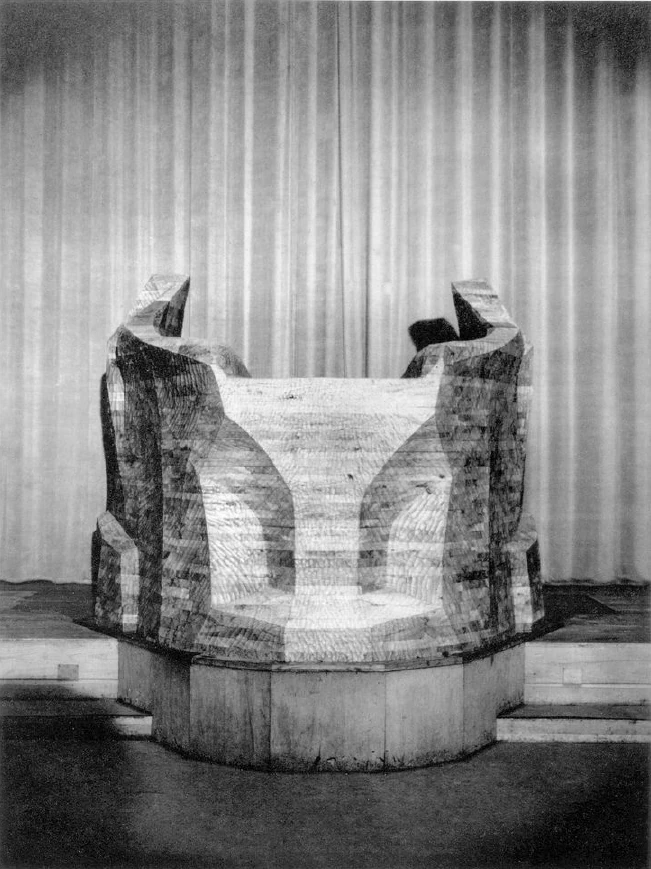

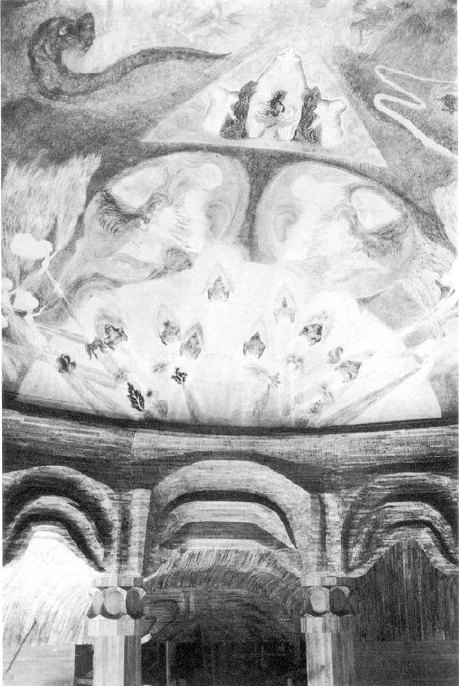

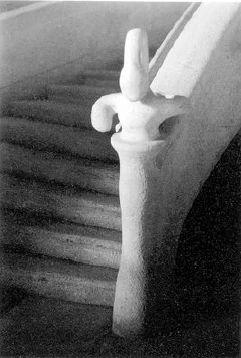

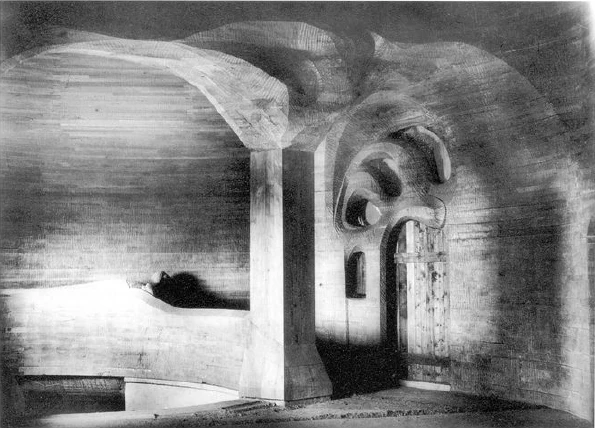

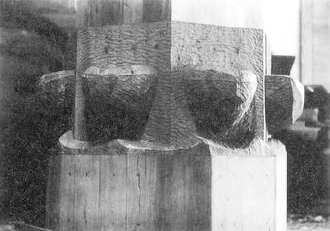

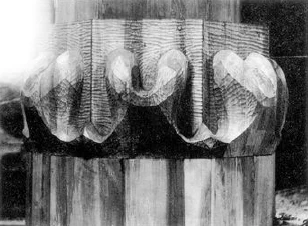

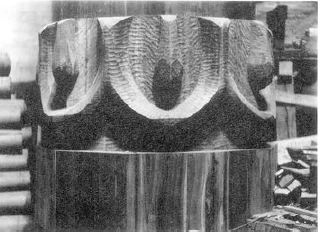

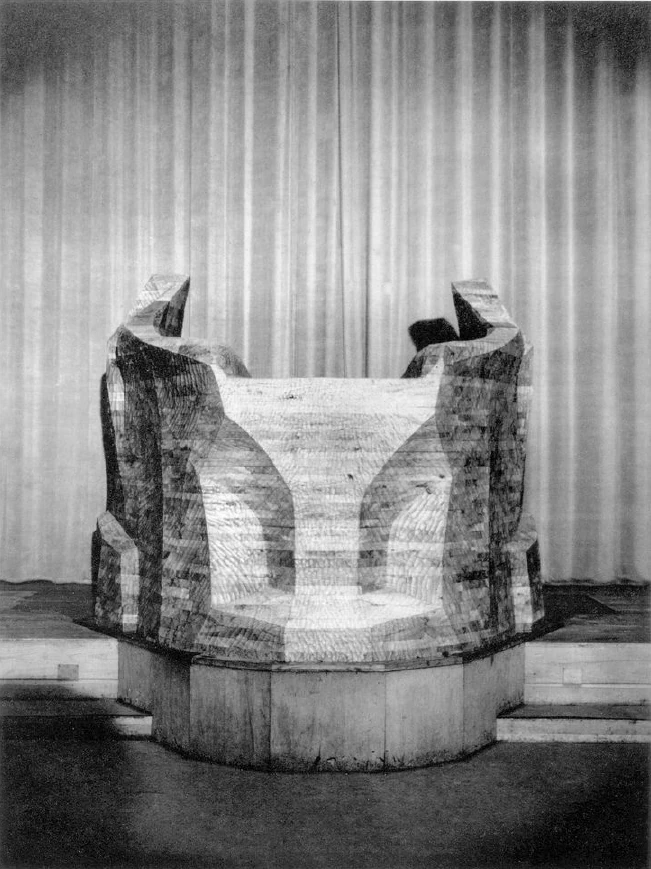

From this point of view, I would also ask you to consider something like the structure with the three perpendicular formations at the top of the stairs here below (Figs. 23, 24). The feeling arises here of how a person feels when he is striving to ascend the stairs. He must have a feeling of security, of spiritual unity in all that goes on in this building, indeed in all that he sees in this building. Everything came to me entirely from my feelings. Believe it or not, this form came to me entirely from my artistic feelings. As I said, you may believe it or not, it was only afterwards that it occurred to me that this form is somewhat reminiscent of the form of the three semicircular circles in the human ear, which, when injured, cause fainting, so that they immediately express what gives a person stability. This expression, that a person should be given stability in this building, comes about in the experience of the three perpendicular directions. This can be experienced in this structure without having to engage in abstract thought. One can remain entirely in the artistic realm.

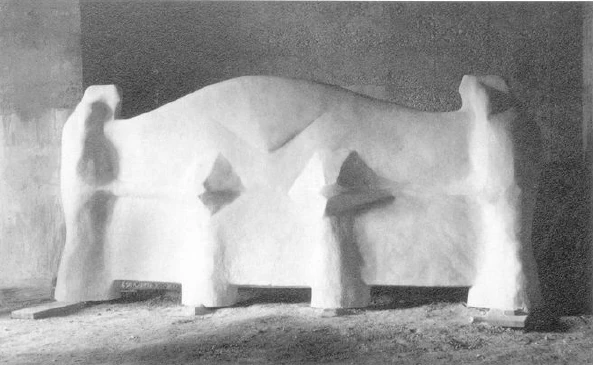

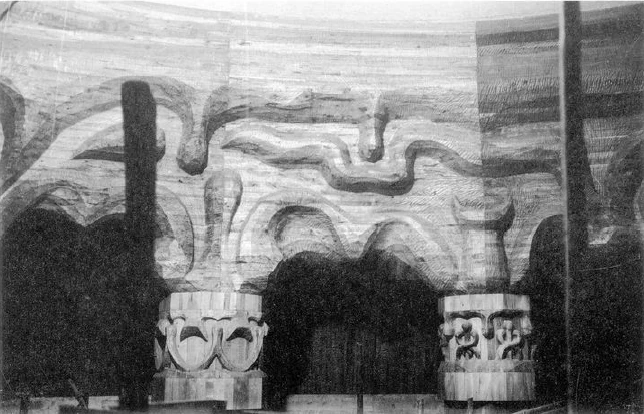

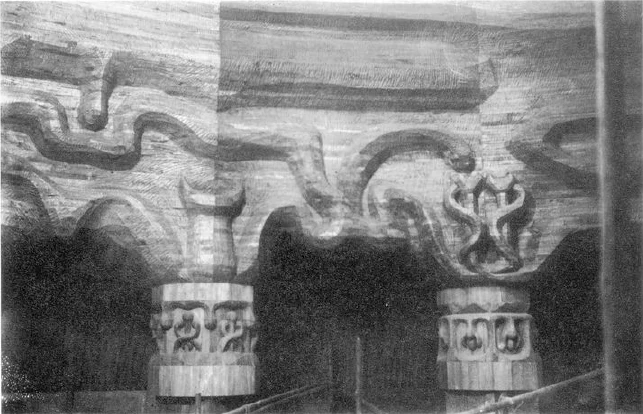

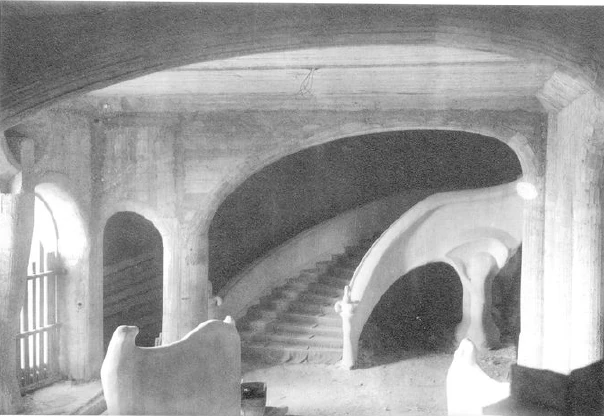

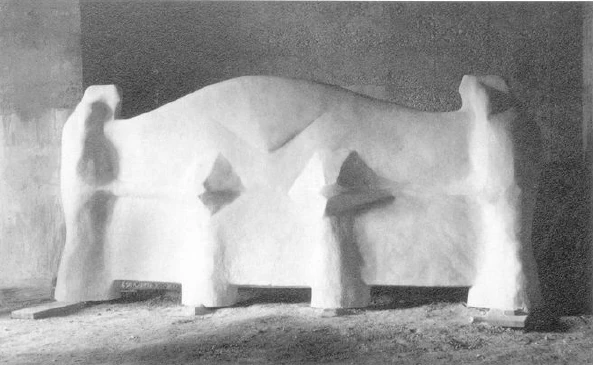

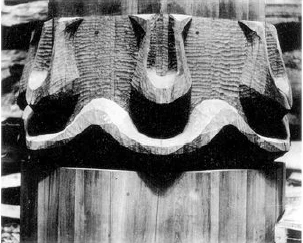

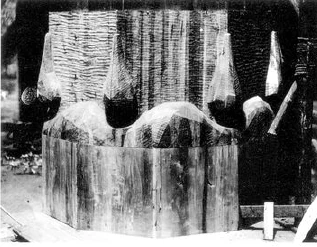

If you look at the wall-like structures, you will find that natural-looking forces have been poured into the forms, but in such a way that in these forms, which are radiator covers (Fig. 26), the concrete material of the structure is worked out first, and then, further up, the material of the wood, so that they are metamorphosed. You will find that in these structures, the process of metamorphosis is elevated to the artistic. It is the idea of the building that should have a definite effect on such radiator covers, which are designed in such a way that you immediately feel the purpose and do not need to explore it intellectually first. This is how these elementary forms, half plant-like, half animal-like, came to be felt. One only realizes that they must be so when one has shaped them out of the material. And it also follows that it is necessary to metamorphose them depending on whether they are in one place or another, depending on whether they are long and low or narrower and higher. All this is not the result of calculating the form, but the forms shape themselves out of the feeling in their metamorphosis, as for example here, where we have come so far, where the building is a concrete structure in its basement and where one has to empathize with the design of what the concrete is. You enter here at the west gate. Here is the room for checking in your coat. The staircase, which leads up on the left and right, takes you up to the wooden structure containing the auditorium, the stage and adjoining rooms. Please follow me up the stairs to the auditorium.

