Earthly Knowledge and Heavenly Wisdom

GA 221

17 February 1923, Dornach

VI. Moral Impulses and Physical Effectiveness in Human Beings. The Comprehension of a Mental Process. (continued)

Yesterday, using Nietzsche as an example, I tried to show how a person who lives entirely in the external world of today's civilization, and yet, like Nietzsche, wants to seek moral impulses from human nature, must fail because it is impossible to find out from the present-day way of knowing how moral impulses intervene in physical life. Today we have a civilization that, on the one hand, accepts the laws of natural science and shapes our education accordingly, so that from childhood we absorb views about the interrelationships in nature. On the other hand, we have a moral world view that stands on its own. We understand moral impulses as commandments or as conventional rules of conduct that arise in the context of social human life. But we cannot conceive of the moral life on the one hand and the physical life on the other as being intimately connected. And yesterday I pointed out how Nietzsche, starting from what he made his supreme virtue, from honesty, from honesty towards himself and others, ultimately came to accept only the physical in man, and then to let the moral emerge from the physical, which he perceived as the humanly all-too-human. Because he wanted to be honest with the world view of his time, his moral philosophy failed because he could not see how the moral and the physical interact in one.

This interaction cannot be seen either unless one enters into that realm which, in the right sense, is called the supersensible. One must be clear about the fact that only in human life itself is contact established, as it were, between what one feels as moral impulses, between moral ideals for my sake, and the physical activity, the physical processes in the human being itself. And the big question today is this: when I have a moral impulse, does it remain something quite abstract, or can it intervene in the physical organization?

I told you yesterday: When we stand before a machine, we can be sure that a moral impulse will not intervene in the workings of the machine. There is initially no connection between the moral world order and the mechanism of the machine. If, as is increasingly the case in the modern scientific world view, the human organism is also depicted in a machine-like way, then this also applies to humans, and moral impulses remain illusions. At most, man can hope that some being, given to him through a revelation, will intervene in the moral order of the world, rewarding the good and punishing the bad; but he cannot somehow see a connection between moral impulses and physical processes from within the world order itself.

Today, I would like to point out the area in which this connection between what a person experiences within themselves as moral and the physical really occurs. To better understand the explanations that I will give, let us first take the animal.

In the animal, we have an interaction of the physical organism, an etheric formative forces organism and the astral organism. The actual I is not directly embodied in the animal organization itself, but intervenes from the outside as a group I in the animal organization. Now, with the animal, we must be clear about the fact that two directions can be clearly distinguished in its organization. We see the animal head. In the higher animals, as in man, the head is the most excellent carrier of the nervous-sensory organism. We see how everything that the animal takes in from the external sensory world essentially penetrates the animal through the organs of its head.

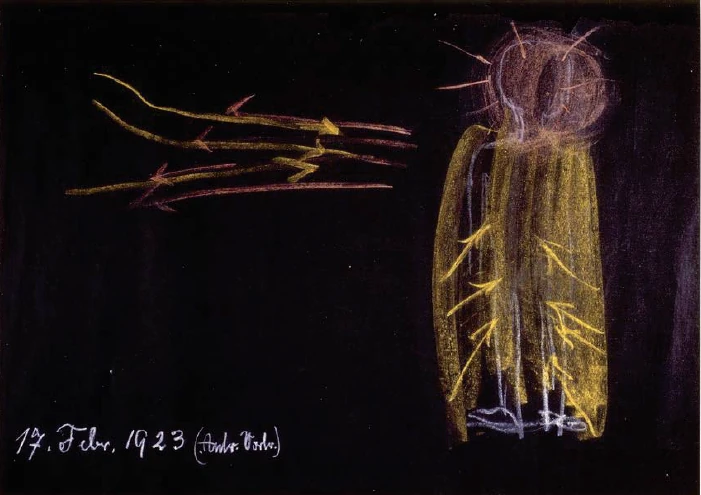

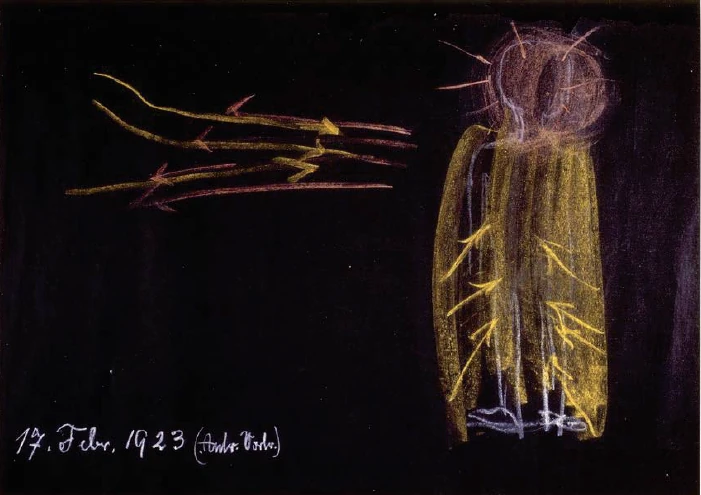

What I have emphasized again and again is certainly true: we cannot directly relate the structure of an organism to a physical part of it. We have to say: the animal is entirely head in a certain respect, because it can perceive all along its body. But the animal is primarily a nerve-sense organism at the head. This is where it effects its relationship to the external world. If we then look at the animal in its overall organization, in that we see it in relation to the rest of its organism, how it has, as it were, the other pole of the head organization towards the tail end, then, when we look at the structure of the animal in its physical, etheric and astral organization, we have the matter in such a way that, as it were, the astral mobility of the animal flows from back to front. The astral currents, the currents of its astral organism, constantly flow from back to front, and they encounter the impressions that the senses experience at the head. So that we have an intermingling from back to front and from front to back in the animal. I would like to draw this interflow schematically in such a way that the astral currents in the animal flow from back to front (red arrows), and that the sense impressions flow from the head to the back (yellow arrows). Between these two currents, there is an interaction in the animal that extends throughout the entire organism.

You can clearly see this interaction in the dog. The dog sees its master and wags its tail. When the dog sees its master and wags its tail, this means that it has the impression of its master, and that the astral current flows from the inside towards this impression, which goes from front to back, from the outside. And this flowing towards the tail from the whole organism from back to front is expressed in the dog's wagging. There is a complete coming together. And anyone who wanted to ask about the dog's physiognomy when it expresses joy should not so much look at the dog's face when it looks at its master, but should consider the wagging of the tail: there is a physiognomy in that.

This is basically the case with every animal. Only, let us say, when we go down to the fish, it is not noticed so much because the astral body has a great deal of independence there. But for the observing consciousness it is all the more vivid. It becomes quite clear to the observing consciousness that when the fish perceives something through its nervous-sensory apparatus, which comes towards it in the current, it itself sends its own astral current from behind towards the front, and then there is a wonderful interlocking of what the fish sees and what it brings. This intimate interlocking of the astral current from outside – for it is an astral current from outside that a being receives with the sense impressions – and the astral current from behind to the front is interrupted in the human being by the fact that the human being is an upright being.

Because man is an upright being, he is not able to send the astral current directly towards the sense impressions in the same way as a dog, for example. The dog has a horizontal spine. The astral movement from back to front passes directly through its head. In man the head is raised. Thus the whole relationship of those astral currents that flow from back to front, which make up the actual inner being, the harmony of these currents with those currents that come through the sense impressions, is not as simple as it is in the animal. And especially as regards the moral nature of man, one must study exactly what I have just assumed in order to understand the intervention of the moral in the physical in man. With animals we do not speak of morality because in the animal world this streaming of the astral from behind to the front and from the front to the back is uninterrupted. In man the following occurs.

