The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

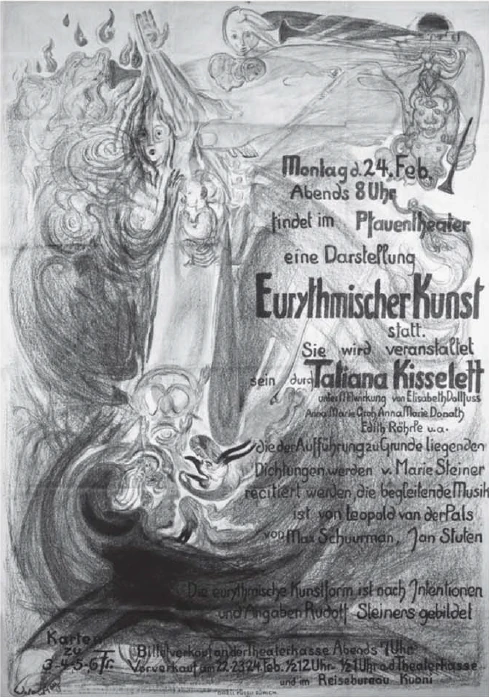

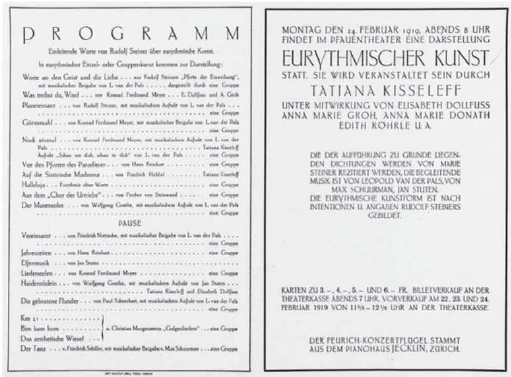

24 Februar 1919, Zurich

Automated Translation

4. Eurythmy Performance

The first public eurythmy performance should have taken place in Zurich and was originally planned for October 1918, but was canceled by the authorities (see the documents on p. 44f.). Instead, it took place on February 24, 1919, carefully prepared by Rudolf Steiner with texts for the announcement in the newspaper and a text for the program booklet. Further public performances followed in 1919 in Winterthur, Stuttgart, Mannheim, Dresden and Bern, as well as public performances at the Goetheanum.

The art of movement known as eurythmy, which has so far only been practiced in a small circle, has its starting point in Goethe's view that all art is the revelation of hidden natural laws that would otherwise remain hidden. This idea can be combined with another, also from Goethe. In every single human organ, one finds a lawful expression of the human form as a whole. Every single limb of the human being is, so to speak, a human being in miniature, just as – in Goethean terms – a plant leaf is a plant in miniature. One can turn this idea around and see in the human being an overall expression of what one of his organs represents. In the larynx and the organs connected with it for speech and song, movements are carried out or even only intended through these activities, and these reveal themselves in sounds or combinations of sounds, while they themselves remain unobserved in ordinary life. It is not so much these movements themselves as the intentions of the movements that are to be realized in eurythmy through the movements of the whole body. The whole human being should make visible, in movement and posture, what imperceptibly takes place in the formation of sounds and tones in a single organ system. Through the movements of the limbs, what takes place in the larynx and neighboring organs when speaking and singing is revealed. Through movement in space and in the forms and movements of groups, what lives in sound and speech through the human soul is depicted. Thus, something is created through this eurythmic art of movement, in the creation of which the impulses that have worked in the development of all art forms have prevailed. All arbitrary mimicry or pantomime, all symbolization of the soul through movements is excluded; expression is achieved through a lawful inner connection, as in music. Eurythmy should lead back to the source of dance as an art form, from which it has, however, become far removed over time. It aims to do this in the sense of a truly modern concept of art, not by imitating or merely restoring an ancient form. It is in the nature of things that the art of eurythmy is connected to the musical. The musical accompaniments to the eurythmy performances that arise in the course of the presentation were provided by van der Pals. What is now being presented as eurythmy is a beginning; the intentions associated with this art will no doubt develop further. However, they should be seen as a start.

Program for the performance in Zurich, February 24, 1919

Dear attendees!

Allow me to say a few words about our performance. This is all the more necessary because, as I may say from the outset, this performance is not about some already completed art form, but about a will, perhaps I could even say: about the basis for a will. And in this sense, I ask you to still perceive and accept our attempt today. We certainly do not want to compete in any way with any dance art form that appears similar to ours or anything of the sort. We know very well that in all these neighboring arts, people are able to present infinitely more perfect performances than we are able to do in our specific field. But for us it is not at all a matter of giving something that already exists in some other form. It is a special form of art, brought forth through movements of the human body, through mutual movements and positions of personalities distributed in groups.

