The Building Concept of the Goetheanum

GA 289

29 June 1921, Bern

Automated Translation

5. The Goetheanum as a center for spiritual science

In recent years, anthroposophical spiritual science has found an external center for its work in Dornach, near Basel. The creation of this center, called the Goetheanum, the School of Spiritual Science, was the result of the expansion of anthroposophical spiritual science. After many years of me and others spreading this spiritual science in the most diverse states and places, initially in an ideal form through lectures or similar, around 1909 or 1910 the inner necessity arose to bring to the souls of our fellow human beings what is meant by this spiritual science by means of other means of revelation and communication than those of mere thoughts and words. And so it came about that a series of mystery dramas were performed, initially in Munich. These were written by me and were intended to present in pictorial, scenic form the subject matter that anthroposophical spiritual science must speak of in its entirety.

We have been accustomed throughout the entire course of education in the civilized world over the last three to four centuries to seek knowledge primarily through external sensory observation and by applying the human intellect to this external sensory observation. And basically, all our newer sciences, insofar as they are still viable today, have come about through the effects of the results of sensory observation with intellectual work. After all, the historical sciences do not come about in any other way today either. Intellectualism is the one thing the modern world has confidence in when it comes to knowledge. Intellectualism is the one thing that people have become more and more accustomed to.

And so, of course, people have increasingly come to believe that all the results of knowledge that come before the world can be completely revealed through intellectual communication. Indeed, there are epistemological and other scientific disputes in which it is apparently proven that something can only be valid before the cognitive conscience of contemporary people if it can be justified intellectually. That which cannot be clothed in logical-ideational intellectual forms is not accepted as knowledge. Spiritual science, which really did not want to stop at what is rightly asserted in science as the limits of scientific knowledge, and which wants to penetrate beyond these limits of knowledge, had to become more and more aware that the intellectual way of communicating could not be the only way. For one can prove for a long time with all possible sham reasons that one must imprint all knowledge in intellectual form if it is to satisfy people; one can prove this for a long time

prove it and back it up with spurious reasons – if the world is such that it cannot be expressed in mere concepts or ideas, that it must be expressed through images, for example, if you want to know the laws of human development, then you have to get at something other than the presentation through the word in the theoretical lecture; you have to move on to other forms of presentation than the presentation in intellectual forms.

And so I felt the necessity to express that which is fully alive, namely in the development of humanity, not only in theory through the word, but also through the scenic image. And so my four mystery dramas came into being, which were initially performed in ordinary theaters. This was, so to speak, the first step towards a broader presentation of that which actually wants to reveal itself through this anthroposophical spiritual science, as it is meant here, through the cause of spiritual science itself.

Not in my own case – I may say that without hesitation – but in the case of friends of our cause, the idea arose in the course of this development, which made an external, theatrical presentation necessary, to prepare a place of our own for the work of this spiritual science. And after many attempts to found such a place here and there, we finally ended up on the Dornach hill near Basel, where we received a piece of land for this purpose from our friend Dr. Emil Grosheintz, and we were able to build this ach Hill, we were able to establish this School of Spiritual Science, which is also intended to be a house for presenting the other types of revelation of what is to come to light through this spiritual science; this School of Spiritual Science, which we call the “Goetheanum” today.

Now, if some association or other had set about creating such a framework, such a house, such an architecture, prompted by the circumstances, what would have happened? They would have turned to this or that architect, who might then, without feeling or sensing anything very intensely and without recognizing the content of our spiritual science, have erected a building in the antique or Gothic or Renaissance style or in some other style, and they would have handed down in such a building, which would have been built out of quite different cultural presuppositions, the content of spiritual science in the most diverse fields. This could well have happened with many other endeavors of the present time and would undoubtedly have happened. However, this could not happen with anthroposophically oriented spiritual science.

When we opened our first series of courses on a wide range of subjects at the School of Spiritual Science in Dornach last year, I was able to speak of how, through this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, not only what is science in the narrower sense is to come before humanity, how this spiritual not only draws from the achievements of human sensory observation and the human intellect, but draws from the whole, from the fullness of humanity, and draws from the sources from which religion on the one hand and art on the other also emerge.

This spiritual science does not want to create an abstract, symbolic or a straw-like allegorical art, which merely forces the didactic into external forms. No, that is absolutely not the case. Rather, what is expressed through this spiritual science can work through the word, can shape itself through the word. Spiritual processes and spiritual beings in the supersensible world can be spoken of by resorting to ideas and the means of expressing ideas, to words. But that which stands behind it, which wants to reveal itself in this way, is much richer than what can enter into the word, into the idea, pushes into the form, into the image, becomes art by itself, real art, not an allegorical or symbolic expression. This is not what is meant when we speak of Dornach art.

When Dornach art is mentioned, it is first of all a reference to the original source from which human existence and world existence bubble forth. What one experiences in this original source, when one gains access to it in the way often described here, can be clothed in words, shaped into ideas, but it can also be allowed to flow directly into artistic expression, without expressing these ideas allegorically or symbolically. That which can live in art or, as I could expand on but need not today, in religion, is an entirely identical expression of that which can be given in an idealized representation. This anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is thus predisposed from the outset to flow as a stream from a source from which art and religion can also flow in their original form. What we mean in Dornach when we speak of religious feeling is not just a science made into a religion, but the source of elementary religious power, and what we mean by art is, in turn, also an elementary artistic creation.

Therefore, when some visitors to the Goetheanum or especially those who only hear about it defame our Dornach building and say that one finds this or that allegorical, symbolic representation there, it is simply defamation. There is not a single symbol in the entire Dornach building. Everything that is depicted has been incorporated into the artistic form, is directly sensed. And basically, I always feel somewhat as if I am merely presenting a surrogate when I am expected to explain the Dornach building in words. Of course, if one speaks outside of Dornach, one can make statements about it as one might speak about chapters of art history, for example. But when one sees the building in Dornach itself, I always feel that it is something surrogate-like, if one is also supposed to explain it. This explanation is actually only necessary to convey to people the special kind of language of world view, but the Dornach building has flowed out of it just as, let us say, the Sistine Madonna has flowed out of the Christian world view, without anything being symbolized, but only in such a way that the artist has truly lived in accordance with his feelings, his ideas.

Hamerling, the Austrian poet, was also reproached for using symbolism after he wrote his “Ahasver”. He then rightly replied to his critics: What else can one do when one portrays Nero quite vividly, as a fully-fledged human being, rather than as the symbol of cruelty! For history itself has portrayed Nero as a symbol of cruelty, and there is no mistake in giving the impression of the true, real symbol of cruelty when Nero is portrayed as a living being. At most, there could be an artistic defect in presenting some straw allegory instead of a living entity. Even if the world depicted in Dornach is the supersensible world, it is the supersensible reality that is portrayed. It is not something that seeks to symbolically or allegorically implement concepts. This is the underlying reality, and at the same time it indicates why a house could not be placed here in any old way for this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Any architectural style would have been something external to it, because it is not mere theory, it is life in all fields and was able to create its own architectural style.

Of course, one can perhaps draw a historical line retrospectively by characterizing the essence of ancient architecture in terms of its load-bearing and supporting function, then moving on to the Gothic period and showing how architecture there moves beyond mere load-bearing and supporting, and how the buttress is freed from mere load-bearing and supporting by the pointed arch and the cross-ribbed vault, how a kind of transition to the living is found. In Dornach, however, an attempt has been made to develop this life to such an extent that the pure dynamic, metric and symmetrical of earlier forms of building have been truly transferred into the organic.

I am well aware of how much can be written from the point of view of ancient architecture against this allowing of the geometric, metric, symmetrical forms to be transformed into organic forms, into forms that are otherwise found in organic beings. But nothing is naturalistically modeled on any organisms; rather, it is only an attempt to immerse oneself in the organically creative principle of nature. Just as one can become familiarized with the bearing and supporting when the columns are covered by the crossbeams, and with the entire configuration of the Gothic style in the buttresses, in the ribbed vaulting and so on, so one can also familiarize oneself with the inner forms, the forming of nature that is present in the creation of the organic. If one can find one's way into this, then one does not arrive at a naturalistic reproduction of this or that surface form found in the organic, but one arrives at finding surfaces from what one has directly represented architecturally, which are integrated into the whole structure in the same way that, say, the individual surface on a finger is integrated into the whole human organism.

This is therefore the basic feeling that can be gained from the Dornach building, to the extent that this has been achieved in the first attempt at this new architectural style. What has been striven for is perhaps best expressed as follows: In relation to the smallest detail, the greatest formal context is conceived in such a way that each thing is, at the place where it is situated, as it must be. You need only think, for example, of the earlobe on your own body. This earlobe is a very small organ. If you understand the whole organism, you will say to yourself: the earlobe could not be any different than it is; the earlobe cannot be a little toe, it cannot be a right thumb, but in the organism, everything is in its place, and everything in its place is as it emerges from this organism.

This has been attempted in Dornach. The entire structure, the entire architecture, is conceived as part of a whole, and each individual part is formed in its own place in such a way that it is exactly what is needed at that place. Although there are many objections that could be raised, the attempt has been made, as I said, to make the transition from mere geometric-mechanical construction to building in organic forms. As I said, this architectural style could be incorporated into other architectural styles, but that doesn't really get you anywhere. In particular, the creator doesn't get anywhere with it. Something like this simply has to arise from the naive, from the elementary. Therefore, when I am asked how the individual form is conceived from the whole, I can only give the following answer. I can only say: look at a nut, for example. The nut has a shell. This nut shell is formed according to the same laws around the nut, around the nut kernel, according to which the nut itself, the nut kernel has come into being, and you cannot imagine the shell differently than it is, once the nut kernel is as it is.

Now one knows spiritual science. One presents spiritual science out of its inner impulse. One forms it into ideas, one brings them together in ideas. So you live in the whole inner being of this spiritual science. Forgive me, it is a trivial comparison, but it is a comparison that illustrates how you have to create out of naivety if you want to create something like the building in Dornach: you stand inside it as if in the nut kernel and have within you the laws by which you have to execute the shell, the building.

I often used to make another comparison. You see, in Austria we have a special kind of cake called 'Gugelhupf'. I don't know if that expression is also used here. And I said that one should imagine that anthroposophical spiritual science is the Gugelhupf and the Dornach building is the Gugelhupf pan in which it is baked. The cake and the pan must harmonize with each other. It is right when both harmonize, that is, when they are according to the same laws as nut and nut shell.

Because Anthroposophical spiritual science creates out of the whole, out of the fullness of humanity, it could not have the discrepancy within itself of taking an arbitrary architectural style for its construction and speaking into it. It is more than mere theory; it is life. Therefore, it had to provide not only the core but also the shell in the individual forms. It had to be built according to the same innermost laws by which one speaks, by which mysteries are presented, by which eurythmy is now presented. Everything that is presented in words, that is seen performed in eurythmy, that is seen performed in mystery plays, that is otherwise presented, must resound and be seen throughout the hall in such a way that the walls with their forms, that the paintings that are there, say yes to it as a matter of course; that the eyes, so to speak, absorb them like something in which they directly participate. Each column should speak in the same way as the mouth speaks, proclaiming anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Precisely because it is science, art and religion at the same time, anthroposophically oriented spiritual science had to establish its own architectural style, disregarding all conventional architectural styles. Of course, one can criticize this to no end; but everything that appears for the first time is imperfect at first, and I can perhaps assure you that I know all the mistakes best and that I am the one who says: if I were to rebuild the building a second time, it would be based on the same spirit, on the same laws, but it would be completely different in most details and perhaps even as a whole. But if anything is to be tackled, it must be tackled once, as well as one can at that particular moment. It is only by carrying out such a work that one really learns to know the actual laws of one's being. These are the laws of destiny of spiritual life and spiritual progress, and these have not been violated in the erection of the building at Dornach.

