Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age

GA 7

Valentin Weigel and Jacob Boehme

[ 1 ] Paracelsus was primarily concerned with developing ideas about nature that breathe the spirit of the higher cognition he advocated. A kindred thinker who applied the same way of thinking to man's own nature in particular is Valentin Weigel (1533–1588). He grew out of Protestant theology as Eckhart, Tauler, and Suso grew out of Catholic theology. He had precursors in Sebastian Frank and Caspar Schwenckfeldt. They emphasized the deepening of the inner life, in contrast to the church dogma with its attachment to an external creed. For them it is not the Jesus whom the Gospels preach who is of value, but the Christ who can be born in every man out of his deeper nature, and who is to be his deliverer from the lower life and his leader in the ascent to the ideal. Weigel quietly and modestly administered his incumbency in Zschopau. It is only from his posthumous writings printed in the seventeenth century that one discovers something about the significant ideas he had developed concerning the nature of man. (Of his writings we shall mention here: Der güldene Griff, Alle Ding ohne Irrthumb zu erkennen, vielen Hochgelährten unbekannt, und doch allen Menschen nothwendig zu wissen, The Golden art of Knowing Everything without Error, unknown to Many of the Learned, and yet Necessary for all Men to Know.—Erkenne dich selber, Know Thyself.—Vom Ort der Welt, Of the Place of the World.) Weigel is anxious to come to a clear idea of his relationship to the teachings of the Church. This leads him to investigate the foundations of all cognition. Man can only decide whether he can know something through a creed if he understands how he knows. Weigel takes his departure from the lowest kind of cognition. He asks himself, How do I apprehend a sensory thing when it confronts me? From there he hopes to be able to ascend to the point where he can give an account of the highest cognition.—In sensory apprehension the instrument (sense organ) and the thing, the “counterpart,” confront each other. “Since in natural perception there must be two things, namely the object or counterpart, which is to be perceived and seen by the eye, and the eye, or the perceiver, which sees and perceives the object, therefore, consider the question, Does the perception come from the object into the eye, or does the judgment, and the perception, flow from the eye into the object.” (Der güldene Griff, chap. 9) Now Weigel says to himself, If the perception flowed from the counterpart (thing) into the eye, then, of one and the same thing, the same complete perception would of necessity have to arise in all eyes. But this is not the case; rather, everyone sees according to his eyes. Only the eyes, not the counterpart, can be responsible for the fact that many different conceptions of one and the same thing are possible. In order to make the matter clear, Weigel compares seeing with reading. If the book did not exist of course I could not read it; but it could be there, and I would still not be able to read anything in it if I did not know the art of reading. Thus the book must be there, but of itself it cannot give me anything at all; everything that I read I must bring forth out of myself. That is also the nature of natural (sensory) perception. Color exists as a “counterpart;” but out of itself it cannot give the eye anything. On its own, the eye must perceive what color is. The color is no more in the eye than the content of the book is in the reader. If the content of the book were in the reader, he would not have to read it. Nevertheless, in reading, this content does not flow out of the book, but out of the reader. It is the same with the sensory object. What this sensory object is outside, does not flow into man from the outside, but rather from the inside.—On the basis of these ideas one could say, If all perception flows from man into the object, then one does not perceive what is in the object, but only what is in man himself. A detailed elaboration of this train of thought is presented in the views of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). (I have shown the erroneous aspect of this train of thought in my book,Die Philosophie der Freiheit, Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. Here I must confine myself to saying that with this simple, straightforward way of thinking Valentin Weigel stands on a much higher level than Kant.)—Weigel says to himself, Although perception flows from man yet it is only the nature of the counterpart which emerges from the latter by way of man. As it is the content of the book which I discover by reading and not my own, so it is the color of the counterpart which I discover through the eye, not the color which is in the eye, or in me. On his own path Weigel thus comes to a conclusion which we have already encountered in the thinking of Nicolas of Cusa. In his way Weigel has elucidated the nature of sensory perception for himself. He has attained the conviction that everything external things have to tell us can only flow out from within ourselves. Man cannot remain passive if he wants to perceive the things of the senses, and be content with letting them act upon him; he must be active, and bring this perception out of himself. The counterpart alone awakens the perception in the spirit. Man ascends to higher cognition when the spirit becomes its own object. In considering sensory perception, one can see that no cognition can flow into man from the outside. Therefore the higher cognition cannot come from the outside, but can only be awakened within man. Hence there can be no external revelation, but only an inner awakening. And as the external counterpart waits until man confronts it, in whom it can express its nature, so must man wait, when he wants to be his own counterpart, until the cognition of his nature is awakened in him. While in the sensory perception man must be active in order to present the counterpart with its nature, in the higher cognition he must remain passive, because now he is the counterpart. He must receive his nature within himself. Because of this the cognition of the spirit appears to him as an illumination from on high. In contrast with the sensory perception, Weigel therefore calls the higher cognition the “light of grace.” This “light of grace” is in reality nothing but the self-cognition of the spirit in man, or the rebirth of knowledge on the higher level of seeing.—As Nicolas of Cusa, in pursuing his road from knowing to seeing, does not really let the knowledge acquired by him be reborn on a higher level, but is deceived into regarding the church creed, in which he had been educated, as this rebirth, so is this the case with Weigel too. He finds his way to the right road, and loses it again at the moment he enters upon it. One who wants to walk the road which Weigel indicates can regard the latter as a leader only up to its starting-point.