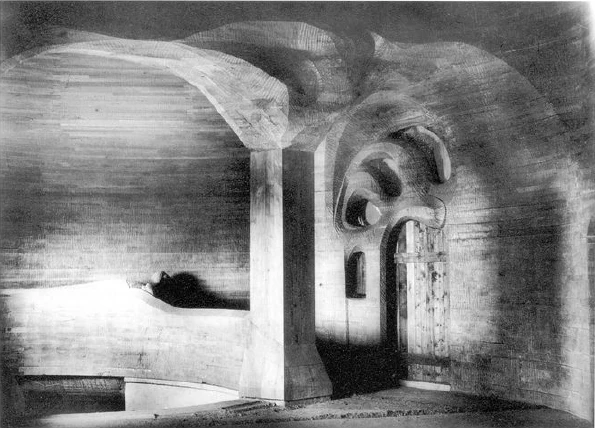

We first enter a kind of vestibule (Fig. 27). You will feel the very different impression that the wooden paneling creates compared to the concrete paneling on the lower floor. I would like to note here: When one has to work with stone, concrete or other hard materials, one has to approach it differently than when one has to work with a soft material, for example, wood. The material of wood makes it necessary to focus one's entire perception on the fact that one has to scrape corners, concaves, and hollows out of the soft material, if I may use the expression. It is scraping, scraping out. You deepen the material, and only by doing so can you enter into this relationship with the material, which is a truly artistic relationship. While when working with wood you can only coax out of the material what gives the forms if you focus your attention on deepening, when working with hard material you do not have to do with the recesses. You can only develop a relationship with the hard material by applying it, by working convexly, by applying raised areas to the base surfaces, for example when working with stone. Grasping this is an essential part of artistic creation, and it has been partially lost in more recent times.

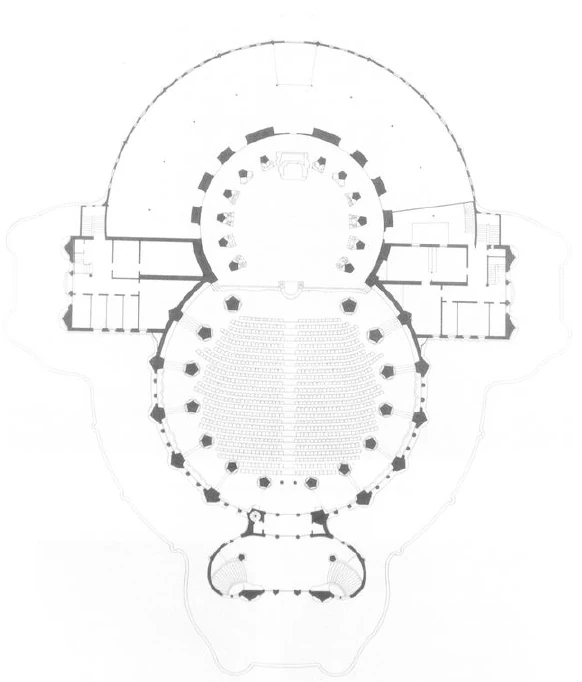

You will see when we enter the auditorium how each individual surface, each chapter, is treated individually. In this organic structure, a chapter can only be such that one feels: In what follows each other, no kind of repetition can be created, as is otherwise the case with symmetrical-geometric-static architectural styles. In this building, based on organic ideas, you have only a single axis of symmetry, which goes from west to east. You will only find a symmetrical arrangement in relation to this, just as you can only find a single axis of symmetry for a higher organism, not out of arbitrariness, but out of the inner organization of forces of the being in question.

At this point, I would also like to mention that the treatment of the walls also had to be completely different under the influence of the organic building idea than it was before. A wall was for earlier architects what demarcates a space. It had the effect of being inside the room. This feeling had to be abandoned in this building. The walls had to be designed in such a way that they were not felt as a boundary, but as something that carries you out into the vastness of the macrocosm; you have to feel as if you are absorbed, as if you are standing inside the vastness of the cosmos. Walls had to be made transparent, so to speak, whereas in the past every effort was made to give the wall such artificial forms that it was closed, opaque. You will see that the transparent is used artistically at all, and that was driven out of elementary backgrounds into the physical in these windows that you see here and that you will see in the building.

If you see windows in the sense of the earlier architectural style, you will actually have to have the healthy sense: they break through the walls, they do not fit into the architectural forms, but they only fit in through the principle of utility. Here, artistic feeling will be needed down to the last detail. It was necessary to present the wall in such a way that it is not something closed, but something that expands outwards, towards infinity. I could only achieve this by remembering that you can scratch out designs from single-colored window panes, as if using an erasing method, a glass etching method. And so, monochromatic window panes were purchased, which were then processed in such a way that the motifs one wanted to have were scratched out with the diamond stylus. So for this purpose, an actual glass etching technique was conceived, and from this the windows emerged.

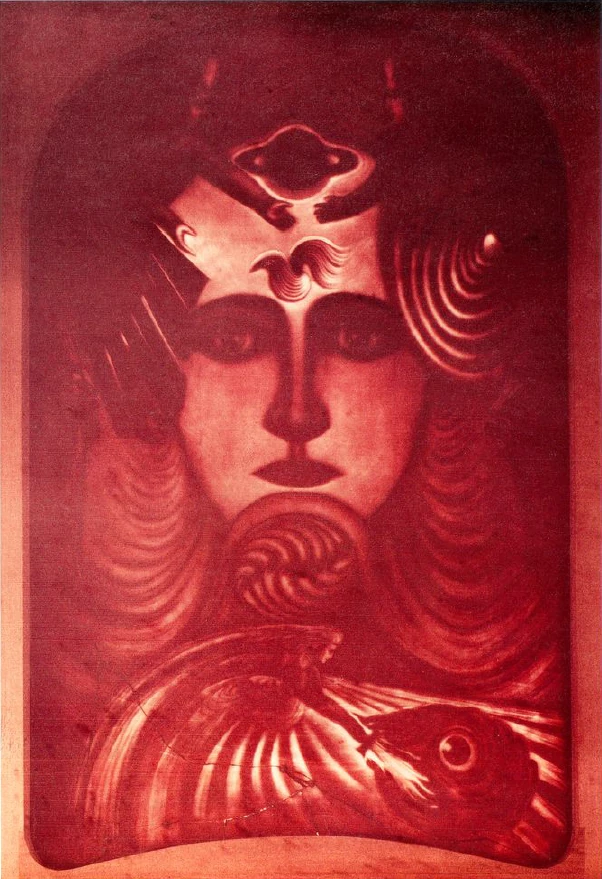

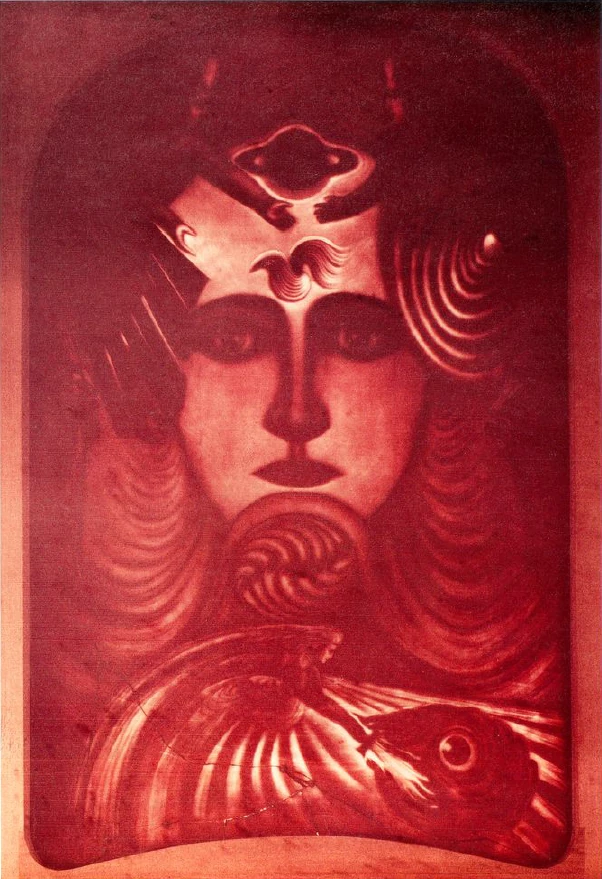

When you consider the motifs of the windows, you must not think that you are dealing with purely symbolic designs. You can see it already on this larger windowpane (Fig. 109): nothing is designed on these window panes other than what the imagination produces. There are mystics who develop a mysticism with superficial sentences and strange ideas and constantly explain that the physical-sensual outer world is a kind of maja, an illusion. Often people approach you and say that so-and-so is a great mystic because he always declaims that the outer world is a maja. The human physical countenance has something that is maya, that is absolutely false, that is something quite different in truth. What appears on this windowpane is not something that symbolizes; it is an essence that is envisaged, which only does not look to the spiritual observer as it appears to the senses. The larynx is the organ of vision for the etheric; the larynx is already Maja as a physical larynx, and that which is a merely physical-sensual vision is not reality.

What is the spiritual meaning behind this? The spiritual fact is that the human being is truly being whispered in the ear, left and right, what the secrets of the world are. So that one can say: the bull speaks in the left ear, the lion in the right ear. If one wants to depict something like this as a motif in a picture or in words, one can only put into the word what is already in the picture itself. It must be clearly understood, however, that such a picture can only be understood by someone who lives in the world view from which it originated. A person who does not have a living Christian feeling will not be able to relate to the pictorial representations that Christian art has produced.

The artist experiences a great deal when he immerses himself in a vision; but such an experience must not be translated into abstract thoughts, otherwise it will immediately begin to fade. One example of the artist's experience is this: when Leonardo da Vinci painted his Last Supper, which has now fallen into such disrepair that it can no longer be appreciated artistically, people thought it took too long. He couldn't finish the Judas because this Judas was supposed to emerge from the darkness. Leonardo worked on this painting for almost twenty years and still hadn't finished it. Then a new prior came to Milan and looked at the work. He wasn't an artist; he said that Leonardo, this servant of the church, had to finally finish his work. Leonardo replied that he could do it now; he had always only sketched the figure of Judas because he had not found the model for it; now that the prior was there, he had found the model for Judas in him, and the picture would now be quickly finished. — There you have such an external, concrete experience. Such external, concrete experiences play a much greater role in all the artist's work than can be expressed in such brief descriptions.