The whole meaning of our eurythmic art is based on Goethe's world view, and specifically on those parts of Goethe's world view that, when absorbed into one's artistic perception, appear to be the most profound and perhaps the most fruitful for the future of artistic development.

Although it may seem theoretical, I would like to say a few words in this regard to explain the groups depicted. It is well known that Goethe was not only active as an artist, but also had deep - unfortunately one cannot say scientific today - science-like insights into the weaving and essence of all natural processes and conditions. And one need only recall how Goethe arrived at the idea of regarding each individual plant organ as a transformation of the other plant organs that occur in the same being, one link of a natural being as a metamorphosis of the other link, but then again the whole plant - and so also transferred to higher organic beings, animals and humans, to see the whole being as a comprehensive metamorphosis of the individual meaningful links. That is what Goethe came to.

If we immerse ourselves in the intuition that lies in this insight into nature, it is possible to translate this insight into artistic feeling and artistic form. This has been attempted here in our eurythmic art for certain artistically designed movements of the human body itself. And this is to be achieved by first observing what Goethe observed in terms of form, and then artistically transforming it into movement.

To summarize, if I want to express what our intention is in this eurythmic art, I would like to say: the whole human being should become a metamorphosis of a single organ, an outstanding and significant organ, the larynx. Just as the human larynx expresses through speech, through sound, that which lives in the soul, so it is possible that if one intuitively grasps the forces that are active in the larynx and its neighboring organs when forming sounds, when forming tones, then one can implement these forces in the movement patterns of the whole human organism. The whole human organism can, so to speak, become a visible larynx, provided that we clearly realize that what the human larynx expresses in words, in sound, in harmony, in the of the sounds and tones, is only the disposition for certain movements within the air masses themselves, in which, after all, that which is word and tone actually comes to its sensory-physical expression.

So I would like to say: We try to express through the whole human organism that which, as a form of creation, sends the movement of the human larynx into an air mass.

Then, what resonates in sound and speech as a mood of the soul, as an inner feeling, what resonates in the artistic shaping of speech in rhythm, in rhyme, in alliteration, in assonance and so on , is to be expressed by forming groups whose individual members add rhythm, purely inner soul mood, weaving of feeling and the like to what the individual personality expresses through its movements.

We have avoided, absolutely avoided, anything that could be merely a momentary expression of what is going on in the soul. Just as our larynx does not express what is going on in the soul in some random, invented movement, but rather in the way in which there is a lawfulness in the larynx in the sequence of sounds and tones, so here in this eurythmic art there is a lawfulness in the sequence of movement. All facial expressions and forms of expression that are merely gestures should be avoided. And I would ask you to regard all facial expressions that appear today as an imperfection that still exists in our art form. We are still not as far along as we would like.

As you can see from these words, our eurythmic art still differs from other similar art forms in that the whole human body is in motion, not just the legs. I would like to say: here, to an outstanding degree, it is not the legs that are used to unfold a dance-like art of movement, but rather the human arms are the main organs for this art of movement.

In this way, we are attempting to demonstrate in our eurythmic art, in a very specific area, the impulse that lies in the Goethean worldview. Anyone who wishes to judge us fairly today must accept what we have to offer as only a very first beginning, which, as a beginning, can only be imperfect. However, they must also bear in mind that our habits of artistic reception are opposed to what actually works as the most essential in our eurythmic art. Here nothing is a momentary expression, but everything is subject to an inner lawfulness, which is based on an intuitive study of the movement possibilities of the human organism, just as in music itself the succession of tones is subject to a lawfulness, just as in speaking, in making verse, the succession of sounds and words is subject to a very specific lawfulness, so that nothing can arise from momentary arbitrariness in this eurythmic art, but when two people, who are perhaps very different in their individuality, present something in eurythmic art, or when two different groups present something, then the diversity can only go as far as the diversity of interpretation between different piano players playing one and the same Beethoven sonata. It is therefore important that everything subjective, everything arbitrary, be excluded from our eurythmic art.

In allowing myself to say a few words in advance, I ask you to recognize that you are well aware that this is just the beginning, a very modest beginning in our eurythmic art, which we believe is capable of further perfection. And so we ask you to take what we can present with all the forbearance possible in such matters. If you treat us in this way, we hope that after this first attempt our strength will grow and that we – or perhaps others – will one day be able to achieve something better in this field of art forms than we already can.

4. Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Die erste öffentliche Eurythmie-Aufführung hätte in Zürich stattfinden sollen und war ursprünglich für den Oktober 1918 geplant, war aber behördlicherseits abgesagt worden (siehe die Dokumente S. 44f.). Stattdessen fand sie dann am 24. Februar 1919 statt, von Rudolf Steiner sorgfältig vorbereitet mit Texten für die Ankündigung in der Zeitung und einem Text für das Programmheft. - Es folgten 1919 weitere öffentliche Darstellungen in Winterthur, Stuttgart, Mannheim, Dresden und Bern sowie öffentliche Aufführungen am Goetheanum.

Die als Eurythmie bezeichnete Bewegungskunst, die bisher nur in einem engeren Kreise gepflegt wurde, hat ihren Ausgangspunkt von der Anschauung Goethes genommen, dass alle Kunst die Offenbarung ist verborgener Naturgesetze, die ohne solche Offenbarung verborgen blieben. Mit diesem Gedanken lässt sich ein anderer, ebenfalls Goethe’scher, verbinden. In jedem menschlichen Einzelorgane findet man einen gesetzmäßigen Ausdruck der menschlichen Gesamtform. Jedes einzelne Glied des Menschen ist gewissermaßen ein Mensch im Kleinen wie - goethisch gedacht - das Pflanzenblatt eine Pflanze im Kleinen ist. Man kann diesen Gedanken umkehren und im Menschen einen Gesamtausdruck dessen schen, was eines seiner Organe darstellt. Im Kehlkopf und den Organen, die im Sprechen und Singen mit ihm verbunden sind, werden durch diese Betätigungen Bewegungen ausgeführt oder auch nur intendiert, die sich in Lauten oder Lautverbindungen offenbaren, während sie selbst im gewöhnlichen Leben unbeobachtet bleiben. Weniger diese Bewegungen selbst als vielmehr die Bewegungsintentionen sollen nun durch die Eurythmie umgesetzt werden in Bewegungen des Gesamtkörpers. Durch den ganzen Menschen soll sich als Bewegung und Haltung sichtbar machen, was sich im Bilden der Laute und Töne in einem einzelnen Organsysteme unwahrnehmbar abspielt. Durch Bewegungen der Glieder am Menschen kommt zur Offenbarung, was sich im Sprechen und Singen im Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen vollzieht; in der Bewegung im Raume und in den Formen und Bewegungen von Gruppen wird dargestellt, was durch das Menschengemüt in Ton und Sprache lebt. Dadurch ist mit dieser eurythmischen Bewegungskunst etwas geschaffen, bei dessen Entstehung die Impulse gewaltet haben, die in der Entwickelung aller Kunstformen gewirkt haben. Alles willkürlich Mimische oder Pantomimische, alles Symbolisieren von Seelischem durch Bewegungen ist ausgeschlossen; der Ausdruck wird durch einen gesetzmäßigen inneren Zusammenhang erreicht wie in der Musik. Wovon im Wesen des Künstlerischen die Tanzkunst einmal ihren Ausgang genommen hat, wovon sie aber im Laufe der Zeit sich weit entfernt hat, darauf soll die Eurythmie wieder zurückführen. Sie will dies aber im Sinne einer wahrhaft modernen Kunstauffassung, nicht durch Nachahmung oder bloße Wiederherstellung eines Alten. Es liegt in der Natur der Sache, dass die eurythmische Kunst sich verbindet mit dem Musikalischen. Die im Verlaufe der Darstellung auftretenden musikalischen Beigaben zu den eurythmischen Aufführungen hat van der Pals geliefert. Was jetzt schon als Eurythmie auftritt, ist ein Anfang; die mit dieser Kunst verbundenen Absichten werden wohl eine weitere Entwickelung finden. Sie möchten aber als ein Anfang genommen werden.