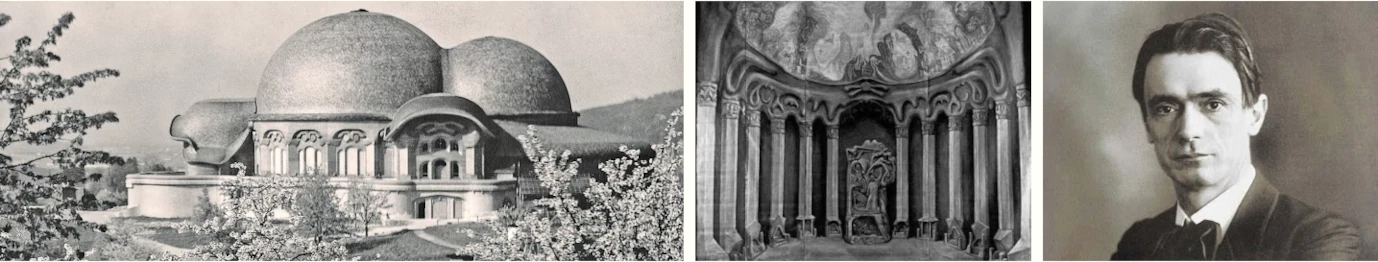

[ 2 ] What we encounter in the works of the master shoemaker of Görlitz, Jacob Boehme (1575–1624), is like the jubilation of nature, which, at the peak of its development, admires its essence. Before us appears a man whose words have wings, woven out of the blissful feeling that he sees the knowledge in himself shining as higher wisdom. Jacob Boehme describes his condition as a devotion which only desires to be wisdom, and as a wisdom which desires to live in devotion alone: “When I wrestled and fought, with God's assistance, there arose a wondrous light in my soul which was altogether foreign to wild nature, and by which I first understood what God and man are, and what God has to do with man.” Jacob Boehme no longer feels himself to be a separate personality which utters its insights; he feels himself to be an organ of the great universal spirit which speaks in him. The limits of his personality do not appear to him as limits of the spirit which speaks out of him. For him this spirit is omnipresent. He knows that “the sophist will censure him” when he speaks of the beginning of the world and of its creation, “since I was not there and did not see it myself. Let him be told that in the essence of my soul and body, when I was not yet the I, but Adam's essence, I was indeed there, and that I myself have forfeited my felicity in Adam.” It is only in external similes that Boehme can intimate how the light broke forth within himself. When as a boy he once is on the summit of a mountain, above where great red stones seem to close the mountain off, he sees an open entrance, and in its depths a vessel containing gold. He is overcome with awe, and goes his way without touching the treasure. Later he is serving his apprenticeship with a shoemaker in Görlitz. A stranger walks into the store and asks for a pair of shoes. Boehme is not allowed to sell them to him in the master's absence. The stranger leaves, but after a while calls the apprentice outside and says to him, Jacob, you are little, but one day you will become an altogether different man, at whom the world will be filled with astonishment. At a more mature period of his life Jacob Boehme sees the sunshine reflected in a burnished pewter vessel; the sight which confronts him seems to him to reveal a profound mystery. From the time he experiences this manifestation he believes himself to be in possession of the key to the mysterious language of nature.—He lives as a spiritual hermit, supporting himself modestly by his trade, and at the same time setting down, as if for his own memory, the notes which sound in him when he feels the spirit within himself. The zealotry of priestly fanaticism makes his life difficult. He wants to read only that scripture which the light within himself illuminates for him, but is pursued and tormented by those to whom only the external scripture, the rigid, dogmatic creed, is accessible.

[ 3 ] Jacob Boehme is filled with a restlessness which impels him toward cognition, because a universal mystery lives in his soul. He feels himself to be immersed in a divine harmony with his spirit, but when he looks around him he sees disharmony everywhere in the divine works. To man belongs the light of wisdom, yet he is exposed to error; there lives in him the impulse toward the good, and yet the dissonance of evil can be heard throughout the course of human development. Nature is governed by great natural laws, and yet its harmony is disturbed by superfluities and by the wild struggle of the elements. How is the disharmony in the harmonious, universal whole to be understood? This question torments Jacob Boehme. It comes to occupy the center of his world of ideas. He wants to attain a conception of the universal whole which includes the inharmonious too. For how can a conception explain the world which leaves the existing inharmonious elements aside, unexplained? Disharmony must be explained through harmony, evil through good itself. In speaking of these things, let us limit ourselves to good and evil; in the latter, disharmony in the narrower sense finds its expression in human life. For this is what Jacob Boehme basically limits himself to. He can do this, for to him nature and man appear as one essence. He sees similar laws and processes in both. The non-functional is for him an evil in nature, just as the evil is for him something non-functional in human destiny. Here and there it is the same basic forces which are at work. To one who has understood the origin of evil in man, the origin of evil in nature is also plain.—How is it possible for evil as well as for good to flow out of the same primordial essence? If one speaks in the spirit of Jacob Boehme, one gives the following answer: The primordial essence does not exist in itself alone. The diversity of the world participates in this existence. As the human body does not live its life as a single part, but as a multiplicity of parts, so too does the primordial essence. And as human life is poured into this multiplicity of parts, so is the primordial essence poured into the diversity of the things of this world. Just as it is true that the whole man has one life, so is it true that each part has its own life. And it no more contradicts the whole harmonious life of man that his hand should turn against his own body and wound it, than it is impossible that the things of the world, which live the life of the primordial essence in their own way, should turn against one another. Thus the primordial life, in distributing itself over different lives, bestows upon each life the capacity of turning itself against the whole. It is not out of the good that the evil flows, but out of the manner in which the good lives. As the light can only shine when it penetrates the darkness, so the good can only come to life when it permeates its opposite. Out of the “abyss” of darkness shines the light; out of the “abyss” of the indifferent, the good brings itself forth. And as in the shadow it is only brightness which requires a reference to light, while the darkness is felt to be self-evident, as something that weakens the light, so too in the world it is only the lawfulness