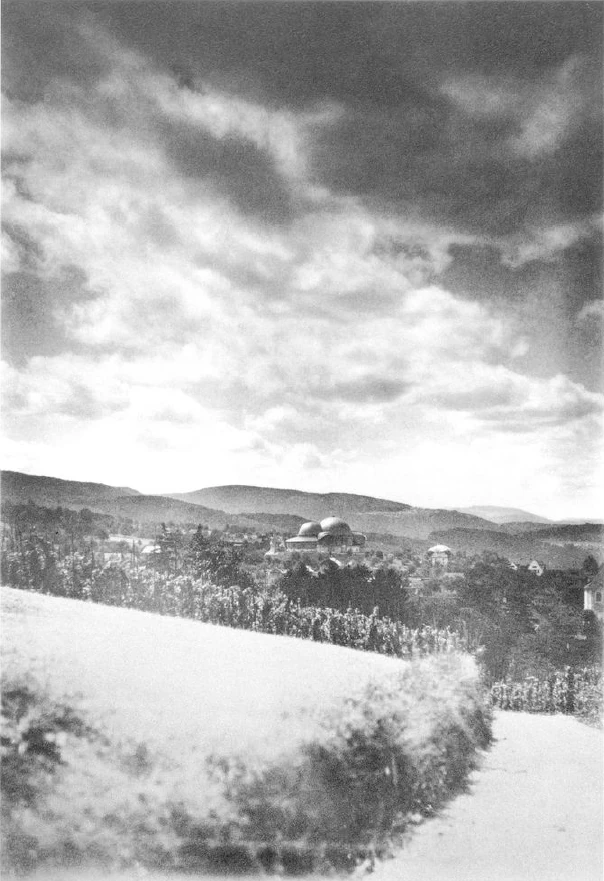

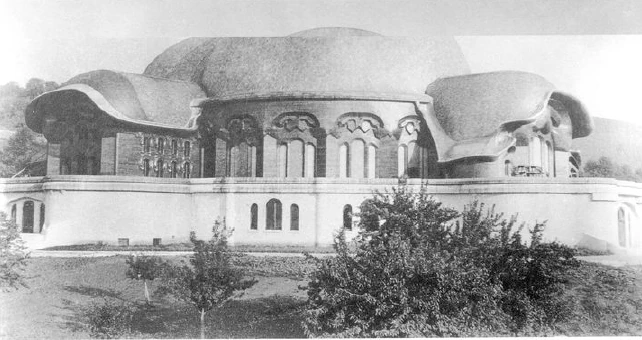

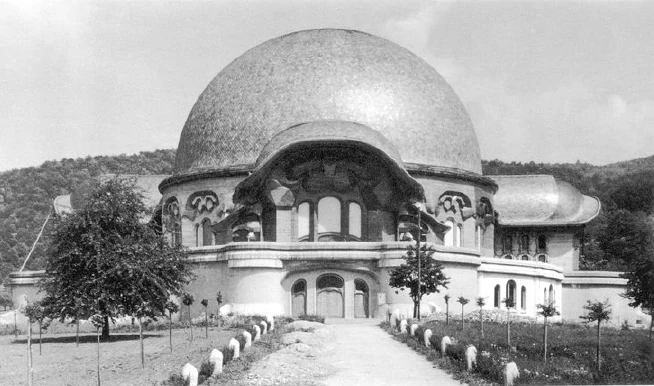

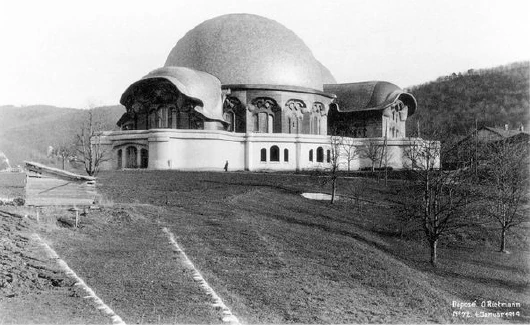

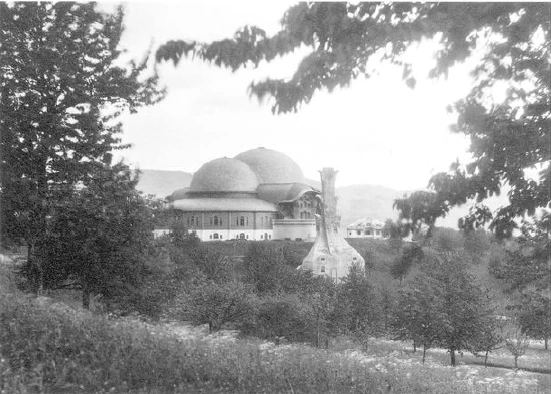

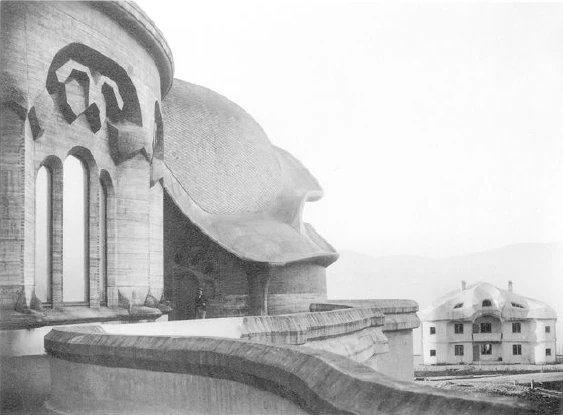

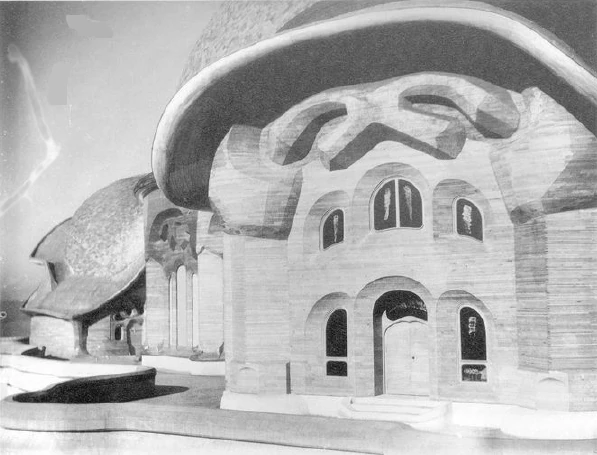

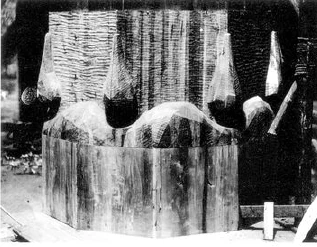

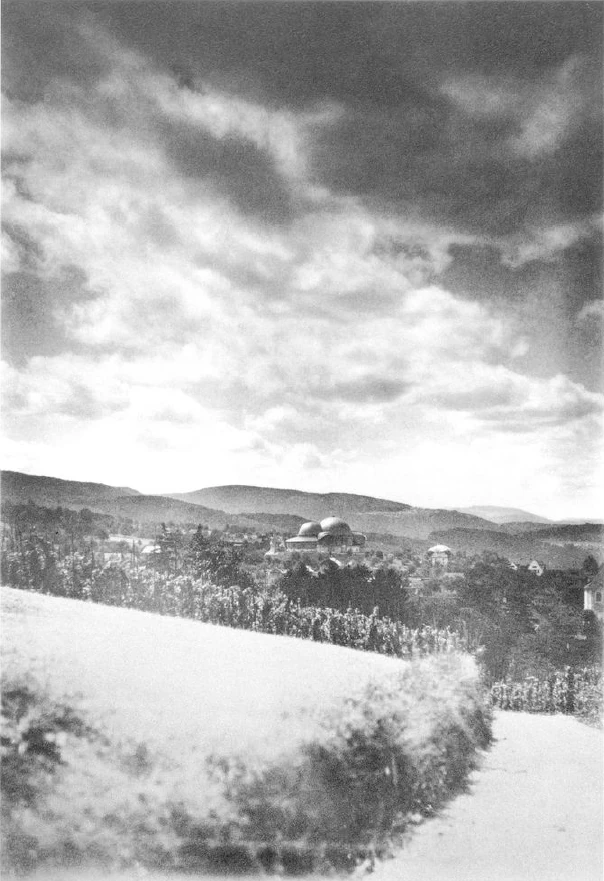

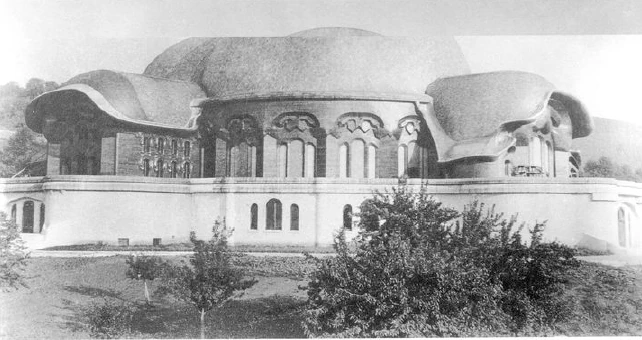

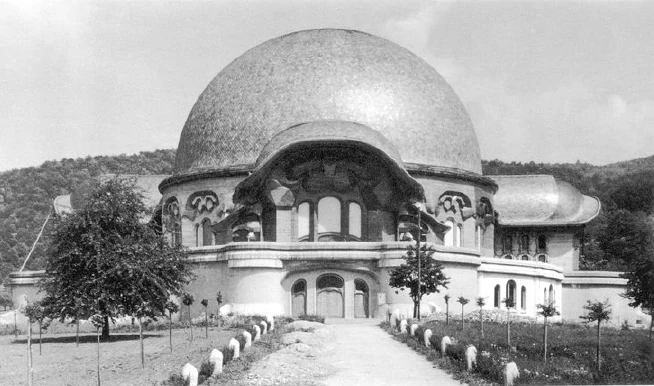

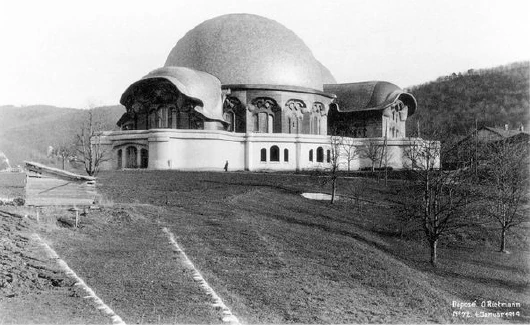

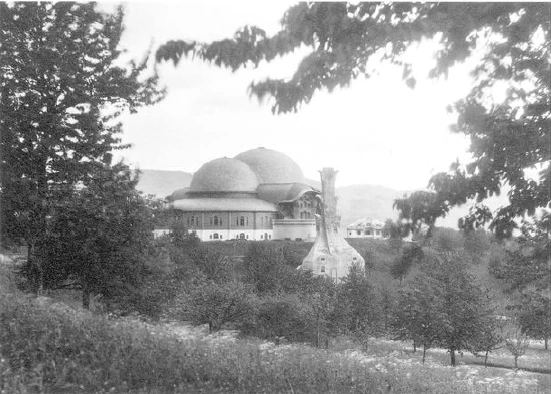

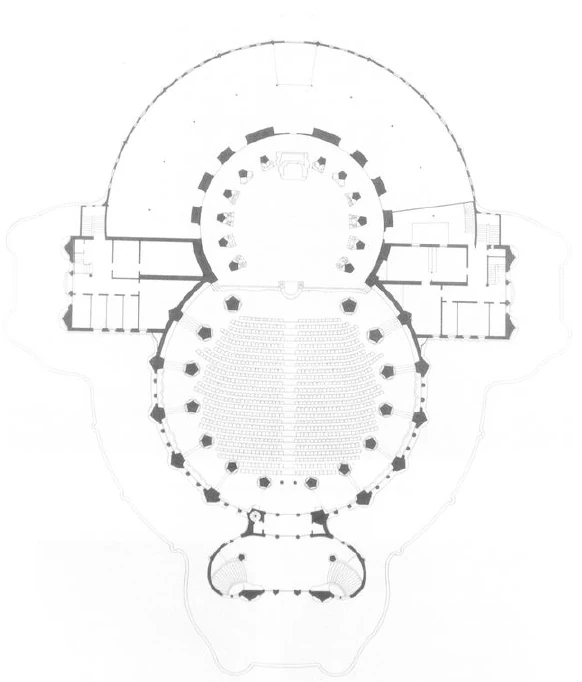

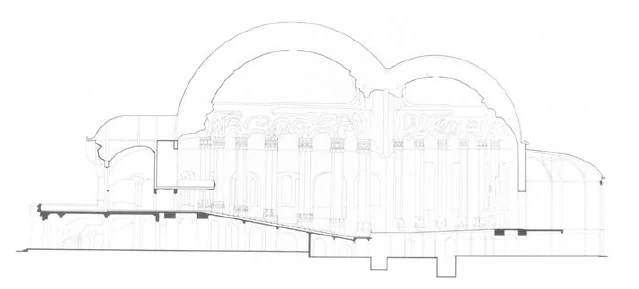

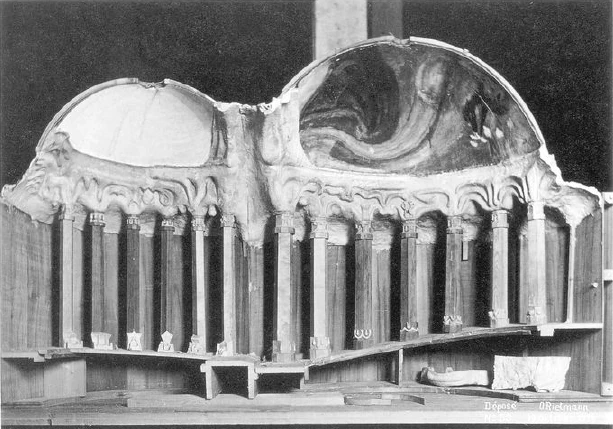

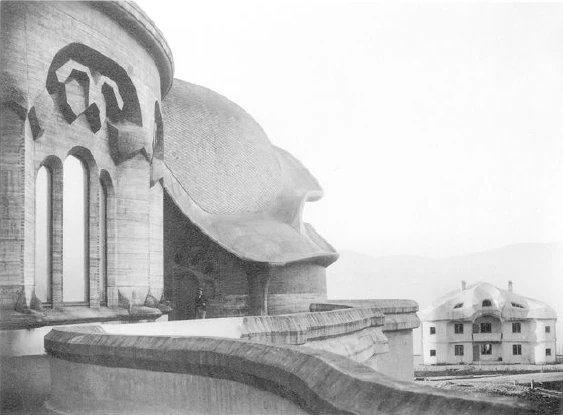

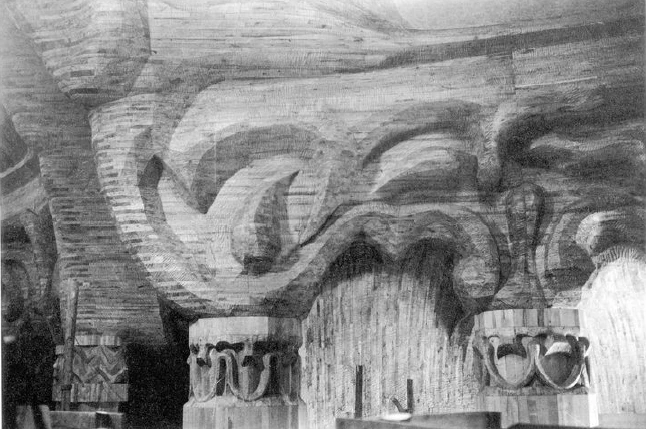

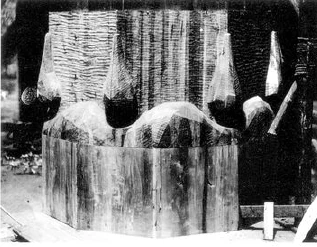

Now the building rises up on the Dornach hill (Fig. 1). Its basic forms had to be sensed first, emerging from the Dornach hill. That is why the lower part is a concrete structure (Fig. 4). I tried to create artistic forms out of this brittle material, and yet some have felt how these forms connect to the rock formations, how nature merges with the building forms with a certain matter-of-factness. Then, on the horizontal terrace, up to which the concrete structure extends, the wooden structure rises. This wooden structure consists of two interlocking cylinders, which are closed off by two incomplete hemispheres that are, as it were, interlocked in a circle, so that two hemispheres, two consecutive hemispheres, enclose the two cylindrical spaces as if they were placed one inside the other. A larger room, the auditorium, a smaller room, the one from which eurythmy is performed, mysteries are played and so on. Between the two rooms is the speaker's podium. This is initially the main building.

Of course, I must not fail to mention that in recent years numerous friends, particularly from this or that scientific field, have now found each other from almost all scientific fields, who have seen through and recognized how natural science, mathematics, history, medicine, jurisprudence, sociology, and the most diverse fields can be fertilized by anthroposophical spiritual science. So that a real Universitas must attach itself to Dornach, and for this the building, for which we have been able to provide for the time being, is nothing more than a large lecture hall, with the possibility of working in this lecture hall, which is intended for about a thousand people, in other ways than through the mere word.

That the building has this dualistic form, I would say, consisting of two cylinders crowned by hemispheres, can be sensed from the whole task that spiritual science, as we understand it in Dornach, must set itself. After all, this is based on what is called inner human development. One does not arrive at this anthroposophical spiritual science by merely using one's ordinary everyday power of judgment - although, of course, full reliance is placed on this - or by using the ordinary rules of research; but rather by

you must bring to the surface the powers slumbering in the soul, as described in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds”, and really ascend to that region where the supersensible powers and entities of existence reveal themselves to you. This revealing of the supersensible world to the sensory world, which expresses itself in the fact that the thousand listeners or spectators sit there and on the other side exactly that which gives knowledge of supersensible worlds is communicated, this whole thing, transformed into feeling, expresses itself in the double-dome building in Dornach. It is not meant to be symbolic in any way. That is why I can also say: Of course one could also express this thought differently, but that is how the artistic expression of this basic thought presented itself to me at the time when it was needed.

In a sense, by approaching it from the environment, in the external form of the wooden structure growing out of the concrete, which is a double dome, one sees in the configuration, in the design of the surfaces, what is actually meant by anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. The fact that they really tried not to calculate with abstract concepts, but with artistic perception, may become clear to you from the fact that - in the time when it was still possible before the war - Norwegian slate was obtained with all possible efforts to cover the two domes. Once, when I was on a lecture tour in 1913 between Christiania and Bergen, I saw the wonderful Voss slate. And this Voss slate now shines in the sunshine from the double domes, so that one actually has the feeling: this greenish-greyish shine of the sun, which reflects itself there, actually belongs in this whole landscape. It seemed to me that the care that had been taken to bring out the shine of the sun in the right way in such a landscape was something that showed that account had been taken to present something worthy in this place, which, as a place, as a locality, has something extraordinary about it.

I will now take the liberty of showing you a series of slides of what has been created as this Goetheanum in Dornach. They are intended to show in detail how what I have just explained, how the Dornach building idea has actually been realized. The Dornach building idea should present the same thing to the beholder in the outer spatial form in the picture, as it unfolds to the listener through the word, so that what one hears in Dornach is the same as what one sees in Dornach. But because it should really present a renewal out of spiritual life, a renewal of everything scientific, it also needed, in a sense, a new art.

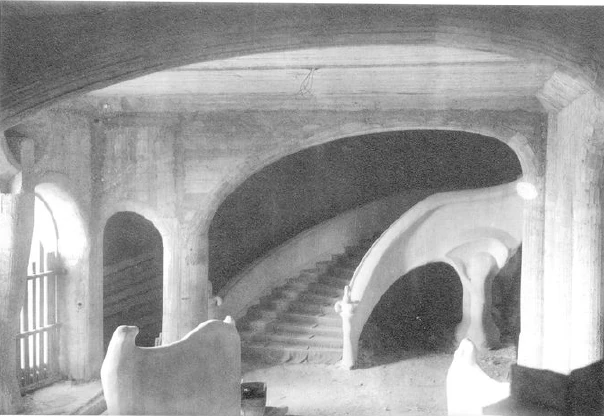

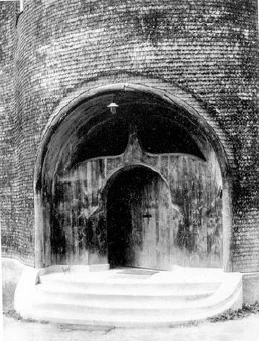

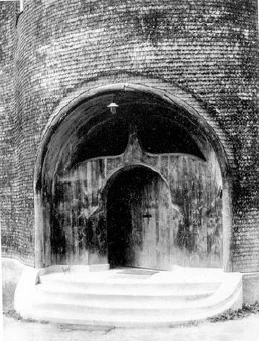

Now the first picture (Fig. 4): You see here the building, the dome is somewhat covered here, here the concrete substructure. When one approaches via a path that leads from the northwest towards the west gate, one has this view. This is therefore the concrete substructure with the entrance; here one goes in first. Further back in this concrete building are the storage rooms. After you have taken your things off, you go up the stairs that lead through this room, to the left and right, and first come to a vestibule – which you can also enter from the terrace through the main gate – and from there to the auditorium. Here you see, starting from this terrace and going up, the wooden structure covered with Nordic slate (Fig. 10). You can see from the shape above the main entrance in the west that an attempt has been made to incorporate something here that really does look like an organic form growing out of the whole of the building. It is not some random thing found in the organic world, copied from nature, but an attempt to explore organic creation itself. The aim is to devote oneself to organic creation in nature in order to have the possibility of forming such organic forms oneself and to shape the whole into an organic form without violating the dynamic laws. I would like to emphasize: without violating the dynamic or mechanical laws.

