Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age

GA 7

Agrippa of Nettesheim and Theophrastus Paracelsus

[ 1 ] The road which is indicated by the way of thinking of Nicolas of Cusa was walked by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim (1487–1535) and Theophrastus Paracelsus (1493–1541). They immerse themselves in nature and, as comprehensively as possible, seek to explore its laws with all the means their period makes available to them. In this knowledge of nature they see at the same time the true foundation for all higher cognition. They themselves seek to develop the latter out of natural science by letting science be reborn in the spirit.

[ 2 ] Agrippa of Nettesheim led an eventful life. He was descended from a noble family and was born in Cologne. He studied medicine and jurisprudence at an early age and sought to inform himself about natural phenomena in the way customary at the time in certain circles and societies, or by contact with a number of scholars who carefully kept secret whatever insights they gained into nature. With such purposes he repeatedly went to Paris, to Italy, and to England, and he also visited the famous Abbot Trithemius of Sponheim in Würzburg. He taught in scientific institutions at various times and here and there entered the services of rich and noble personages, at whose disposal he placed his talents as a statesman and scientist. If his biographers describe the services he rendered as not always above reproach, if it is said that he acquired money under the pretext of being adept in secret arts, and of securing various advantages to people by means of these arts, this is counterbalanced by his unmistakable and ceaseless urge to acquire the entire learning of his time honestly and to make this learning deeper in the spirit of a higher cognition of the world. In him distinctly appears the endeavor to achieve a clear position with regard to natural science on the one hand, with regard to higher cognition on the other. Such a position is attained only by one who has an insight into the ways by which one reaches the one and the other cognition. Just as it is true that at last natural science must be raised into the region of the spirit if it is to lead into higher cognition, so it is true that it must at first remain in the field proper to it if it is to provide the right foundation for a higher level. The “spirit in nature” exists only for the spirit. As certainly as nature is in this sense spiritual, as certain is it that nothing perceived in nature by bodily organs is immediately spiritual. Nothing spiritual can appear to my eye as being spiritual. I must not seek the spirit as such in nature. I do this when I interpret a process of the external world in an immediately spiritual way: when, for instance, I ascribe to plants a soul which is only distantly analogous to the human soul. I also do this when I ascribe a spatial or temporal existence to the spirit or the soul itself; when, for instance, I say of the eternal human soul that it lives in time without the body, but still in the manner of a body, rather than as pure spirit. Or when I even believe that the spirit of a deceased person can show itself in some kind of sensorily perceptible manifestations. Spiritualism, which commits this error, thereby only shows that it has not penetrated to the true conception of the spirit, but wants to see the spirit directly in something grossly sensory. It fails to understand the nature of the sensory as well as that of the spirit. It deprives of spirit the ordinary sensory phenomena, which take place hour by hour before our eyes, in order to consider something rare, surprising, unusual as spirit in a direct sense. It does not understand that for one who is capable of seeing the spirit, what lives as “spirit in nature” reveals itself, for instance, in the collision of two elastic spheres, and not only in processes which are striking because of their rarity and cannot be immediately grasped in their natural context. In addition, the spiritualist draws the spirit down into a lower sphere. Instead of explaining something that takes place in space and that he perceives with the senses by means of forces and beings which in turn are only spatial and sensorily perceptible, he has recourse to “spirits,” which he thus equates completely with the sensorily perceptible. Such a way of thinking is based on a lack of capacity for spiritual comprehension. One is not capable of looking at the spiritual in a spiritual manner, therefore with mere sensory beings one satisfies one's need for the presence of the spirit. To such people the spirit does not show any spirit; therefore they seek it with the senses. As they see clouds sailing through the air, so they also want to see spirits hurrying along.