in all things which is sought, and the evil, the non-functional, which is accepted as the self-evident. Hence, although for Jacob Boehme the primordial essence is the All, nothing in the world can be understood unless one keeps in sight both the primordial essence and its opposite. “The good has swallowed the evil or the repugnant into itself ... Every being has good and evil within itself; and in its development, having to decide between them, it becomes an opposition of qualities, since one of them seeks to overcome the other.” It is therefore entirely in the spirit of Jacob Boehme to see both good and evil in every object and process of the world; but it is not in his spirit to seek the primordial essence without further ado in the mixture of the good with the evil. The primordial essence had to swallow the evil, but the evil is not a part of the primordial essence. Jacob Boehme seeks the primordial foundation of the world, but the world itself arose out of the abyss by means of the primordial foundation. “The external world is not God, and in eternity is not to be called God, but is only a being in which God reveals Himself ... When one says, God is everything, God is heaven and earth and also the external world, then this is true; for everything has its origin from Him and in Him. But what am I to do with such a saying that is not a religion?”—With this conception as a background, his ideas about the nature of the world developed in Jacob Boehme's spirit in such a way that he lets the lawful world arise out of the abyss in a succession of stages. This world is built up in seven natural forms. The primordial essence receives a form in dark acerbity, silently enclosed within itself and motionless. It is under the symbol of salt that Boehme conceives this acerbity. With such designations he leans upon Paracelsus, who has borrowed the names for the process of nature from the chemical processes (>cf. above). By swallowing its opposite, the first natural form takes on the shape of the second; the harsh and motionless takes on motion; energy and life enter into it. Mercury is the symbol for this second form. In the struggle of stillness with motion, of death with life, the third natural form (sulphur) appears. This life, with its internal struggle, is revealed to itself; henceforth it does not live in an external struggle of its parts; like a uniformly shining lightning, illuminating itself, it thrills through its own being (fire). This fourth natural form ascends to the fifth, the living struggle of the parts reposing within itself (water). On this level exists an inner acerbity and silence as on the first, only it is not an absolute quiet, a silence of the inner contrasts, but an inner movement of the contrasts. It is not the quiet which reposes within itself, but which has motion, which was kindled by the fiery lightning of the fourth stage. On the sixth level, the primordial essence itself becomes aware of itself as such an inner life; it perceives itself through sense organs. It is the living organisms, endowed with senses, which represent this natural form. Jacob Boehme calls it sound or resonance, and thus sets up the sensory impression of hearing as a symbol for sensory perception in general. The seventh natural form is the spirit elevating itself by virtue of its sensory perceptions (wisdom). It finds itself again as itself, as the primordial foundation, within the world which has grown out of the abyss and shaped itself out of harmonious and inharmonious elements. “The Holy Ghost brings the splendor of majesty into the entity in which the Divinity stands revealed.”—With such conceptions Jacob Boehme seeks to fathom that world which, in accordance with the knowledge of his time, appears to him as the real one. For him facts are what the natural science of his time and the Bible regard as such. His way of thinking is one thing, his world of facts another. One can imagine the former as applied to a quite different factual knowledge. And thus there appears before our mind a Jacob Boehme who could also be living at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century. Such a man would not penetrate with his thinking the biblical story of the Creation and the struggle of the angels with the devils, but rather Lyell's geological insights and the “natural history of creation” of Haeckel. One who penetrates to the spirit of Jacob Boehme's writings must come to this conviction.1This sentence must not be understood as meaning that the investigation of the Bible and of the spiritual world would be an aberration at the present time; what is meant is that a “Jacob Boehme of the nineteenth century” would be led by paths similar to those which led the one of the sixteenth century to the Bible, to the “natural history of creation.” But from there he would press forward to the spiritual world. (We shall mention the most important of these writings: Die Morgenröthe im Aufgang, The Coming of the Dawn. Die drei Prinzipien göttlichen Wesens, The Three Principles of the Divine Essence. Vom dreifachen Leben des Menschen, Of the Threefold Life of Man. Das umgewandte Auge, The Eye Turned Upon Itself. Signatura rerum oder von der Geburt und Bezeichnung aller Wesen, Signatura rerum or of the birth and designation of all beings. Mysterium magnum.)

V. Valentin Weigel und Jacob Böhme