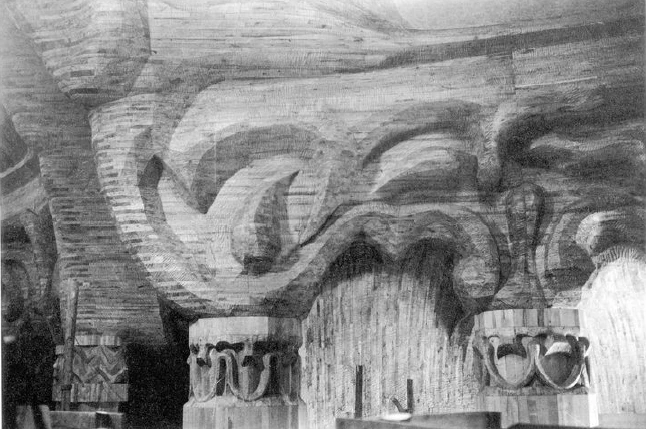

Anyone who studies interior architecture with us in Dornach will see everywhere that, despite the fact that columns, pillars and so on are organically designed, it is precisely in this organic design that what is properly supported and properly weighted is expressed, without it being expressed in the thickness of the columns or in the heaviness of any load. The correct distribution of load and support is achieved without the aid of organic forms, so that one has the feeling, as it were, that The building feels both the load and the support at the same time. It is this transition to the appearance of consciousness, as it is in the organic, that had to be striven for in this building, out of the anthroposophical-spiritual-scientific will. So without in any way violating the mechanical, geometric, symmetrical laws of architecture, the form should be transformed into the organic.

The next picture (Fig. 5): Here you see the concrete structure from a slightly further point and more from the west front; here the terrace, then the main entrance. The same motif appears here. The second dome, the smaller one, which is for the stage, is covered here; on the other hand, you can see, as it were, what is adjacent to it. Where the two domed structures connect, there are transverse structures on the left and right with dressing rooms for the actors in mystery plays or eurythmy performances, or offices and the like. These are therefore ancillary buildings here. We will see in a moment in the floor plan how these ancillary buildings fit into the overall building concept.

The next picture (Fig. 7): Here you see the building from the southwest side: again the West Gate, the great dome, another tiny bit of the small dome, to the south the southern porch; here the whole front between west and south.

The next picture (Fig. 3): Here you see the two domed rooms, the auditorium, from the other side, from the northeast, one of the transverse buildings from the front, here the small domed room and here the storage rooms that adjoin the small domed room to the east; furthermore, the terrace, and below the concrete building. This is the porch that leads to the west gate, which you have just seen.

The next picture (Fig. 2): This is the strange building that is particularly heavily contested. This is what you see when you look at the building from the northeast side: you then see this heating and lighting house. It is also the case that one was obliged to form something out of the brittle concrete material, and that one said to oneself, out of artistic laws, out of artistic feelings: There I am given everything that is necessary as a lighting machinery, as a heating machinery: that is the nut kernel to me, around which I have to form the nutshell, to form the necessary for the smoke outlet. It is, if I may express myself in such a trivial way, this principle of the formation of the nutshell is fully implemented. And anyone who complains about something like that should consider what would be there if this experiment had not been carried out, which may still have been imperfectly successful today. There would be a red chimney here! A utilitarian building should be created in such a way that one first acquires the necessary sense of material and then finds the framing from the determination.

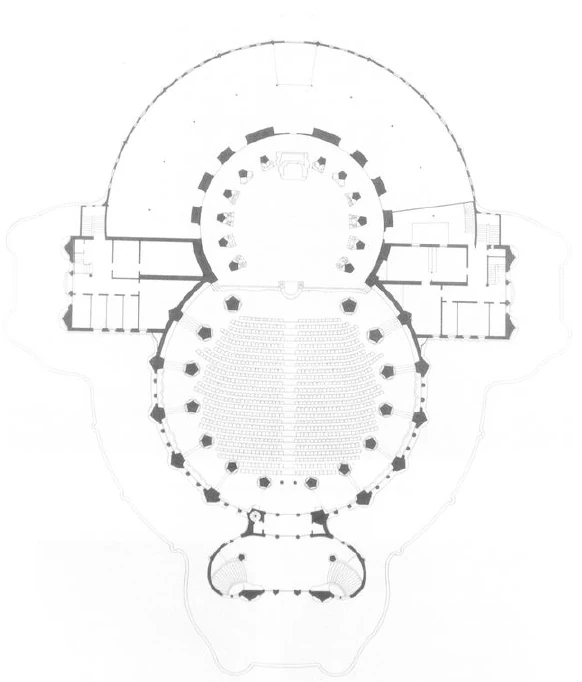

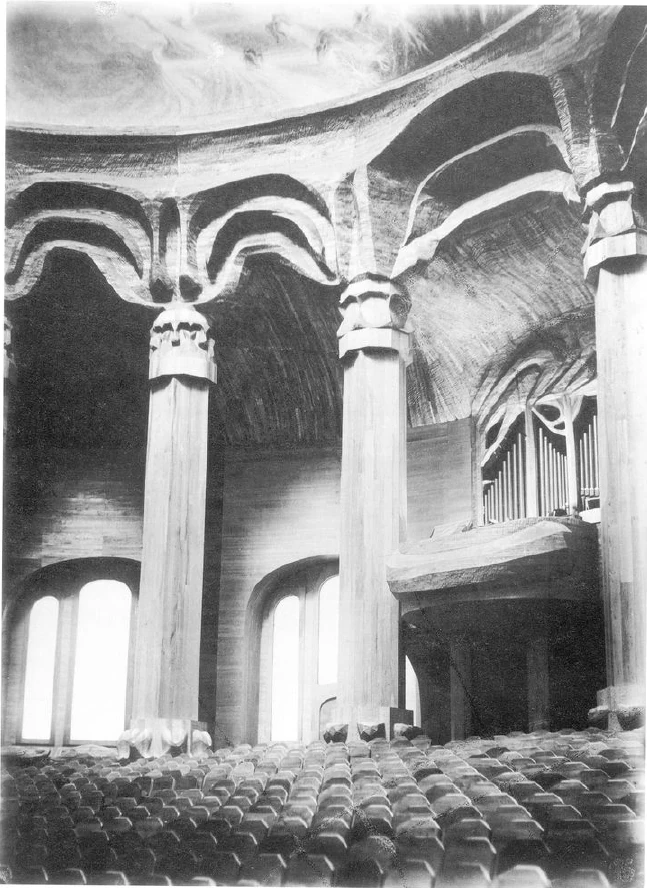

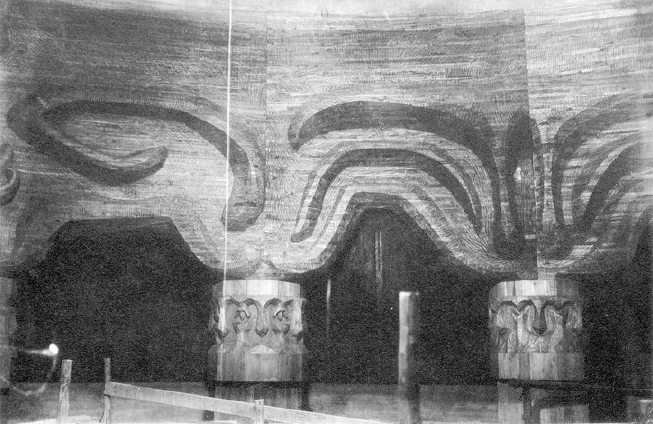

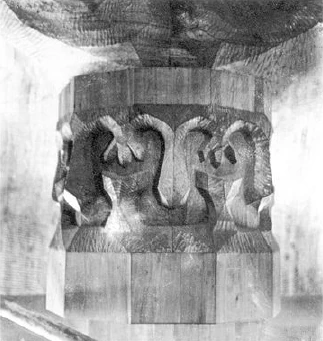

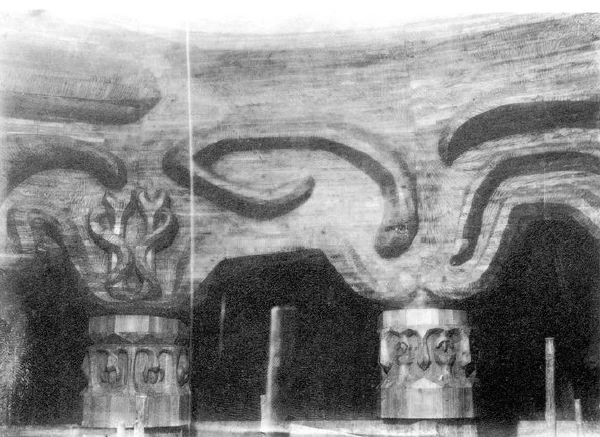

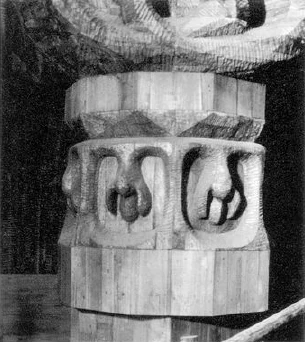

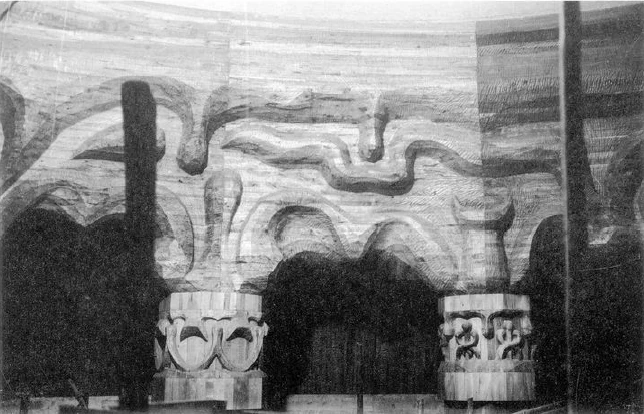

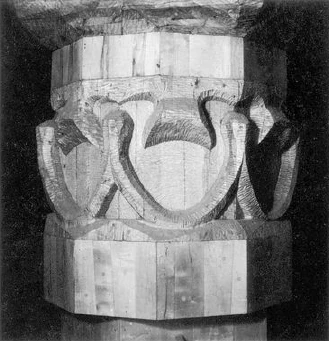

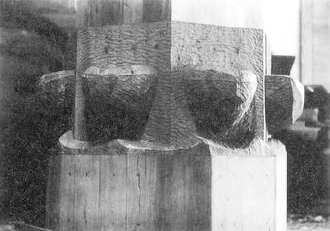

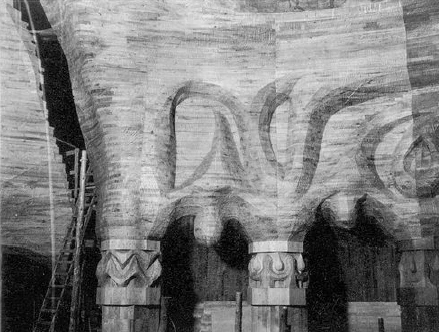

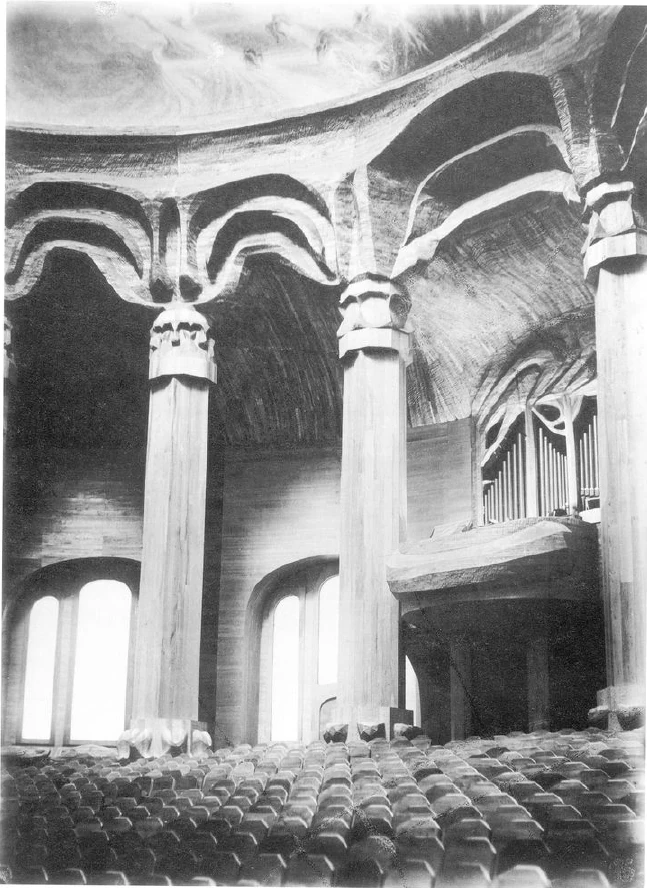

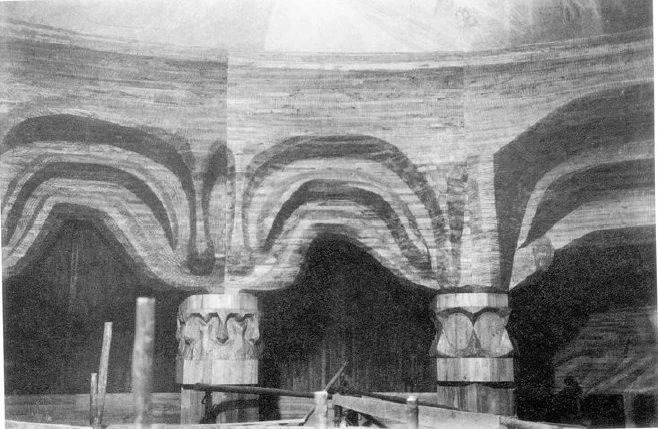

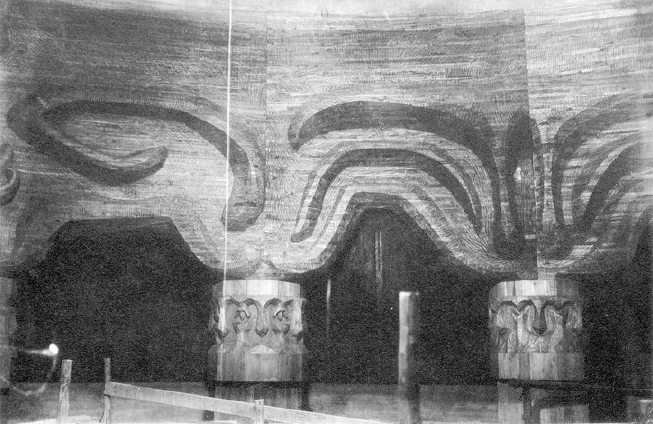

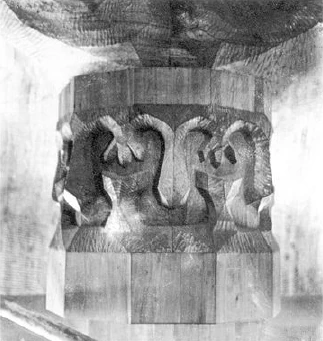

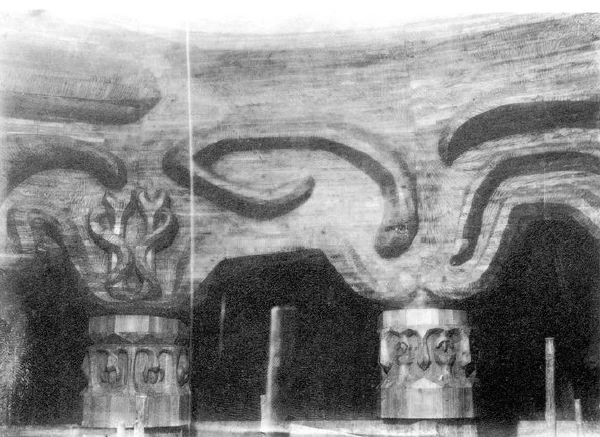

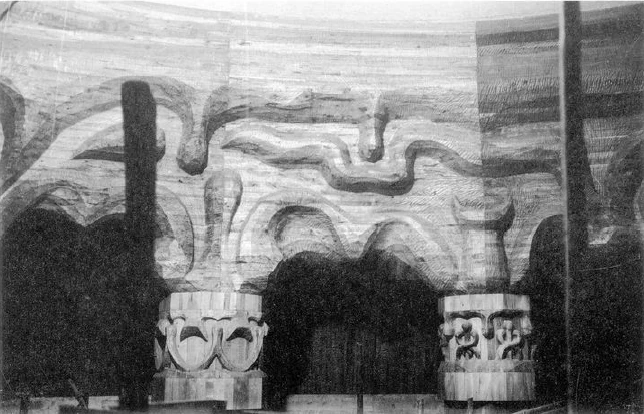

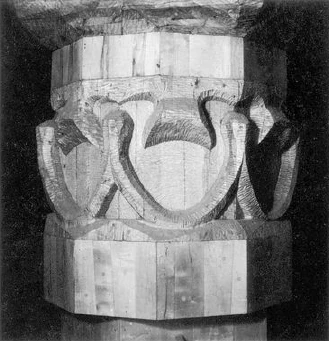

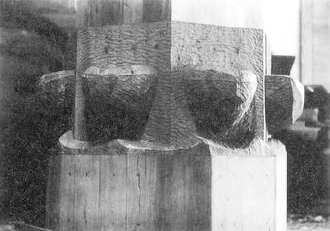

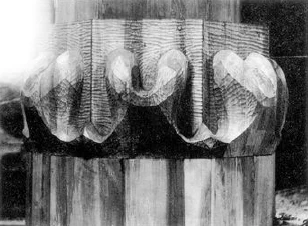

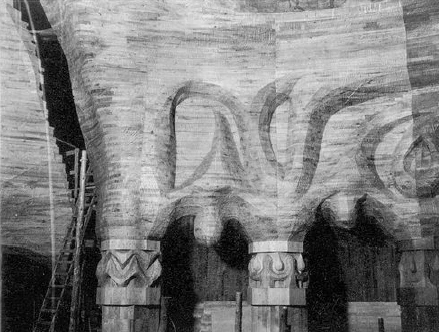

The next picture (Fig. 20): Here I take the liberty of showing the layout of the whole. The main entrance from the west: you enter the auditorium through a few vestibules. This auditorium holds chairs for nine hundred to a thousand listeners or spectators. Here you can see a gallery that is closed inwards by seven columns on each side. Only one thing is symmetrical here: namely, in relation to the west-east axis. This is the only axis of symmetry. The building's motifs are only designed symmetrically in relation to this axis of symmetry, the east-west axis; otherwise there is no repetition. Therefore, the columns are decorated with capital and base motifs that are not the same, but are in progressive development. I will show this in detail later. So if you have a first column on the left and right, a second column on the left and right, the capital and base are always the same as those of the right column when viewed from the left, but the following columns always have different capitals, different bases and different architrave motifs above them (Figs. 33-54).