The human being raises his head out of the astral current that comes from him and goes from behind to in front. This raising of the head signifies the embodiment of the actual self. The fact that the blood does not just take the horizontal path, but that the blood must flow up as a carrier of the inner ego forces, makes that the human being experiences this ego as his ego, as his individual ego. But it also means that in the human being, the head, the main seat of sensory impressions, is purely devoted to the outside world. In fact, the human being is much more organized in such a way that he has a looser connection between his sense of touch and his sense of sight than the animal. In the animal, the sense of touch and the sense of sight are more intimately connected. When the animal sees something, it immediately feels what it sees. The organs of touch are also stimulated by sight. This stimulation of the organs of touch then comes together, in particular, with the current that goes from back to front. In humans, the head is raised and purely devoted to the external world. This is particularly evident in the sense of sight. One might say that the human sense of sight is a kind of etheric sense. We only gradually learn to assess, through our judgment, what distances or the like are in the physical world. As human beings, we see primarily what is expressed in color and in the shades of color.

Consider only that it was only in the time when intellectualism was born that man also began to use perspective in painting. You won't find spatial perspective in the older painters, because only in this period, through the detour of judgment, of intellectualism, have the eyes become accustomed to seeing that which is real, which expresses itself in perspective, that is, in distances.

The eye is primarily for color, light and dark, and gradations of light and dark. But this – in that it is spread over the objects – actually comes from outer space. The sun sends forth light, and in that the light that comes from outer space falls on the things of the earth and is reflected back, the eye actually sees the things not with the help of earthly powers, but with the help of cosmic, of world powers.

But this is symptomatic of the human head in general. It is more devoted to the ethereal world than to the physical. Man actually finds his way into the physical world by walking around in it, by touching it. But he finds his way into the physical world less through the senses of his head.

Just think how ghostly the world would be, how ethereally ghostly, if we did not grasp space through the sense of touch, but if we only grasped what the eye transmits to us about space! The animal organization in relation to the head is quite different from the human organization. The animal organization is much more closely connected with physical reality through the head than is the human organization. When man takes the perceptions of his head, he has something ideal in it because it is ethereal. He actually lives entirely in the etheric world through his head.

Now the head is also external – and this is not something merely superficial that I am mentioning – but the head is also externally reproduced in man according to the cosmos. Take the individual animal head formations. They are directly an expression of the animal's own physicality. You cannot find that cosmic roundness of the formation of the head in animals. Man is indeed an image of the cosmic-spherical in his head, and he struggles to achieve this image of the cosmic-spherical by having not the horizontal but the vertical to his bodily line; by rising from the horizontal to the vertical.

This is particularly evident when we consider the whole organization of the human being. The physical organization of the human head is bound to an etheric organization that truly reflects the purity of the cosmos. Throughout a person's earthly life, the organization of the human head in the etheric body is something that is rarely touched by the earthly, but which remains thoroughly cosmic in its etheric and even more so in its astral. It is also the case that when a person passes from one earthly life to the next, the organization that lies outside of his head, that is, what is below his head (the head loses itself as a system of forces after death), is transformed, not the physical matter of course, but the context of forces, is metamorphosed and becomes the head in the next incarnation, in the next earthly life. Thus, in order to become an organization of the head, the human organization must first pass through the cosmos. The human organization of the head cannot develop at all on earth. Through his head, man is completely devoted to the cosmic, only through the rest of his organization is man bound to the earthly. Therefore, we can say: In the animal, the entire configuration of the head arises from the rest of its organization, while in the human being, the head stands out with a certain independence from the rest of the organization. This remaining organization, however, is expressed in the human being's head in everything that becomes a gesture and facial expression. If you have an inner agitation, let us say a feeling of fear, that which lies within the metabolic area, in the blood circulation system, is expressed by the forces of the human organism in the paleness of the face and in the play of expressions. And it is similar with other inner agitations. We see in the human being what is in the rest of the organism, pouring into the head spiritually and mentally, but astrally, and what lives astrally in the rest of the organism is expressed physiognomically, one might say, in the movement of the facial muscles, in the skin coloration, but especially in the play of expressions in the head.

It is a very interesting study when, for example, we see how a person accompanies what he speaks – which of course comes from his I – with a certain facial expression, how what lives in his astral body is expressed in his face. If you look at a person's face as they speak, you receive their thoughts with the words they utter and the accompanying processes in their astral organism with their facial expressions. But the etheric organism of the head is also connected with this astral organism of the head, and this etheric organism of the head is a wonderful reflection of the cosmos. It is a very remarkable experience to observe a person speaking by means of supersensible vision. We see how the astral organism is everywhere manifested in the play of expression, but how the etheric organism of the head is little affected by it. The etheric organism of the head resists the entry of the play of expression into its own formation. It is very interesting to see that certain hymn-singing, for example, in which the human being is imbued with a sense of holiness in his astral body, are easily absorbed into the etheric body of the head, and in fact the etheric body shows a play of light on the side facing the face with every expression; but in the parts situated further back, the etheric body shows a sharp resistance to the absorption of any processes from the expression.

From this you can see that although the human head is related to the rest of the organism, this relationship is subject to certain laws because the etheric body is modeled on the cosmos and wants to remain in this configuration of the cosmos, not wanting to be distracted, especially not by what comes from the passions, the drives, the instincts of human nature.

Now there is something else that is highly significant. In the countenance, we see a certain play of expression that manifests itself outwardly in man. This play of expression depends on the temperament, the character of the person, and on various mental and physical peculiarities. But there is another play of expression in man, even a much more lively play of expression, only this play of expression is not in his consciousness, but in the subconscious. It is extrasensory in nature. It lies in a realm that man cannot reach with his sensory observation. If you look at the human being's astral body, not as it belongs to the head, but as it belongs to the metabolism-limb-organism, if you look at the human being's astral body as it encompasses and permeates the legs, how it encompasses and permeates the abdomen, then, in this part of the astral organism, if you have supersensible vision, you also get to see a play of expression, a very lively play of expression, a physiognomy that is expressed there. And the strange thing is that this play of features, this physiognomy, reveals itself from the outside in. So while the play of features that expresses human speech or the human aspect in the environment reveals itself to the outside, a play of features that the human being does not have in his ordinary consciousness reveals itself to the inside. This is a very interesting fact.

I would like to show you this schematically. Suppose you have the human being here. Then we have the astral body (red), which is the cause of the play of expression and reveals itself to the outside. We have the same astral body, but a different part of it here (yellow), and while here (above) in this astral body we have the play of expression revealing itself outwardly, here (below) we have a play of expression that reveals itself entirely inwardly: this part of the astral body, so to speak, turns its face inward. The human being is unaware of this in ordinary consciousness, but it is so. When we look at a child, we find that this part of the astral body is constantly turning its expression inward, and when we look at more adult people, the expressions even become more or less permanent. The human being takes on an inward physiognomy. And what is this facial expression? Yes, this facial expression is based on the following.