[ 3 ] Agrippa of Nettesheim fights for a true natural science, which does not attempt to explain the phenomena of nature by spiritual beings which haunt the world of the senses, but sees in nature only the natural, in the spirit only the spiritual.—One would of course completely misunderstand Agrippa if one were to compare his natural science with that of later centuries, which has altogether different data at its disposal. In such a comparison it might easily appear that he still refers what is due only to natural causes, or based on erroneous data, to the direct action of spirits. Moritz Carriere does him this injustice when he says—although not with ill will—, “Agrippa gives a long list of the things which belong to the sun, the moon, the planets, or the fixed stars, and receive their influences; for instance, related to the sun are fire, blood, laurel, gold, chrysolite; they bestow the gift of the sun: courage, serenity, light ... The animals have a sense of nature which, more exalted than human reason, approaches the spirit of prophecy ... Men can be enjoined to love and hate, to sickness and health. Thus one puts a spell upon thieves that enjoins them from stealing somewhere, upon merchants so that they cannot trade, ships and mills so that they cannot move, lightning so that it cannot strike. This is done with potions, salves, images, rings, charms; the blood of hyenas or basilisks is suitable for this purpose,—one is reminded of Shakespeare's witches' cauldron.” No, one is not reminded of it, if one understands Agrippa aright. He did of course believe in things which were considered to be indubitable in his time. But we do this today also with regard to what is nowadays considered “factual.” Or is one to believe that future centuries also will not throw much of what we set up as indubitable facts into the store-room of “blind” superstition? It is true that I am convinced that there is a real progress in man's knowledge of facts. When the “fact” that the earth is round had once been discovered, all earlier suppositions were banished into the realm of “superstition.” Thus it is with certain truths of astronomy, of biology, etc. The doctrine of natural descent, in comparison with all earlier “hypotheses of creation,” represents a progress similar to the insight that the earth is round compared to all previous suppositions concerning its shape. Nevertheless I am aware that there is many a “fact” in our learned scientific works and treatises which will no more appear as fact to future centuries than does much of what is maintained by Agrippa and Paracelsus to us today. It is not a matter of what they considered to be a “fact,” but of the spirit in which they interpreted these facts.—In Agrippa's time one found, it is true, little comprehension of the “natural magic” which he advocated, and which seeks in nature the natural, and the spiritual only in the spirit; men clung to the “supernatural magic” which seeks the spiritual in the realm of the sensory, and against which Agrippa fought. This is why the Abbot Trithemius of Sponheim advised him to communicate his views as a secret doctrine only to a few chosen ones, who were able to rise to a similar conception of nature and spirit, for “one gives only hay to oxen and not sugar, as to songbirds.” It is perhaps to this abbot that Agrippa himself owes the right point of view. In his Steganographie, Steganography, Trithemius has written a work in which he treats, with the most veiled irony, the way of thinking which confounds nature with the spirit. In this book he appears to speak entirely of supernatural phenomena. One who reads it as it stands must believe that the author is speaking of the conjuring of spirits, of the flying of spirits through the air, etc. But if one omits certain words and letters of the text there remain, as Wolfgang Ernst Heidel showed in the year 1676, letters which, when assembled into words, describe purely natural phenomena. (In one case for instance, in a formula of incantation, one must completely omit the first and the last word, and then cross out the second, fourth, sixth, etc. of those remaining. In the remaining words one must again cross out the first, third, fifth, etc. letter. What remains, one then assembles into words, and the formula of incantation is transformed into a communication of a purely natural content.)

[ 4 ] How difficult it was for Agrippa to work his way out of the prejudices of his time and to raise himself to a pure conception, is proven by the fact that he did not let his Philosophia occulta, Secret Philosophy, appear until the year 1531, although it had been composed as early as 1510, because he considered it to be immature. Further evidence of this is given in his work, De vanitate scientiarum, Of the Vanity of the Sciences, where he speaks with bitterness about the scientific and general activity of his time. There he says quite plainly that only with difficulty has he liberated himself from the delusion of those who see in external events direct spiritual processes, in external facts prophetic hints about the future, etc. Agrippa proceeds to the higher cognition in three stages. At the first stage he deals with the world as it is presented to the senses, with its substances, and its physical, chemical, and other forces. Insofar as it is viewed at this stage he calls nature elemental. At the second stage one regards the world as a whole in its natural connections, in the way it arranges everything belonging to it according to measurements, number, weight, harmony, etc. The first stage brings those things together which are in close proximity to each other. It seeks the causes of a phenomenon which lie in its immediate environment. The second stage looks at a single phenomenon in connection with the whole universe. It carries out the idea that each thing is under the influence of all the remaining things of the universal whole. This universal whole appears to it as a great harmony, of which every separate entity is a part. The world, seen from this point of view, is designated by Agrippa as the astral or celestial one. The third stage of cognition is that where the spirit, through immersion in itself, looks directly upon the spiritual, the primordial essence of the world. Here Agrippa speaks of the spiritual-soul world.