This is absolutely the case, and it has emerged as a necessity from organic building. And this is based on an artistic interpretation of Goethe's principle of metamorphosis. Goethe has indeed developed this metamorphosis theory - which, in my firm conviction, will still play a major role in the science of the living - in an ingenious way. Anyone who still reads his simply written booklet “Attempt to Explain the Metamorphosis of the Plant” from 1790 has before them a grandiose scientific treatise that, according to today's prejudices, simply cannot be sufficiently appreciated. If one wants to express it simply, one must say: Goethe sees the plant as a complicated leaf. He now begins with the lowest leaf, which is closest to the ground, follows the leaves upwards to the heart leaves, which are shaped quite differently than the foliage leaves, then the petals, which are even colored quite differently, then the stamens and pistils, which are shaped quite differently. Goethe says: “Everything that appears in such seemingly different metamorphoses in the leaves of the plant is such that it can be traced back to an ideal similarity and only appears in different metamorphoses for the external sense impression. Basically, the plant leaf always repeats the same basic form; only in the external sensual perception is the ideal similarity differently formed, metamorphosed.

This metamorphosis is the basic principle in the formation of all life. This can now also be applied to artistic forms and creations, and then one can do the following: First you shape the simplest capital or the simplest pedestal for the first column that you have here, and then you surrender, as it were, to the creative forces of nature, which you first tried to listen to – not with abstract thought, but with inner sensation, which, with a will impulse, has listened to a part of nature's creation. And then one tries to create a somewhat more complicated motif of the second column from the simple motif of the first column, just as the leaf a little higher on the plant is more complicated than the one before, but represents a metamorphosis. So that all seven capitals are actually derived from each other, growing out of each other metamorphically, like the forms of the leaves that develop one from the other in the plant's growth, forming metamorphically. These capitals are thus a true recreation of nature's organic creation, not simply repeating the same motif, but rather the capitals are in a state of continuous growth from the first to the seventh.Now, of course, people come and see seven columns – deep mysticism! Yes, there are definitely members of the Anthroposophical Society who, in all sorts of dark, mysterious allusions, talk about the deep mysticism of these seven columns and so on. But there is nothing in it but artistic feeling. When you arrive at the seventh column, this motif of the seventh column is exactly the same as that of the first column – if you really create as nature has created – as the seventh is to the first. And just as the first motif is repeated in the octave, the seventh, you would have to repeat the first motif if you were to move on to the eighth.

Here you can see the boundary between the large and small domes; there is the lectern, which can be retracted because it has to be removed when the theater is in use. Here again there are twelve columns in the perimeter, here the boundary of the small domed room, here the two transverse buildings for dressing rooms and so on.

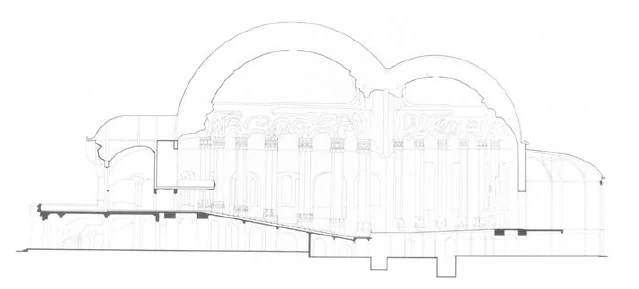

The next picture (Fig. 21): Here I have made a section through the middle. One enters from the west through the vestibules. Here is the stage area, and rising up from here is the auditorium, the rows of seats, again the seven columns, and here the great dome is connected to the small one by a particularly complicated mechanical structure. Here are the storerooms, the concrete substructure, the dressing rooms for taking off clothes. Here you go in, and then there are the stairs; here you come up and there is the main gate through which you enter.

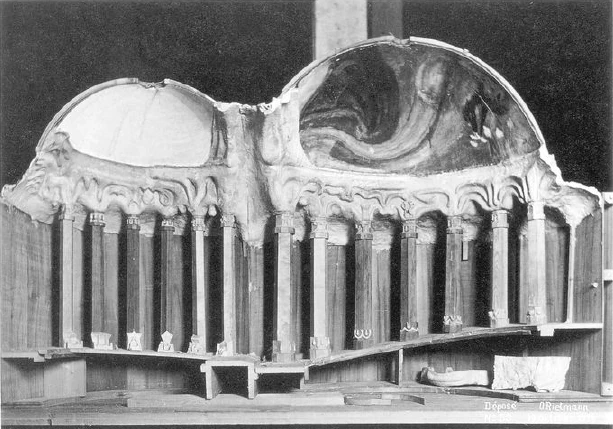

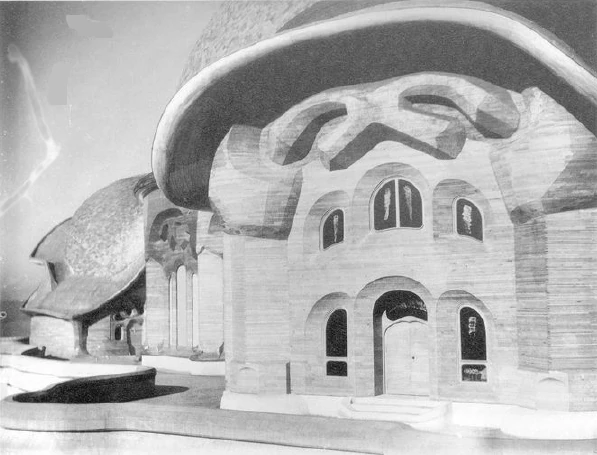

The next picture (Fig. 22): Here I have taken the liberty of presenting my original model in cross-section. The whole building was originally modeled by me in 1913. Here you see the auditorium with its seven columns, the vestibules, here only hinted at the interior of the great dome, which was then painted; here in the small dome room, the capitals everywhere – I will show them in detail in a moment – here the architrave motifs above them; here the plinth motifs, always emerging metamorphically from one another. So, as I said, it is 'only' a line of symmetry, the central axis of the building. Otherwise, no repetitions can be found, except for what is located on the left and right.

The next picture (Fig. 10): seen from the terrace, the view of the West Gate, the main entrance gate, with two wings, which are necessary [gap in shorthand].

The next picture (Fig. 12): there is such a wing structure, the northern one [seen from the northeast]. Dr. Großheintz's house is also located here, an entire concrete building with about 15 rooms, a family house where I tried to create a residential house out of the concrete material by integrating it into this concrete material. It is near the Goetheanum and was built for the person who donated the land. You can see here how I tried to metamorphose the motif. Everything about this building emerges from the other, like a plant leaf, so to speak, in its form from the other form: it is entirely in the artistic sense the work of metamorphosis.

Next image (Fig. 14): This is one of the side wings, the south wing. Here you can see how the motif above the west entrance appears in a completely different form. It is the same idea, but completely different in form. It is just as, say, the dyed flower petal is the same idea as the lowest green leaf of the plant, and yet in external metamorphosis it is something completely different. In this way, one can indeed sense this organic building-thought by living and finding one's way into the metamorphic by giving oneself up to it, but understanding it in a feeling-based way, not in an abstract, intellectual way. This should not actually be explained, but everything should be given by the sight itself.

Once the building is finished, those who are familiar with the anthroposophical attitude and feeling will not perceive the building as symbolic at all, but as something that flows from this overall attitude. Of course one would say that it should flow out of the “generally human”; but this generally human is only a foggy and fanciful construct, a fantasy. The human is always the concrete. Someone who has never heard of Christianity naturally does not understand the Sistine Madonna either. And someone who has no sense of Christianity would never understand the Last Supper in Milan in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. It is certainly possible to use language to imagine what was given, but apart from that, there is nothing symbolic about the entire structure; all the forms are metamorphosed variations of one another.

Next picture (Fig. 11): Here you see such a lateral transverse structure, viewed from the front, that is, here from the south side. Up here in a substantially modified metamorphosis is the motif that is also above the west entrance. All these motifs are in various metamorphoses, so that the whole architectural idea is carried out organically. Likewise, if you were to study the columns, you would find a basic form, and this is always metamorphosed, just as, in the end, the skull bones of humans are a metamorphosed transformation of the bones of the spinal cord, as everything in the organism is a metamorphosed transformation right down to the last detail.

The upper part (Fig. 14) of the southern transverse structure seen on its own; this motif, which was just a little smaller there, is now a little larger.

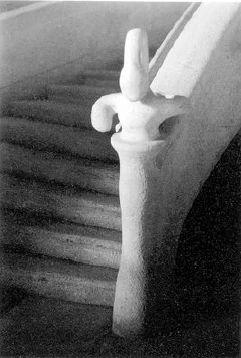

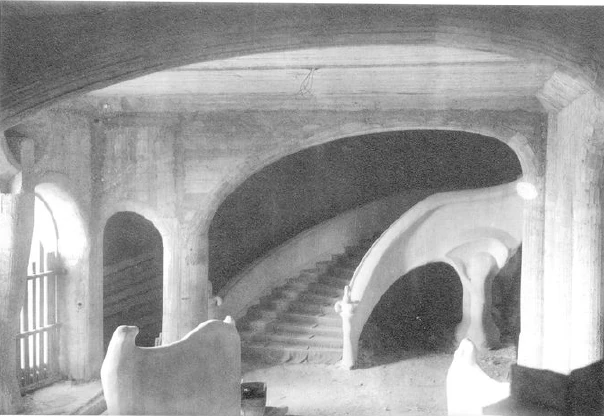

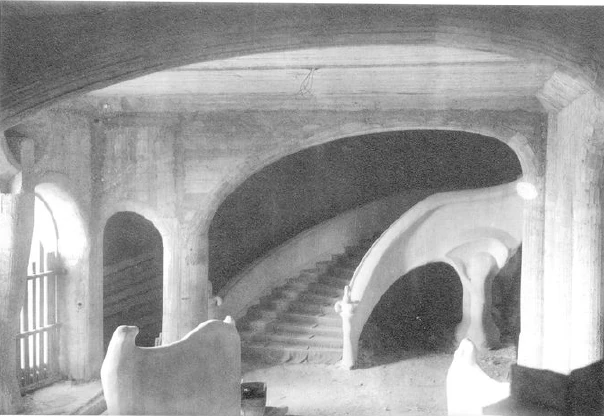

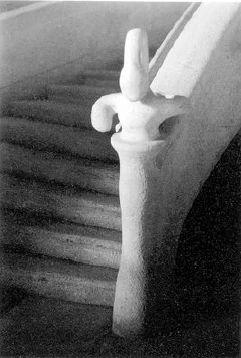

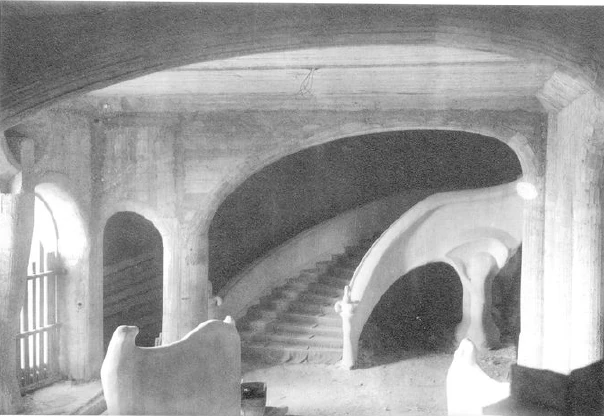

Next picture (Fig. 23): Here you can see part of the staircase. You would enter through the main entrance below, into the concrete building, and go up these stairs. Here you can see the banister and here a pillar. On this pillar you can see how the attempt is made to shape the supporting pillar in an organic form, how the attempt is made to give the pillar the form that it must have after the opposite exit, because there is little to carry; the form that it must have where it is braced, where the entire weight of the staircase lies. Of course, something like this can only be formed geometrically. But here, for once, an attempt should be made to shape the whole thing as if it were alive, so that, as it were, the glow of consciousness of bearing and burdening lies within; with every curve, everything is precisely and intuitively measured for the place in the building where it is located.

Especially if you look at this motif here (Fig. 24): there are three half-circular channels on top of each other. Believe it or not, but it is true: when someone goes up there and enters the auditorium, they must have a certain feeling. I said to myself, the one who goes up there must have the feeling: in there, I will be sheltered with my soul, there is peace of mind to absorb the highest truths that man can aspire to next. That is why, based on my intuitive perception, I designed these three semicircular channels in the three perpendicular spatial directions. If you now go up these stairs, you can experience this feeling of calm. It is not modeled on it – it is not that at all – but only later did I remember that the three semicircular channels in the ear also stand in these three directions perpendicular to each other. If they are violated, a person will faint: they are therefore connected with the laws of equilibrium. It was not created out of a naturalistic desire for imitation, but out of the same desire, which is modeled on the way the channels are arranged in the ear.

You enter from the west side, go up the stairs, here are the three perpendicular semicircular canals, and here again these pillars. Of course, it often happens in life – I have experienced it many times – that when people in a city have seen an actor or actress in certain roles, and later another actor or actress has come along who could be good, better, more interesting or different, they judge them based on the earlier ones. If they did everything exactly like the earlier ones, they were good; if they did it differently, they were bad, no matter how good they might be in themselves. And so, of course, people judge such a thing according to what they are accustomed to, and do not know that when something like this is erected, every effort is made to make it look as if it were supported in different ways on different sides, and that this is derived from the overall organic structure of the building. Some found it thin and called it rachitic, others thought it resembled an elephant foot, but could not call it an elephant foot either, and so someone came up with the name “rachitic elephant foot” based on their own intuitive feeling. This is what happens so often today when some attempt is made to bring something new out of the elementary.

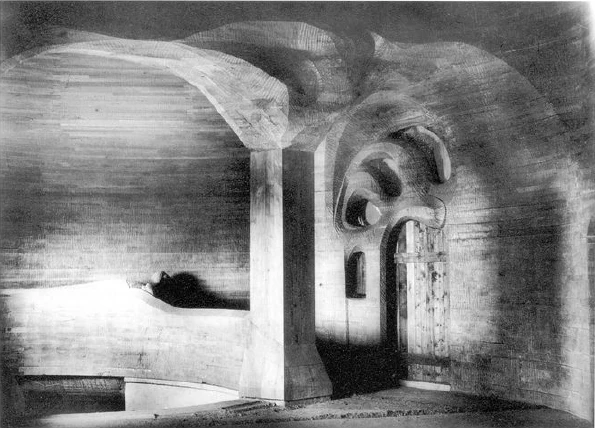

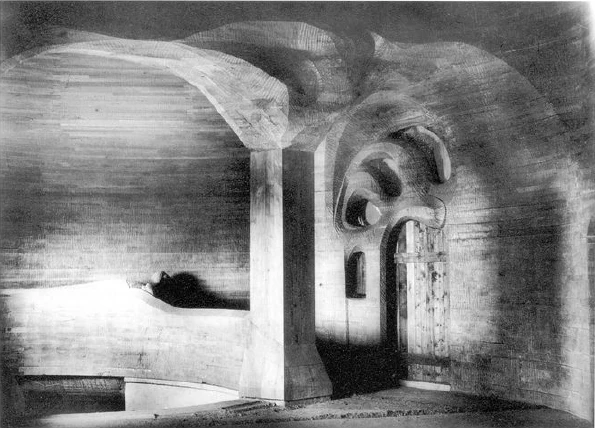

Next image (Fig. 27): If you go up the stairs, you will come to the vestibule before entering the large domed room. Here you can already see the beginning of the timber construction. At this height, there would be a concrete terrace, with the concrete structure below. You can see from this column how the capital, with all its curves, is precisely adapted to the location, not just schematically in space, but dynamically. The curves at the exit have to express a different form of support than those on the opposite side of the building, where the columns have to brace against them. That is why all these wooden forms, column capitals, architraves and so on had to be made by our friends from the Anthroposophical Society over many years of work. All this is handcrafted, including, for example, the ceiling, which does not have just any schematic form, but is individually designed on all sides in its curves and surfaces, hollowed out differently in one spatial direction than in the other spatial direction. And all this according to the law, just as the ear is hollowed out differently at the front than at the back, and so on.