If a person has an impulse for what in everyday life, and rightly so, is called a good deed, a moral deed, then the play of expression within is different than when one has an impulse for an evil deed. There is, as it were, an ugly expression, an ugly facial expression, if I may say so, inwardly, when a person performs an egoistic act. For basically all moral acts reduce themselves to the non-egoistic, all immoral acts to the egoistic. The only difference is that in ordinary life this true moral judgment is masked by the fact that someone can actually be very immoral, namely thoroughly permeated with selfish motives, but conventionally follows certain moral rules. These are then not his own at all. He is integrated into what he has been raised in, or what he does because he is embarrassed about what others will say. He is threaded in as a link in a chain. But the truly moral, which actually adheres to human individuality and lives in it, is already such that the good comes from the interest that we have in the other person; from the interest that we can gain from we can feel what others feel and experience as our own, while the immoral is something that originates in the fact that the human being closes himself off, where he does not empathize with what other people feel. To think good is basically to be able to put yourself in other people's shoes, to think evil is not to be able to put yourself in other people's shoes. This can then become a law, a conventional rule, something that one is or is not ashamed of. Then what is actually selfish can be greatly suppressed by convention. But basically, it is not what a person does that is decisive for the moral evaluation; rather, one must look deeper into the human character, into human nature, in order to be able to judge the actual moral value of the person.

The moral value expresses itself in the astral body in that this part of the astral body turns a beautiful countenance inward when unselfish actions and altruistic impulses live in the person, and an ugly facial expression inward when selfish, evil impulses live in the person. So that a spirit who reads inside the [astral] person can judge exactly the same way by this physiognomy whether a person is good or evil, as one can judge the person by other characteristics of his facial expressions. All this is not in the ordinary consciousness, but it is inevitably there. There is no possibility that dishonesty does not go deep into this person. One could imagine a devious scoundrel who has complete control over his facial expressions, what goes outwards, who has the most innocent face in the world, while unfolding the most villainous impulses; but in what is there in his astral body and gives him an inward expression, a facial expression, there he cannot be dishonest, there he makes himself a devil in the moment when he has his immoral motives. Outwardly, he can look as innocent as a child; inwardly, within himself, he looks like a devil; and the pure egoist looks at his heart with a devilish grin. This is just as much a law as the laws of nature are laws.

But now comes the crucial point. When an ugly physiognomy develops here (below), then the head, accustomed to the cosmos, rejects this physiognomy, does not take it in, and the human being forms in his etheric body such a body as was done with Ahriman, where the head has atrophied, has become instinctualized. Everything goes into the lower limbs of the etheric body. The head does not absorb this, and the human being makes himself Ahrimanic in his lower etheric body, and then also permeates his head with what this Ahrimanic body still pushes into the head. That is the strange thing, that in his head, already in the warmth ether of the head, the human being repels the physiognomy of the immoral, does not let it up. So that the immoral person carries an etheric Ahrimanic organism within him and his head remains unaffected by what is within him. It remains an image of the cosmos, but it actually belongs to him less and less because he cannot permeate it with his own being.

An immoral person gets little further than his life in the previous incarnation. Whatever has become his head in the transformation from the rest of the body of the previous incarnation remains the head, and when he dies, he has not come very far at all in relation to his head. On the other hand, what the moral imagination inwardly brings about flows up to the head in man. It causes the vertical direction. In fact, no immoral thing flows in the vertical direction. This gathers together and Ahrimanizes the human being. Only the moral flows in the vertical direction. And this is so because in the ether, in the warmth ether of the blood, the physiognomy of the immoral is rejected in the vertical direction. The head does not absorb this. The moral element, however, goes up into the head with the warmth of the blood, even more so in the light ether, and especially in the chemical and life ether. Man permeates his own being with his own being.

There is truly an influence of the moral into the physical, so that one can say: the etheric organization of the head has affinity for the moral in man, but not for the immoral. And no one can see how the moral impulses work into the physical through the detour via the ethereal, if they stop at mere physical-sensory observation of the world. One must take the human being as a whole, according to his etheric and astral organization, and then one has the field in which one sees how the moral element intervenes in the whole organization of the human being.

Now you can imagine what it looks like when a person dies. If his head has repelled the forces of his other organizations, then in fact nothing of him is actually in his head in the etheric body, which he sheds after a few days. He makes no particular impression on the world. He does not work with the further development of the earth, because he does not send any forces into that which reaches into the future. If a person has developed moral impulses within himself, which his head has taken up, then his ether body leaves him as a human being. The immoral person is abandoned by his ether body, in that the ether body really looks truly ahrimanic. One gets a good impression of the Ahrimanic form, even without making an effort to meet Ahriman himself, when one sees the etheric body of immoral people passing into the cosmos. It is Ahrimanized in form. In contrast, the etheric body that detaches from the astral body and the ego two or three days after the death of a person with moral impulses is humanized, humanly rounded and serene.

Such a person processes what he experiences as a human being on earth, including in his head, not just in the rest of his organism, and he hands it over to the cosmos through the similarity of his head. The head is indeed similar to the cosmos, the rest of the organism is not very similar to the cosmos; after some time, after it has been handed over to the cosmos, it is, one might say, scattered like a cloud and more or less falls to the earth, or at least is driven into currents that circle around the earth. But what a person has imprinted in his head in terms of morality is poured out into the vastness of the cosmos, and in this way the person contributes to the reshaping of the cosmos. And so we can say: By the way a person is moral or immoral, he contributes to the future of the earth. The immoral person hands over to the forces that surround the earth - and these are important for all activity, because the physical of the earth later arises out of the etheric - that which etherically trickles down to the earth and in turn connects with the earth, or what lives in the vicinity of the earth. The moral man, on the other hand, having absorbed into his head the forces that develop precisely through the moral impulses, gives to the whole cosmos what he has worked for on earth.

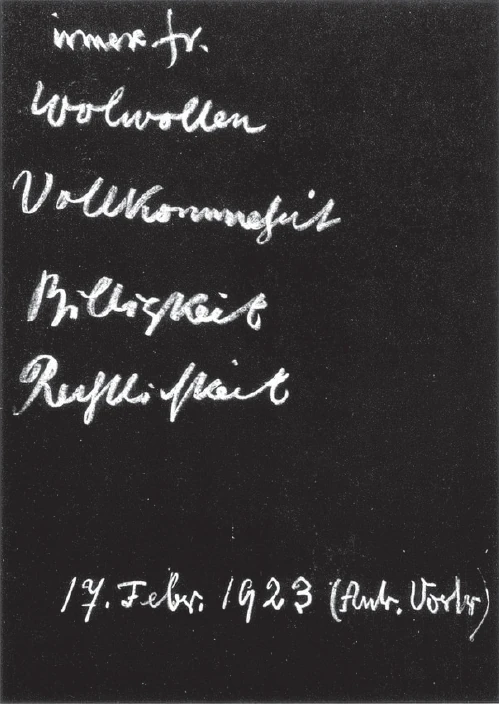

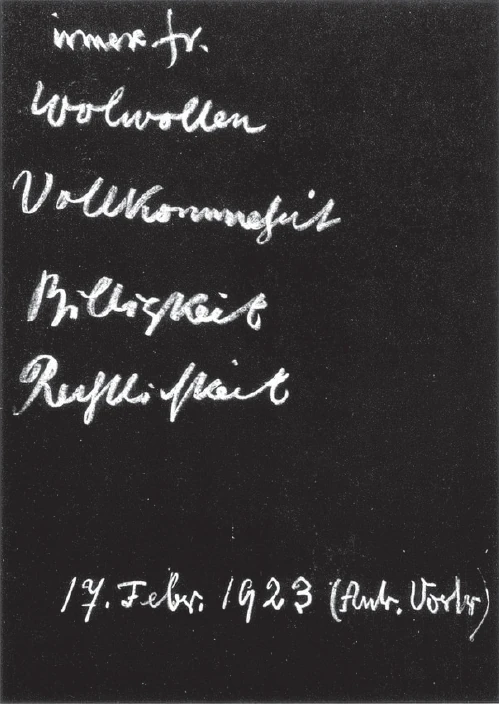

On Earth, if you remain attached to it, you cannot see how the moral impulses actually work; they remain abstractions. Take the moral impulses of any moral philosopher, say, for example, Ferbart. He lists five moral impulses: inner freedom, benevolence, perfection, equity and legality. So if a person acts according to these five types of virtue, he is a moral person. But Herbart cannot actually say what that is more than something abstract: he is just a moral person. But what that means for the world, that is not stated by such a philosopher.