Programm zur Aufführung Zürich, 24. Februar 1919

Sehr verehrte Anwesende!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich unserer Aufführung einige wenige Worte vorausschicke. Dies wird umso notwendiger sein, als es sich bei dieser Aufführung durchaus, wie ich von vornherein bemerken darf, nicht um irgendeine schon vollendete Kunstform handelt, sondern um ein Wollen, vielleicht könnte ich sogar sagen: um die Anlage zu einem Wollen. Und in diesem Sinne bitte ich Sie, diesen unseren heutigen Versuch noch aufzufassen und aufzunehmen. Wir wollen durchaus nicht mit irgendeiner, unserer Kunstform scheinbar ähnlichen Tanzkunstform oder dergleichen in irgendeiner Weise konkurrieren. Wir wissen sehr gut, dass man in allen diesen Nachbarkünsten unendlich viel Vollkommeneres in der Gegenwart darzubieten versteht, als wir noch auf unserem speziellen Gebiete können. Doch handelt es sich für uns auch gar nicht darum, irgendetwas zu geben, was in irgendeiner anderen Form schon da ist. Es handelt sich um eine besondere Form von Kunst, hervorgebracht durch Bewegungen des menschlichen Körpers, durch gegenseitige Bewegungen und Stellungen von zu Gruppen verteilten Persönlichkeiten.

Der ganze Sinn dieser unserer eurythmischen Kunst fußt auf der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung, und zwar gerade auf denjenigen Teilen der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung, die, wenn man sie in seine künstlerische Empfindung aufnimmt, wohl [als] die grundtiefsten und für die Zukunft der künstlerischen Entwickelung vielleicht fruchtbarsten erscheinen.

Wenn es auch theoretisch aussieht, so darf ich zur Erläuterung der darstellenden Gruppen in dieser Beziehung vielleicht einiges bemerken. Es ist ja in weitesten Kreisen bekannt, wie Goethe nicht nur als Künstler tätig war, sondern wie er tiefe - leider darf man heute nicht sagen wissenschaftliche - wissenschaftsähnliche Einblicke in das Weben und Wesen all der Naturvorgänge und Naturbedingungen getan hat. Und man braucht nur zu erinnern, wie Goethe zu der Vorstellung gelangt ist, jedes einzelne Pflanzenorgan als eine Umwandelung der anderen Pflanzenorgane, die an demselben Wesen vorkommen, anzusehen, das eine Glied eines natürlichen Wesens als eine Metamorphose des anderen Gliedes, dann aber wiederum die ganze Pflanze - und so auch auf höhere organische Wesen, Tiere und Menschen übertragen das ganze Wesen als eine zusammenfassende Metamorphose der einzelnen bedeutungsvollen Glieder anzusehen. Dazu war Goethe gekommen.

Durchdringt man sich mit dem, was für die Intuition in dieser Natureinsicht liegt, so ist es möglich, diese Einsicht in künstlerische Empfindung und künstlerische Gestaltung umzusetzen. Das ist versucht worden hier in unserer eurythmischen Kunst für gewisse künstlerisch ausgestaltete Bewegungen des menschlichen Körpers selbst. Und zwar soll das dadurch erreicht werden, dass das, was Goethe angeschaut hat zunächst für die Form, hier künstlerisch umgesetzt wird in Bewegung.

Wenn ich zusammenfassend ausdrücken will, was eigentlich in dieser eurythmischen Kunst unsere Absicht ist, so möchte ich sagen: Der ganze Mensch soll werden zu einer Metamorphose eines einzelnen Organes, eines allerdings hervorragenden, bedeutungsvollen Organes, des Kehlkopfes. - So wie der menschliche Kehlkopf durch das Wort, durch den Ton ausdrückt dasjenige, was in der Seele lebt, so ist es möglich, dass, wenn man intuitiv erfasst die Kräfte, die im Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen bei der Lautformung, bei der Tonformung wirksam sind, wenn man diese Kräfte intuitiv fasst, so kann man sie umsetzen in Bewegungsformen des ganzen menschlichen Organismus. Der ganze menschliche Organismus kann gewissermaßen ein sichtbarer Kehlkopf werden, wobei man sich nur klar vor Augen halten muss, dass dasjenige, was der menschliche Kehlkopf zum Ausdrucke bringt in Wort, in Ton, in der Harmonie, in der gesetzmäßigen Aufeinanderfolge der Laute und der Töne, dass das nur die Anlage zu gewissen Bewegungen innerhalb der Luftmassen selber ist, in denen ja eigentlich dasjenige, was Wort und Ton ist, zu seinem sinnlich-physischen Ausdrucke kommt.

So möchte ich sagen: Das, was als Gestaltungsform die Bewegung des menschlichen Kehlkopfes hineinschickt in eine Luftmasse, das versuchen wir durch den ganzen menschlichen Organismus zum Ausdruck zu bringen.