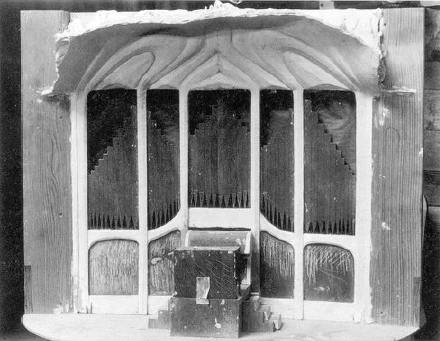

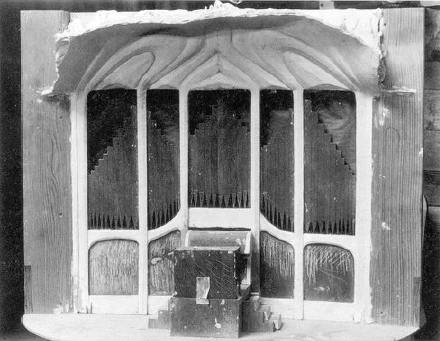

Next picture (Fig. 30): Now we have entered and are standing in the room that is the auditorium. If we turn around and look backwards, we see the organ room here, which you can see in more detail in other pictures. But here you only have the model, not as it can be seen now in the building, where a lot has been added. I have tried to integrate this organ in such a way that one does not have the feeling that something has been built into the rest of the space, but rather that at this point what is presented here as the organ case and the organ itself has literally grown out of the whole. That is why the architecture and sculpture are adapted to the lines created by the rest, i.e. the organ pipes and so on.

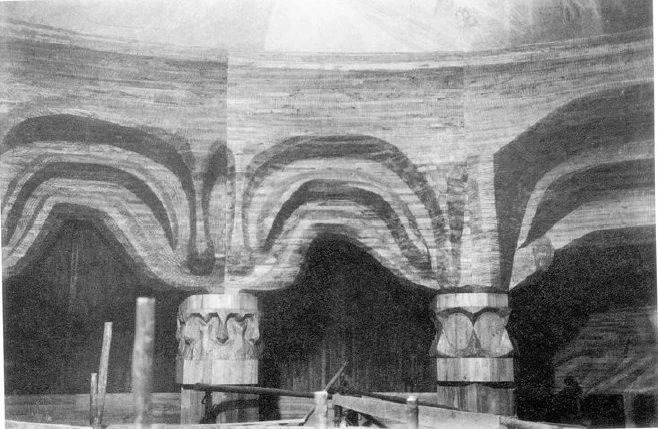

Next image (Fig. 28): You are now, so to speak, in the auditorium, looking from the auditorium at the columns. Here is the organ motif, here are the first two columns with their capitals. We then come to the altered, metamorphosed capitals of the second, third, fourth columns and so on – I will show this in detail in a moment – above them always the architrave motif and below the base motif. Next image (Fig. 29): The pictures were taken at different times. The construction has been going on since 1913, when the foundation stone was laid, and the pictures show it in various stages. Here again, if you turn around in the auditorium and look to the west, the upper part, the organ motif; the first and second columns with capitals on the left and right, the capitals and the architraves above them are quite simply designed. In the following, I will show one column and the one that follows, and then each column with the column capital on its own, so that you can see how the following column capital always emerges metamorphosically from the preceding one. This particularly emphasizes the fact that, basically, the individual column cannot be judged on its own, but only the entire sequence of columns in their successive form can be judged.

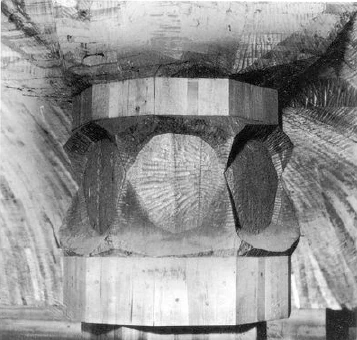

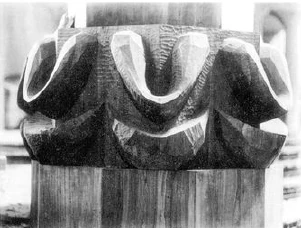

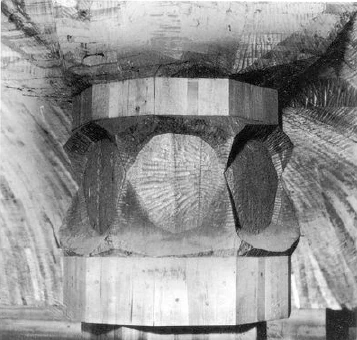

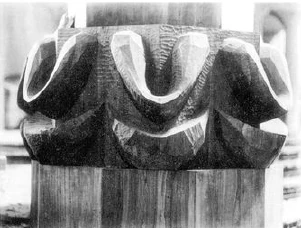

Next image (Fig. 34): Here you see the first column by itself, simply from bottom to top in the forms, simply from top to bottom. You see a very simple motif.

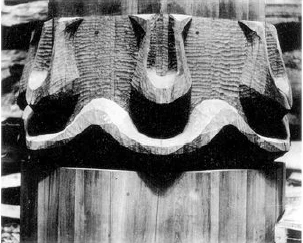

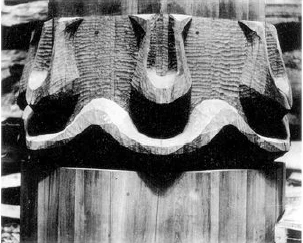

Next image (Fig. 35): Here you see the first motif, the first capital with the architrave above it; here the second, emerging organically from the first. The motif, which goes from top to bottom, grows; in growing, it metamorphoses, and so does the motif from bottom to top. To a certain extent, one has to feel one's way into the forces that are at work when an upper plant leaf is created in its form, metamorphosed compared to the lower one; in the same way, this first simple plant motif develops into a more complicated one. What matters is that you take the whole sequence of motifs, because each one always belongs with the other; in fact, all seven belong together and form a whole.

Next image (Fig. 36): Here you see the second column by itself. The next motif always emerges metamorphically from the previous one. I will now show the second and third columns.

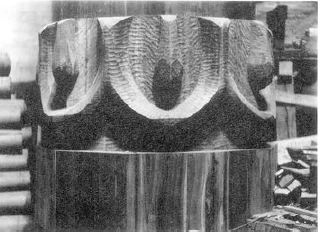

Next picture (Fig. 37): the second and third columns, again the third capital motif with the architrave motif above it is more complicated, so that you really get this complicated form in your feeling if you do not want to explain it symbolically or approach it with some intellectual things, but with feeling. Then you will see the emergence of one from the other.

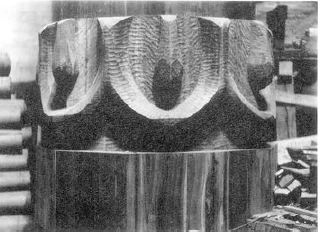

Next image (Fig. 38): The third column by itself.

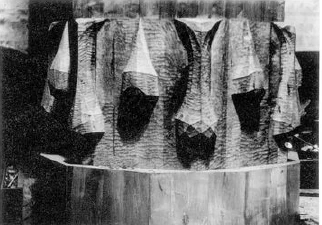

Next image (Fig. 39): The third and fourth columns, that is, the capitals of these with the architrave motif. Here one could believe that the search was for this architrave motif to form a kind of caduceus. But it was not sought, it is simply sensed, as these meeting forms, when they continue to grow, continue to complicate, as they become there, and then the sensation of this motif, which resembles the caduceus, arises by itself. Likewise, as if this continues to grow: from bottom to top, things simplify, from top to bottom they complicate; then this form arises, which I will now show again in isolation.

Next image (Fig. 40): The fourth column.

Next image (Fig. 41): The fourth and fifth column. As can be seen from this, if you imagine it growing downwards, this form emerges, and it becomes simpler from the bottom up, and I would say that it grows in a more complex form upwards. That is the strange thing! When you think of development, you believe, from a certain false idea of development that has gradually formed, that development proceeds in such a way that you first have a simple thing, then a more complicated one, and then an increasingly complicated one, and that the most perfect thing is the most complicated. If you now put yourself in the right place in the developmental impulses with artistic perception, you see that this is not the case at all; that you must indeed advance from the simple to the more complicated; but then you arrive at the most complicated in the middle of the development, and then it becomes simpler as it approaches the more perfect.

That was, my dear attendees, while I was working on the models for these things, an extraordinary surprise for me. I had to go from the simple to the complicated - you see, we are here at the fourth and fifth pillars, so roughly in the middle of the seven pillar forms - and I had to have the most complicated thing in the middle and then go back to the simpler. And if I go back, as nature itself creates, I also find the human eye, but the human eye, although it is the most perfect, is not the most complicated. In the eye of certain lower animal forms, for example, we have the fan, the xiphoid process. The eye of certain lower animal forms is more complicated in some respects than the perfect human eye. In nature, too, it does not happen that one goes from the simpler to the more complicated and then further to the most complicated, but by observing things further, one comes back to the simpler. The more perfect is simpler again. And that turns out to be an artistic necessity in such a creative process.

Next image (Fig. 42): The fifth column in itself.

Next image (Fig. 43): Now the fifth and sixth columns. You can see that here the capital of the fifth column is still relatively complicated; if it continues to grow, it becomes simpler again: so that this sixth column, although more perfect in its design, is nobler, is simpler again. The same applies to the architrave motif.

Next image (Fig. 44): This sixth column stands alone.

Next image (Fig. 45): Sixth and seventh column, considerably simplified again. Next image (Fig. 46): The seventh column on its own, again simplified.

Next image (Fig. 47): This is the seventh column, the architrave motif; here is the gap between the large and small domed rooms; here is the curtain. Then the first column of the small domed room, and here we enter the small domed room.

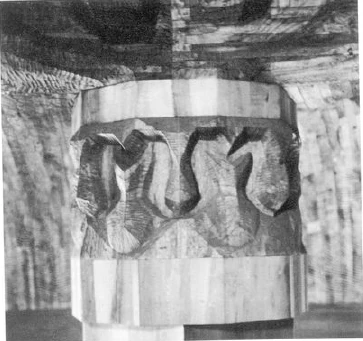

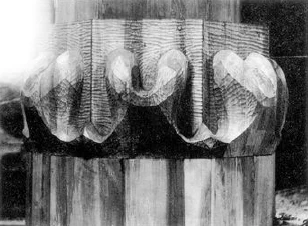

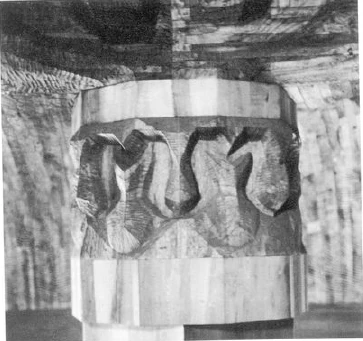

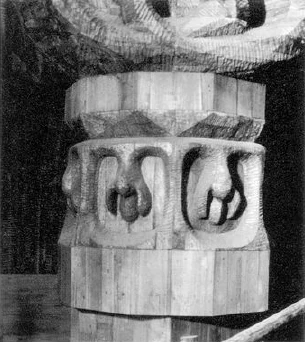

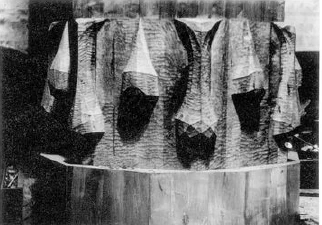

Now that we have gone through the orders of the columns in the large domed room, I will show you the figures on the pedestals, which have also grown out of each other in a metamorphosing organic way. I will show them in quick succession.

Next image (Fig. 48): Here I show the figures on the pedestals in succession. First pedestal.

Next image (Fig. 49): Each one always emerges metamorphically from the other: Second plinth.

Next image (Fig. 50): If you now imagine the changes, this is what happens: Third base.

Next image (Fig. 51): Fourth pedestal, again more complicated. And now the simplifications begin with the pedestal figures, in order to arrive at perfection.

Next image (Fig. 52): Fifth pedestal. Next image (Fig. 53): Sixth pedestal. Next image (Fig. 54): This seventh pedestal figure is relatively simple again.

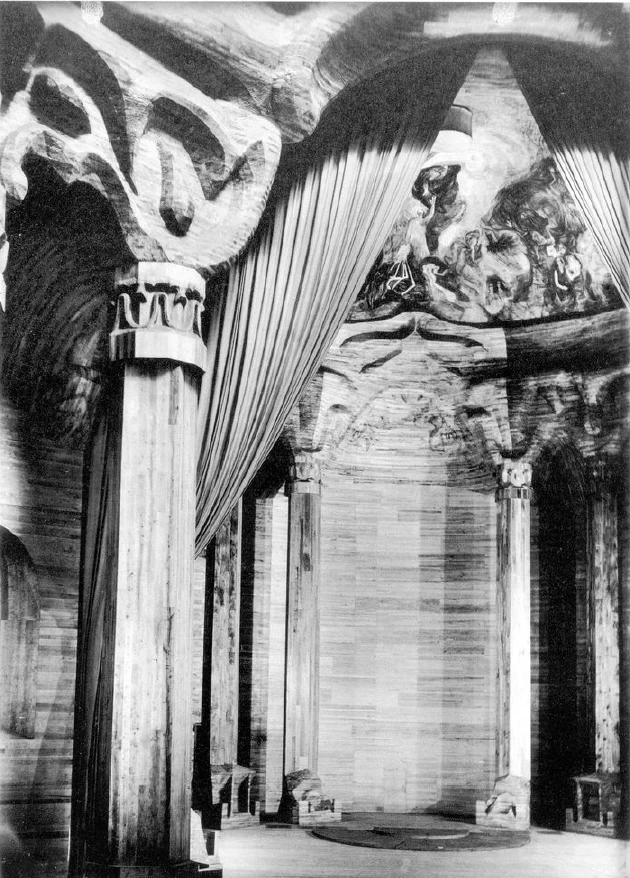

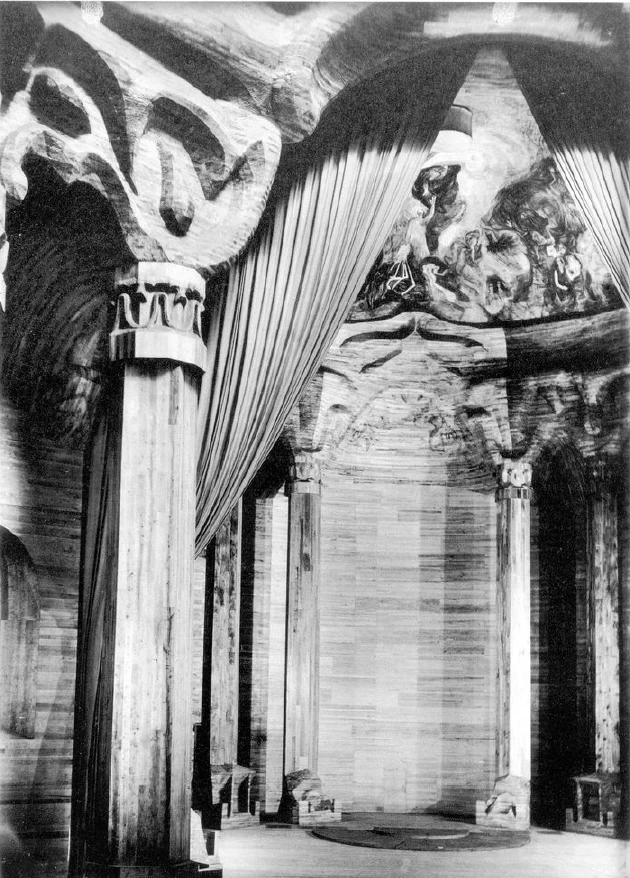

Next image (Fig. 55): Now, here you can see into the small dome room from the auditorium. You can still see the last column of the auditorium, then the columns and architraves of the small dome room. That is the end of the large dome room, here the center of the small dome room. Here, a kind of architrave is formed between the two central columns of the small dome, but [above it] is not some kind of symbolic figure. If you want to see a pentagram in it, you can see it in every five-petalled flower. We have [below] synthetically summarized all the lines and curves that are distributed on the individual columns. Above, the small dome is then painted. I will have more to say about this coloring.

The next picture (Fig. 56): individual columns of the small domed room. Here the gap [for the curtain]. It is seen here on the left when entering from west to east. Here is the architrave of the small domed room. Here, as you can see, the capitals of the large domed room are not repeated, they correspond to the overall architectural concept. Since the small dome room is smaller and every organ that is smaller in the organic context also has different forms, this is also clearly evident here in the formation of the whole.

The next picture (Fig. 64): Here again is the view into the small domed room, the last two columns of the large domed room; the same motif that you have just seen in a different aspect, and here the small dome. Of course, nothing of the paintings can be seen here, only the situation could be hinted at. The bases of the small columns have been converted into seats.