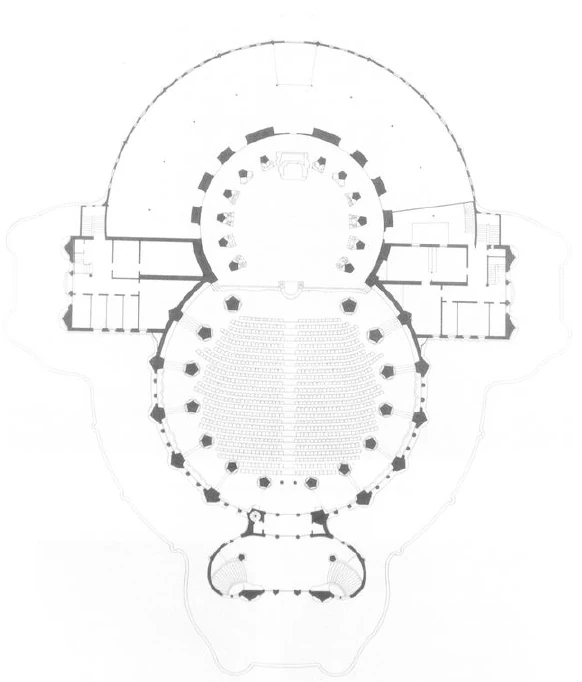

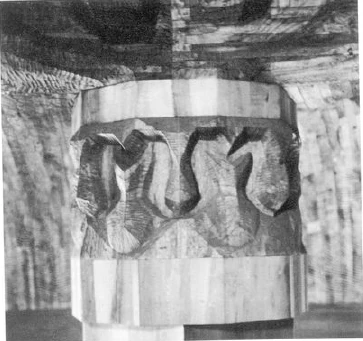

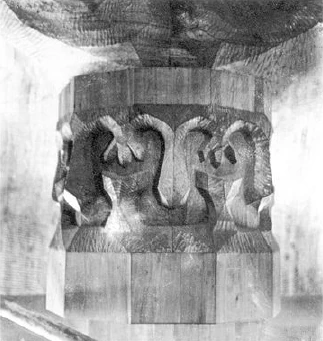

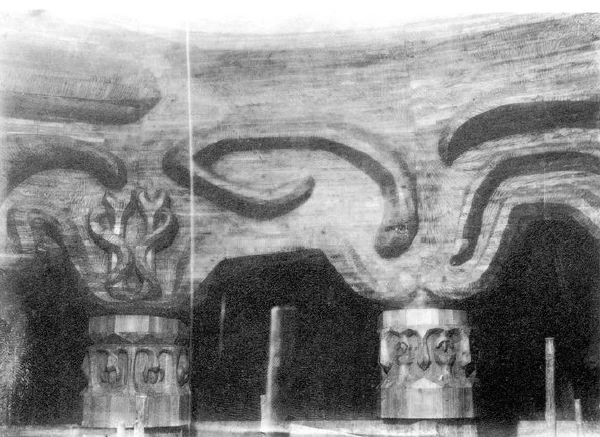

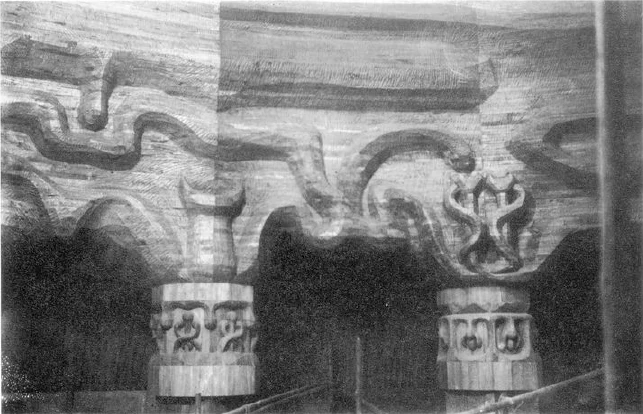

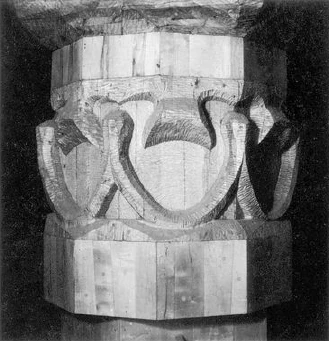

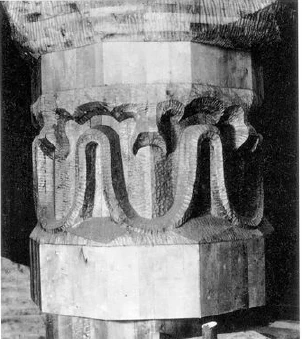

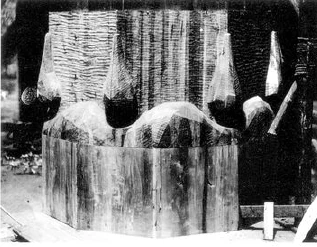

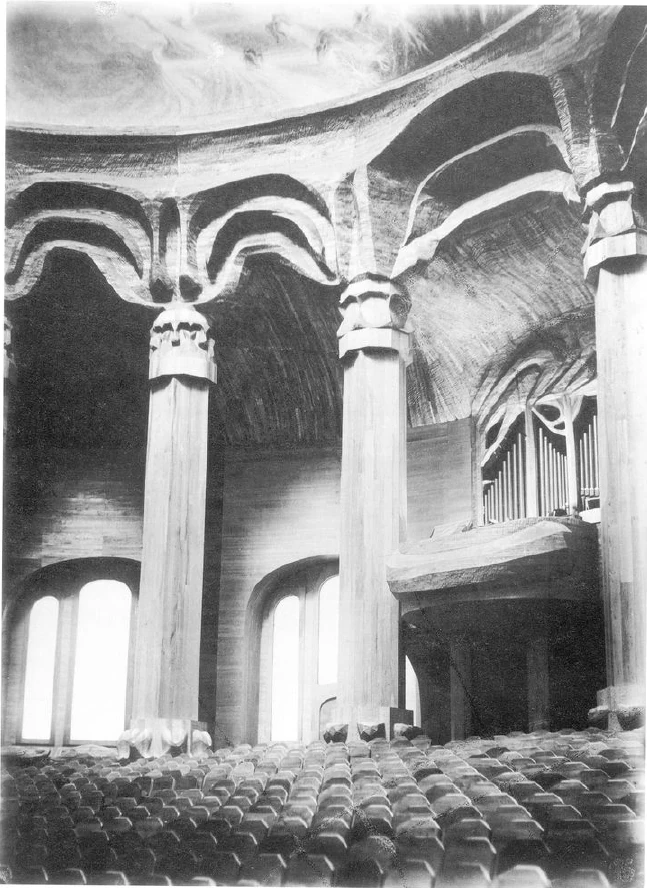

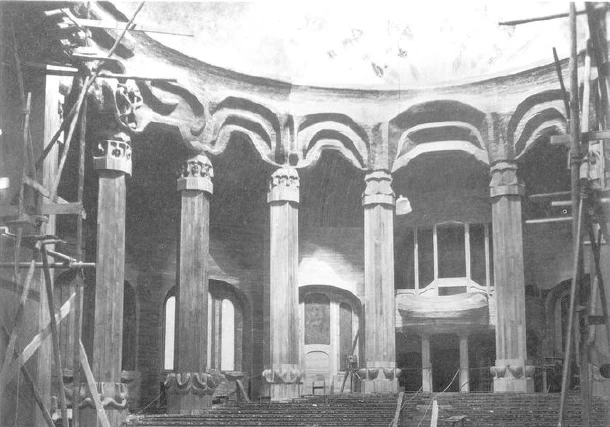

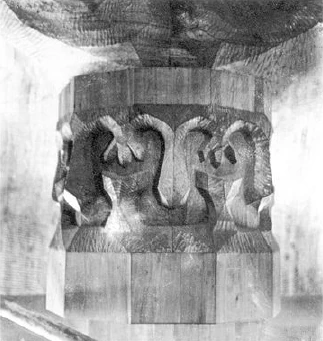

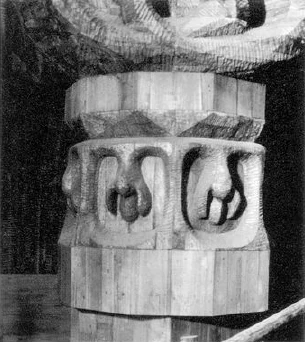

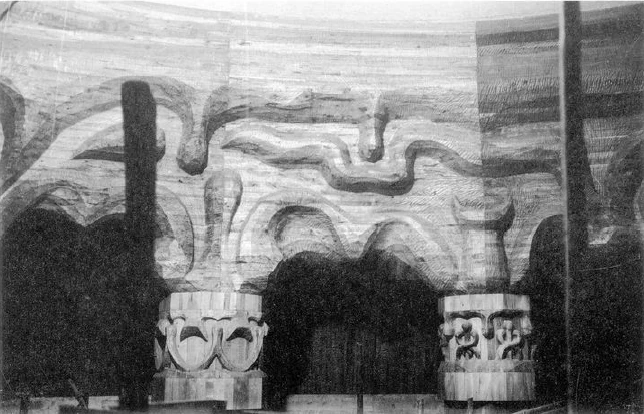

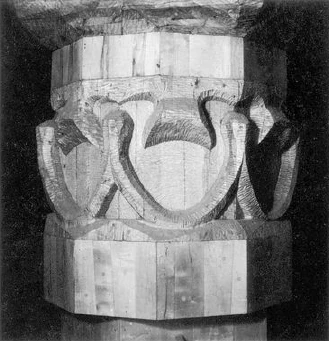

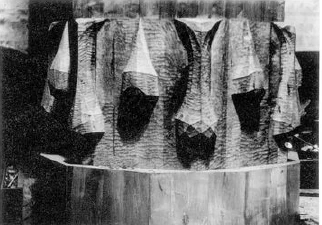

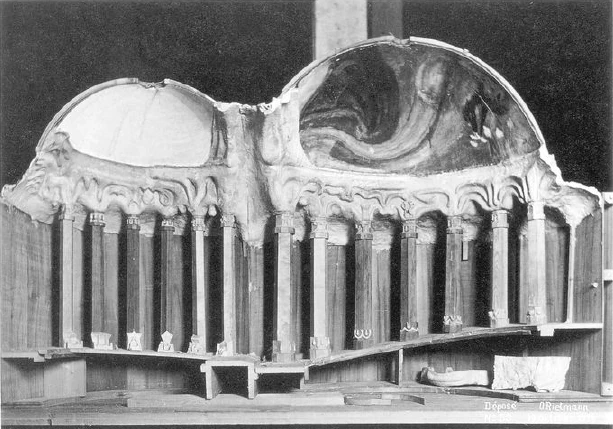

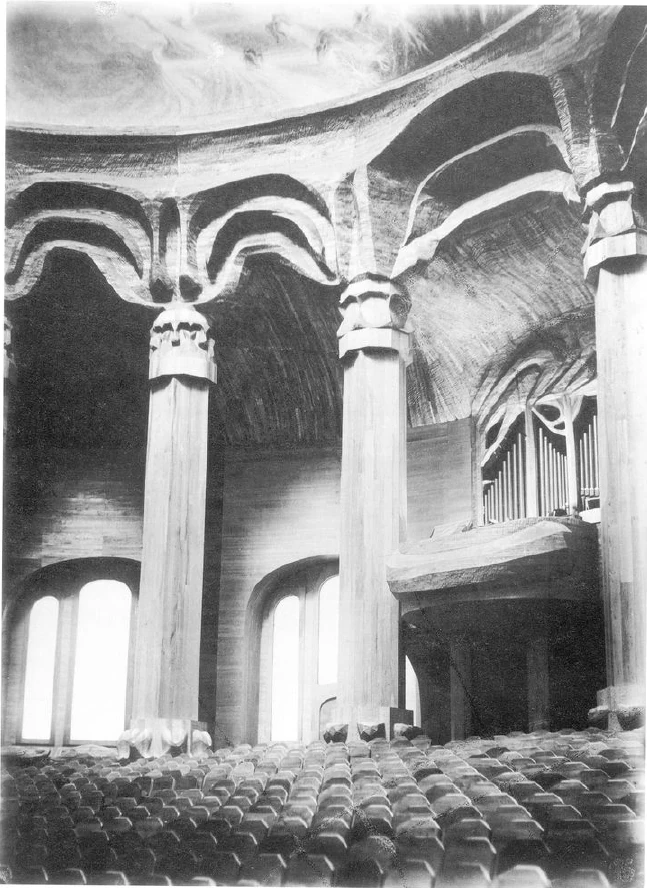

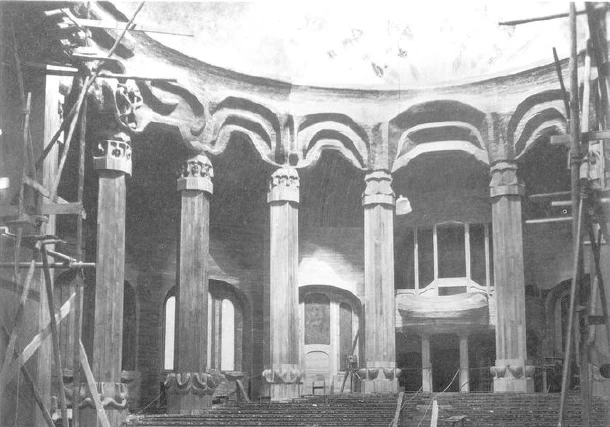

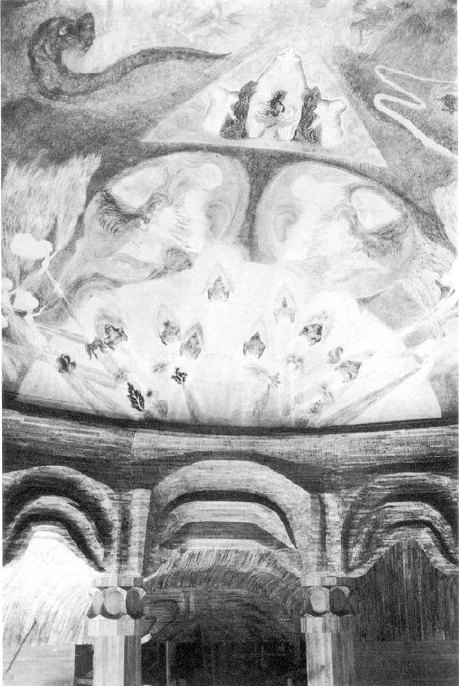

You have [now] entered the building through the room below the organ and the room for musical instruments, dear attendees. If you look around after entering, you will find the building idea initially characterized by the fact that the floor plan (Fig. 20) represents two not quite completed circles that interlock in their segments. It seems to me that the necessity for shaping the building in this way can already be seen when approaching the building from a certain distance and if one has an idea of what is actually supposed to take place in the building. I will now explain further what is connected with the building idea. First of all, I would like to point out that you can see seven columns arranged in symmetry solely against the west-east axis, closing the auditorium on the left and right as you move forward. These seven columns are not formed in such a way that a capital shape, a pedestal shape or an architrave shape above it is repeated, but the capital, pedestal and architrave shapes are in a continuous development. The two columns at the back of the organ room have the simplest capital and pedestal motifs (Figs. 28, 33): forms that, as it were, strive from top to bottom, with others striving towards them from bottom to top. This most primitive form of interaction between above and below is then metamorphosed in the following architrave, capital and pedestal forms (Figs. 35-54).

This progressive metamorphosis came about through the fact that, when I was forming the model (Fig. 22), I tried to recreate what occurs in nature by force. What happens in nature, where an unnotched leaf with primitive forms is first formed at the bottom of the plant, and then this primitive form metamorphoses the higher you go, into the indented, more intricately designed leaf, even transformed into a petal, stamen and pistil, which must be imitated - although not in a naturalistic way - one must place oneself inwardly and vitally into it and then create from within, as nature creates and transforms, as it produces and metamorphoses. Then, without reflection, but from much deeper soul forces than from reflection, one gets such transformations of the second from the first, the third from the second, and so on.

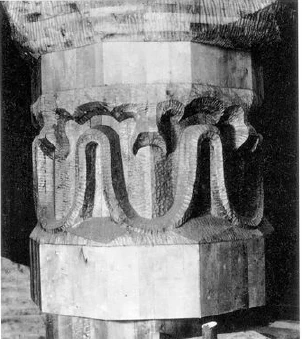

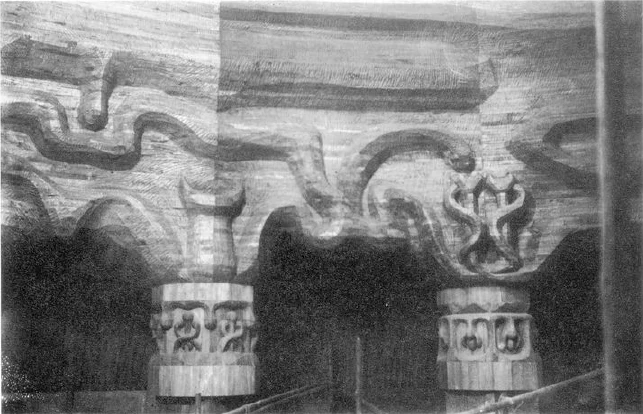

It is possible to misunderstand that, for example, in the fifth column and in the architrave motifs above the fourth column, something like a caduceus appears (Figs. 41, 42). One could now believe that the caduceus was stuck in these two places by the intellect. I believe that someone who had worked from the intellect would probably have placed the caduceus in the architrave motif and, because the intellect has a symmetrical effect, the column motif with the caduceus below it. Someone who works as we have here finds something different. Here, with the motif that you see as the fourth capital motif, this Mercury staff emerged just as a petal emerges from the sepal, only through sensing the metamorphosing transformation, without me even remotely thinking of forming a Mercury staff. I did not think of a past style, but of the transformation of the fourth capital motif from the third. One can see how the forms that have gradually emerged in the development of humanity have developed quite naturally.

Then we come to the epoch when the human being intervenes in his or her psychological development. If we work this into the column in an individualizing way, what is worked on earlier on the surface of the architrave comes later. That is why you see the caduceus on the capital later than on the architrave. A plant that is thin and delicate develops different leaf shapes than a sturdy one. Compare just a shepherd's purse with a cactus, and you will see how the filling and shaping of space is expressed in the figurative design.