[ 5 ] The views which Agrippa developed about the world and man's relationship to it we encounter in a similar, but more complete form in Theophrastus Paracelsus. They are therefore better considered in connection with the latter.

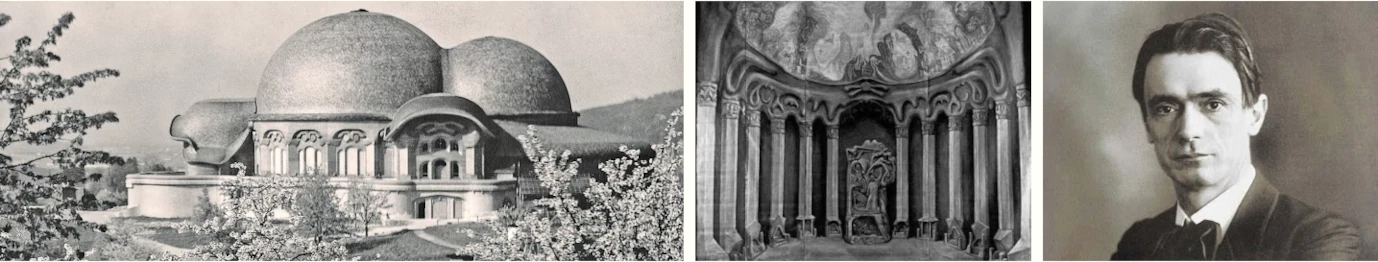

[ 6 ] Paracelsus characterizes himself when he writes under his portrait, “No one who can stand alone by himself should be the servant of another.” His whole position with regard to cognition is given in these words. Everywhere he himself wants to go back to the foundations of natural science in order to ascend, through his own powers, to the highest regions of cognition. As a physician he does not simply want to accept, like his contemporaries, what the old investigators who at the time were considered authorities, as for instance Galen or Avicenna, had affirmed in times gone by; he himself wants to read directly in the book of nature. “The physician must pass through the examination of nature, which is the world, and all its causation. And what nature teaches him he must commend to his wisdom, not seeking anything in his wisdom, but only in the light of nature.” He does not recoil from anything in order to become acquainted with nature and its manifestations from all sides. For this purpose he travels to Sweden, Hungary, Spain, Portugal, and the Orient. He can say of himself, “I have pursued the art in danger of my life and have not been ashamed to learn from strollers, hangmen, and barbers. My teachings have been tested more severely than silver in poverty, anxiety, wars, and perils.” What has been handed down from old authorities has no value for him, for he believes that he can only attain the right conception if he himself experiences the ascent from natural science to the highest cognition. This experiencing in his own person puts the proud words in his mouth, “One who wants to pursue the truth must come into my realm ... After me, not I after you, Avicenna, Rhases, Galen, Mesur! After me, and I not after you, you of Paris, you of Montpellier, you of Swabia, you of Meissen, you of Cologne, you of Vienna, and whatever lies on the Danube and the river Rhine, you islands in the sea, you Italy, you Dalmatia, you Athens, you Greek, you Arab, you Israelite; after me, and I not after you! Mine is the realm!”—It is easy to misjudge Paracelsus because of his rough exterior, which sometimes hides deep seriousness behind jest. He himself says, “Nature has not made me subtle, nor have I been raised on figs and white bread, but rather on cheese, milk, and oat bread, and therefore I may well be uncivil to the hyperclean and the superfine; for those who were brought up in soft clothes and we, who were brought up among fir-cones, do not understand each other well. Thus I must seem rough, though to myself I appear gracious. How can I not be strange for one who has never gone wandering in the sun?”