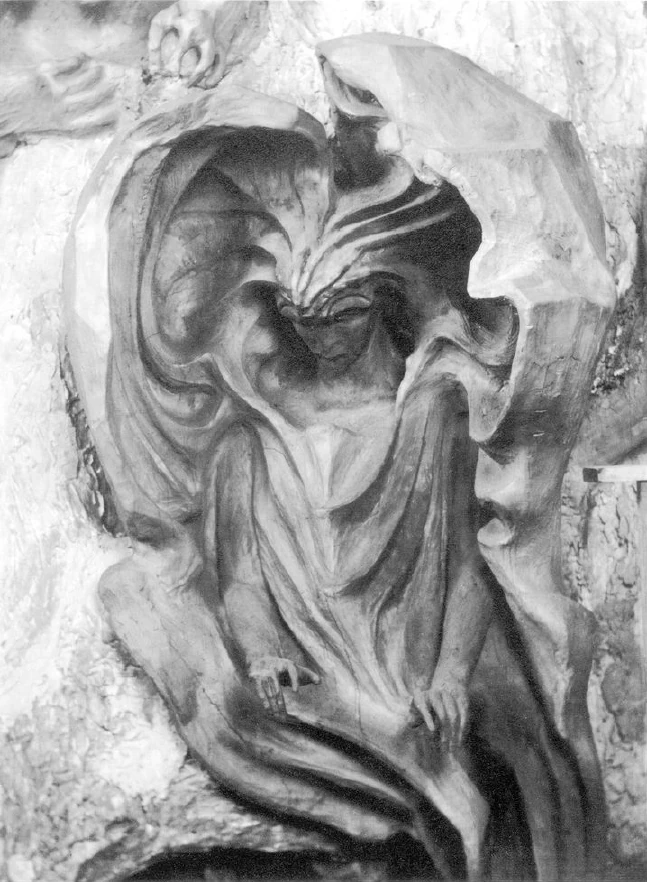

The next picture (Fig. 67): Here the orders of columns continue to the left and right; this is in the middle in the east, directly under the small domed room, where all the lines and curves found elsewhere are synthetically summarized in the most diverse forms. This is a kind of architrave, a central architrave; below it is the group I will talk about, a nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group, the central figure of which represents a kind of human being. Above it is the small domed room.

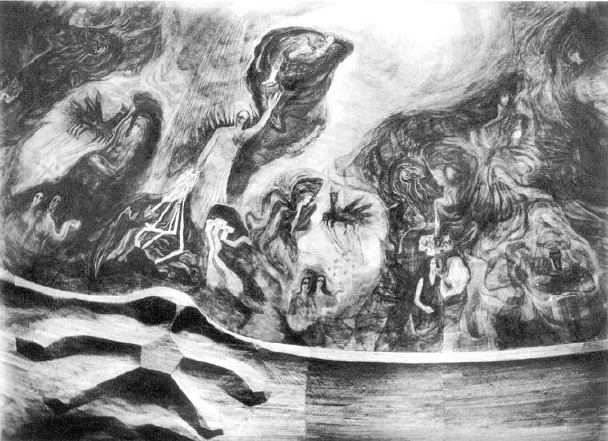

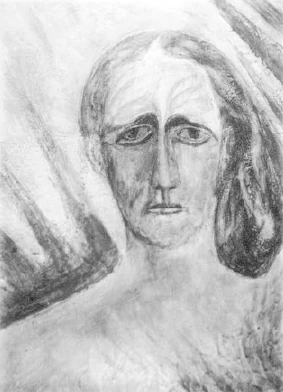

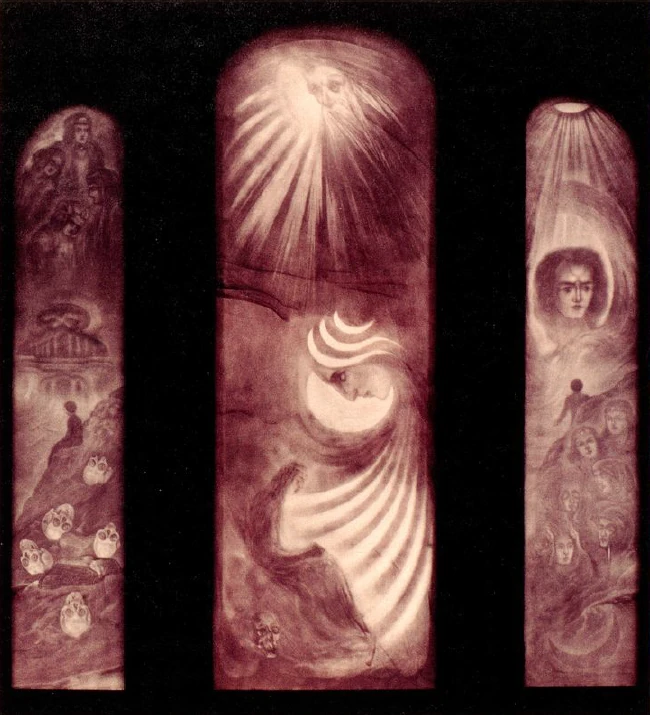

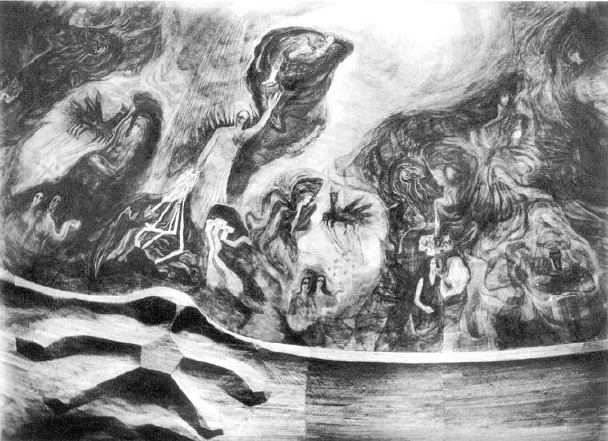

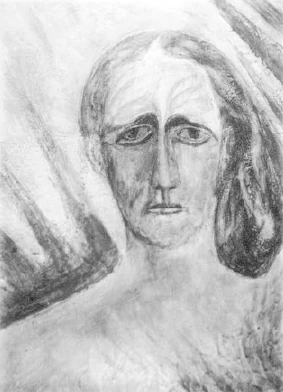

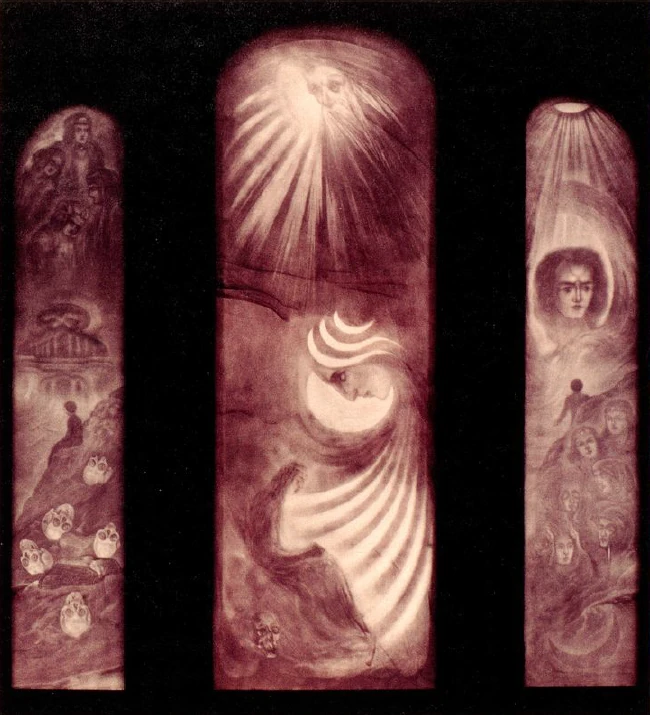

The next picture (Fig. 69): We now come to the painting of the small domed room. Now, by speaking to you about the painting of the small domed room, I can only show you the pictures of this small domed room. In the painting of the large domed room, I have not yet fully succeeded in doing this, but in the painting of the small domed room, I have tried to realize to a certain extent what I had a character in my mystery dramas express about the new painting: that the forms of color should be the work, that is, that one should really pull oneself together to fully perceive the world of color as such.

Dear attendees! If you look at the world of colors, it is indeed a kind of totality, a world of its own. And if you feel very vividly into the colorful, then I would say red and blue and yellow speak to each other. You get a completely lively feeling within the world of colors and you get to know, so to speak, a world of colors as an essential one at the same time. Then drawing stops, because in the end you perceive drawing as something insincere. What then is the horizon line? If I draw it with a pencil, I am actually drawing an untruth. Below is the green surface of the sea, above is the blue surface of the vault of heaven, and when I put these down as color, the form arises, the line arises as the boundary of the color.

And so you can create everything out of the colored that you essentially want to bring onto the wall as painting – be it the wall of the spheres as here or the other wall. Do not be deceived because there are motifs, because there are all kinds of figures on it, even figures of cultural history. When I painted this small dome, it was not important to me to draw these or those motifs, to put them on the wall; what was important to me was that, for example, there is an orange spot here in different shades of orange: the figure of the child emerged from these color nuances. And here it was important to me that the blue was adjacent: the figure emerged, which you will see in a moment. It is definitely the figure, the essence, drawn entirely from the color. So here we have a flying child in orange tones, here would be the gap between the large and small domed rooms, and the child is, so to speak, the first thing painted on the surface of the small dome. But by seeing these motifs, you will best understand the matter if you say to yourself: I can't actually see anything in it, I have to see it in color. Because it is felt and thought and painted entirely out of color.

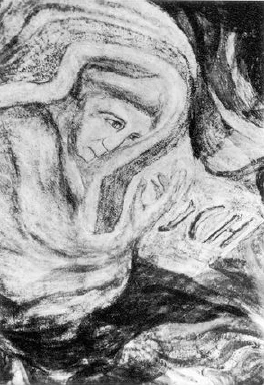

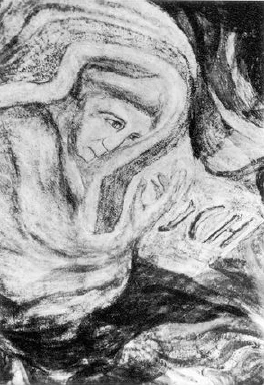

The next picture (Fig. 70): Here you see the only word that appears in the whole structure. There is no other inscription to be found anywhere; everything is meant to be developed into art, into form. But here you will find the “I”. Out of the blue, a kind of fist figure has emerged, that is, the 16th-century human being. The whole cognitive problem of modern man has really emerged from the perception of color before the soul. This cognitive problem of modern man can only be perceived in the abstract, if one perceives as it is often portrayed today; it is different from what we can grasp of natural laws today.

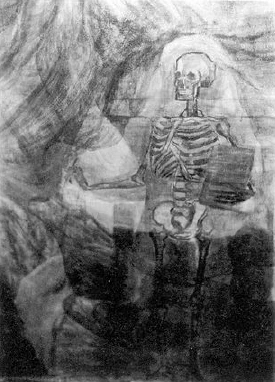

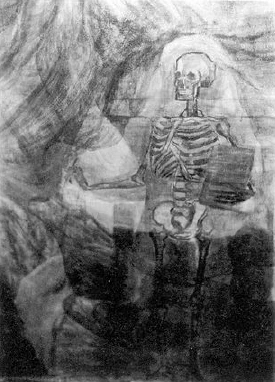

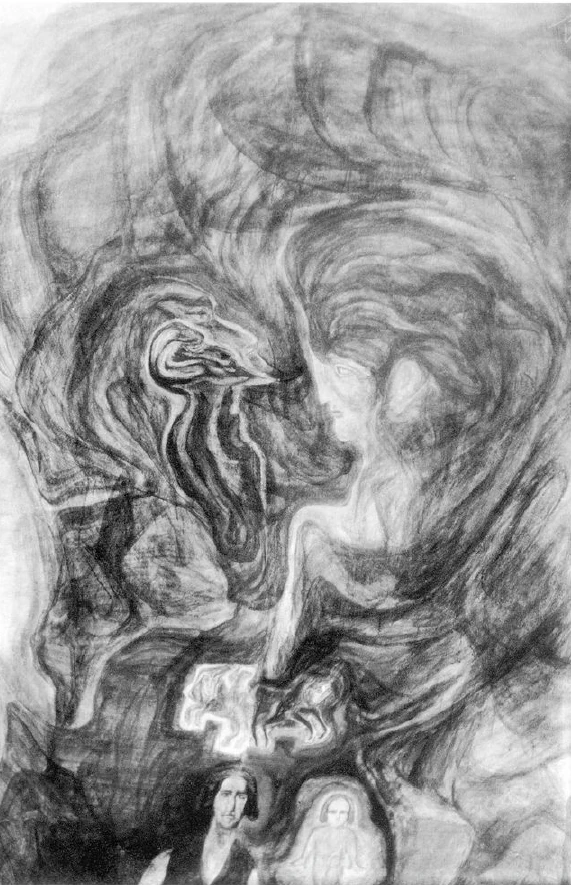

It [the problem of knowledge] intrudes into our soul when we do not merely view things scholastically as abstractions, but when we strive with our whole being to immerse ourselves in the riddles and secrets of the world, as we must in order to be fully human, in order to become aware of our human dignity. Then it places itself beside the striving human being, the one striving for knowledge, who in Faust really, I would say, strives out of the mysterious, mystical blue, strives for the fully conscious I that speaks. The older languages have the I in the verb; for this epoch one is justified in letting a word appear; otherwise there is no word, no inscription or the like in the whole structure, everything is expressed in artistic forms. But the child and birth, and the other end of life, death, are placed alongside the person striving for knowledge. Above it would be the Faust figure you have just seen, below it Death, and further over towards us this flying child. This skeleton here (Fig. 71) in brownish black, in the Faust book in blue, the child (Fig. 72) in various shades of orange and yellow.

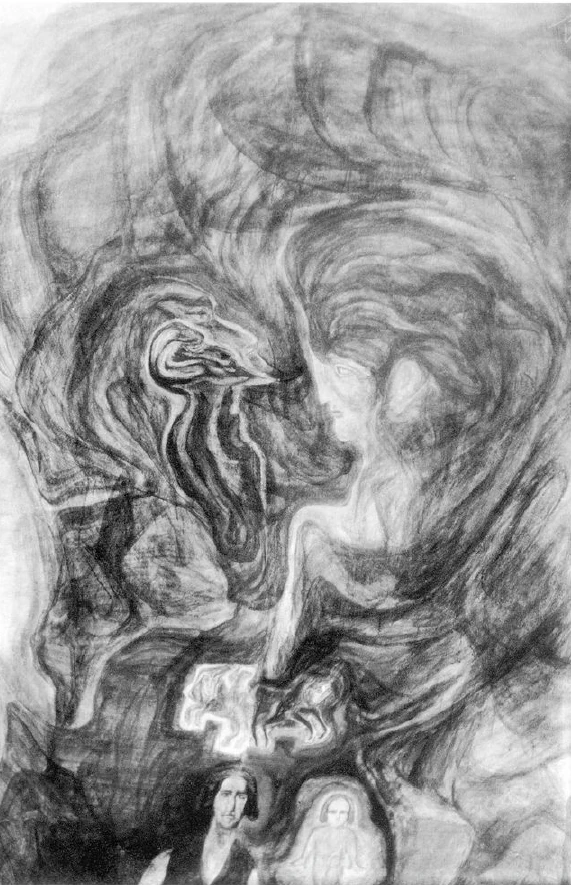

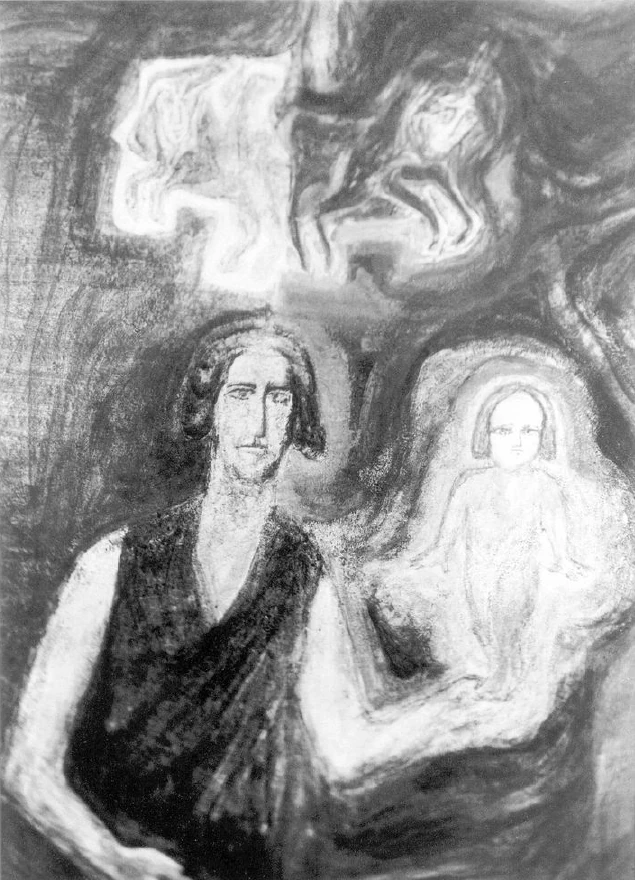

The next picture (Fig. 73): Here you see a compilation: below the skeleton, here Faust, here this child, whom you saw individually, above it a kind of inspirer, an angel-like figure, which I will show as an individual, then other figures join here. As I said, the necessity arose for me to depict the striving of the people of the last centuries from the color surfaces that I wanted to place in just that position. Here then is the striving of the Greeks. You will see it in detail.