Well, you can also name the virtues differently, depending on whether you summarize certain human impulses in one way or another. Yesterday I mentioned Nietzsche's four cardinal virtues, which in turn group somewhat differently. He distinguishes, as I said, honesty towards oneself and one's friends, bravery towards one's enemies, generosity towards the defeated, and courtesy towards all people. And other moral philosophers have listed other virtues. But all these virtues remain abstractions if one only knows the physical about a person. Then one stands before people with these virtues as impulses, as one stands before a machine with an order: No matter how well you address a machine, it does not occur to it to accept any of your impulses. Likewise, human nature, as expressed by today's world view, cannot accept any of the moral impulses. In order to understand the reality and effectiveness of the moral, one must enter the supersensible realm.

A supersensible thing is the inward-turned facial expression, the inward-turned gesture, which, depending on whether it is moral or immoral, is taken up or rejected by the head and thus passes into the world, or is shattered, burst, splintered on the earth.

Thus even a moral philosopher like Nietzsche, with his moral principles, is completely adrift and can only achieve a kind of consolidation, as I told you yesterday. But this is not a real consolidation. Despite everything, he ultimately had to resort to the human physical plane, despite all his “Beyond Good and Evil.” He failed because of this. Thus, if we wish to consider the efficacy of the moral, we must go beyond the mere physical world order, we must enter the supersensible realm, and we must be clear about the fact that although the moral appears abstractly in the physical, its efficacy can only be seen and judged in the supersensible.

VIII. Moralische Antriebe Und Physische Wirksamkeit Im Menschenwesen Das Erfassen Eines Geistesweges

Ich versuchte gestern an dem Beispiel Nietzsches, der Moralphilosoph sein wollte, auseinanderzusetzen, wie der Mensch, der ganz in der äuBeren heutigen Zivilisation lebt, und dennoch so wie eben Nietzsche Moralimpulse aus der vollen menschlichen Natur heraus suchen will, daran scheitern muß, daß aus der gegenwärtigen Erkenntnisart nicht gefunden werden kann, wie moralische Impulse in das physische Leben eingreifen. Wir haben ja heute eine Zivilisation, die auf der einen Seite naturwissenschaftliche Gesetze gelten läßt, welche auch unsere Erziehung schon so gestalten, daß wir von Kindheit auf Anschauungen über Zusammenhänge in der Natur aufnehmen. Wir haben andererseits eine moralische Weltanschauung, die für sich dasteht. Wir fassen die moralischen Impulse als Gebote oder als im Zusammenhange des sozialen Menschenlebens sich ergebende konventionelle Verhaltungsmaßregeln auf. Aber wir können das sittliche Leben auf der einen Seite und das physische Leben auf der anderen Seite nicht in einem innigen Zusammenhange denken. Und ich machte ja gestern darauf aufmerksam, wie Nietzsche aus dem heraus, was er zu seiner obersten Tugend machte, aus der Redlichkeit, aus der Ehrlichkeit gegen sich und andere, zuletzt doch dazu kam, am Menschen nur das Physische gelten zu lassen, und aus dem Physischen, das er als ein Menschliches-Allzumenschliches empfand, dann auch das Moralische hervorgehen zu lassen. Weil er ehrlich sein wollte gegenüber der Weltanschauung seiner Zeit, scheiterte er mit seiner Moralphilosophie daran, daß er nicht dazukommen konnte, zu sehen, wie Moralisches und Physisches in eins zusammenwirken.

Dieses Zusammenwirken kann man auch nicht sehen, wenn man nicht eintritt in jenes Gebiet, das man im richtigen Sinne das Übersinnliche nennt. Man muß sich darüber klar sein, daß nur im Menschenleben selber gewissermaßen der Kontakt hergestellt wird zwischen dem, was man als moralische Antriebe empfindet, zwischen den moralischen Idealen meinetwillen, und der physischen Wirksamkeit, den physischen Vorgängen im Menschenwesen selber. Und die große Frage ist heute diese: Wenn ich einen moralischen Impuls habe — bleibt er etwas ganz Abstraktes, oder kann er eingreifen in die physische Organisation?

Ich sagte Ihnen gestern: Wenn wir vor einer Maschine stehen, dann können wir sicher sein, in das Getriebe der Maschine greift ein moralischer Impuls nicht ein. Zwischen dem, was moralische Weltordnung ist und dem Mechanismus der Maschine, ist zunächst keine Verbindung. Wird nun, wie es immer mehr der Fall ist in der modernen naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung, der menschliche Organismus auch maschinenartig dargestellt, dann gilt das ja auch für den Menschen, dann bleiben die moralischen Impulse Illusionen. Der Mensch kann höchstens hoffen, daß irgendein Wesen, das ihm durch eine Offenbarung gegeben wird, in die moralische Weltordnung eingreift, die Guten belohnt und die Bösen bestraft; aber er kann nicht irgendwie aus der Weltordnung selbst heraus einen Zusammenhang zwischen den moralischen Impulsen und den physischen Vorgängen erschauen.

Nun möchte ich heute auf dasjenige Gebiet hinweisen, wo dieser Zusammenhang, zwischen dem, was der Mensch in sich als Moralisches erlebt und dem Physischen, wirklich auftritt. Um die Ausführungen, die ich zu machen haben werde, besser zu verstehen, nehmen wir zunächst das Tier.

Im Tier haben wir ein Zusammenwirken von dem physischen Organismus, einem ätherischen Bildekräfteorganismus und dem astralischen Organismus. Das eigentliche Ich ist ja nicht in der tierischen Organisation selber unmittelbar verkörpert, sondern greift von außen als ein Gruppen-Ich in die tierische Organisation ein. Nun müssen wir beim Tier uns klar darüber sein, daß in seiner Organisation zwei Richtungen deutlich zu unterscheiden sind. Wir sehen den tierischen Kopf. Auch bei den höheren Tieren ist, wie beim Menschen, der Kopf der vorzüglichste Träger des Nerven-Sinnesorganismus. Wir sehen, wie alles das, was das Tier von der äußeren Sinneswelt aufnimmt, durch die Organe seines Hauptes im wesentlichen in das Tier eindringt.