At the same time, a cosmic secret arises in this way of feeling evolution through. There has been much talk of evolution in recent times, but little feeling about it. One only thinks it through with the mind. One speaks of the evolution of the perfect from the imperfect. Herbert Spencer and others have done much harm to this, and the thought has arisen that is completely justified in front of the mind, but which does not do justice to the observation of nature: In intellectual thinking, one assumes that in evolution, the simpler forms are at the beginning and that these then become more and more differentiated and differentiated. Spencer, in particular, worked with such evolutionary ideas. But evolution does not show it that way. There is, however, a differentiation, a complication of the forms; but then one comes to a center, and then the forms simplify again. What follows is not more complicated, but what follows is simpler again. You can see this in nature itself. The human eye, which is the most perfect, has, so to speak, achieved greater simplicity than the eye forms of certain animals, which, for example, have the xiphoid process, the fan, which has disappeared again as the eye in evolution moved further up to become human.

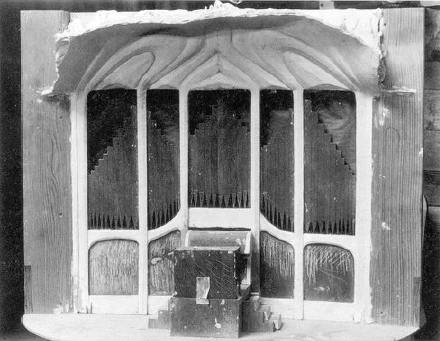

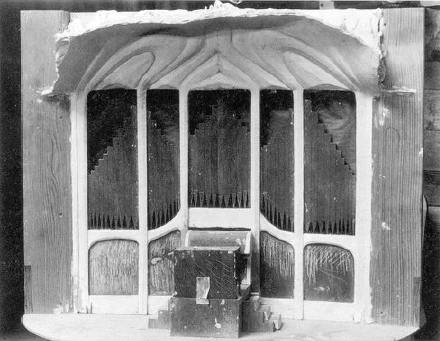

It is therefore necessary for man to connect with the power of nature, to feel the power of nature, to make the power of nature his own power and to create from this feeling. Thus, an attempt has been made to design this building in an entirely organic way, to design every detail in its place as it must be individualized from the whole. So you can see, for example, that the organ (Figs. 28-30) is surrounded by plastic motifs that make it appear as if the organ is not simply placed in the space, but that it works out of the whole remaining organic design, as if growing out of it. So everything in this building must be tried to be made in this way.

Here you see the lectern (Fig. 68) on which I am standing. Initially, the idea was to create something here that would, as it were, grow out of the other forms of construction, but in such a way that it would also express the fact that from here, through the word, one strives to express everything that is to be expressed in the building. At the moment when a person speaks here, the forms of what is spoken must continue in such a way that, just as the nose betrays in its form what the whole person is through his or her countenance, so too can the forms of what is spoken continue in such a way that the whole human being is revealed through the form of the nose. Anyone who has made artistically inspired nose studies can create the 'architectural style', the physiognomy of the whole human being, from a nose study. No one can ever have a different nose than they have, and there could never be a different lectern than the one that is here. However, if you claim this, it is meant according to your own view; you can only act according to your own view.

That an attempt has been made here to truly metamorphose the body can be seen from the fact that the motifs here in the glass windows are in part really such motifs that arise as images of the soul's life. For example, look at the pink window here (Fig. 113). You will see on the left wing something coming out like the west portal of the building; on the right wing you see a kind of head. There you see a person sitting on a slope, looking towards the building, and another person looking towards the head. This has nothing to do with speculative mysticism; it has to do with an immediate inner visual experience. This building could not have been created in any other way than by sensing the shape of the human head in a mysterious way, and the organic power on the one hand and the shape of the human head on the other hand result in the intuitive shape of the building. Therefore, the person sitting on the slope sees the metamorphosis of the building in his soul, sometimes as a human head, sometimes as the building revealing itself to the outside world. This provides a motif that leads, if I may say so, to an inner experience.

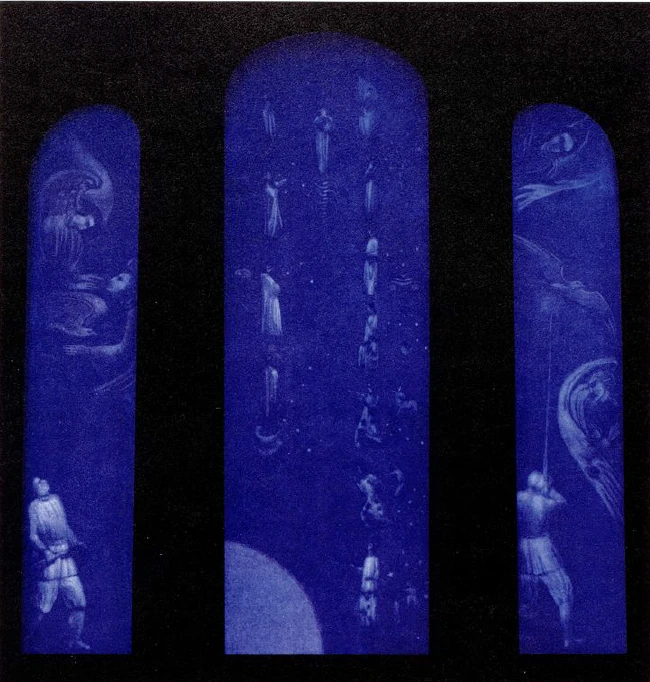

There you will find in the blue windowpane (Fig. 111) a person who is aiming to shoot a bird in flight. In the right-hand pane you will see that the person has fired. The bird in the left-hand field is in a sphere of light. Around the man you find all kinds of figures vividly alive in the astral body, one when he is about to shoot, the other when he has shot. This is reality, but it is from mundane life. I can imagine that those who always want to be dripping with inner elevation take offence when they experience such things as they are meant here, that a human shooting is simply depicted. Yes, I was pleased when an Italian friend once used a somewhat crude expression about theosophists, who are such mystics. The friend who had already died said it, and I may say it in the very esteemed company here, because the person concerned was a princess, and what a princess says can certainly be said. She glossed such people, who always want to live in a kind of inner elevation, by saying that they are people with a “face up to their stomachs”. I also do not repeat her not quite correct German.