The next picture (Fig. 74): the genius in blue-yellow, who is above the fist-shape, as if inspiring the fist-shape from above. We would then come across the striving child. The next picture (Fig. 75): then a kind of Athena figure, taken out of a brownish-orange with light yellow. It is the way in which Greek thinking has become part of the whole world of knowledge and feeling. This figure that we have here is inspired by a kind of Apollo figure, just as Faust was previously inspired by his angel (Fig. 76); this brings us back to Greek thinking.

The next picture (Fig. 76): The inspiring Apollon. Particular care has been taken here with the bright yellow, through which this Apollo figure has been created out of color. I tried to give this bright yellow a certain radiance through the type of technical treatment.

The next picture (Fig. 77): Here you see two figures, which now inspire the Egyptian initiate, who recognizes the tables and feels the world. The man on the right is depicted in a somewhat darker color, I would say a reddish brown, and the Egyptian initiate, who is below him, is also depicted in this way.

The next picture (Fig. 78): The Egyptian knower, that is, the counter-image for those ancient times, which in our case is Faust, who strives for knowledge.

The next picture (Fig. 79): Here you see two figures that I am obliged to always assign certain names to in spiritual science because they keep recurring. One should not think of nebulous mysticism here, but only of the necessity of having a terminology; just as one speaks of north and south magnetism, so I speak of the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic. When we stand face to face with a human being, we cannot grasp his whole being at once, nor with all the powers of knowledge. He has within him two opposing polarities: that which in him constantly strives towards the rapturously false mysticism, false theosophy, that which always seeks to rise above itself towards the unreal , the unfounded, the nebulous - the Luciferic - and that which makes him a Philistine, that which predisposes him to the spirit of heaviness - the Ahrimanic, which is painted here with its shadow. The Luciferic is painted in the yellow-reddish color, the Ahrimanic in the yellow-brownish. It is the dualism of human nature. We can have it physically, physiologically: Then the Ahrimanic in man is everything that ages him, that brings him to sclerosis, to calcification, that makes him ossify; the Luciferic is everything that, when it develops pathologically, brings one to fever, to pleurisy, that thus develops one towards warmth. Man is always the balance between these two. We do not understand the human being if we do not see in him the balance between these two, the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic.

In particular, however, the Germanic-Central European culture that came over Persia is confronted with this duality in its knowledge. Hence the recognizing Central European, who has the child here (Fig. 82) – we will see him in more detail – is inspired by this duality of the Luciferic-Ahrimanic, with which he must come to terms through his inner tragic destiny of knowledge. Here this kind of dualism is seen again in the smaller figure, shaped like a centaur. I painted this during the war, and one sometimes has one's private ideas; the ill-fated fabric of Woodrow Wilson's fourteen points grew out of the abstract transformation of dualism. Here in Switzerland, too, I have repeatedly spoken of the world-destroying nature of these fourteen points: Therefore, I took the private pleasure of immortalizing Mr. and Mrs. Wilson in these figures. But, as I said, this is of little importance.

The next picture (Fig. 81): Here you see the Ahrimanic figure brought out and the shadow above it. In spiritual terms, this is everything that drives man to materialism, to philistinism, to pedantry, what he becomes when – be it expressed in the extreme – he has only intellect and no heart, when all his powers, his soul powers, are directed by the intellect. And if man did not have the good fortune that his outer body is more in balance, his outer body would actually be determined by the soul, he would be an exact expression of the soul: All those people who feel materialistically, feel pedantically, who are almost completely absorbed in the intellect, would look like that on the outside. Of course, they are protected from this by the fact that their body does not always follow the soul, but the soul then looks like this when you see it, when you feel it physically.

Next image (Fig. 80): The Luciferic, worked out of the yellow, worked out of the yellow into the bright. This is what a person develops when he shapes himself one-sidedly according to the visionary, one-sidedly according to the theosophical, when he grows beyond his head; one often finds it developed in some members of other movements who always grow half a meter with their astral head above their physical head so that they can look down on all people. This is the other extreme, the other pole of man.

Here at the bottom, so to speak, is the Germanic initiate (Fig. 82), the Germanic knower in his tragedy, which lies in the fact that duality has a particularly strong effect on him: the Luciferic and the Ahrimanic; as an addition, again, the naivety of the child. This is what emerged for the artistic sensibility. It was worked out of the brown-yellow; the child is kept in the light yellow.

Next picture (Fig. 83): Here we are already approaching the center of the domed room. This man would stand here with the child, and further towards the center are these two figures, which are one. Of course, this does not refer to the current Russian culture or lack of culture, which is corrupting people and the world, but rather the Russian culture actually contains the seed for something future. At present it is overshadowed by what has been imported from the West, by what should indeed disappear from the earth as soon as possible if it does not want to drag the whole of Europe with it into the abyss. But at the bottom of Russian nationality lies something that is guaranteed a future. It should be expressed through this figure, which has its double only here. That which lives in Russian nationality always has something of a double about it. Every Russian carries his shadow around with him. When you see a Russian, you are actually seeing two people: the Russian, who dreams and who is always flying a meter above the ground, and his shadow. All of this holds future possibilities. Hence this characteristic angel figure, painted out of the blue, out of the various shades of blue. Above it, a kind of centaur, a kind of aerial centaur. Here this figure, everything in the indefinite, even the starry sky above this Russian man, who carries his doppelganger with him.

Next image (Fig. 85): We have now passed the center here. This is the same centaur figure – when facing east, located on the left – as the earlier one on the right of the center. This angel figure is the symmetrical one to the one you have just seen. This one, however, is painted in a yellowish orange, and below it would now be the Russian with his doppelganger, but symmetrical to what was shown before.

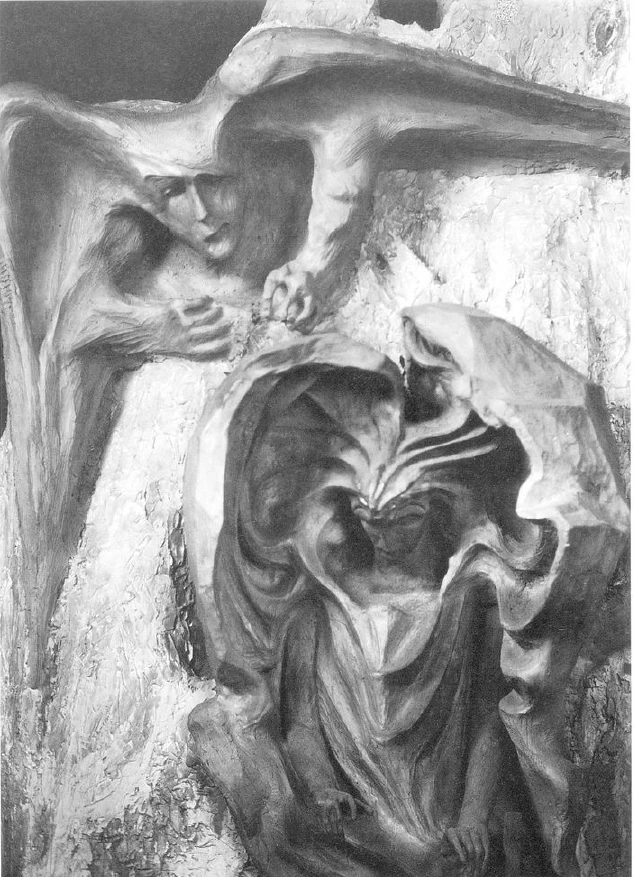

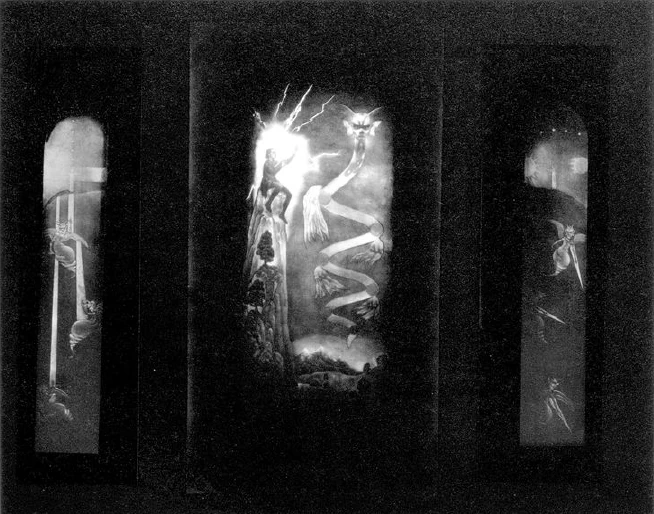

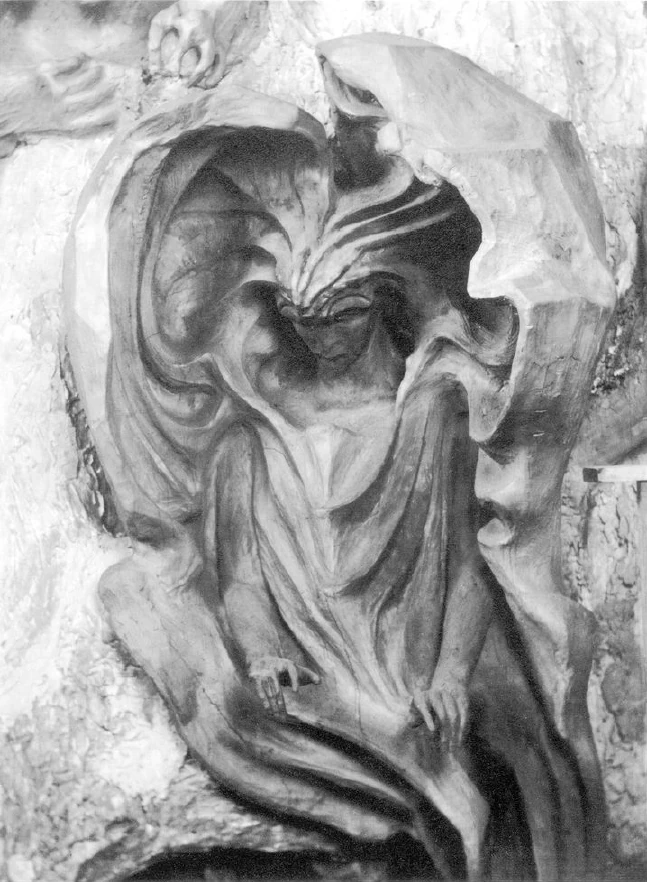

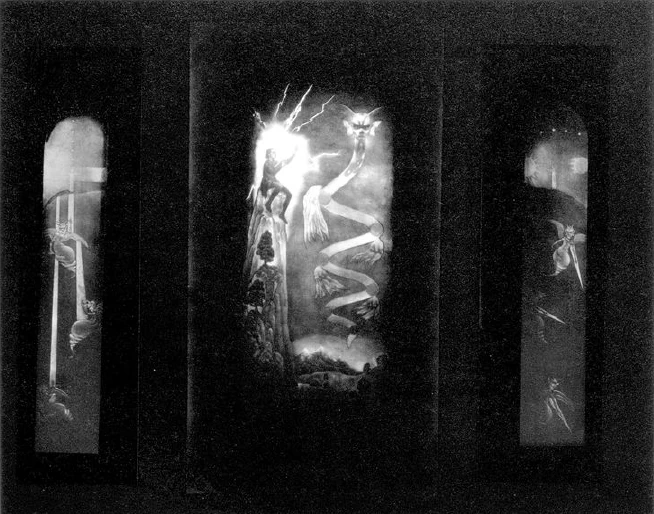

Next image (Fig. 86): Now we are standing in the middle of the small domed room. Once again, on the other side, the Russian motif. Here, you can see the figure of Ahriman lying in a cave; and here, at the top, the representative of humanity. One can imagine him as the Christ. I have formed him out of my own vision as a Christ-figure. Lightning flashes come out of his right hand and surround Ahriman like the coils of a snake. His arm and hand go up to Lucifer, who is painted emerging from the reddish-yellow.

Next image (Fig. 87): Here you can see the figure of Lucifer a little more clearly. Below would be the figure of Christ, reaching up with his arm; this is the face, painted in yellow-red. So it is the Luciferic in man that strives beyond his head, the enthusiastic, that which alienates us from our actual humanity by making us alien to the world, bottomless.

Next image (Fig. 88): Ahriman in the cave. His head is surrounded by lightning serpents that emanate from the hand of Christ, who is standing above them. Here the wing, the brownish yellow, is painted more in the brownish direction, in places descending into the blackish blue.

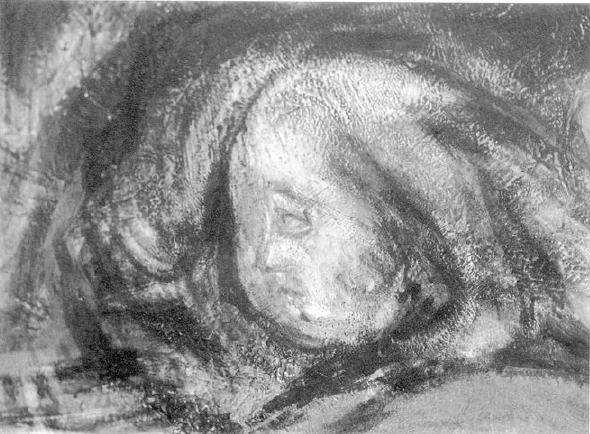

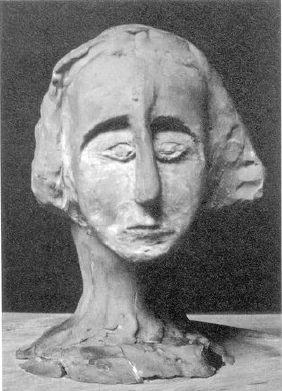

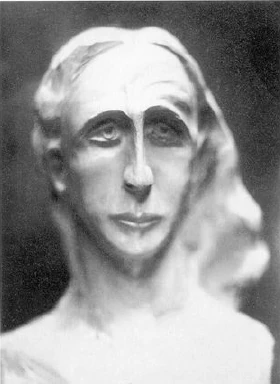

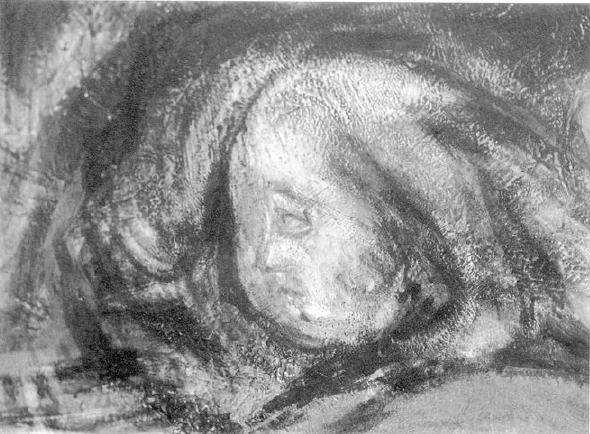

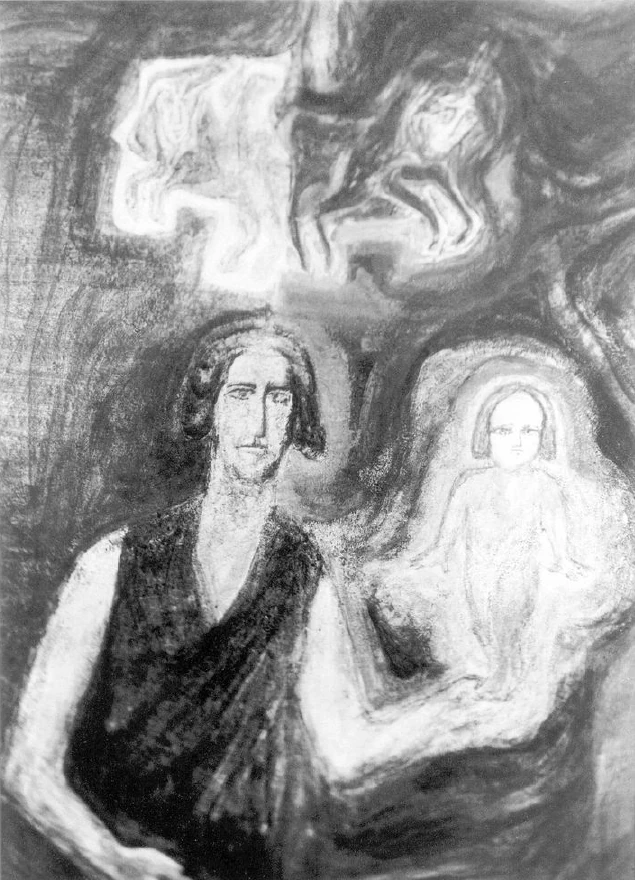

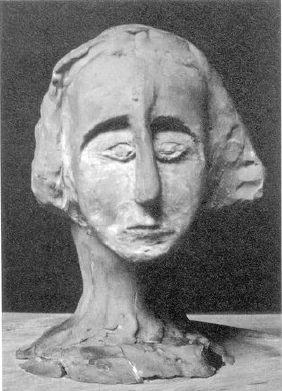

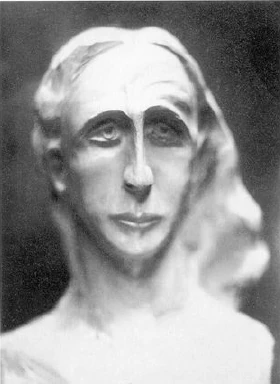

Next picture (Fig. 89): Here I am now showing you my first sketch for the plastic figure of Christ. You see, I tried to make Christ beardless, but Christ pictures have only had a beard since the end of the fifth or sixth century. Of course, no one has to believe me. It is the Christ as he presented himself to me in spiritual vision, and there he must be depicted beardless.