Gewiß, das gilt durchaus, was ich immer wieder betont habe, daß wir nicht auf einen physischen Teil eines Organismus die Gliederung des Organismus unmittelbar beziehen dürfen. Wir müssen sagen: Das Tier ist in einer gewissen Beziehung ganz Kopf, denn es kann überall längs seines Körpers wahrnehmen. Aber vorzugsweise ist das Tier eben Nerven-Sinnesorganismus am Kopfe. Da bewirkt es sein Verhältnis zu der äußeren Welt. Wenn wir dann das Tier in seiner Gesamtorganisation so betrachten, daß wir es in bezug auf seinen übrigen Organismus ansehen, wie es gewissermaßen den anderen Pol der Kopforganisation gegen das Schwanzende zu hat, so haben wir, wenn wir die Gliederung des Tieres in seiner physischen, ätherischen und astralischen Organisation betrachten, die Sache so, daß gewissermaßen von rückwärts nach vorne die astralische Beweglichkeit des Tieres fließt. Fortwährend gehen die astralischen Ströme, die Strömungen seines astralischen Organismus, von rückwärts nach vorne, und sie begegnen sich mit den Eindrücken, welche die Sinne am Kopfe erfahren. So daß wir ein Ineinanderströmen von rückwärts nach vorne und von vorne nach rückwärts im Tiere haben. Ich möchte schematisch dieses Ineinanderströmen so zeichnen, daß von rückwärts nach vorne die astralischen Strömungen beim Tiere gehen (rötliche Pfeile), daß ihnen entgegenströmen die Sinneseindrücke vom Haupt nach rückwärts (gelbliche Pfeile). Zwischen diesen beiden Strömungen ist beim Tiere ein über den ganzen Organismus ausgebreitetes Zusammenwirken.

Sie können am Hunde dieses Zusammenwirken deutlich sehen. Der Hund sieht seinen Herrn und wedelt. Wenn der Hund seinen Herrn sieht und wedelt, so bedeutet das, daß er den Eindruck von seinem Herrn hat, und daß diesem Eindruck, der von vorn nach rückwärts geht, also der Impression von außen das Astralische von innen entgegenströmt. Und dieses Entgegenströmen des ganzen Organismus von rückwärts nach vorne drückt sich im Wedeln des Hundes aus. Da ist ein völliges Zusarmmenstimmen. Und derjenige, der fragen wollte nach der Hundephysiognomie beim Ausdruck der Freude, der müßte eigentlich nicht so sehr das Gesicht des Hundes, wenn er seinen Herrn ins Auge faßt, anschauen, sondern er müßte das wedelnde Entgegenkommen des Schwanzes ins Auge fassen: da ist Physiognomie darinnen.

Das ist im Grunde genommen bei jedem Tiere so. Nur, sagen wir, wenn wir zu den Fischen heruntergehen, wird das nicht so bemerkt, weil da der astralische Leib eine große Selbständigkeit hat. Aber dem schauenden Bewußtsein ist es um so anschaulicher. Dem schauenden Bewußtsein wird ganz klar, daß, wenn der Fisch irgendwie durch seinen Nerven-Sinnesapparat etwas wahrnimmt, was ihm in der Strömung entgegenkommt, er selbst von rückwärts nach vorne seine eigene astralische Strömung dem entgegensendet, und dann ist ein wunderbares Ineinanderglitzern dessen, was der Fisch sieht, und dessen, was er entgegenbringt. Dieses innige Ineinandergreifen des astralischen Stromes von außen — denn es ist ein astralischer Strom von außen, den ein Wesen empfängt mit den Sinneseindrücken - und des astralischen Stromes von rückwärts nach vorne, das ist beim Menschen unterbrochen dadurch, daß der Mensch ein aufrechtes Wesen ist.

Dadurch, daß der Mensch ein aufrechtes Wesen ist, ist er nicht in der Lage, in derselben Weise wie etwa der Hund den astralischen Strom so unmittelbar den Sinneseindrücken entgegenzusenden. Der Hund hat ein horizontales Rückgrat. Die Bewegung des Astralischen von rückwärts nach vorne führt unmittelbar durch seinen Kopf durch. Beim Menschen ist der Kopf herausgehoben. Dadurch ist das ganze Verhältnis derjenigen astralischen Strömungen, die von rückwärts nach vorne strömen, die das eigentliche innere Wesen ausmachen, das Zusammenstimmen dieser Strömungen mit denjenigen Strömungen, die durch die Sinneseindrücke kommen, nicht so einfach, wie es beim Tiere ist. Und gerade, was die moralische Wesenheit des Menschen betrifft, so muß man das, was ich jetzt eben vorausgesetzt habe, genau studieren, um das Eingreifen des Moralischen in das Physische beim Menschen zu begreifen. Beim Tiere reden wir nicht von Moralität, weil eben beim Tiere dieses Strömen des Astralischen von rückwärts nach vorne und von vorne nach rückwärts durch nichts unterbrochen ist. Beim Menschen tritt das Folgende ein.

Es hebt ja der Mensch sein Haupt geradezu heraus aus der astralischen Strömung, die von ihm kommt, und die von rückwärts nach vorne geht. Dieses Herausheben des Hauptes bedeutet eben die Verkörperung des eigentlichen Ich. Daß das Blut gewissermaßen nicht bloß den horizontalen Weg macht, sondern daß das Blut hinaufströmen muß als Träger der inneren Ich-Kräfte, das macht, daß der Mensch dieses Ich als sein Ich, als sein individuelles Ich erlebt. Das macht aber auch, daß beim Menschen zunächst das Haupt, also der hauptsächlichste Träger der Sinneseindrücke, rein hingegeben ist der Außenwelt. Der Mensch ist eigentlich viel mehr so organisiert, daß er seinen Tastsinn in einer loseren Verbindung hat mit dem Gesichtssinn zum Beispiel als das Tier. Beim Tier ist ein inniger Kontakt des Tastsinnes und des Gesichtssinnes. Wenn das Tier etwas sieht, so hat es unmittelbar das Gefühl, daß es auch das, was es sieht, tastet. Die Tastorgane fühlen sich erregt auch durch das Sehen. Diese Erregung der Tastorgane, die kommt dann zusammen, namentlich mit dem Strom, der von rückwärts nach vorne geht. Beim Menschen ist das Haupt herausgehoben und rein hingegeben der äußeren Welt. Das drückt sich insbesondere beim Gesichtssinn aus. Der Gesichtssinn des Menschen ist, man möchte sagen, eine Art ätherischer Sinn. Wir lernen ja nur allmählich durch das Urteil abschätzen, was in der physischen Welt zum Beispiel Distanzen sind oder dergleichen. Wir sehen vorzugsweise als Menschen dasjenige, was im Farbigen und in den Abtönungen des Farbigen sich ausdrückt.

Bedenken Sie nur, daß der Mensch erst in derjenigen Zeit, in welcher der Intellektualismus geboren worden ist, auch zu der Perspektive im Malen übergegangen ist. Bei den älteren Malern finden Sie ja keine Raumperspektive, weil erst in dieser Zeit, auf dem Umwege durch das Urteil, durch den Intellektualismus, die Augen sich gewöhnt haben, dasjenige Wirkliche zu sehen, was sich in der Perspektive, also in Distanzierungen ausdrückt.

Für das Auge ist vorzugsweise Farbiges, Helldunkel, Abstufung des Helldunkels da. Das aber - indem es über die Gegenstände ausgebreitet ist — stammt ja eigentlich aus dem Weltenraum. Die Sonne sendet das Licht, und indem das Licht, das aus dem Weltenraume kommt, auf die Dinge der Erde fällt und zurückgeworfen wird, schaut das Auge eigentlich die Dinge nicht mit Hilfe der irdischen Kräfte, sondern mit Hilfe der kosmischen, der Weltenkräfte.

Das ist aber überhaupt symptomatisch für das menschliche Haupt. Es ist mehr hingegeben dem Ätherischen der Welt als dem Physischen. Der Mensch findet sich in die physische Welt eigentlich dadurch hinein, daß er in ihr herumgeht, daß er sie betastet. Aber er findet sich in die physische Welt weniger hinein durch das, was die Sinne seines Hauptes sind.