[ 1 ] Paracelsus kam es vor allen Dingen darauf an, über die Natur Ideen zu gewinnen, die den Geist der von ihm vertretenen höheren Erkenntnis atmen. Ein ihm verwandter Denker, der die gleiche Vorstellungsart vorzugsweise auf die eigene Natur des Menschen anwandte, ist Valentin Weigel (1533-1588). Er ist in ähnlichem Sinne aus der protestantischen Theologie herausgewachsen wie Eckhart, Tauler und Suso aus der katholischen. Er hat Vorgänger in Sebastian Frank und Caspar Schwenckfeldt. Diese deuteten gegenüber dem am äußerlichen Bekenntnis hängenden Kirchenglauben, auf die Vertiefung des inneren Lebens. Ihnen ist nicht der Jesus wertvoll, den das Evangelium predigt, sondern der Christus, der in jedem Menschen aus dessen tieferer Natur geboren werden kann, und der ihm Erlöser vom niederen Leben und Führer zu idealer Erhebung sein soll. Weigel verwaltete still und bescheiden sein Pfarramt in Zschopau. Erst aus seinen hinterlassenen, im siebzehnten Jahrhundert gedruckten Schriften erfuhr man etwas von den bedeutsamen Ideen, die ihm über die Natur des Menschen aufgegangen waren. (Von seinen Schriften seien genannt: «Der güldene Griff; das ist: All Ding ohne Irrthumb zu erkennen, vielen Hochgelährten unbekannt, und doch allen Menschen nothwendig zu wissen.» «Erkenne dich selber.» - «Vom Ort der Welt.») Es drängt Weigel, sich über sein Verhältnis zur Lehre der Kirche klar zu werden. Das führt ihn dazu, die Grundfesten aller Erkenntnis zu untersuchen. Ob der Mensch etwas durch ein Glaubensbekenntnis erkennen könne, darüber kann er sich nur Rechenschaft geben, wenn er weiß, wie er erkennt. Von der untersten Art des Erkennens geht Weigel aus. Er fragt sich: wie erkenne ich ein sinnliches Ding, wenn es nur entgegentritt? Von da hofft er aufsteigen zu können bis zu dem Gesichtspunkte, wo er sich über die höchste Erkenntnis Rechenschaft geben kann. - Bei der sinnlichen Erkenntnis stehen sich das Werkzeug (Sinnesorgan) und das Ding, der «Gegenwurf» gegenüber. «Dieweil in der natürlichen Erkenntnis sein müssen zwei Dinge, als das Objekt oder Gegenwurf, der soll erkannt und gesehen werden vom Auge; und das Auge, oder der Erkenner, der das Objekt sieht, und erkennt, so halte gegeneinander: ob die Erkenntnis herkomme vom Objekt in das Auge; oder ob das Urteil, und die Erkenntnis fließe vom Auge in das Objekt.» («Der güldene Griff», 9. Kap.) Nun sagt sich Weigel: Würde die Erkenntnis aus dem Gegenwurf (Ding) in das Auge fließen, so müßte notwendig von einem und demselben Ding eine gleiche und vollkommene Erkenntnis in alle Augen kommen. Dies ist aber nicht der Fall, sondern jeder sieht nach Maßgabe seiner Augen. Nur die Augen, nicht der Gegenwurf, können schuld daran sein, daß von einem und demselben Ding vielerlei verschiedene Vorstellungen möglich sind. Weigel vergleicht, zur Klärung der Sache, das Sehen mit dem Lesen. Wäre das Buch nicht, so könnte ich es natürlich nicht lesen; aber es könnte immerhin da sein, und dennoch könnte ich nichts darin lesen, wenn ich nicht die Kunst, zu lesen, verstände. Das Buch muß also da sein; aber es kann mir, von sich aus, nicht das geringste geben; ich muß alles, was ich lese, aus mir herausholen. Das ist auch das Wesen der natürlichen (sinnlichen) Erkenntnis. Die Farbe ist als «Gegenwurf» da; aber sie kann, von sich aus, nichts dem Auge geben. Das Auge muß von sich aus erkennen, was die Farbe ist. So wenig wie der Inhalt des Buches in dem Leser ist, so wenig ist die Farbe im Auge. Wäre der Inhalt des Buches in dem Leser: er brauchte es nicht zu lesen. Dennoch fließt im Lesen dieser Inhalt nicht aus dem Buche, sondern aus dem Leser. So ist es auch mit dem sinnlichen Ding. Was dieses sinnliche Ding draußen ist, das fließet nicht von außen herein in den Menschen, sondern von innen heraus. - Man könnte, von diesen Gedanken ausgehend, sagen: Wenn alle Erkenntnis aus dem Menschen in den Gegenstand fließt, so erkennt man nicht, was im Gegenstande ist, sondern nur, was im Menschen selbst ist. Die ausführliche Durchbildung dieses Gedankenganges hat die Anschauung Immanuel Kants (1724-1804) gebracht. (Das Irrige dieses Gedankenganges findet man in meinem Buch «Philosophie der Freiheit» dargestellt. Hier muß ich mich darauf beschränken, zu erwähnen, daß Valentin Weigel mit seiner einfachen, urwüchsigen Vorstellungsart viel höher steht als Kant.) - Weigel sagt sich: Wenn auch die Erkenntnis aus dem Menschen fließt, so ist es doch nur das Wesen des Gegenwurfes, das von diesem auf dem Umwege durch den Menschen zum Vorschein kommt. Wie ich den Inhalt des Buches durch das Lesen erfahre, und nicht meinen eigenen, so erfahre ich die Farbe des Gegenwurfes durch das Auge; nicht die im Auge, oder in mir befindliche Farbe. Auf einem eigenen Wege kommt also Weigel zu einem Ergebnis, das uns bereits bei Nicolaus von Kues entgegengetreten ist. So hat sich Weigel über das Wesen der sinnlichen Erkenntnis aufgeklärt. Er ist zu der Ãœberzeugung gekommen, daß alles, was uns die äußeren Dinge zu sagen haben, nur aus unserem eigenen Innern selbst herausfließen kann. Der Mensch kann sich nicht leidend verhalten, wenn er die sinnlichen Dinge erkennen will, und diese bloß auf sich wirken lassen wollen; sondern er muß sich tätig verhalten, und die Erkenntnis aus sich herausholen. Der Gegenwurf erweckt nur in dem Geiste die Erkenntnis. Zur höheren Erkenntnis steigt der Mensch auf, wenn der Geist sein eigener Gegenwurf wird. An der sinnlichen Erkenntnis ersieht man, daß keine Erkenntnis von außen in den Menschen einfließen kann. Also kann auch die höhere Erkenntnis nicht von außen kommen, sondern nur im Innern erweckt werden. Es kann daher keine äußere Offenbarung, sondern nur eine innere Erweckung geben. So wie nun der äußere Gegenwurf wartet, bis der Mensch ihm entgegentritt, in dem er sein Wesen aussprechen kann, so muß der Mensch, wenn er sich selbst Gegenwurf sein will, warten, bis in ihm die Erkenntnis seines Wesens erweckt wird. Muß in der sinnlichen Erkenntnis sich der Mensch tätig verhalten, damit er dem Gegenwurf dessen Wesen entgegenbringen kann, so muß in der höheren Erkenntnis sich der Mensch leidend verhalten, weil er jetzt Gegenwurf ist. Er muß sein Wesen in sich empfangen. Deshalb erscheint ihm die Erkenntnis des Geistes als Erleuchtung von oben. Im Gegensatz zur sinnlichen Erkenntnis nennt daher Weigel die höhere Erkenntnis das «Licht der Gnaden». Dieses «Licht der Gnaden» ist in Wirklichkeit nichts anderes als die Selbsterkenntnis des Geistes im Menschen, oder die Wiedergeburt des Wissens auf der höheren Stufe des Schauens. - Wie nun Nicolaus von Kues beim Verfolgen seines Weges vom Wissen zum Schauen nicht wirklich das von ihm gewonnene Wissen auf höherer Stufe wiedergeboren werden läßt, sondern wie sich ihm das kirchliche Bekenntnis, in dem er erzogen ist, als solche Wiedergeburt vortäuscht, so ist das auch bei Weigel der Fall. Er führt sich auf den rechten Weg und verliert diesen in dem Augenblick wieder, in dem er ihn betritt. Wer den Weg gehen will, den Weigel weist, der kann diesen selbst nur bis zum Ausgangspunkte als Führer betrachten.