[ 7 ] Goethe has described the relationship of man to nature (in his book on Winkelmann) in the following beautiful sentences: “When the healthy nature of man acts as a whole, when he feels himself to be in the world as in a great, beautiful, noble, and valued whole, when harmonious ease affords him a pure and free delight, then the universe, if it could experience itself, would exult, as having attained its goal, and admire the climax of its own becoming and essence.” Paracelsus is deeply penetrated with a sentiment like the one that expresses itself in such sentences. Out of this sentiment the mystery of man shapes itself for him. Let us see how this happens, in Paracelsus' sense. At first the road which nature has taken in order to bring forth its highest achievement is hidden from the human powers of comprehension. It has attained this climax; but this climax does not say, I feel myself to be the whole of nature; this climax says, I feel myself to be this single man. What in reality is an act of the whole world feels itself to be a single, solitary being, standing by itself. Indeed, this is the true nature of man, that he must feel himself as being something other than what, in the final analysis, he is. And if this is a contradiction, then man can be called a contradiction come to life. Man in his own way is the world. His harmony with the world he regards as a duality. He is the same as the world is, but he is this as a repetition, as a separate being. This is the contrast which Paracelsus perceives as microcosm (man) and macrocosm (universe). For him man is the world in little. What causes man to regard his relationship with the world in this way is his spirit. This spirit appears to be bound to a single being, to a single organism. By its whole nature, this organism belongs to the great chain of the universe. It is a link in it, and has its existence only in connection with all the others. The spirit, however, appears to be an outcome of this single organism. At first it sees itself as connected only with this organism. It tears this organism loose from the native soil out of which it grew. For Paracelsus a deep connection between man and the entire universe thus lies hidden in the natural foundation of existence, a connection which is obscured by the presence of the spirit. For us humans, the spirit, which leads us to higher cognition by communicating knowledge to us and by causing this knowledge to be reborn on a higher level, has at first the effect of obscuring for us our own connection with the universe. For Paracelsus human nature thus at first falls into three parts: into our sensory-corporeal nature, our organism, which appears to us as a natural being among other natural beings, and which is just like all other natural beings; into our hidden nature, which is a link in the chain of the whole world, which thus is not enclosed within our organism, but sends out and receives influences to and from the whole universe; and into the highest nature, our spirit, which lives its life only in a spiritual manner. The first part of human nature Paracelsus calls the elemental body; the second the ethereal-celestial or “astral body;” the third part he calls soul.—In the “astral” phenomena Paracelsus thus sees an intermediate level between the purely corporeal phenomena and the true phenomena of the soul. They will become visible when the spirit, which obscures the natural foundation of our existence, ceases its activity. We can see the simplest manifestation of this realm in the world of dreams. The images which flit through our dreams, with their peculiar, significant connection with events in our environment and with our own internal states, are products of our natural foundation which are obscured by the brighter light of the soul. When a chair collapses near my bed, and I dream a whole drama, which ends with a shot fired in a duel, or when I have palpitations of the heart, and dream of a seething stove, then meaningful and significant natural manifestations are appearing which reveal a life lying between the purely organic functions and the thinking processes taking place in the bright consciousness of the spirit. With this realm are connected all the phenomena which belong to the field of hypnotism and of suggestion. In suggestion we can see an acting of man on man, which points to an interrelationship between beings in nature that is obscured by the higher activity of the spirit. In this connection it becomes possible to understand what Paracelsus interprets as an “astral body.” It is the sum of the natural influences to which we are exposed or can be exposed through special circumstances, which emanate from us without involving our soul, and which nevertheless do not fall under the concept of purely physical phenomena. That in this field Paracelsus enumerates facts which we doubt today, has no importance when looked at from the point of view I have already adduced above.—On the basis of such views of human nature Paracelsus divides the latter into seven parts. They are the same as we find in the teachings of the ancient Egyptians, among the Neoplatonists, and in the Cabala. Man is first of all a physical-corporeal being; hence he is subject to the same laws to which every body is subject. In this sense he is thus a purely elemental body. The purely corporeal-physical laws combine in the organic life process. Paracelsus designates the organic laws as “Archaeus” or “Spiritus vitae;” the organic raises itself to spiritlike manifestations which are not yet spirit. These are the “astral” manifestations. From the “astral” processes emerge the functions of the “animal spirit.” Man is a sense being. He combines his sensory impressions in a rational manner by means of his reason. Thus the “rational soul” awakens in him. He immerses himself in his own spiritual products; he learns to recognize the spirit as spirit. Therewith he has raised himself to the level of the “spiritual soul.” At last he understands that in this spiritual soul he experiences the deepest stratum of the universal existence; the spiritual soul ceases to be an individual, separate one. The insight takes place of which Eckhart spoke when he felt that it was no longer he himself who spoke in him, but the primordial essence. Now that condition prevails in which the universal spirit regards itself in man. Paracelsus has expressed the feeling aroused by this condition in the simple words: “And this which you must consider is something great: there is nothing in Heaven and on earth which is not in man. And God, who is in Heaven, is in man.”