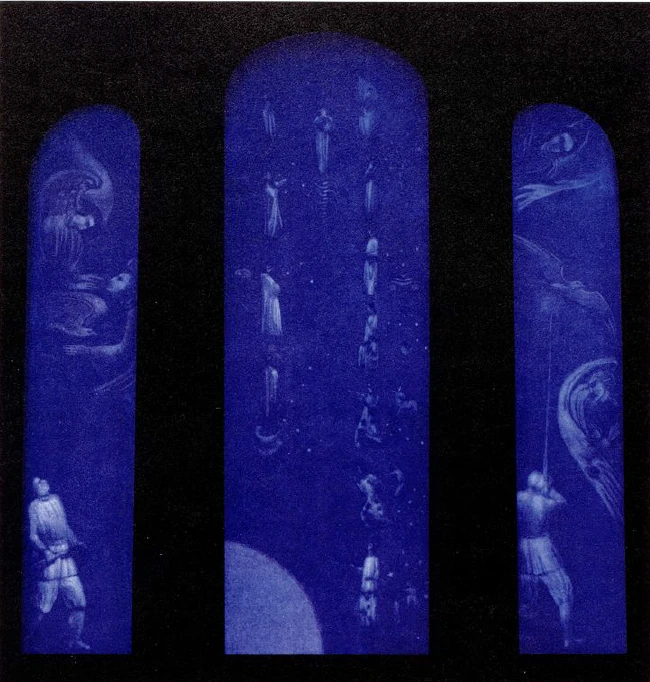

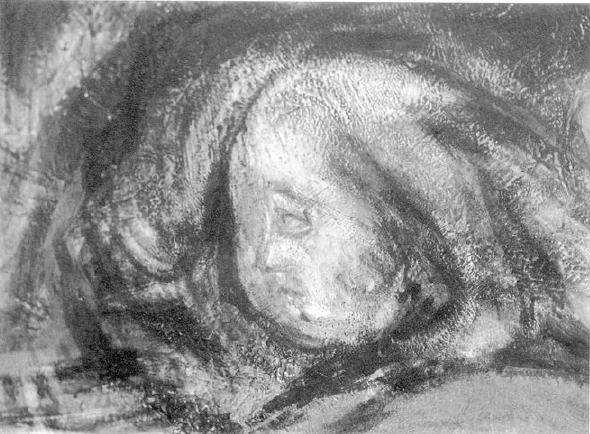

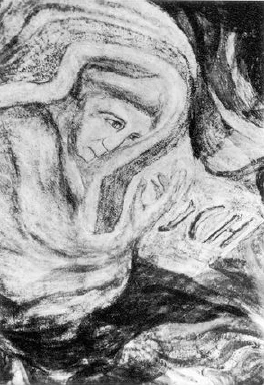

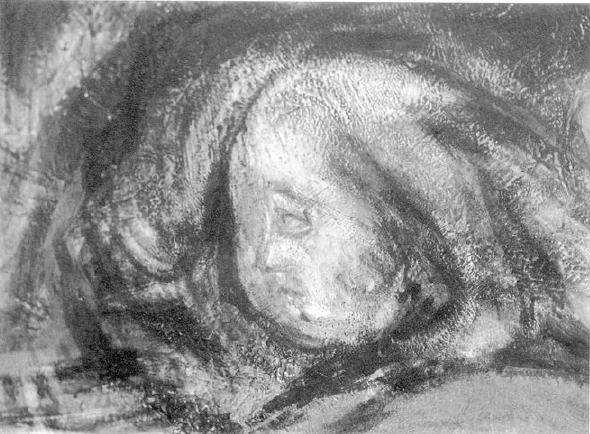

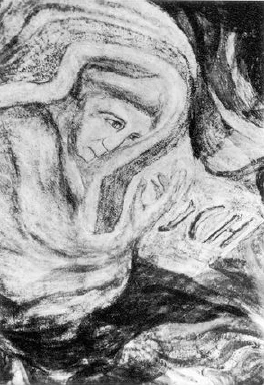

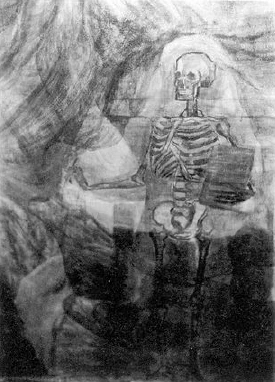

Now, dear attendees, the same idea was then also implemented in painting. I can only talk about the actual painting, about spiritual painting, by referring to the small dome. Only in the small dome was it possible for me to carry out what I have indicated as the challenge of a newer painting: that here, behind the emergence from the color experience, drawing disappears altogether. I had one of my characters in the first mystery drama express this as follows: that the forms appear to be the work of color. For when one feels with the feeling for painting, then one feels the drawing, which is carried into the pictorial, as a lie. When I draw a horizontal line, it is actually a reproduction of something that is not there at all. When I apply the blue sky as a surface and the green below, the form arises from the experience of the color itself. In this way, every pictorial element can be formed. Within the world of color itself lies a creative world, and the one who feels the colors paints what the colors say to each other in creation. He does not need to stick to a naturalistic model; he can create the figures from the colors themselves. It is the case that nature and also human life already have a certain right to shape the moral out of the colored with a necessity.

Yesterday, Mr. Uehli quite rightly pointed out how newer painters already have an intuitive sense of such effects created by light and dark, by the colors themselves, and how they come to paint a double bass next to a tin can. They are pursuing the right thing in and of itself, that it is more important to see how the light gradates in its becoming colored when it falls on a double bass and then continues to fall on a tin can. That is the right thing. But the wrong thing is that this is again based on naturalistic experience. If you really live in the colors, something other than a tin can and a bass violin arises from the colors. The colors are creative, and how they come together is a necessity arising from the mere colors, which you have to experience. Then you don't put a tin can next to a bass violin because that is outside the colors.

So here I have tried to paint entirely from the colors. If you see the reddish-orange spot and the black spot next to the blue spot, it is first of all a vivid impression from the colors. But then the colors come to life, then figures emerge from them, which can even be interpreted afterwards. But just as little as one can make plants here with the human mind, one can just as little paint something on them that one has thought up with the human mind. One must first think when the colors are there, just as the plant must first grow before one can see it.

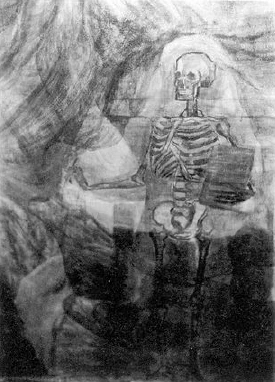

And so a Faust figure with Death and the Child came into being (Figs. 69-74). The whole head emerged out of the colors, with all the figures in it. Only in the realm of the human soul does something spiritually real take shape of its own accord. For example, you can see above the organ motif how something is painted (Fig. 31) that a person with a philistine attachment to the sensual world would naturally perceive as madness. But you will no longer perceive it as madness when I tell you the following: if you close your eyes, you will, as it were, feel something like two eyes looking at each other, inside the eye. What takes place inwardly can certainly be further developed in a certain way. Then what, when viewed in a primitive way, looks like two eyes glowing out of the darkness and what is seen when it is experienced inwardly, can be projected outwards and experienced in such a way that an entire beyond, an entire world-genesis can be seen in it. Here again an attempt has been made to create out of color what the eye experiences when it looks into the darkness and sees itself. One need not merely read the secrets intellectually, one can see them – suddenly they are there.

In a similar way, attempts were made to bring other motifs into reality, again not from the naturalistic imitation of signs and forms, but entirely from color. The ancient Indians and their inspiration, the seven Rishis, who in turn were inspired by the stars, to paint with an open-topped head (Fig. 32, far right) is, if you do it that way, abstract, actually nonsense; I say that quite openly. But when one experiences what was experienced in the ancient Indian culture in the relationship between the disciple and the guru, the teacher, one feels as if the ancient Indian did not have a skullcap, but as if it had evaporated and as if he were not the one human being who lives in his skin, but one feels as a sevenfold being, as if his soul power was composed of the seven soul rays of the holy Rishis of ancient Atlantis, enlightening him, and that he then communicated to his world that which he revealed, not from his own spirit but from the spirit of the holy Rishis. The more one works out what is said here, the more one comes closer to what has been painted here. The intuitive perception has first placed itself in ancient India, in ancient Atlantis. That which can be seen there has been painted on the wall here, and only afterwards can one speculate when it is there. This is how the message can relate to artistic creation. This is how everything in this building should actually come about.

You will find this building covered with Nordic slate. The building idea must be felt through to the point of radiating outwards. The slate, or the material used to cover it, must shine in a certain way in the sunlight. It seemed to happen by chance here – but of course there is always an inner necessity underlying it. When I saw the Nordic slate in Norway from the train, I knew that it was the right thing to cover the building with. We were then able to have the slate shipped from Norway in the pre-war period. You will feel the effect when you look at the building from a distance in good sunshine.

My main concern during the construction was the acoustics. The building was of course also provided with scaffolding on the inside during construction so that work could be carried out above. This did not produce any acoustics, the acoustics were quite different, that is, it was a caricature of acoustics. Now it so happens that the acoustics of the building were also conceived from the same building idea. My idea was that I had to expect that the acoustic question for the lecturer could be solved from occult research. You know how difficult it is; you cannot calculate the acoustics. You will see how it has been done, but to a certain degree of perfection in the acoustics.

You may now ask how these seven pillars, which contain the secret of the construction, are related to the acoustics. The two domes within our building are so lightly connected that they form a kind of soundboard, just as the soundboard of a violin plays a role in the richness of the sound. Of course, since the whole, both the columns and the dome, are made of wood, the acoustics will only reach perfection over the years, just as the acoustics of a violin only develop over the years. We must first find a way to have a profound effect on the material in order to be able to feel through the building idea what is now sensed as the acoustics of this building. You will understand that the acoustics must be sensed best from the organ podium. You will also see that when two people talk to each other here in the middle, an echo can be heard coming down from the ceiling. This seems to be an indication from the world essence that one should only speak from the stage or the lectern within the building and that the building itself does not actually tolerate useless chatter from any point.

Now, dear attendees, I have tried to tell you what can be said in this regard while looking at the building. I will have to supplement what I have spoken today in my presentation of the building idea, which I will give at the final event next Saturday. Then I will say what can still be said. Now we have to clear the hall for the next lecture.

6. Führung Durch Das Goetheanum

Ich möchte über den Baugedanken einige Worte zu Ihnen sprechen, mit der unterstützenden unmittelbaren Anschauung des Baues. Es könnte von vornherein die Ansicht entstehen, wenn man über einen solchen Bau erst sprechen muss, so weise das darauf hin, dass er als künstlerisches Werk nicht den bei der Kunst notwendigen Eindruck macht; und vielfach wird auch dasjenige, was über den Bau von Dornach, über das Goetheanum in der Welt gedacht wird, von einem durch eine [einseitige] Sinnesanschauung beeinflussten falschen Gesichtspunkt aus gedacht. Man hat zum Beispiel die Meinung verbreitet, der Bau in Dornach wolle allerlei symbolisieren, er sei ein symbolisierender Bau. Sie werden in Wirklichkeit beim Beschauen dieses Baues kein einziges Symbol finden, wie sie beliebt sind in mystischen und theosophischen Gesellschaften. Der Bau soll durchaus aus der ki sehen Empfindung heraus erlebt werden können und ist auch aus diesen künstlerischen Empfindungen heraus in seinen Formen, in all den Einzelheiten, entstanden. Daher muss er auch nur durch das wirken, was er selber ist.

Das Erklären ist ja beliebt geworden, und man kommt dann solchen Erklärungswünschen nach; aber indem ich dies hier vor Ihnen erwähne, sage ich zugleich, dass mir ein solches Erklären eines Künstlerischen immer nur als etwas nicht nur halb, sondern fast ganz Unkünstlerisches erscheint, und dass ich jetzt vor Ihnen eine Art Vortrag halten werde im Angesicht des Baues, einen Vortrag, der mir im tiefsten Grunde unsympathisch ist, schon aus dem Grunde, weil ich über das, was bei Ausgestaltung des Baues, der Modelle und so weiter als Einzelheiten sich mir ergeben hat und was aus dem Leben heraus geschaffen ist, in abstrakten Worten zu Ihnen sprechen muss. Ich möchte lieber möglichst wenig über den Bau zu Ihnen sprechen.

Es ist nun schon einmal so, dass in der Gegenwart eine neue Stilform, eine neue künstlerische Sprechform, mit einem gewissen Misstrauen betrachtet wird. Mir tönt immer wiederum ein Wort noch nachträglich in den Ohren, das ich vor vielen Jahrzehnten hörte, als ich an der Technischen Hochschule [in Wien] studierte, wo Ferstel seine Vorträge hielt. In einem derselben sagt er: «Baustile werden nicht erfunden, ein Baustil wächst heraus aus dem Volkscharakter.» Daher liegt auch im Sinne Ferstels eine Ablehnung jeglicher Erfindung eines gewollten neuen Baustiles, einer neuen Bauart. Wahr ist an diesem Gedanken, dass der Stil, der die Eigenheiten eines Volkes stilisieren soll, hervorgehen muss nicht aus einem Abstrakten, sondern aus einer lebendigen Weltanschauung, die zugleich ein Welterleben ist und von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus umfassend das für die gegenwärtige Menschheit chaotische geistige Gegenwartsleben. Ausgehend von diesem durchaus zutreffenden Gedanken wird es notwendig, dasjenige, was den bisherigen Baustilen eigen war durch das Aufnehmen des Symmetrischen, des Geometrisch-Statischen und so weiter, in organische Bauformen überzuführen.