[ 2 ] Es ist wie das Aufjauchzen der Natur, die, auf dem Gipfel ihres Werdens, ihre Wesenheit bewundert, was uns aus den Werken des Görlitzer Schuhmachermeisters Jacob Böhme (1575-1624) entgegentönt. Ein Mann erscheint vor uns, dessen Worte Flügel haben, gewoben aus der beseligenden Empfindung, das Wissen in sich als höhere Weisheit leuchten zu sehen. Als eine Frömmigkeit, die nur Weisheit sein will, und als eine Weisheit, die allein in Frömmigkeit leben will, beschreibt Jacob Böhme seinen Zustand: «Als ich in Gottes Beistand rang und kämpfte, da ging meiner Seele ein wunderliches Licht auf, das der wilden Natur ganz fremd war, darin ich erst erkannte, was Gott und Mensch wäre, und was Gott mit den Menschen zu tun hätte.» Jacob Böhme fühlt sich nicht mehr als einzelne Persönlichkeit, die ihre Erkenntnisse ausspricht; er fühlt sich als Organ des großen Allgeistes, der in ihm spricht. Die Grenzen seiner Persönlichkeit erscheinen ihm nicht als Grenzen des Geistes, der aus ihm redet. Dieser Geist ist ihm allgegenwärtig. Er weiß, daß «der Sophist ihn tadeln» werde, wenn er vom Anfang der Welt und ihrer Schöpfung spricht, «dieweil ich nicht sei dabei gewesen und es selber gesehn. Dem sei gesagt, daß in meiner Seelen- und Leibesessenz, da ich noch nicht der Ich war, sondern da ich Adams Essenz war, bin ja dabei gewesen und meine Herrlichkeit in Adam selber verscherzet habe.» Nur in äußeren Gleichnissen vermag Böhme anzudeuten, wie in seinem Innern das Licht hervorgebrochen. Als er sich einmal als Knabe auf dem Gipfel eines Berges befindet, da sieht er oben, wo große rote Steine den Berg zu schließen scheinen, den Eingang offen und in seiner Vertiefung ein Gefäß mit Gold. Ein Schauer überfällt ihn; und er geht seiner Wege, ohne den Schatz zu berühren. Später ist er in Görlitz bei einem Schuhmacher in der Lehre. Ein fremder Mann tritt in den Laden und verlangt ein Paar Schuhe. Böhme darf sie ihm in Abwesenheit des Meisters nicht verkaufen. Der Fremde entfernt sich, ruft aber nach einer Weile den Lehrling heraus, und sagt ihm: Jacob, du bist klein, aber du wirst einst ein ganz anderer Mensch werden, über den die Welt in Erstaunen ausbrechen wird. In reiferen Jahren sieht Jacob Böhme beim Glanz der Sonne die Spiegelung eines zinnernen Gefäßes: der Anblick, der sich ihm da bietet, scheint ihm ein tiefes Geheimnis zu entschleiern. Er glaubt sich seit dem Eindrucke dieser Erscheinung im Besitze des Schlüssels zu der Rätselsprache der Natur. - Als geistiger Einsiedler lebt er, bescheiden sich von seinem Handwerk ernährend, und daneben, wie für sein eigenes Gedächtnis, die Töne aufzeichnend, die in seinem Innern klingen, wenn er den Geist in sich fühlt. Zelotischer Priestereifer macht dem Manne das Leben schwer. Er, der nur die Schrift lesen will, die ihm das Licht seines Innern erleuchtet, wird verfolgt und gequält von denen, welchen nur die äußere Schrift, das starre, dogmatische Bekenntnis zugänglich ist.

[ 3 ] Ein Welträtsel lebt als Unruhe, die zur Erkenntnis treibt, in Jacob Böhmes Seele. Er glaubt mit seinem Geiste in eine göttliche Harmonie eingesenkt zu sein; wenn er aber um sich sieht, so sieht er in den göttlichen Werken überall Disharmonie. Dem Menschen eignet das Licht der Weisheit; und doch ist er dem Irrtum ausgesetzt; es lebt in ihm der Trieb zum Guten, und doch klingt der Mißton des Bösen durch die ganze menschliche Entwicklung. Die Natur wird beherrscht von den großen Naturgesetzen; und doch stören Unzweckmäßigkeiten und ein wilder Kampf der Elemente ihren Einklang. Wie ist die Disharmonie in dem harmonischen Weltganzen zu begreifen. Diese Frage quält Jacob Böhme. Sie tritt in den Mittelpunkt seiner Vorstellungswelt. Er will eine Anschauung von dem Weltganzen gewinnen, welche das Disharmonische mit umschließt. Denn wie sollte eine Vorstellung die Welt erklären, welche das vorhandene Disharmonische unerklärt liegen ließe? Die Disharmonie muß aus der Harmonie, das Böse aus dem Guten selbst erklärt werden. Beschränken wir uns, indem wir von diesen Dingen reden, auf das Gute und Böse, in dem die Disharmonie im engeren Sinne im Menschenleben ihren Ausdruck findet. Denn Jacob Böhme beschränkt sich im Grunde darauf. Er kann es, denn ihm erscheinen Natur und Mensch als Eine Wesenheit. Er sieht in beiden ähnliche Gesetze und Vorgänge. Das Unzweckmäßige ist ihm ein Böses in der Natur, wie ihm das Böse ein Unzweckmäßiges im Menschenschicksal ist. Die gleichen Grundkräfte walten da und dort. Wer den Ursprung des Bösen im Menschen erkannt hat, vor dem liegt auch derjenige des Bösen in der Natur offen. - Wie kann nun aus dem gleichen Urwesen das Böse wie das Gute fließen? Wenn man im Sinne Jacob Böhmes spricht, so gibt man die folgende Antwort. Das Urwesen lebt sein Dasein nicht in sich aus. Die Mannigfaltigkeit der Welt nimmt an diesem Dasein teil. Wie der menschliche Leib sein Leben nicht als einzelnes Glied, sondern als eine Vielheit von Gliedern lebt, so auch das Urwesen. Und wie das menschliche Leben in diese Vielheit von Gliedern ausgegossen ist, so das Urwesen in die Mannigfaltigkeit der Dinge dieser Welt. So wahr es ist, daß der ganze Mensch ein Leben hat, so wahr ist es, daß jedes Glied sein eigenes Leben hat. Und so wenig es dem ganzen harmonischen Leben des Menschen widerspricht, daß seine Hand sich gegen den eigenen Leib kehrt und diesen verwundet, so wenig ist es unmöglich, daß die Dinge der Welt, die das Leben des Urwesens auf ihre eigene Weise leben, sich gegeneinander kehren. Also schenkt das Uneben, indem es sich auf verschiedene Leben verteilt, einem jeglichen Leben die Fähigkeit, sich gegen das Ganze zu kehren. Nicht aus dem Guten strömt das