Denken Sie nur einmal, wie gespenstig die Welt wäre, wie ätherischgespenstig, wenn wir nicht durch den Tastsinn die Räumlichkeiten erfaßten, sondern wenn wir nur dasjenige von der Räumlichkeit erfaßten, was uns das Auge überliefert! Die tierische Organisation in bezug auf das Haupt ist eben durchaus anders als die menschliche Organisation. Die tierische Organisation hängt mit der physischen Wirklichkeit durch das Haupt viel mehr zusammen als die menschliche Organisation. Wenn der Mensch die Wahrnehmungen seines Hauptes nimmt, so hat er darin etwas Idealisches, weil Ätherisches. Er lebt eigentlich ganz in der Ätherwelt durch sein Haupt.

Nun ist ja auch das Haupt äußerlich — und das ist nicht etwas bloß Oberflächliches, was ich da erwähne -, sondern es ist auch das Haupt äußerlich beim Menschen nachgebildet dem Kosmos. Nehmen Sie die einzelnen tierischen Kopfgestaltungen. Sie sind unmittelbar ein Ausdruck der eigenen tierischen Körperlichkeit. Sie können jenes kosmisch Gerundete der Hauptesbildung beim Menschen nicht bei den Tieren finden. Der Mensch ist tatsächlich in seinem Haupte ein Abbild des Kosmisch-Sphärischen, und er ringt sich auf zu dieser Abbildlichkeit des Kosmisch-Sphärischen dadurch, daß er eben zu seiner Körperlinie nicht die Horizontale hat wie beim Tier, sondern die Vertikale; daß er sich heraushebt aus der Horizontalen in die Vertikale.

Das drückt sich aber insbesondere aus, wenn man die ganze Organisation des Menschen ins Auge faßt. Die physische Organisation des menschlichen Hauptes ist an eine ätherische Organisation gebunden, die wirklich ganz die Reinheit des Kosmos in sich spiegelt. Die Organisation des menschlichen Hauptes im ätherischen Leibe ist durch das ganze Erdenleben des Menschen hindurch etwas, was wenig berührt wird von dem Irdischen, was gerade in seinem Ätherischen und noch mehr in seinem Astralischen durchaus kosmisch bleibt. Es ist ja auch so, daß, wenn der Mensch von einem Erdenleben zu dem nächsten übergeht, die Organisation, die außerhalb seines Hauptes liegt, also das, was unterhalb seines Kopfes ist - der Kopf verliert sich ja als Kraftsystem nach dem Tode -, sich umwandelt, natürlich nicht die physische Materie, sondern der Kraftzusammenhang, sich metamorphosiert und zum Haupt in der nächsten Inkarnation, im nächsten Erdenleben wird. Es muß also die menschliche Organisation, um Hauptesorganisation zu werden, erst durch den Kosmos hindurchgehen. Auf Erden kann die menschliche Hauptesorganisation sich gar nicht ausbilden. Durch sein Haupt ist der Mensch durchaus hingegeben an das Kosmische, nur durch seine übrige Organisation ist der Mensch an das Irdische gebunden. Daher können wir sagen: Beim Tiere geht die ganze Konfiguration des Kopfes aus seiner übrigen Organisation hervor, beim Menschen hebt sich der Kopf mit einer gewissen Selbständigkeit aus der übrigen Organisation heraus. Diese übrige Organisation aber drängt sich in das Haupt des Menschen hinein in alledem, was im Menschen Geste und Mienenspiel des Gesichtes wird. Wenn Sie nämlich eine innere Erregung haben, sagen wir ein Angstgefühl, da drückt sich dasjenige, was innerhalb des Stoffwechselgebietes, im Blutzirkulationssystem liegt, durch die Kräfte des menschlichen Organismus im Blaßwerden des Gesichtes und im Mienenspiel aus. Und ähnlich ist es bei anderen inneren Erregungen. Wir sehen beim Menschen das, was in dem übrigen Organismus ist, sich geistig-seelisch, das heißt aber astralisch, in das Haupt hinein ergießen, und bis in die Färbung der Haut, aber namentlich bis in das Mienenspiel hinein, drückt sich physiognomisch, könnte man sagen, beweglich-physiognomisch im Haupte aus, was astralisch in dem übrigen Organismus lebt.

Man hat ein sehr interessantes Studium, wenn man zum Beispiel sieht, wie der Mensch das, was er spricht - das kommt ja aus seinem Ich -, mit einem gewissen Mienenspiel begleitet, wie sich in seinem Gesichte ausdrückt, was in seinem astralischen Leibe lebt. Sieht man einem Menschen, der spricht, ins Antlitz, dann empfängt man mit den Worten, die er ausspricht, sein Ich, und mit dem Mienenspiel die begleitenden Vorgänge in seinem astralischen Organismus. Aber mit diesem astfalischen Organismus des Hauptes, der das Mienenspiel ins Leben ruft, ist nun auch verbunden der ätherische Organismus des Hauptes, und dieser ätherische Organismus des Hauptes ist ein wunderbares Abbild des Kosmos. Es ist etwas sehr Merkwürdiges, wenn man durch übersinnliches Schauen einen sprechenden Menschen beobachtet. Da sieht man, wie in seinem Mienenspiel der astralische Organismus sich überall ankündigt, wie aber der ätherische Organismus des Hauptes wenig ergriffen wird von diesem Mienenspiel. Der ätherische Organismus des Hauptes sträubt sich, in sich, in seine Gestaltungen, das Mienenspiel aufzunehmen. Es ist sehr interessant, zu sehen, daß gewisse hymnische Gesänge zum Beispiel, in denen der Mensch vom Gefühl der Heiligkeit durchzogen ist in seinem astralischen Leibe, leicht in den ätherischen Leib des Hauptes hinein aufgenommen werden, und zwar zeigt der ätherische Leib gegen das Antlitz zu, bei jedem Mienenspiel ein Lichtspiel; aber in den weiter rückwärts gelegenen Partien zeigt der ätherische Leib einen scharfen Widerstand gegen das Aufnehmen irgendwelcher Vorgänge aus dem Mienenspiel.

Aus diesem ersehen Sie, daß das menschliche Haupt zwar in einer gewissen Beziehung zu dem übrigen Organismus steht, daß aber diese Beziehung gewissen Gesetzen unterliegt, weil der ätherische Leib nachgebildet ist dem Kosmos, und in dieser Konfiguration des Kosmos bleiben möchte, sich nicht beirren lassen möchte, namentlich nicht durch das, was aus den Leidenschaften, aus den Trieben, aus den Instinkten der menschlichen Natur kommt.

Nun gibt es etwas anderes höchst Bedeutsames. Im Antlitze schen wir ein gewisses Mienenspiel, das sich nach außen beim Menschen offenbart. Dieses Mienenspiel ist vom Temperament, vom Charakter des Menschen, von verschiedenen seelisch-physischen Eigentümlichkeiten abhängig. Aber es gibt ein anderes Mienenspiel im Menschen, sogar ein viel lebendigeres Mienenspiel, nur liegt dieses Mienenspiel nicht in seinem Bewußtsein, sondern es liegt im Unterbewußten. Es ist außersinnlicher Natur. Es liegt in einem Gebiet, wohin der Mensch mit seinem sinnlichen Beobachten nicht kommt. Wenn Sie nämlich den astralischen Leib des Menschen betrachten, nicht wie er dem Haupte angehört, sondern wie er namentlich dem Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus angehört, wenn Sie also den astralischen Leib des Menschen betrachten, wie er die Beine umschließt und durchdringt, wie er den Unterleib umschließt und durchdringt, dann bekommen Sie in diesem Teil des astralischen Organismus für übersinnliches Schauen auch ein Mienenspiel zu sehen, ein sehr lebendiges Mienenspiel, eine Physiognomie, die sich da ausdrückt. Und das Merkwürdige ist, daß dieses Mienenspiel, diese Physiognomie, von außen nach innen sich offenbart. Während also das Mienenspiel, welches das menschliche Sprechen oder sonst den menschlichen Anteil an der Umgebung äußert, sich nach außen offenbart, offenbart sich ein Mienenspiel, das der Mensch nicht in seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein hat, nach innen. Das ist eine sehr interessante Tatsache.