Ich weiß sehr gut, was von demjenigen, der sich seelisch eingelebt hat in die bisherigen Baustile, vorgebracht werden kann -und von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus mit Recht vorgebracht werden kann - gegen das, was hier in Dornach als Baustil versucht worden ist: die Überführung der geometrisch-symmetrisch-statischen Formen in organische Formen. Aber es wurde einmal versucht. Und so sehen Sie in diesen Bauformen, dass dieser Bau hier ein noch mangelhafter erster Sprechversuch ist zur Überführung dieser geometrischen Bauformen ins Organische. Es ist ja gewiss, dass die Entwicklung der Menschheit zu diesen Bauformen hindrängt, und wenn man wieder die Impulse des hellseherischen Erlebens haben wird, werden diese Bauformen, das glaube ich, die erste, führende Rolle spielen.

Es soll dieser Bau in demselben Sinne durch seine Verwandtschaft mit den organisierenden Kräften der Natur verstanden werden, wie die bisherigen Bauten verstanden werden durch ihre Verwandtschaft mit den geometrisch-statisch-symmetrisierenden Kräften der Natur. Von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus ist dieser Bau zu beschauen, und von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus werden Sie einsehen, wie jede Einzelheit innerhalb des Baugedankens für Dornach hier ganz individualisiert werden muss. Denken Sie nur einmal an Ihr Ohrläppchen: Es ist ein sehr kleines Glied im menschlichen Organismus, aber Sie können sich nicht gut denken, dass eine solche organische Form wie das Ohrläppchen sich dazu eigne, an der großen Zehe zu wachsen. Es ist dieses Organ innerhalb des Organismus durchaus an seinen Ort gebunden. So wie Sie finden, dass innerhalb des ganzen Organismus ein Stützorgan, ein Tragorgan stets so geformt ist, dass es innerhalb des Organismus statisch-dynamisch wirken kann, so mussten auch die einzelnen Formen in unserem Bau in Dornach so sein, dass sie den statischdynamischen Kräften dienen können. Jede einzelne Form musste darauf hinorganisiert werden, dass sie an ihrem Orte dasjenige sein konnte und musste, als was sie jetzt erscheint. Sehen Sie sich von diesem Gesichtspunkte jeden Bogen an, wie er gestaltet ist, wie er sich zum Beispiel abflacht gegenüber dem Ausgang zu, wie er sich in sich rundet gegenüber dem Bau selbst, wo er nicht nur zu stützen, sondern auch das Stützen zum organischen Ausdruck zu bringen hat und dabei das mitzuentwickeln hat, was beim organischen Bilden nur scheinbar ganz unnötig erscheint. Die gewöhnliche Baukunst lässt das über das Statische Hinausgehende weg, was der Organismus ausbildet. Man empfindet aber, wenn der Baugedanke übergeführt ist zur organischen Ausgestaltung der Formen, diese auch als notwendig.

Von diesem Gesichtspunkte werden Sie jede Säule zu betrachten haben; dann werden Sie auch begreifen, dass die gewöhnliche Säule, die aus dem Geometrisch-Statischen herausgeholt ist, ersetzt worden ist durch eine nicht das Organische nachahmende - alles ist so, dass es nicht naturalistisch nachgeahmt ist -, sondern überführt in organisch gemachte Gebilde. Es ist nicht nachgeahmt einem organischen Gebilde. Sie kommen nicht darauf, wenn Sie in der Natur ein Vorbild suchen. Aber Sie kommen darauf, wenn Sie verstehen, wie der Mensch zusammenleben kann mit den Kräften, die organisierend in der Natur wirken, und wie, abgesehen von dem, was die Natur selber schafft, in dieser Weise organisierende Formen entstehen können. So werden Sie in diesen Säulenträgern sehen, wie zugleich zum Ausdruck kommt die Ausweitung des Baues, das Tragen, das Hinweisen nach innen und, in derselben Weise wie etwa, sagen wir im oberen Ende des menschlichen Oberschenkels das Tragen, das Gehen, das Wandeln und so weiter statisch, aber organisch-statisch verkörpert ist.

Von diesem Gesichtspunkt bitte ich auch so etwas zu betrachten wie das Gebilde mit den drei senkrecht aufeinander stehenden Gestaltungen beim Aufgang hier unten an der Treppe (Abb. 23, 24). Es steigt hier die Empfindung auf, wie der Mensch sich fühlt, wenn er die Treppe hinaufstrebt. Er muss ein Gefühl haben von Geborgenheit, von seelischer Geschlossenheit bei alldem, was in diesem Bau vorgeht, ja bei allem, was er in diesem Bau sieht. Alles kam mir ganz aus der Empfindung heraus. Sie mögen es glauben oder nicht, diese Form kam mir ganz aus der künstlerischen Empfindung heraus. Wie gesagt, Sie mögen es glauben oder nicht, erst nachträglich fiel mir ein, dass diese Form etwas erinnert an die Form der drei halbkreisförmigen Zirkel im menschlichen Ohr, die, wenn sie verletzt sind, Ohnmacht erzeugen, sodass sie unmittelbar ausdrücken, was dem Menschen Standfestigkeit gibt. Dieser Ausdruck, dass dem Menschen in diesem Bau Standfestigkeit gegeben werden soll, kommt zustande in dem Erleben der drei senkrecht aufeinander stehenden Richtungen. Das kann an diesem Gebilde durchaus erlebt werden, ohne dass man sich auf ein abstraktes Überlegen einlässt. Man kann durchaus im Künstlerischen bleiben.

Wenn Sie sich in dem Umgang die wandartigen Gebilde anschauen, werden Sie finden, dass auch da natürlich wirkende Kräfte in die Formen hineingegossen sind, aber so, dass bei diesen Formen, die ja Heizkörpervorsätze sind (Abb. 26), zunächst aus dem Betonmaterial des Baues herausgearbeitet ist, weiter oben aus dem Material des Holzes, und dass sie dadurch metamorphosiert sind. Sie werden finden, dass in diesen Gebilden der Prozess der Metamorphose ins Künstlerische hinaufgehoben ist. Es ist der Baugedanke, der durchaus wirken soll bei solchen Heizkörpervorsätzen, die so angelegt sind, dass man unmittelbar den Zweck empfindet und nicht erst gedanklich ihn zu erforschen braucht. Dadurch ergeben sich für die Empfindung diese elementaren Formen, die halb pflanzlich, halb tierisch sind, von denen man erst weiß, dass sie so sein müssen, wenn man sie aus dem Material heraus geformt hat. Und es ergibt sich auch die innere Notwendigkeit, sie zu metamorphosieren, je nachdem sie an dem einen oder dem anderen Orte sind, je nachdem sie lang und niedrig oder schmäler und höher sind. Das alles ergibt sich nicht aus einem Errechnen der Form, sondern die Formen gestalten sich aus der Empfindung heraus selbst in ihrer Metamorphose, wie zum Beispiel hier, wo wir bis jetzt gegangen sind, wo der Bau in seinem Untergeschoss ein Betonbau ist und wo man sich in die Gestaltung dessen, was der Beton ist, hineinzuversetzen hat. Man geht hier zum Westtor herein. Hier ist der Raum zum Ablegen der Garderobe. Über die Treppe, die hier links und rechts emporführt, geht man hinauf in den Holzbau, der den Zuschauerraum, den Bühnenraum und Nebenräume enthält. Sie werden nun so gut sein, mir zu folgen über die Treppe hinauf in den Zuschauerraum.

Wir treten hier zunächst in eine Art Vorraum (Abb. 27). Sie werden hier empfinden den ganz andersartigen Eindruck, den die Holzverkleidung hervorruft gegenüber der Betonverkleidung im Untergeschoss. Hier möchte ich bemerken: Wenn man aus Stein, aus Beton oder aus sonstigem hartem Material baulich zu arbeiten hat, hat man sich anders zu stellen, als wenn man aus weichem Material, zum Beispiel Holz, zu arbeiten hat. Das Holzmaterial macht notwendig, seine ganze Empfindung darauf zu richten, dass man Ecken, Konkaven, Vertiefungen aus dem weichen Material herauszuschaben hat, wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf. Es ist ein Schaben, ein Herausschaben. Man vertieft das Material, und nur dadurch kommt man in diese Verwandtschaft mit dem Material hinein, die eine wirklich künstlerische Verwandtschaft ist. Während man beim Arbeiten mit Holz nur dann dazu kommt, aus dem Material das hervorzulocken, was die Formen gibt, wenn man seine Aufmerksamkeit auf das Vertiefen richtet, hat man es beim Arbeiten mit hartem Material nicht mit den Vertiefungen zu tun. In eine Verwandtschaft mit dem harten Material kommt man nur dadurch, dass man aufträgt, dass man konvex arbeitet, Erhabenheiten aufträgt auf die Grundflächen, zum Beispiel, wenn man mit Gestein arbeitet. Dies zu erfassen ist ein Wesentliches im künstlerischen Schaffen, und es ist dies zum Teil in der neueren Zeit verlorengegangen.

Sie werden sehen, wenn wir in den Zuschauerraum kommen, wie da jede einzelne Fläche, jedes Kapitel für sich individuell behandelt ist. Ein Kapitell kann in diesem organischen Bau nur so sein, dass man an ihm empfindet: In dem, was einander folgt, kann nicht eine Art von Wiederholungen geschaffen werden, wie das sonst bei symmetrisch-geometrisch-statischen Baustilen der Fall ist, Sie haben in diesem Bau aus dem organischen Gedanken heraus nur eine einzige Symmerrieachse, die von West nach Ost geht. Nur in Bezug auf diese finden Sie eine symmetrische Anordnung, wie Sie auch für einen höheren Organismus nur eine einzige Symmetrieachse finden können, nicht aus einer Willkür heraus, sondern aus der inneren Kräfte-Organisation der betreffenden Wesenheit heraus.

Hier an dieser Stelle möchte ich noch erwähnen, dass auch die Wandbehandlung unter dem Einflusse des organischen Baugedankens eine ganz andere werden musste, als sie früher war. Eine Wand war für frühere Architekten das, was einen Raum abgrenzt. Sie wirkte so, dass man im Raum drinnen war. Von dieser Empfindung musste abgegangen werden bei diesem Bau. Die Wände mussten so gestaltet werden, dass man sie nicht als Begrenzung empfand, sondern als etwas, was einen hinausträgt in die Weiten des Makrokosmos; man muss sich empfinden als aufgenommen, als drinnenstehend in den Weiten des Kosmos. Wände mussten gewissermaßen durchsichtig gestaltet werden, während früher alle Sorgfalt darauf verwendet worden ist, der Wand künstlich solche Formen zu geben, dass sie abgeschlossen, undurchsichtig ist. Sie werden sehen, dass das Durchsichtige überhaupt künstlerisch gebraucht wird, und das wurde aus elementaren Untergründen heraus bis ins Physische hineingetrieben bei diesen Fenstern, die Sie hier sehen und die Sie im Bau sehen werden.

Wenn Sie Fenster sehen im Sinne des früheren Baustiles, so werden Sie eigentlich die gesunde Empfindung haben müssen: Sie durchbrechen die Wände, sie gliedern sich nicht ein in die Bauformen, sondern sie gliedern sich nur ein durch das Utilitätsprinzip. Hier wird bis in die Einzelheiten hinein künstlerisch empfunden werden müssen. Es war die Notwendigkeit vorhanden, die Wand so darzustellen, dass sie nicht etwas Abschließendes, sondern etwas nach außen, nach dem Unendlichen sich Weitendes ist. Das konnte ich nur dadurch erreichen, dass mir einfiel, dass man aus einfarbigen Fensterscheiben gewissermaßen wie durch eine Radiermethode, eine Glasradiermethode, Gestaltungen herauskratzen kann. Und so wurden einfarbige Fensterscheiben angeschafft, welche dann so bearbeitet wurden, dass die Motive, die man haben wollte, mit dem Diamant-Stift herausgekratzt wurden. Es wurde also zu diesem Zwecke eine eigentliche Glasradierkunst ins Auge gefasst, und aus dieser heraus sind die Fenster entstanden.