Böse, sondern aus der Art, wie das Gute lebt. Wie das Licht nur zu scheinen vermag, wenn es die Finsternis durchdringt, so vermag das Gute sich nur zum Leben zu bringen, wenn es seinen Gegensatz durchsetzt. Aus dem «Ungrunde» der Finsternis heraus erstrahlt das Licht; aus dem «Ungrunde» des Gleichgültigen gebiert sich das Gute. Und wie im Schatten nur die Helligkeit den Hinweis auf das Licht verlangt; die Finsternis aber selbstverständlich als das Licht schwächend empfunden wird: so wird auch in der Welt nur die Gesetzmäßigkeit in allen Dingen gesucht, und das Böse, das Unzweckmäßige als das Selbstverständliche hingenommen. Trotzdem also für Jacob Böhme das Urwesen das All ist, so kann doch nichts in der Welt verstanden werden, wenn man nicht das Urwesen und seinen Gegensatz zugleich im Auge hat. «Das Gute hat das Böse oder Widerwärtige in sich verschlungen... Jedes Wesen hat in sich Gutes und Böses, und in seiner Auswicklung, indem es sich in Schiedlichkeit führt, wird es ein Contrarium der Eigenschaften, da eine die andere zu überwältigen sucht.» Es ist daher durchaus im Sinne Jacob Böhmes, in jedem Ding und Vorgang der Welt Gutes und Böses zu sehen; aber es ist nicht in seinem Sinne, ohne weiteres, in der Vermischung des Guten mit dem Bösen das Urwesen zu suchen. Das Urwesen mußte das Böse verschlingen; aber das Böse ist nicht ein Teil des Urwesens. Jacob Böhme sucht den Urgrund der Welt; die Welt selbst aber ist durch den Urgrund aus dem Ungrund entsprungen. «Die äußere Welt ist nicht Gott, wird auch ewig nicht Gott genannt, sondern nur ein Wesen, darin sich Gott offenbart ... Wenn man sagt: Gott ist alles, Gott ist Himmel und Erde und auch die äußere Welt, so ist das wahr; denn von ihm und in ihm urständet alles. Was mache ich aber mit einer solchen Rede, die keine Religion ist?» - Mit solcher Anschauung im Hintergrunde erbauten sich in Jacob Böhmes Geist seine Vorstellungen über das Wesen aller Welt, indem er in einer Stufenfolge die gesetzmäßige Welt aus dem Ungrunde erstehen läßt. In sieben Naturgestalten erbaut sich diese Welt. In dunkler Herbigkeit erhält das Urwesen Gestalt, stumm in sich verschlossen und regungslos. Unter dem Symbol des Salzes begreift Böhme diese Herbigkeit. Er lehnt sich mit solchen Bezeichnungen an Paracelsus an, der den chemischen Vorgängen die Namen für den Naturprozeß entlehnt hat (vgl. oben S. 116f.). Durch die Verschlingung ihres Gegensatzes tritt die erste Naturgestalt in die Form der zweiten ein; das Herbe, Regungslose nimmt die Bewegung auf; Kraft und Leben tritt in sie. Das Quecksilber ist Symbol für diese zweite Gestalt. In dem Kampf der Ruhe und Bewegung, des Todes mit dem Leben, enthüllt sich die dritte Naturgestalt (Schwefel). Dieses in sich kämpfende Leben wird sich offenbar; es lebt fortan nicht mehr einen äußeren Kampf seiner Glieder; es durchbebt wie ein einheitlich leuchtender Blitz sich selbst erhellend sein Wesen (Feuer). Diese vierte Naturgestalt steigt auf zur fünften, dem in sich ruhenden lebendigen Kampf der Teile (Wasser). Auf dieser Stufe ist eine innere Herbigkeit und Stummheit wie auf der ersten vorhanden; nur ist es nicht eine absolute Ruhe, ein Schweigen der inneren Gegensätze, sondern eine innere Bewegung der Gegensätze. Es ruht in sich nicht das Ruhige, sondern das Bewegte, das durch den Feuerblitz der vierten Stufe Entzündete. Auf der sechsten Stufe wird sich die Urwesenheit selbst als solches inneres Leben gewahr; sie nimmt sich durch Sinnesorgane wahr. Die mit Sinnen begabten Lebewesen stellen diese Naturgestalt dar. Jacob Böhme nennt sie Schall oder Hall und setzt damit die Sinnesempfindung des Tones für das sinnliche Wahrnehmen als Symbol. Die siebente Naturgestalt ist der auf Grund seiner Sinneswahrnehmungen sich erhebende Geist (die Weisheit). Er findet sich innerhalb der im Ungrunde erwachsenen, aus Harmonischem und Disharmonischem sich gestaltenden Welt als sich selbst, als Urgrund wieder. «Der heilige Geist führt den Glanz der Majestät in die Wesenheit, darinnen die Gottheit offenbar steht.» Mit solchen Anschauungen sucht Jacob Böhme die Welt zu ergründen, die ihm, nach dem Wissen seiner Zeit, für die tatsächliche gilt. Für ihn sind Tatsachen die von der Naturwissenschaft seiner Zeit und von der Bibel als solche angesehenen. Ein anderes ist seine Vorstellungsart, ein anderes seine Tatsachenwelt. Man kann sich die erstere auf eine ganz andere Tatsachenerkenntnis angewendet denken. Und so erscheint vor unserem Geiste ein Jacob Böhme, wie er auch an der Grenzscheide des neunzehnten und zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts leben könnte. Ein solcher würde mit seiner Vorstellungsart nicht das biblische Sechstagewerk und den Kampf der Engel und Teufel durchdringen, sondern Lyells geologische Erkenntnisse und die Tatsache der «Natürlichen Schöpfungsgeschichte» Haeckels. Wer in den Geist von Jacob Böhmes Schriften dringt, der muß zu dieser Ãœberzeugung kommen. (Es seien die wichtigsten dieser Schriften genannt: «Die Morgenröthe im Aufgang.» «Die drei Prinzipien göttlichen Wesens.» «Vom dreifachen Leben des Menschen.» «Das umgewandte Auge.» «Signatura rerum oder von der Geburt und Bezeichnung aller Wesen.» «Mysterium magnum.») 1Dieser Satz darf nicht so vetstanden werden, als ob in der Gegenwart die Erforschung der Bibel und der geistigen Welt eine Verirrung sei; gemeint ist, daß ein «Jacob Böhme des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts» durch ähnliche Wege, wie sie den des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts zur Bibel führten, zu der «natürlichen Schöpfungsgeschichte» geführt würde. Aber er würde von da aus zur geistigen Welt vordringen.