Ich möchte Ihnen das schematisch vor Augen führen. Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben hier den Menschen. Dann haben wir hier den astralischen Leib (rot), welcher der Veranlasser des Mienenspieles ist, der sich nach außen offenbart. Wir haben denselben astralischen Leib, aber einen anderen Teil davon hier (gelb), und während wir hier (oben) in diesem astralischen Leib das Mienenspiel sich nach außen offenbarend haben, haben wir hier (unten) ein Mienenspiel, das sich ganz nach innen offenbart: dieser Teil des astralischen Leibes wendet gewissermaßen ein Antlitz nach innen. Der Mensch weiß im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nichts davon, aber es ist so. Wenn wir das Kind betrachten, so finden wir, wie es fortwährend dieses Mienenspiel von diesem Teil des astralischen Leibes nach innen wendet, und wenn wir den mehr erwachsenen Menschen betrachten, so werden die Mienen sogar mehr oder weniger bleibend. Der Mensch bekommt da eine Physiognomie nach innen. Und was ist dieses Mienenspiel? Ja, diesem Mienenspiel liegt folgendes zugrunde.

Wenn der Mensch als Impuls hat, was man im gewöhnlichen Leben, aber mit Recht, eine gute Handlung, eine moralische Handlung nennt, dann ist ein anderes Mienenspiel nach innen vorhanden, als wenn man eine böse Handlung als Impuls in sich hat. Es ist gewissermaßen ein häßlicher Ausdruck, ein häßlicher Gesichtsausdruck, wenn ich so sagen darf, nach innen, wenn der Mensch eine egoistische Tat vollbringt. Denn es reduzieren sich im Grunde alle moralischen Taten auf das Unegoistische, alle unmoralischen Taten auf das Egoistische. Nur daß im gewöhnlichen Leben diese wirkliche moralische Beurteilung dadurch maskiert ist, daß jemand eigentlich sehr unmoralisch, nämlich durch und durch von egoistischen Motiven durchzogen sein kann, aber konventionell gewissen Moralregeln folgt. Das sind dann gar nicht seine eigenen. Da ist er eingefädelt in dasjenige, was ihm anerzogen ist, oder was er deshalb tut, weil er sich geniert vor dem, was die anderen sagen. Er ist eingefädelt als ein Glied in eine Kette. Aber das wirklich Moralische, das an der menschlichen Individualität eigentlich haftet, in ihr lebt, ist schon so beschaffen, daß das Gute von jenem Interesse kommt, das wiran dem anderen Menschen haben; von jenem Interesse, das wir dadurch gewinnen können, daß wir das, was andere fühlen und empfinden, als unser Eigenes fühlen und empfinden können, während das Unmoralische im Ursprünglichen etwas ist, wo der Mensch sich verschließt, wo er nicht mitempfindet, was andere Menschen empfinden. Gut denken heißt im Grunde genommen, sich in andere Menschen hineinversetzen können, böse denken heißt, sich in andere Menschen nicht hineinversetzen können. Das kann dann zu Gesetzen werden, zu konventionellen Regeln, zu Dingen, über die man sich geniert oder nicht geniert. Dann kann das, was eigentlich ein Egoistisches ist, sehr zurückgedrängt werden unter der Konvention. Aber es ist im Grunde genommen für die moralische Bewertung doch nicht dasjenige maßgebend, was der Mensch tut, sondern man muß tiefer in den menschlichen Charakter, in die menschliche Natur hineinschauen, um den eigentlichen moralischen Wert des Menschen beurteilen zu können.

Der moralische Wert drückt sich im astralischen Leibe dadurch aus, daß dieser Teil des astralischen Leibes ein schönes Antlitz nach innen wendet, wenn unegoistische Handlungen, altruistische Impulse im Menschen leben, und einen häßlichen Gesichtsausdruck nach innen wendet, wenn egoistische, böse Impulse im Menschen leben. So daß ein Geist, der in dem [astralischen] Menschen drinnen liest, genau ebenso nach dieser Physiognomie beurteilen kann, ob ein Mensch gut oder böse ist, wie man den Menschen nach anderen Eigenschaften an seinem Mienenspiel beurteilen kann. Das alles steht nicht im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, aber es ist unweigerlich da. Es gibt keine Möglichkeit, daß die Unehrlichkeit nicht tief in diesen Menschen hineingeht. Man könnte sich einen abgefeimten Schurken denken, der sein ganzes Gesichtsmienenspiel, das, was nach außen geht, in seiner Gewalt hätte, der das unschuldigste Gesicht von der Welt hätte, indem er die schurkischesten Impulse entfaltet; aber in dem, was da in seinem astralischen Leibe ist und ihm nach innen eine Physiognomie, eine Mimik gibt, da kann er nicht unredlich sein, da macht er sich in dem Momente zum Teufel, wo er eben seine unmoralischen Motive hat. Nach außen kann er unschuldig wie ein Kind schauen, nach innen hinein, in sich selber sieht er aus wie ein Teufel; und der reine Egoist schaut sein Herz mit teuflischem Grinsen an. Das ist einfach ebenso Gesetz, wie die Naturgesetze Gesetze sind.

Aber nun kommt dasjenige, was das Ausschlaggebende ist. Wenn hier eine häßliche Physiognomie sich entwickelt (unten), dann stößt der an den Kosmos gewöhnte Kopf diese Physiognomie zurück, nimmt sie nicht auf, und der Mensch bildet in seinem Ätherischen solch einen Leib aus, wie er beim Ahriman gemacht worden ist, wo das Haupt verkümmert ist, verinstinktiviert ist. Es geht alles in die unteren Glieder des ätherischen Leibes hinein. Das Haupt nimmt das nicht auf, und der Mensch macht sich ahrimanisch in seinem unteren ätherischen Leibe, und durchzieht dann auch sein Haupt mit dem, was dieser ahrimanische Leib noch in das Haupt hineinstößt. Das ist nämlich das Merkwürdige, daß der Mensch in seinem Haupt, schon in dem Wärmeäther des Hauptes, die Physiognomie des Unmoralischen abstößt, sie nicht hinaufläßt. So daß also der unmoralische Mensch einen ätherisch-ahrimanischen Organismus in sich trägt und sein Haupt unbeeinflußt bleibt von dem, was in ihm ist. Es bleibt zwar ein Abbild des Kosmos, aber es gehört ihm eigentlich immer weniger und weniger an, weil er es nicht mit seiner eigenen Wesenheit durchdringen kann.