—It is nothing but facts of external and internal experience that Paracelsus wants to express with these seven fundamental parts of human nature. That what for human experience falls into a plurality of seven parts is in higher reality a unity, is not thereby brought into question. The higher cognition exists precis to show the unity in everything which in his immediate experience appears to man as a plurality because of his corporeal and spiritual organization. On the level of the highest cognition Paracelsus strives to fuse the living, uniform, primordial essence of the world with his spirit. But he knows that man can only know nature in its spirituality if he enters into immediate intercourse with it. Man does not understand nature by peopling it, on his own, with arbitrarily assumed spiritual entities, but by accepting and valuing it as it is as nature. Paracelsus therefore does not seek God or the spirit in nature; but for him nature, as it presents itself to his eye, is immediately divine. Must one first attribute to the plant a soul like the human soul in order to find the spiritual? Therefore Paracelsus explains the development of things, insofar as this is possible with the scientific resources of his time, entirely in such a way that he regards this development as a sensory process of nature. He lets everything arise out of the primordial matter, the primordial water (Yliaster). And he regards as a further process of nature the separation of the primordial matter (which he also calls the great limbus) into the four elements, water, earth, fire, and air. When he says that the “divine word” called forth the plurality of beings from the primordial matter, this is only to be understood in somewhat the same manner as the relationship of force to matter is to be understood in modern natural science. A “spirit” in the real sense is not yet present on this level. This “spirit” is not an actual cause of the natural process, but an actual result of this process. This spirit does not create nature, but develops out of it. Many words of Paracelsus could be interpreted in the opposite sense. Thus, for instance, he says: “There is nothing corporeal that does not carry a living spirit hidden within it. And not only that has life which stirs and moves, such as men, animals, the worms in the earth, the birds in the sky, and the fish in the water, but all corporeal and substantial things.” But with such sayings Paracelsus only wants to warn against the superficial view of nature which thinks that it can exhaust the nature of a thing with a few “rammed-in” concepts (to use Goethe's apt expression). He does not want to inject an invented nature into things, but rather to set all the faculties of man in motion in order to bring forth what actually lies within a thing.—It is important not to let oneself be misled by the fact that Paracelsus expresses himself in the spirit of his time. Rather, one should try to understand what he has in mind when, looking upon nature, he sets forth his ideas in the forms of expression of his time. For instance, he ascribes to man a twofold flesh, that is, a twofold corporeal constitution. “The flesh must therefore he understood to be of two kinds, namely, the flesh whose origin is in Adam, and the flesh which is not from Adam. The flesh that is from Adam is a coarse flesh, for it is earthly and nothing but flesh, and is to be bound and grasped like wood and stone. The other flesh is not from Adam; it is a subtle flesh and is not to be bound or grasped, for it is not made of earth.” What is the flesh that is from Adam? It is all that has come down to man through his natural development, which he has therefore inherited. To this is added what in the course of time man has acquired for himself in intercourse with his environment. The modern scientific concepts of inherited characteristics and of characteristics acquired through adaptation emerge from the above-mentioned thought of Paracelsus. The “subtler flesh,” which makes man capable of spiritual activities, has not been in man from the beginning. He was “coarse flesh” like the animals, a flesh that “is to be bound and grasped like wood and stone.” In the scientific sense the soul is therefore also an acquired characteristic of the “coarse flesh.” What the natural scientist of the nineteenth century has in mind when he speaks of the inheritances from the animal world, is what Paracelsus means when he uses the expression about “the flesh whose origin is in Adam.” These remarks, of course, are not intended to obliterate the difference which exists between a natural scientist of the sixteenth and one of the nineteenth century. After all, it was only the latter century which was capable of seeing, in the full scientific sense, the forms of living organisms in such a connection that their natural relationship and their actual descent as far as man became evident. Science sees only a natural process where Linnè in the eighteenth century still saw a spiritual process, which he characterized in the following words: “There are as many species of living organisms as there were, in principle, forms that were created.” While Linnè thus had to transfer the spirit into the spatial world and assign to it the task of producing spiritually, of “creating” the forms of life, the natural science of the nineteenth century could ascribe to nature what is nature's and to the spirit what is the spirit's. Nature itself is assigned the task of explaining its creations, and the spirit can immerse itself into itself where it alone is to be found, within man.—But while in a certain sense Paracelsus thinks quite in the spirit of his time, yet just with regard to the idea of development, of becoming, he has grasped the relationship of man to nature in a profound manner. In the primordial essence of the world he did not see something which in some way exists as something finished, but he grasped the divine in its becoming. Hence he could really ascribe a self-creating activity to man. If the divine primordial essence exists, once and for all a true creating by man is out of the question. Then it is not man, who lives in time, who creates, but God, Who is eternal. For Him there is only an eternal becoming, and man is a link in this eternal becoming. That which man forms did not previously exist in any way. What man creates, as he creates it, is an original creation. If it is to be called divine, this can only be in the sense in which it exists as a human creation. Therefore in the building of the universe Paracelsus can assign to man a role which makes him a co-architect in this creation. The divine primordial essence without man is not what it is with man. “For nature brings forth nothing into the light of day which is complete as it stands; rather, man must complete it.” This self-creating activity of man in the building of nature, Paracelsus calls alchemy. “This completion is alchemy. Thus the alchemist is the baker when he bakes the bread, the vintager when he makes the wine, the weaver when he makes the cloth.” Paracelsus wants to be an alchemist in his field, as a physician. “Therefore I may well write so much here concerning alchemy, so that you can know it well and learn what it is and how it is to be understood, nor be vexed that it is to bring you neither gold nor silver. Rather see that the arcana (remedies) are revealed to you ... The third pillar of medicine is alchemy, for the preparation of remedies cannot take place without it, because nature cannot be put to use without art.”