Dann soll auch dasjenige, was Ton und Rede durchklingt als Seelenstimmung, als innere Empfindung, was erklingt in der künstlerischen Gestaltung der Rede in Rhythmus, in Reim, in Alliteration, in Assonanz und so weiter, das soll nun zum Ausdruck dadurch kommen, dass wir Gruppen bilden, deren einzelne Glieder eben Rhythmus, rein innere Seelenstimmung, Weben der Empfindung und dergleichen zu dem noch hinzufügen, was die einzelne Persönlichkeit durch ihre Bewegungen zum Ausdruck bringt.

Vermieden, wesentlich vermieden ist bei uns alles dasjenige, was irgendwie nur ein augenblicklicher Ausdruck wäre desjenigen, was in der Seele vorgeht. So wie unser Kehlkopf nicht in irgendeiner augenblicklichen, erfundenen Bewegung zum Ausdrucke bringt, was in der Seele vorgeht, sondern so, wie im Kehlkopf eine Gesetzmäßigkeit gegeben ist in der Aufeinanderfolge der Laute und der Töne, so ist hier in dieser eurythmischen Kunst eine Gesetzmäßigkeit gegeben in der Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegung. Alle Mimik, alle Ausdrucksform, die bloß in der Geste liegen, sollen vermieden werden. Und alle Mimiken, wo sie heute auftreten werden, da bitte ich Sie, dies noch als in unserer Kunstform bestehende Unvollkommenheit aufzufassen. Wir sind noch durchaus nicht so weit, als wir schon gerne wären.

Von anderen ähnlichen Kunstformen unterscheidet sich ja, wie Sie aus diesen Worten schon werden entnehmen können, unsere eurythmische Kunst noch dadurch, dass der ganze menschliche Körper, nicht bloß etwa die Beine, in Bewegung kommt. Ich möchte sagen: Es wird hier in besonders hervorragendem Maße gar nicht mit den Beinen eine tanzartige Bewegungskunst entfaltet, sondern die Hauptorgane für diese Bewegungskunst sind gerade die menschlichen Arme.

So versuchen wir auf einem ganz bestimmten Gebiete dasjenige, was als Impuls in der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung liegt, in unserer eurythmischen Kunst vorzuführen. Derjenige, welcher uns heute richtig beurteilen will, muss dasjenige, was wir bieten können, durchaus nur als einen allerersten Anfang, der als Anfang nur unvollkommen sein kann, aufnehmen. Er muss aber auch berücksichtigen, dass jene Gewohnheiten des künstlerischen Aufnehmens solcher Dinge entgegenstehen demjenigen, was in unserer eurythmischen Kunst eigentlich als das Wesentlichste wirkt. Hier ist nichts eben augenblicklicher Ausdruck, sondern alles ist einer innerlichen Gesetzmäßigkeit unterworfen, die auf einem intuitiven Studium der Bewegungsmöglichkeiten des menschlichen Organismus beruht, wie in der Musik selbst die Aufeinanderfolge der Töne einer Gesetzmäßigkeit unterworfen ist, wie im Sprechen, im Versemachen die Aufeinanderfolge der Laute und Worte einer ganz bestimmten Gesetzmäßigkeit unterworfen ist, sodass niemals irgendetwas aus augenblicklicher Willkür bei dieser eurythmischen Kunst entstehen kann, sondern wenn zwei Menschen, die vielleicht in ihrer Individualität schr verschieden voneinander sind, in eurythmischer Kunst etwas darstellen, oder zwei verschiedene Gruppen etwas darstellen, so kann die Verschiedenheit nur so weit gehen, wie etwa die Verschiedenheit der Auffassung verschiedener Klavierspieler, die eine und dieselbe Beethovensonate spielen. - Es handelt sich also darum, dass alles Subjektive, alles Willkürliche aus unserer eurythmischen Kunst ausgeschaltet ist.

Indem ich mir erlaubt habe, diese paar Worte vorauszuschicken, bitte ich Sie, dass Sie erkennen, dass Sie durchaus wissen, dass es sich durchaus um einen Anfang nur handelt, um einen schwachen Anfang bei unserer eurythmischen Kunst handelt, von dem wir allerdings glauben, dass er einer weiteren Vervollkommnung fähig ist. Und so bitten wir Sie, das, was wir darstellen können, mit aller Nachsicht, die in solchen Dingen möglich ist, aufzunehmen. Wenn Sie uns so behandeln, dann hoffen wir, dass nach diesem ersten Versuch unsere Kräfte wachsen und wir - oder vielleicht andere einmal - auf diesem Gebiete in solchen Kunstformen auch etwas Besseres leisten können als schon heute.