Ein unmoralischer Mensch kommt dadurch wenig über sein Leben in der vorigen Inkarnation hinaus. Was sein Haupt geworden ist in der Umbildung aus dem übrigen Leib der vorigen Inkarnation, das bleibt das Haupt auch, und stirbt er, so ist er in bezug auf sein Haupt gar nicht sehr weit gekommen. Dagegen das, was die moralische Phantasie nach innen bewirkt, das strömt beim Menschen bis zum Haupte herauf. Es bewirkt die vertikale Richtung. In der vertikalen Richtung strömt nämlich eigentlich kein Unmoralisches. Dieses schoppt sich zusammen und ahrimanisiert den Menschen. In der vertikalen Richtung strömt nur das Moralische. Und zwar ist das so, daß schon in dem Äther, in dem Wärmeäther des Blutes in vertikaler Rich Tafel 3 tung die Physiognomie des Unmoralischen zurückgestoßen wird. Das Haupt nimmt das nicht auf. Das Moralische aber geht mit der Blutwärme schon im Wärmeäther in das Haupt hinauf, noch mehr im Lichtäther, und namentlich im chemischen und Lebensäther. Der Mensch durchdringt mit seinem eigenen Wesen sein Haupt.

Es ist wirklich ein Hineinwirken des Moralischen in das Physische, indem man sagen kann: die ätherische Hauptesorganisation des Menschen hat wohl Affinität zum Moralischen im Menschen, nicht aber zum Unmoralischen. Und niemand sieht ein, wie die moralischen Impulse ins Physische hineinwirken auf dem Umwege durch das Äthetische, der bei der bloßen physisch-sinnlichen Beobachtung der Welt stehen bleibt. Man muß den Gesamtmenschen nach ätherischer und astralischer Organisation nehmen, dann hat man das Gebiet, wo man sieht, wie das Moralische eingreift in die ganze Organisation des Menschen.

Nun können Sie sich denken, wie das anders aussieht, wenn der Mensch stirbt. Hat sein Haupt die Kräfte seiner übrigen Organisation zurückgestoßen, dann ist ja in dem Ätherleib, den er nach einigen Tagen abwirft, in seinem Haupte nichts von ihm eigentlich drinnen. Da macht er keinen besonderen Eindruck auf die Welt. Da arbeitet er nicht mit an der Fortentwickelung der Erde, weil er keine Kräfte hineinschickt in dasjenige, was in die Zukunft hineinreicht. Hat der Mensch moralische Impulse in sich entwickelt, die sein Haupt aufgenommen hat, dann verläßt ihn sein Ätherleib als ein Mensch. Der Unmoralische wird von seinem Ätherleib verlassen, indem der Ätherleib wirklich richtig ahrimanisch aussieht. Man bekommt einen guten Eindruck von der ahrimanischen Form, auch sogar ohne daß man sich bemüht, Ahriman selbst zu begegnen, wenn man den Ätherleib der unmoralischen Menschen in den Kosmos übergehen sieht. Der ist ahrimanisiert in seiner Form. Dagegen vermenschlicht, menschlich gerundet und abgeklärt ist der Ätherleib, der sich zwei, drei Tage nach dem Tode loslöst von dem astralischen Leib und dem Ich bei einem Menschen mit moralischen Impulsen.

Ein solcher Mensch verarbeitet dasjenige, was er als Mensch auf der Erde erlebt, auch in seinem Haupte, nicht bloß in seinem übrigen Organismus, und er übergibt es durch die Ähnlichkeit des Hauptes dem Kosmos. Das Haupt ist ja dem Kosmos ähnlich, der übrige Organismus ist nicht sehr ähnlich dem Kosmos; der wird nach einiger Zeit, nachdem er übergeben ist dem Kosmos, man möchte sagen, wie eine Wolke zerstreut und fällt auf die Erde mehr oder weniger nieder, oder wird wenigstens in Strömungen hineingetrieben, die um die Erde herumkreisen. Was der Mensch aber von seinem Moralischen in sein Haupt hineingeprägt hat, das wird in die Weiten des Kosmos ausgegossen, dadurch arbeitet der Mensch an einer Neugestaltung des Kosmos mit. Und so können wir sagen: An der Art und Weise, wie der Mensch moralisch oder unmoralisch ist, arbeitet er mit an der Zukunft der Erde. Der unmoralische Mensch übergibt den Kräften, welche die Erde umgeben - und die sind wichtig für alles Wirken, denn aus dem Ätherischen entsteht später das Physische der Erde -, dasjenige, was ätherisch auf die Erde niederrieselt und sich wiederum mit der Erde verbindet, oder was in dem Umkreise der Erde lebt. Der moralische Mensch dagegen, indem er in sein Haupt aufgenommen hat die Kräfte, die sich gerade durch die moralischen Impulse entwickeln, übergibt dem ganzen Kosmos das, was er auf der Erde erarbeitet hat.

Auf der Erde kann man, wenn man an ihr haften bleibt, nicht sehen, wie die moralischen Impulse eigentlich wirken; da bleiben sie Abstraktionen. Nehmen Sie bei irgendeinem Moralphilosophen, sagen wir zum Beispiel Ferbart, die moralischen Impulse. Er führt fünf moralische Impulse an: die innere Freiheit, das Wohlwollen, die Vollkommenheit, die Billigkeit und die Rechtlichkeit. Wenn also ein Mensch nach diesen fünf Tugendarten sich richtet, ist er ein moralischer Mensch. Aber Herbart kann eigentlich nicht angeben, was das mehr ist als etwas Abstraktes: er ist halt ein moralischer Mensch. Aber was das für die Welt bedeutet, das gibt solch ein Philosoph nicht an.

Nun ja, man kann ja auch die Tugenden anders benennen, je nachdem man gewisse menschliche Impulse so oder so zusammenfaßt. Ich habe Ihnen gestern die vier Kardinaltugenden Nietzsches angeführt, der wiederum etwas anders gruppiert. Er unterscheidet, wie ich gesagt habe, Redlichkeit gegen sich und seine Freunde, Tapferkeit gegen seine Feinde, Großmut gegen die Besiegten und Höflichkeit gegen alle Menschen. Und andere Moralphilosophen haben wiederum andere Tugenden angeführt. Aber alle diese Tugenden bleiben Abstraktionen, wenn man vom Menschen nur das Physische weiß. Dann steht man mit diesen Tugenden als Impulsen vor den Menschen, wie man mit einem Befehl vor der Maschine steht: Sie können einer Maschine noch so gut zureden, es fällt ihr gar nicht ein, etwas von Ihren Impulsen anzunehmen. Ebenso kann die Menschennatur, von der die heutige Weltanschauung spricht, nichts annehmen von den moralischen Impulsen. Man muß, um die Wirklichkeit, die Wirksamkeit des Moralischen einzusehen, eben das Gebiet des Übersinnlichen betreten.

Ein Übersinnliches ist die nach innen gewendete Mimik, die nach innen gewendete Gebärde, die, je nachdem sie moralisch oder unmoralisch ist, vom Haupte aufgenommen oder zurückgestoßen wird und dadurch in die Welt übergeht, oder auf der Erde zerschellt, zerberstet, zersplittert wird.

So hängt selbst ein Moralphilosoph von jener inneren Kraft wie Nietzsche vollständig in der Luft mit seinen Moralprinzipien und kann nur auf die Art zu einer Festigung kommen, wie ich es Ihnen gestern erzählt habe. Aber das ist keine wirkliche Festigung. Er mußte trotz allem « Jenseits von Gut und Böse» zuletzt auf die menschliche Physis zurückgehen. Daran scheiterte er. So muß man, wenn man die Wirksamkeit des Moralischen ins Auge fassen will, über die bloße physische Weltordnung hinausgehen, muß das Gebiet des Übersinnlichen betreten, muß sich klar sein darüber, daß das Moralische zwar abstrakt hereinscheint in das Physische, daß aber seine Wirksamkeit nur im Übersinnlichen geschaut und beurteilt werden kann.