Wenn Sie die Motive der Fenster ins Auge fassen, dürfen Sie nicht denken, man habe es bloß mit symbolischem Gestalten zu tun. Sie können es schon an dieser größeren Wandfensterscheibe (Abb. 109) sehen: Nichts anderes ist an diesen Fensterscheiben gestaltet, als was die Imagination ergibt. Es gibt Mystiker, die eine Mystik mit oberflächlichen Sentenzen und merkwürdigen Vorstellungen ausbilden und fortwährend erklären, dass die physisch-sinnliche Außenwelt eine Art Maja, Illusion sei. Oft treten Menschen an einen heran und sagen, der und der sei ein großer Mystiker, weil er immer deklamiert, dass die Außenwelt eine Maja sei. - Das physische Menschenantlitz hat etwas, was Maja, was durchaus Lüge ist, was in Wahrheit etwas anderes ist. Das auf dieser Wandfensterscheibe zutage Tretende ist nicht etwas Symbolisierendes; es ist ein Wesen ins Auge gefasst, das nur nicht so aussieht für den geistigen Betrachter, wie es äußerlich für die Sinnesanschauung aussieht. Der Kehlkopf ist das Bildeorgan für Ätherisches; der Kehlkopf ist als physischer Kehlkopf schon Maja, und dasjenige, was eine bloß physisch-sinnliche Anschauung ist, ist nicht Wirklichkeit.

Was steht geistig dahinter? Die geistige Tatsache, dass dem Menschen wirklich ins Ohr geraunt wird, links und rechts, was Weltengeheimnisse sind. Sodass man schon sagen kann: Der Stier spricht ins linke Ohr, der Löwe ins rechte Ohr. Will man so etwas als Motiv im Bild darstellen oder in Worten, so kann man in das Wort nur dasselbe hineinlegen, was schon im Bilde selbst ist. Allerdings muss man sich klar sein, dass man ein solches Bild nur verstehen kann, wenn man in dieser Weltanschauung lebt, aus der es hervorgegangen ist. Ein Mensch, der nicht lebendig in christlichem Empfinden steht, wird sich auch nicht verständnisvoll verhalten können gegenüber den Bilddarstellungen, wie sie die christliche Kunst hervorgebracht hat.

Der Künstler durchlebt viel, wenn er sich in eine Schauung hineinlebt; aber ein solches Erlebnis darf nicht in abstrakte Gedanken übergeführt werden, sonst fängt es sogleich an zu verblassen. Ein Beispiel für das Erleben des Künstlers ist dieses: Als Leonardo da Vinci sein Abendmahl malte, das nun schon so verfallen ist, dass es künstlerisch nicht mehr genossen werden kann, da dauerte das den Leuten zu lange. Er wurde mit dem Judas nicht fertig, weil dieser Judas aus der Dunkelheit hervorgehen sollte. Leonardo arbeitete bald zwanzig Jahre an diesem Bild und war noch nicht fertig. Da kam ein neuer Prior nach Mailand und sah sich die Arbeit an. Er war kein Künstler; er sagte, Leonardo, dieser Diener der Kirche, müsse endlich einmal sein Werk zu Ende schustern. Da antwortete Leonardo, jetzt könne er dies auch tun; er habe bisher immer an der Figur des Judas herumgestrichelt, weil er das Modell dazu nicht gefunden habe; jetzt sei der Prior da, in ihm habe er das Modell zu dem Judas gefunden, jetzt werde das Bild schnell zu Ende geführt werden. — Da haben Sie ein solches äußeres, konkretes Erlebnis. Solche äußeren, konkreten Erlebnisse spielen viel mehr in alles Schaffen des Künstlers hinein, als das in solchen kurzen Darstellungen zu Wort kommen kann.

Sie sind [nun] hier, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, durch den Raum unterhalb der Orgel und den Raum für die Musikinstrumente in den Bau eingetreten. Wenn Sie, nachdem Sie eingetreten sind, sich rundherum umsehen, so finden Sie den Baugedanken zunächst dadurch charakterisiert, dass der Grundriss (Abb. 20) zwei nicht ganz vollendete Kreise darstellt, die in ihren Segmenten ineinandergreifen. Mir scheint, dass die Notwendigkeit, den Bau so zu formen, schon ersichtlich werden kann, wenn man sich dem Bau von einer gewissen Entfernung her nähert und wenn man eine Ahnung hat von dem, was in dem Bau eigentlich vorgehen soll. Das, was mit dem Baugedanken zusammenhängt, will ich jetzt weiter ausführen. Zunächst will ich darauf hinweisen, dass Sie in Symmetrie einzig und allein gegen die WestOst-Achse angeordnet, im Fortschreiten links und rechts den Zuschauerraum abschließend, sieben Säulen sehen. Diese sieben Säulen sind nicht so gebildet, dass sich eine Kapitellform, eine Sockelform oder eine darüber befindliche Architravform wiederholt, sondern die Kapitell-, Sockel- und Architravformen sind in durchaus fortschreitender Entwicklung. Die zwei Säulen, die hinten den Orgelraum abgrenzen, haben die einfachsten Kapitell- und Sockelmotive (Abb. 28, 33): Formen, die gewissermaßen von oben nach unten streben, denen andere von unten nach oben entgegenstreben. Diese noch primitivste Form des Ineinanderwirkens von oben und unten ist dann metamorphosiert in den folgenden Architrav-, Kapitell- und Sockelformen (Abb. 35-54).

Dadurch ist künstlerisch empfindend diese fortschreitende Metamorphose zustande gekommen, dass versucht wurde, als ich das Modell (Abb. 22) ausbildete, dasjenige, was in der Natur kraftet, nachzugestalten. Was in der Natur kraftet, indem an der Pflanze zuerst unten ein ungekerbtes Blatt mit primitiven Formen gebildet wird, dann sich dieses Primitive metamorphosiert, je weiter man nach oben geht, zu dem gegliederten, eingebuchteten, komplizierter gestalteten Blatt, sogar umgestaltet zum Blumenblatt, zu Staubgefäßen und Stempel, das muss man - allerdings nicht in naturalistischer Weise - nachahmen, in das muss man sich selber ganz innerlich lebendig hineinstellen und dann ebenso aus sich heraus schaffen, wie die Natur schafft und umgestaltet, wie sie produziert und metamorphosiert. Dann bekommt man, ohne nachzusinnen, aus viel tieferen Seelenkräften heraus als aus dem Nachdenken, solche Umgestaltungen des Zweiten aus dem Ersten, des Dritten aus dem Zweiten und so weiter.

Missverstanden kann werden, dass zum Beispiel bei der fünften Säule und an den Architravmotiven über der vierten Säule so etwas auftritt wie eine Art Merkurstab (Abb. 41, 42). Man könnte nun glauben, dass der Merkurstab aus dem Verstande heraus an diese beiden Stellen hingepfahlt worden sei. Ich glaube, wer aus dem Verstande heraus gearbeitet hätte, hätte wahrscheinlich im Architravmotiv den Merkurstab angebracht und darunter - der Verstand wirkt symmetrisierend - auch das Säulenmotiv mit dem Merkurstab. Derjenige, der so arbeitet, wie hier gearbeitet worden ist, findet anderes. Hier bei dem Motiv, das Sie als das vierte Kapitellmotiv sehen, ist nur durch Empfinden der metamorphosierenden Umwandlung, ohne dass ich dabei im Entferntesten einen Merkurstab zu bilden gedachte, dieser Merkurstab so hervorgegangen, wie das Blütenblatt aus dem Kelchblatt hervorgeht. Nicht dachte ich an einen vergangenen Stil, sondern an die Umwandlung des vierten Kapitellmotivs aus dem dritten. Man sieht, wie die Formen, die in der Entwicklung der Menschheit allmählich aufgetreten sind, sich ganz naturgemäß entwickelt haben.

Dann kommt man in die Epoche, wo der Mensch mit seinem Seelenleben in die Entwicklung eingreift. Wenn man dies in die Säule individualisierend hineinarbeitet, so ergibt sich das später, was sich auf dieser Architravfläche arbeitend früher ergibt. Deshalb sehen Sie auf dem Kapitell den Merkurstab später als auf dem Architrav. Eine Pflanze, die dünn und zierlich ist, entwickelt andere Blattformen als eine derbe. Vergleichen Sie nur ein Hirtentäschel mit einem Kaktus, wie da die Raumausfüllung, die Raumgestaltung in der figürlichen Gestaltung zum Ausdruck kommt.

Gleichzeitig ergibt sich ein Weltengeheimnis darin, indem man so die Evolution durchempfindet. Von Evolution wird ja in neuerer Zeit viel geredet, aber man empfindet wenig dabei. Man denkt es nur aus mit dem Verstande. Man spricht so von der Evolution des Vollkommenen aus dem Unvollkommenen. Herbert Spencer und andere haben dazu noch das nötige und unnötige Unheil angerichtet, und da ist der Gedanke entstanden, der vor dem Verstande vollständig berechtigt ist, der aber doch der Naturbeobachtung nicht gerecht wird: Man geht beim Verstandesdenken davon aus, dass in der Evolution im Anfang die einfacheren Formen stehen und dass diese dann später immer differenzierter und differenzierter werden. Insbesondere Spencer hat mit solchen Evolutionsgedanken gearbeitet. Aber die Evolution zeigt das nicht so. Da findet allerdings zuerst eine Differenzierung, eine Komplizierung der Formen statt; dann aber kommt man zu einer Mitte, und dann vereinfachen sich die Formen wieder. Das Folgende ist nicht das Kompliziertere, sondern das Folgende wird wieder einfacher. Man kann das in der Natur selber verfolgen. Das menschliche Auge, das das vollkommenste ist, hat es gewissermaßen zu größerer Einfachheit gebracht als die Augenformen gewisser Tiere, die zum Beispiel den Schwertfortsatz, den Fächer haben, der wieder verschwunden ist, indem das Auge in der Evolution weiter heraufrückte zum Menschen.

So ist es notwendig, dass der Mensch sich mit der Kraft der Natur verbindet, dass er die Kraft der Natur empfindet, dass er die Kraft der Natur zu seiner eigenen Kraft macht und aus dieser Empfindung heraus schafft. So ist versucht worden, auch in der Innenarchitektur diesen Bau durchaus organisch zu gestalten, jede Einzelheit an ihrem Orte so zu gestalten, wie sie aus dem Ganzen heraus individualisiert sein muss. So sehen Sie, dass zum Beispiel die Orgel (Abb. 28-30) von plastischen Motiven umgeben ist, die [es so] erscheinen lassen, dass die Orgel nicht einfach hineingestellt ist, sondern dass sie aus der ganzen übrigen Gestaltung des Organischen heraus wirkt wie aus ihm herauswachsend. So muss alles dasjenige zu machen versucht werden, was in diesem Bau ist.

Sie sehen hier das Rednerpult (Abb. 68), auf dem ich stehe. Bei ihm kam zunächst in Betracht, an dieser Stelle etwas zu schaffen, was gewissermaßen herauswächst aus den übrigen Bauformen, aber so, dass es zu gleicher Zeit zum Ausdruck bringt, dass man sich von hier aus anstrengt, alles, was im Bau zum Ausdruck kommen soll, durch das Wort auszudrücken. Es müssen in dem Moment, wo ein Mensch hier spricht, die Formen des Gesprochenen sich so fortsetzen, wie etwa die Nase im Antlitz durch ihre Form verrät, was der ganze Mensch ist. Derjenige, der künstlerisch inspirierte Nasenstudien gemacht hat, kann aus einer Nasenstudie den «Baustil», die Physiognomie des ganzen Menschen machen. Es kann der Mensch niemals eine andere Nase haben, als er hat, und es könnte hier niemals ein anderes Rednerpult stehen als das, das hier steht. Allerdings, wenn man dies behauptet, ist es so nach der eigenen Anschauung gemeint; man kann nur nach der eigenen Anschauung handeln.

Dass hier versucht worden ist, wirklich den Leib zu metamorphosieren, können Sie daraus ersehen, dass die Motive hier in den Glasfenstern zum Teil wirklich solche Motive sind, die sich ergeben als Bilder des Seelenlebens. Sehen Sie zum Beispiel das rosafarbige Fenster hier an (Abb. 113). Sie werden an dem linken Flügel sehen, wie da etwas herauskommt wie das Westportal des Baues; am rechten Flügel sehen Sie eine Art Kopf. Da sehen Sie einen Menschen am Abhang sitzen, der nach dem Bau hinblickt, und einen anderen, der nach dem Kopf hinblickt. Damit ist nichts spekulativ Mystisches gemeint, damit ist ein unmittelbares inneres Anschauungserlebnis gemeint. Dieser Bau hat nicht anders entstehen können, als dass man die Kopfform des Menschen in einer geheimnisvollen Weise darin empfand, und aus der organischen Kraft einerseits und der Form des menschlichen Hauptes andererseits ergibt sich die empfindungsgemäße Gestalt der Bauform. Daher schaut der an dem Abhange sitzende Mensch in seiner Seele die Metamorphose des Baues an, einmal als menschliches Haupt, das andere Mal den Bau als sich nach außen offenbarend. Damit ist ein, wenn ich so sagen darf, in ein inneres Erleben einmündendes Motiv gegeben.