V. Valentin Weigel and Jacob Böhme

[ 1 ] Paracelsus was primarily interested in gaining ideas about nature that breathed the spirit of the higher knowledge he advocated. A thinker related to him who applied the same way of thinking preferably to man's own nature is Valentin Weigel (1533-1588). He grew out of Protestant theology in much the same way as Eckhart, Tauler and Suso grew out of Catholic theology. He had predecessors in Sebastian Frank and Caspar Schwenckfeldt. In contrast to the outward confession of church faith, they pointed to the deepening of the inner life. For them, it is not the Jesus preached by the gospel that is valuable, but the Christ who can be born in every person from their deeper nature and who should be their savior from the lower life and guide to ideal elevation. Weigel quietly and modestly administered his pastorate in Zschopau. It was only from the writings he left behind, printed in the seventeenth century, that we learned something of the important ideas he had about the nature of man. (Of his writings, the following should be mentioned: "Der güldene Griff; das ist: All Ding ohne Irrthumb zu erkennen, vieler Hochgelährten unbekannt, und doch allen Menschen nothwendig zu wissen.") "Know thyself." - "From the place of the world.") Weigel was compelled to clarify his relationship to the teachings of the Church. This leads him to examine the foundations of all knowledge. Whether man can recognize something through a profession of faith is something he can only account for if he knows how he recognizes. Weigel starts from the lowest kind of cognition. He asks himself: how do I recognize a sensual thing when it only appears to me? From there he hopes to be able to ascend to the point of view where he can give an account of the highest cognition. - In sensory cognition, the tool (sense organ) and the thing, the "counter-throw", are opposed to each other. "Because in natural cognition there must be two things, as the object or counter-throw, which is to be recognized and seen by the eye; and the eye, or the cognizer, which sees and recognizes the object, so hold against each other: whether the cognition comes from the object into the eye; or whether the judgment and the cognition flow from the eye into the object." ("Der güldene Griff", ch. 9) Now Weigel says to himself: If cognition were to flow from the counter-throw (thing) into the eye, then an equal and perfect cognition would necessarily have to come from one and the same thing into all eyes. However, this is not the case; instead, each person sees according to his own eyes. Only the eyes, not the opposite, can be responsible for the fact that many different perceptions of one and the same thing are possible. To clarify the matter, Weigel compares seeing with reading. If the book were not there, of course I could not read it; but it could still be there, and yet I could not read anything in it if I did not understand the art of reading. The book must therefore be there; but it cannot, of itself, give me the least thing; I must extract from myself all that I read. This is also the essence of natural (sensual) knowledge. Color is there as a "counter-throw"; but of itself it can give nothing to the eye. The eye must recognize of itself what the color is. Just as little as the content of the book is in the reader, so little is the color in the eye. If the content of the book were in the reader, he would not need to read it. Nevertheless, when reading, this content does not flow out of the book, but out of the reader. It is the same with the sensual thing. What this sensual thing is outside does not flow into the person from outside, but from within. - Based on these thoughts, one could say: If all knowledge flows from the human being into the object, then one does not recognize what is in the object, but only what is in the human being himself. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) provided a detailed elaboration of this train of thought. (The falsity of this train of thought can be found in my book "Philosophy of Freedom". Here I must confine myself to mentioning that Valentin Weigel, with his simple, original way of thinking, stands much higher than Kant). - Weigel says to himself: "Even if knowledge flows out of man, it is only the essence of the counter-thought that emerges from it in a roundabout way through man. Just as I experience the contents of the book through reading, and not my own, so I experience the color of the counter-throw through the eye; not the color that is in the eye or in me. In his own way, Weigel thus arrives at a result that we have already encountered in Nicolaus von Kues. Thus Weigel has enlightened himself about the nature of sensory cognition. He came to the conviction that everything that external things have to tell us can only flow out of our own inner being. Man cannot behave in a suffering way if he wants to recognize sensual things and merely let them have an effect on him; rather, he must behave actively and bring knowledge out of himself. The counter-attack only awakens knowledge in the spirit. Man rises to higher knowledge when the spirit becomes its own counter-thought. It can be seen from sensory knowledge that no knowledge can flow into man from outside. Therefore, higher knowledge cannot come from outside either, but can only be awakened within. There can therefore be no external revelation, but only an inner awakening. Just as the external counter-throw waits until man confronts it, in which it can express its essence, so man, if he wants to be a counter-throw to himself, must wait until the realization of his essence is awakened in him. If in sensual cognition man must behave actively so that he can express his essence to the counter-throw, then in higher cognition man must behave suffering because he is now the counter-throw. He must receive his essence within himself. Therefore, the knowledge of the spirit appears to him as enlightenment from above. In contrast to sensual knowledge, Weigel therefore calls higher knowledge the "light of grace". This "light of grace" is in reality nothing other than the self-knowledge of the spirit in man, or the rebirth of knowledge on the higher level of vision. - Just as Nicolaus von Kues, in pursuing his path from knowledge to vision, does not really allow the knowledge he has gained to be reborn on a higher level, but rather, just as the ecclesiastical confession in which he was educated feigns such a rebirth, so it is also the case with Weigel. He leads himself onto the right path and loses it again the moment he sets foot on it. Anyone who wants to follow the path that Weigel points out can only regard him as a guide as far as the starting point.

[ 2 ] It is like the exultation of nature, which, at the peak of its development, marvels at its essence, what we hear from the works of the master shoemaker Jacob Böhme (1575-1624) from Görlitz. A man appears before us whose words have wings, woven from the blissful feeling of seeing the knowledge within him shine as higher wisdom. Jacob Böhme describes his state as a piety that only wants to be wisdom and as a wisdom that only wants to live in piety: "When I struggled and fought in God's support, a wonderful light dawned in my soul that was completely alien to wild nature, in which I first recognized what God and man were, and what God had to do with man." Jacob Böhme no longer feels like an individual personality expressing his insights; he feels like an organ of the great All-Spirit that speaks within him. The boundaries of his personality do not appear to him as boundaries of the spirit that speaks from within him. This spirit is omnipresent to him. He knows that "the sophist will rebuke him" when he speaks of the beginning of the world and its creation, "because I was not there and saw it myself. Let it be said to him that in my soul and body essence, when I was not yet the I, but when I was Adam's essence, I was there and hid my glory in Adam himself." Böhme is only able to hint at how the light burst forth within him in external parables. Once, when he was a boy on the summit of a mountain, he saw the entrance open at the top, where large red stones seemed to close the mountain, and a vessel of gold in its hollow. He is overcome by a shiver and goes his way without touching the treasure. Later, he is apprenticed to a shoemaker in Görlitz. A stranger enters the store and asks for a pair of shoes. Böhme is not allowed to sell them to him in the absence of the master. The stranger leaves, but after a while calls the apprentice out and tells him: "Jacob, you are small, but one day you will become a completely different person who will amaze the world. At a more mature age, Jacob Böhme sees the reflection of a pewter vessel in the glare of the sun: the sight that presents itself to him seems to reveal a deep secret. Ever since he was impressed by this apparition, he believed himself to be in possession of the key to the mysterious language of nature. - He lives as a spiritual hermit, modestly nourishing himself with his craft and, as if for his own memory, recording the sounds that resound within him when he feels the spirit within him. Zealot priestly zeal makes life difficult for the man. He who only wants to read the Scriptures that illuminate the light of his inner being is persecuted and tormented by those to whom only the external Scriptures, the rigid, dogmatic confession, are accessible.