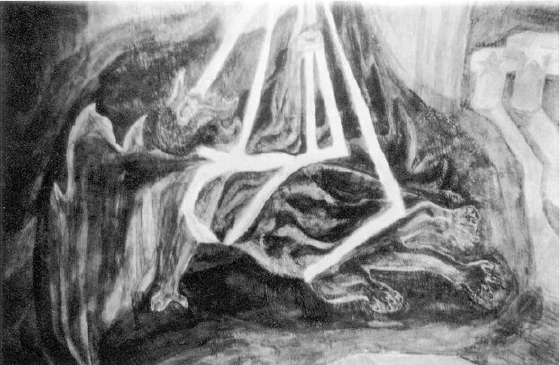

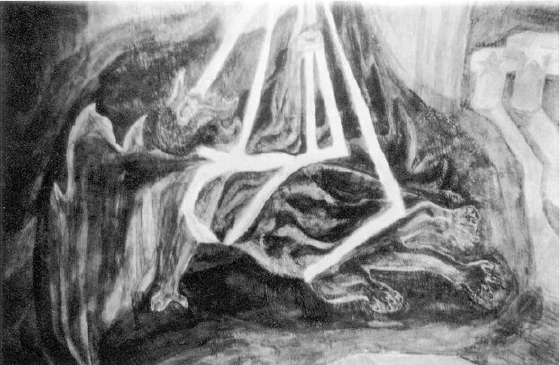

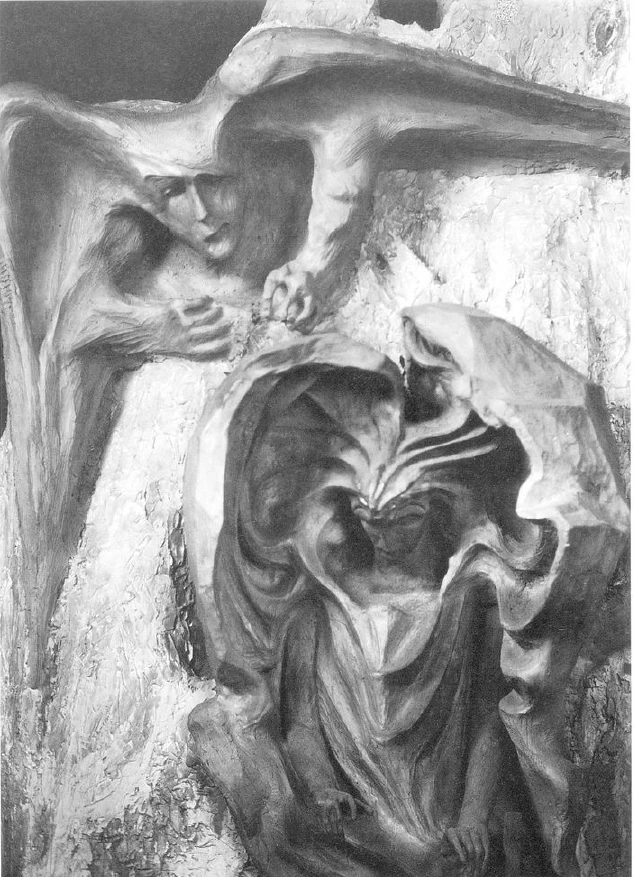

Next image (Fig. 90): The painted head of Christ between Ahriman and Lucifer, the images that I have just shown. Painted in the dome room above is Christ between Ahriman and Lucifer, and below it will later be – it is still far from finished – the nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group (Fig. 93), in the middle of which is the representative of humanity, the Christ, with his right arm lowered and his left arm raised, in such a way that this position, like embodied love, is placed between Ahrimanic and Luciferic forces.

, the Christ, his right arm lowered, his left arm raised, in such a way that this position, like embodied love, is placed between the Ahrimanic and the Luciferic. The Christ does not face the two aggressively. The Christ stands there as the embodiment of love. Lucifer is overthrown not because Christ overthrows him but because he cannot bear the proximity of Christ, the proximity of the being that is the embodiment of love.

Next picture (Fig. 92): This is the first model, made in plasticine, for the Christ, en face, that is, for the representative of humanity, who is to stand in the middle of the wooden group (Fig. 93). But I would like to explicitly note that it will not be somehow obvious that this is the Christ; rather, one will have to feel it from the forms, from the artistic aspect. Nothing, absolutely no inscription, except for the “I” that I mentioned earlier, can be found in the entire structure.

Next image (Fig. 98): This is from the left side of this group of woodcuts [taken from the execution model]: Here is Lucifer striving upwards, and above him a rock creature emerging from the rock, so to speak, the rock transformed into an organ. Here is Lucifer; here Christ would stand; here is the other Lucifer, and that is such a rock creature. It is a risk to make it completely asymmetrical, as asymmetries in general play a certain role in these figures, because here the composition is not conceived in such a way that one takes figures, puts them together and makes a whole – no, the whole is conceived first and the individual is extracted. Therefore, a face at the top left must have a different asymmetry than one at the top right. It is a daring thing to work with such asymmetries, but I hope that it will be felt to be artistically justified if one ever fully comprehends the overall architectural idea.

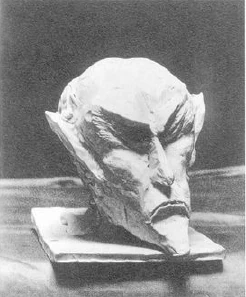

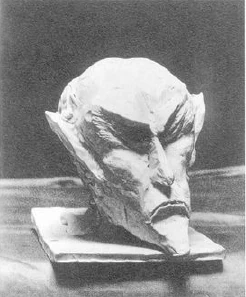

Next image (Fig. 99): Here you can see the model of the Ahriman head. It is the original wax model that I made in 1915. It is an attempt to shape the human face as if the only things present in the human being were the aging, sclerotizing, calcifying forces, or, in the soul, that which makes the human being a philistine, pedant, materialist, which lies in him by being an intellectualizing being. If he had no heart at all for his soul life, but only reason, then he would present this physiognomy. We do not get to know the nature of a human being by merely describing it in the way that ordinary physiology and anatomy do. This one-sided approach provides only a limited insight into the human being. We must move on to an artistic appreciation of form, and only then do we get to know what lives and breathes in a person, what is truly there. You can never get to know the human being, as is attempted in the academies, anatomically or physiologically; you have to ascend to the artistic – that is part of artistic recognition – and must recognize, as Goethe says: “When nature begins to reveal her secrets to him who is open to them, he feels the deepest yearning for her most worthy interpreter, art.” Not only the abstract word, not only the abstract idea and the abstract thought, but also the image gives something of what the forces of nature are, what is really contained in the secrets of nature. One must ascend to the artistic, otherwise one cannot recognize nature. The building may rightly call itself the “Goetheanum” for the reason that precisely such a Goethean understanding of nature also strives for an understanding of the world. Goethe says: Art is a special way of revealing the secrets of nature, which could never be revealed without art.

Next image (Fig. 101): The figure of Lucifer above, here the chest, wing-like. It is the case that one really has to immerse oneself in all of nature's creativity if one wants to give plastic form to something like this figure of Lucifer. Nothing can be symbolized, nothing can be allegorized, nothing can be thought and the thought put into earlier forms, but one must really delve into how nature creates, one must know the nature of the human rib cage, the lungs, one must know the organ of hearing, then the atrophied flight tools that the human being has in his two shoulder blades. All of this must be brought into context, because a person would look quite different if they were not intellectually developed, if the heart did not hypertrophy and overgrow everything: The heart, the hearing organs, wing-like organs, everything would be one. Those who do not merely accept the naturalistic, but also what is ideal, spiritual in the beings, will see in such art only that which reveals the secrets of the world and of existence in the Goethean sense. Up there you can see the hands of this asymmetrical rock creature.

Next image (Fig. 103): Here you can see a building in the vicinity of the Goetheanum. It was originally built to carry out a kind of glass etching. Now it serves as a kind of office space, and eurythmy rehearsals and eurythmy lessons are also given there. In the wooden wall of the large domed room, there are glass windows between every two columns, and these glass windows are not made in the old glass window art, but in a special art, which I would call glass etching. Panes of glass of the same color are engraved with a diamond-tipped stylus that is clamped into an electric machine, and the artist actually works here as an etcher on glass, as he otherwise works as an etcher on a plate, only on a larger scale. So that you scratch out in the monochrome glass plate, thus working the motif in question into the light. This is how we got these glass windows, which have different glass colors, so that there is a harmonious effect. When you enter the building, you first come to one glass color, then to the other, to certain color harmonies. These glass windows had to be ground here; accordingly, this house was built, which, except for the gate and the staircase, is individually designed in every detail. Here we do not have the earlier castles that are otherwise present, but a special form of castle has been used (Fig. 105). So it is individually designed down to the last detail. Next picture (Fig. 104): The gate to this house just shown; below the concrete staircase.

Next image (Fig. 110): Here you see one of these glass windows, which is executed in green. The motifs here are created out of green panes of the same color. The etching is actually only, I would say, a kind of score. This is then a work of art when it is in its place and the sun shines through. So the artist does not finish the work of art, but only a kind of score: when the sun shines through, this etching achieves what, together with the sunbeam shining through, actually creates the work of art. This again marks something that emerges from the whole building idea of Dornach and is physically expressed here.

The Dornach building is built on a fundamentally different architectural idea from other buildings. The walls of the previous buildings are closing walls, artistically also conceived as closing walls. No wall in Dornach is conceived in this way; the walls in Dornach are designed in such a way that they are artistically transparent, so that one does not feel closed in when one is inside the building. All the walls, so to speak, open up through the artistic motifs to the whole great world, and one enters this building with the awareness that one is not in a building but in the world: the walls are transparent. And this is carried out in these glass windows right down to the physical: they are only a work of art when the sun shines through them. Only together with the sunbeam does what the artist has created become artistic.

Next picture (Fig. 113): Another window sample, taken from the same-colored glass pane. The fact that these windows are there means that the room is again illuminated with the harmoniously interwoven rays, and one can, especially when one enters the room in the morning hours, when it is full of sunshine, really feel something through the light effects in the interior, which cannot be called nebulous, but in the best sense inwardness, an impression, an image of the inwardness of the existence of the world and of human beings. For just as, for example, in Greek temple architecture there stands a house that can only be conceived as the house that no human being actually enters, at most the forecourt as a hall of sacrifice, but which is the dwelling place of the god, just as the Gothic building, regardless of whether it is a secular or a church building, is conceived as that which is not complete in itself, but which is complete when it has become a hall for assembly and the community is within it, the whole building idea of Dornach, as I have developed it here in its details, should work so that when a person enters this space, they are just as tempted to be in the space with other people who will look at what is presented and listen to what is sung, played or recited.

Man will be tempted, on the one hand, to feel sympathy with those who are gathered, but the question or the challenge that is as old as Western culture will also arise: know thyself! And he will sense something like an answer to this in the building around him: know thyself. The attempt has been made to express in the building forms, in an artistic and non-symbolic way, that which the human being can inwardly experience.

We have already experienced it: when, for example, an attempt was made to recite - to eurythmy or to recite to oneself - the space that I showed you as the organ room, when an attempt was made to recite into it, or when an attempt was made to speak of the intermediate space between the two dome spaces, the whole room took these things in as a matter of course. Every form is adapted to the word, which wants to unfold recitatively or in discussion and explanation. And music in particular spreads out in these plastic-musical formal elements, which the building idea of Dornach is meant to represent.

In conclusion, I would just like to say, my dear attendees: With these details, which I have tried to make clear to some extent through the pictures, I wanted to present to your souls what the building idea of Dornach should be: a thought that dissolves the mechanical, the geometric, into the organic, into that which itself presents the appearance of consciousness, so that this consciously appearing element willingly accepts that which arises from the depths of human consciousness.

However, this means that something has been created that differs from previous building practices and customs, but in the same way that spiritual science oriented towards anthroposophy also wants to place itself in the civilization of the present day: as something that feels related to the emerging forces of the rising sun, and at the same time wants to strongly oppose the terribly devastating forces of decline of our time. Thus, that which wants to live in the teaching of anthroposophy, the whole world view of anthroposophy, also wants to express itself through the building forms. What is to be heard in Dornach through the spoken word should also be seen in the forms. Therefore, no arbitrary architectural style was to be used, no arbitrary building constructed: it had to grow out of the same spiritual and intellectual background from which the words spoken in Dornach arise. The whole idea behind the building, the whole of the Dornach building, is not to be a temple building, but a building in which people come together to receive supersensible knowledge.

People say that just because one is too poor to find words for the new, one often says: that is a temple building. But the whole character contradicts the old temple character. It is entirely that which is adapted in every detail to what, as spiritual science in the anthroposophical sense, wants to step out into the world. And basically, every explanation is a kind of introduction to the language, to the world view, from which the artistic concept has emerged. I believe that artistically, the building expresses its own essence and content, even if it is still often perceived today as something that is not justified in terms of what is considered acceptable in terms of architectural style, forms and artistic language. Only someone who has already absorbed the impulse, the entire civilizing character of spiritual science, will understand that a new architectural idea had to emerge from this new world view. And as badly as contemporaries sometimes take it, something like this had to be presented, just as anthroposophical spiritual science had to be talked about.

And so, in the manner of a confession, today's discussion, which sought to point to the building of Dornach and to these thoughts, may simply conclude with the words: something was ventured that had not been done before as a building idea, but it had to be ventured. If something like this had not been ventured, had not been ventured at various points in time, there would be no progress in the development of humanity. For the sake of human progress, something must be ventured first. Even if the first attempt is perhaps beset with numerous errors – that is the very first thing that the person speaking here will admit – it must nevertheless be said: something like this must always be ventured again in the service of humanity. Therefore, my dear attendees, it has been ventured out there in Dornach, near Basel.

5. Der Baugedanke Des Goetheanum

Die anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft hat in den letzten Jahren in Dornach bei Basel eine äußere Wirkungsstätte gefunden. Die Entstehung dieser Wirkungsstätte, die sich Goetheanum nennt, Freie Hochschule für Geisteswissenschaft, ergab sich aus dem Gang der Ausbreitung dieser anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft. Nachdem durch eine lange Reihe von Jahren von mir und anderen diese Geisteswissenschaft in den verschiedensten Staaten und Orten zunächst in ideeller Form verbreitet worden ist durch Vorträge oder Ähnliches, stellte sich etwa um das Jahr 1909, 1910 die innere Notwendigkeit heraus, durch andere Offenbarungs- und Mitteilungsmittel, als sie in den bloßen Gedanken und in den bloßen Worten liegen, dasjenige vor die Seelen der Mitmenschen heranzutragen, was mit dieser Geisteswissenschaft gemeint ist. Und so kam es denn dazu, dass aufgeführt wurden — zunächst in München - eine Reihe von Mysteriendramen, die von mir verfasst, in bildhafter, szenischer Form dasjenige geben sollten, wovon anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft ihrer ganzen Wesenheit nach sprechen muss.

Man ist ja gewöhnt worden, durch den ganzen Bildungsgang der zivilisierten Welt in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten, Erkenntnis vorzugsweise zu suchen durch die äußere nliche Beobachtung und durch die Anwendung des menschlichen Intellektes auf diese äußere sinnliche Beobachtung, und im Grunde genommen sind alle unsere neueren Wissenschaften, insofern sie heute noch immer gangbar sind, durch Wirkungen der sinnlichen Beobachtungsergebnisse mit intellektuell Erarbeitetem zustande gekommen. Schließlich kommen auch die historischen Wissenschaften heute auf keine andere Weise zustande. Intellektualismus ist vorzugsweise dasjenige, zu dem die moderne Welt Vertrauen hat, wenn es sich um Erkenntnis handelt. Intellektualismus ist dasjenige, an das man sich dadurch immer mehr und mehr gewöhnt hat.