Sie finden dort in der blauen Fensterscheibe (Abb. 111) einen Menschen, welcher - links anlegt, um einen Vogel in der Luft zu schießen. In der rechten Scheibe finden Sie, dass der Mensch abgedrückt hat. Der Vogel im linken Felde ist in einer Lichtsphäre. Um den Menschen herum finden Sie allerlei Gestalten, die [in] dem astralischen Leibe anschaulich leben, das eine Mal, wenn er schießen will, das andere Mal, wenn er geschossen hat. Eine Realität ist dies, allerdings eine aus dem profanen Leben. Ich kann mir vorstellen, dass diejenigen, die stets von innerlicher Erhebung nur so triefen möchten, Anstoß daran nehmen, wenn sie solche Dinge, wie sie hier gemeint sind, so erleben, dass einfach ein menschliches Schießen dargestellt ist. Ja, da freute es mich, als einmal eine italienische Freundin über Theosophen, die solche Mystiker sind, einen etwas derben Ausdruck gebraucht hat. Die bereits gestorbene Freundin sagte es, und ich darf es in der sehr hochgeschätzten Gesellschaft hier schon sagen, denn die Betreffende war eine Prinzessin, und was eine Prinzessin in den Mund nimmt, das kann man schon auch sagen. Sie glossierte solche Menschen, die immer in einer Art innerer Erhebung leben möchten, indem sie sagte, dass sie Menschen seien mit einem «Gesicht bis ans Bauch». Ich wiederhole auch ihr nicht ganz korrektes Deutsch.

Nun, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, derselbe Gedanke wurde dann auch durchgeführt in der Malerei. Ich kann über das eigentliche Malerische, über die geistige Malerei nur sprechen, indem ich mich auf die kleine Kuppel beziehe. Nur in der kleinen Kuppel war es mir möglich, dasjenige durchzuführen, was ich angedeutet habe als die Forderung einer neueren Malerei: dass hier hinter dem Herausschaffen aus dem Farberleben das Zeichnen ganz verschwindet. Ich ließ eine meiner Personen im ersten Mysteriendrama dies so aussprechen: dass die Formen als der Farbe Werk erscheinen. - Denn wenn man mit malerischem Empfinden fühlt, dann fühlt man das Zeichnerische, das in Malerisches hineingetragen ist, wie eine Lüge. Wenn ich die Horizontallinie hinzeichne, so ist das eigentlich eine Wiedergabe von etwas, was gar nicht da ist. Wenn ich den blauen Himmel als eine Fläche auftrage und unten das Grüne, dann ergibt sich die Form aus dem Erleben des Farbigen selber. So kann jedes Malerische gestaltet werden. Innerhalb der Farbenwelt selber liegt eine schöpferische Welt, und derjenige, der die Farben empfindet, malt, was die Farben sich gegenseitig sagen im Schaffen. Er braucht an kein naturalistisches Modell sich zu halten, er kann aus den Farben selber die Figuren schaffen. Es ist so, dass die Natur und auch das Menschenleben schon ein gewisses Recht haben, mit einer Notwendigkeit aus dem Farbigen heraus nun das Sittliche zu gestalten.

Mit großer Berechtigung hat gestern Herr Uehli darauf hingewiesen, wie neuere Maler an sich schon eine Empfindung haben von solcher Herauswirkung aus dem Helldunkel, aus dem Farbigen selbst, und wie diese dazu kommen, eine Bassgeige neben einer Konservenbüchse zu malen. Sie verfolgen dabei an sich das Richtige, dass es nur mehr darauf ankommt zu sehen, wie sich das Licht abstuft in seinem Farbigwerden, wenn es auf eine Bassgeige fällt und dann weiterhin fällt auf eine Konservenbüchse. Das ist das Richtige. Aber das Unrichtige ist doch, dass das wieder auf dem naturalistischen Erleben ausgetragen wird. Wenn man sich wirklich in das Farbige hineinlebt, ergibt sich aus dem Farbigen heraus etwas anderes als eine Konservenbüchse und eine Bassgeige. Das Farbige ist schöpferisch, und wie sich das zusammenstellt, ergibt doch eine Notwendigkeit aus dem bloßen Farbigen heraus, die man erleben muss. Dann macht man nicht eine Konservenbüchse neben eine Bassgeige, weil das doch wieder außerhalb des Farbigen ist.

So ist hier versucht worden, ganz aus dem Farbigen heraus zu malen. Wenn Sie hier neben dem blauen Fleck den rötlich-orangen Fleck sehen und den schwarzen Fleck, so ist dies zunächst aus dem Farbigen heraus lebendig empfunden. Dann aber kommen die Farben ins Leben, dann werden Figuren daraus, die man nachträglich sogar deuten kann. Aber ebenso wenig, wie man hierher mit dem menschlichen Verstande Pflanzen machen kann, ebenso wenig kann man etwas darauf malen, was man mit dem menschlichen Verstande ausgedacht hat. Man muss erst dann denken, wenn die Farben da sind, ebenso wie die Pflanze erst wachsen muss, che man sie sehen kann.

So ist da eine Faust-Figur mit dem Tod und dem Kinde entstanden (Abb. 69-74). So ist der ganze Kopf aus dem Farbigen heraus mit allem Figürlichen entstanden. Nur im Menschlich-Seelischen bildet sich von selber ein geistig reales Gegenständliches. So sehen Sie zum Beispiel über dem Orgelmotiv, wie etwas gemalt ist (Abb. 31), was ein banausisch an der Sinnenwelt haftender Mensch natürlich wie eine Verrücktheit empfinden wird. Aber Sie werden es nicht mehr als Verrücktheit empfinden, wenn ich Ihnen das Folgende sage: Wenn Sie Ihre Augen zudrücken, so werden Sie gewissermaßen, das Innere des Auges erfühlend, etwas wie zwei sich anblickende Augen sehen. Das, was da innerlich sich abspielt, kann durchaus in gewisser Weise weiterentwickelt werden. Dann gestaltet sich das, was, in primitiver Weise betrachtet, wie zwei Augen aus dem Dunkel einem entgegenleuchtet und was das innerlich erlebte sehen ist, so, dass es - wenn es sich hinausprojiziert - so erlebt werden kann, dass man ein ganzes Jenseits, eine ganze Weltentstehung darin sieht. Da ist wiederum aus dem Farbigen heraus zu schaffen versucht worden, was das Auge erlebt, wenn es durch Zudrücken sein Selbst im Dunkel schaut. Man braucht nicht nur aus dem Verstande heraus die Geheimnisse zu lesen, man kann sie schauen - plötzlich sind sie da.

In ähnlicher Weise ist versucht worden, andere Motive in die Wirklichkeit zu bringen, wiederum nicht aus dem naturalistischen Nachahmen der Zeichen und Formen, sondern ganz aus der Farbe heraus. Die alten Inder und ihre Inspiratoren, die sieben Rishis, die wiederum inspiriert sind von den Sternen, mit nach oben offenem Kopfe zu malen (Abb. 32, ganz rechts), das ist, wenn man das jetzt so tut, abstrakt, eigentlich ein Nonsens; ich sage das ganz offen. Wenn man aber erlebt, was in der urindischen Kultur erlebt worden ist in dem Verhältnis des Schülers zu dem Guru, dem Lehrer, so empfindet man dies, wie wenn der alte indische Mensch nicht eine Schädeldecke gehabt hätte, sondern wie wenn sich diese verflüchtigte und wie wenn er nicht der eine Mensch wäre, der in seiner Haut lebt, sondern man empfindet ihn als eine Siebenheit, es ist, wie wenn seine Seelenkraft aus den sieben gewissermaßen Seelenstrahlen der heiligen Rishis - aus der alten Atlantis herüber, ihn erleuchtend- sich zusammensetzte, und dass er dieses, was er also nicht aus seinem, sondern aus dem Geiste der heiligen Rishis heraus offenbart, dann seiner Welt mitteilte. Je mehr man heraus arbeitet, was hier gesagt ist, desto mehr kommt man dem näher, was hier gemalt worden ist. Die Empfindung hat sich zunächst versetzt in das alte Indien, in die alte Atlantis. Das, was da geschaut werden kann, ist hier an die Wand gemalt worden, und erst nachträglich kann man spekulieren, wenn es da ist. So kann sich die Mitteilung zum künstlerischen Schaffen verhalten. So soll eigentlich alles in diesem Bau entstehen.

Sie werden diesen Bau gedeckt finden mit nordischem Schiefer. Der Baugedanke muss durchgefühlt werden bis zu der Wirkungskraft, die nach außen hinstrahlt. Der Schiefer oder überhaupt das eindeckende Material muss im Sonnenlicht in einer gewissen Weise erglänzen. Es ergab sich hier scheinbar zufällig - natürlich liegt immer eine innere Notwendigkeit zugrunde. Als ich in Norwegen von der Eisenbahn aus den nordischen Schiefer sah, wusste ich, dass das das Richtige war zum Eindecken des Baues. Wir konnten dann noch in der Vorkriegszeit den Schiefer von Norwegen herkommen lassen. Sie werden die Wirkung schon empfinden, wenn Sie einmal bei gutem Sonnenschein von einiger Entfernung her den Blick auf den Bau richten.

Meine besondere Sorge, während der Bau gebaut wurde, war die Akustik. Der Bau war selbstverständlich während des Bauens auch innen mit einem Gerüst versehen, damit man oben arbeiten konnte. Das ergab keine Akustik, da war die Akustik eine ganz andere, das heißt, sie war eine Karikatur von einer Akustik. Nun ist es ja so, dass auch die Akustik des Baues aus demselben Baugedanken heraus empfunden wurde. Meine Vorstellung bestand darin, dass ich erwarten musste, dass die akustische Frage aus der okkulten Forschung heraus für den Vortragenden gelöst werden kann. Sie wissen, wie schwierig es ist; man kann die Akustik nicht errechnen, Sie werden sehen, wie es gelungen ist, doch bis zu einer gewissen Vollkommenheit die Akustik durchzuführen.

Sie können nun fragen, wie diese sieben Säulen, die das Geheimnis des Baues enthalten, mit der Akustik zusammenhängen. Die zwei Kuppeln innerhalb unseres Baues sind so leicht miteinander verbunden, dass sie eine Art Resonanzboden bilden, so wie bei der Violine der Resonanzboden eine Rolle für die Tonfülle spielt. Natürlich, da das Ganze, sowohl die Säulen als auch die Kuppel, aus Holz sind, wird sich die Akustik in ihrer Vollkommenheit erst mit den Jahren ergeben, wie sich ja auch die Akustik einer Geige erst mit den Jahren ergibt. Wir müssen erst die Möglichkeit finden, in die Materie durchgreifend einzuwirken, um das, was jetzt vorempfunden wird als die Akustik dieses Baues, im Baugedanken durchempfinden zu können. Sie werden verstehen, dass die Akustik am besten empfunden werden muss vom Orgelpodium. Sie werden auch sehen, dass, wenn zwei hier in der Mitte miteinander sprechen, dann ein Echo von der Decke herab hörbar ist. Das scheint eine Hindeutung aus der Weltwesenheit heraus zu sein, dass hier innerhalb des Baues nur von der Bühne oder dem Rednerpult aus gesprochen werden darf und dass der Bau von seiner eigenen Wesenheit aus das unnütze Schwatzen von irgendeiner Stelle aus eigentlich nicht duldet.

Nun, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, habe ich versucht, Ihnen während des Anschauens des Baues zu sagen, was zunächst in dieser Beziehung zu sagen möglich ist. Ich werde das, was ich heute gesprochen habe, zu ergänzen haben in meiner Darstellung des Baugedankens, die ich bei der Schlussveranstaltung am nächsten Sonnabend geben will. Da wird dann zu sagen sein, was noch gesagt werden kann. Jetzt müssen wir den Saal frei machen für den nächsten Vortrag.