[ 3 ] A world puzzle lives in Jacob Böhme's soul as a restlessness that drives him to knowledge. He believes his spirit to be immersed in a divine harmony; but when he looks around him, he sees disharmony everywhere in the divine works. Man is endowed with the light of wisdom, and yet he is subject to error; the impulse to do good lives in him, and yet the note of evil resounds through the whole of human development. Nature is governed by the great laws of nature; and yet inappropriateness and a wild struggle of the elements disturb its harmony. How is disharmony to be understood in the harmonious whole of the world? This question torments Jacob Böhme. It is at the center of his imagination. He wants to gain a view of the world as a whole that includes the disharmonious. For how could a conception explain the world that left the existing disharmony unexplained? Disharmony must be explained from harmony, evil from the good itself. In speaking of these things, let us confine ourselves to the good and evil in which disharmony in the narrower sense finds its expression in human life. For Jacob Boehme basically confines himself to this. He can, because nature and man appear to him as one entity. He sees similar laws and processes in both. To him, the inexpedient is an evil in nature, just as evil is an inexpedient in human destiny. The same basic forces are at work here and there. Whoever has recognized the origin of evil in man has also recognized the origin of evil in nature. - How can evil and good flow from the same primordial being? If one speaks in the sense of Jacob Böhme, one gives the following answer. The primordial being does not live out its existence in itself. The diversity of the world participates in this existence. Just as the human body does not live its life as a single member, but as a multiplicity of members, so does the primordial being. And just as human life is poured into this multiplicity of members, so is the primordial being poured into the multiplicity of things of this world. As true as it is that the whole human being has one life, so true is it that each member has its own life. And as little as it contradicts the whole harmonious life of man that his hand turns against his own body and wounds it, so little is it impossible that the things of the world, which live the life of the original being in their own way, turn against each other. Thus, by distributing itself among different lives, the uneven gives each life the ability to turn against the whole. Evil does not flow from the good, but from the way in which the good lives. Just as light can only shine when it penetrates the darkness, so good can only bring itself to life when it asserts its opposition. The light shines out of the "unround" of darkness; the good is born out of the "unround" of indifference. And just as in the shadow only the brightness demands a reference to the light, but the darkness is naturally perceived as weakening the light, so also in the world only the lawfulness in all things is sought, and the evil, the inappropriate is accepted as self-evident. Although for Jacob Böhme the primordial being is the universe, nothing in the world can be understood if one does not have the primordial being and its opposite in mind at the same time. "The good has swallowed up the evil or repugnant within itself... Every being has good and evil in itself, and in its development, by leading itself into diversity, it becomes a contrarium of qualities, since one seeks to overpower the other." It is therefore entirely in Jacob Böhme's sense to see good and evil in every thing and process in the world; but it is not in his sense to seek the primordial being in the mixture of good and evil without further ado. The primordial being had to devour evil; but evil is not a part of the primordial being. Jacob Boehme seeks the primordial ground of the world; but the world itself has sprung from the unground through the primordial ground. "The outer world is not God, nor will it ever be called God, but only a being in which God reveals himself ... If one says: God is everything, God is heaven and earth and also the outer world, then this is true; for everything originates from him and in him. But what do I do with such talk, which is not religion?" - With such a view in the background, his ideas about the nature of all the world were built up in Jacob Böhme's mind, in that he allows the lawful world to emerge from the unfathomable in a step-by-step sequence. This world is constructed in seven natural forms. The primordial being takes shape in dark austerity, mutely closed in on itself and motionless. Böhme understands this astringency under the symbol of salt. With such designations he borrows from Paracelsus, who borrowed the names for the natural process from the chemical processes (cf. above p. 116f.). Through the intertwining of their opposites, the first natural form enters into the form of the second; the harsh, motionless takes on the movement; power and life enter into it. Mercury is the symbol of this second form. In the struggle of rest and movement, of death with life, the third natural form (sulphur) reveals itself. This life, struggling within itself, reveals itself; from now on it no longer lives an external struggle of its limbs; it illuminates its being like a uniformly shining flash of lightning (fire). This fourth form of nature ascends to the fifth, the living struggle of the parts resting in itself (water). At this stage there is an inner austerity and muteness as at the first; only it is not an absolute calm, a silence of the inner opposites, but an inner movement of the opposites. It is not the calm that rests within itself, but the moving, that which is ignited by the flash of fire of the fourth stage. On the sixth stage, the primordial being becomes aware of itself as such an inner life; it perceives itself through sense organs. The living beings endowed with senses represent this natural form. Jacob Böhme calls it sound or reverberation and thus uses the sense sensation of sound as a symbol for sensory perception. The seventh natural form is the spirit (wisdom) that rises on the basis of its sensory perceptions. It finds itself as itself, as the primordial ground, within the world that has arisen in the primordial and is formed from the harmonious and the disharmonious. "The Holy Spirit leads the splendor of majesty into the essence in which the Godhead is revealed." With such views, Jacob Böhme seeks to fathom the world, which, according to the knowledge of his time, he considers to be the real one. For him, facts are those regarded as such by the natural science of his time and by the Bible. Another is his way of imagining, another his world of facts. One can imagine the former applied to a completely different knowledge of facts. And so a Jacob Boehme appears before our minds, as he might live on the borderline of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Such a person would not penetrate the biblical six-day work and the battle of angels and devils with his way of thinking, but Lyell's geological findings and the fact of Haeckel's "Natural History of Creation". Anyone who penetrates the spirit of Jacob Böhme's writings must come to this conviction. (The most important of these writings are: "Die Morgenröthe im Aufgang." "The three principles of divine being." "Of the threefold life of man." "The turned eye." "Signatura rerum or of the birth and designation of all beings." "Mysterium magnum.") 1This sentence must not be understood as if the study of the Bible and the spiritual world is an aberration in the present day; what is meant is that a "Jacob Boehme of the nineteenth century" would be led to the "natural history of creation" by paths similar to those that led him to the Bible in the sixteenth century. But he would proceed from there to the spiritual world.