[ 8 ] Thus Paracelsus' eyes are directed in the strictest sense upon nature, in order to discover from nature itself what it has to say about its products. He wants to investigate the laws of chemistry in order to work as an alchemist in his sense. He considers all bodies to be composed of three basic substances, namely, of salt, sulphur, and mercury. What he so designates of course does not correspond to what later chemistry designates by this name, any more than what Paracelsus considers to be a basic substance is one in the sense of later chemistry. Different things are designated by the same names at different times. What the ancients called the four elements, earth, water, air, and fire, we still have. We call these four “elements” no longer “elements” but states of aggregation, for which we have the designations: solid, liquid, aeriform, etheriform. Earth, for instance, for the ancients was not earth but the “solid.” The three basic substances of Paracelsus we can also recognize in contemporary concepts, but not under the homonymous contemporary names. For Paracelsus, solution in a liquid and combustion are the two important chemical processes of which he makes use. If a body is dissolved or burned it is decomposed into its parts. Something remains as residue; something is dissolved or burns. For him the residue is salt-like, the soluble (liquid), mercury-like; the combustible he calls sulphurous.

[ 9 ] One who does not look beyond such natural processes may be left cold by them as by things of a material and prosaic nature; one who at all costs wants to grasp the spirit with the senses will people these processes with all kinds of spiritual beings. But like Paracelsus, one who knows how to look at such processes in connection with the universe, which reveals its secret within man, accepts these processes as they present themselves to the senses; he does not first reinterpret them; for as the natural processes stand before us in their sensory reality, in their own way they reveal the mystery of existence. What through this sensory reality these processes reveal out of the soul of man, occupies a higher position for one who strives for the light of higher cognition than do all the supernatural miracles concerning their so-called “spirit” which man can devise or have revealed to him. There is no “spirit of nature” which can utter more exalted truths than the great works of nature themselves, when our soul unites itself with this nature in friendship, and, in familiar intercourse, hearkens to the revelations of its secrets. Such a friendship with nature, Paracelsus sought.

IV. Agrippa von Nettesheim und Theophrastus Paracelsus

[ 1 ] Den Weg, auf welchen die Vorstellungsweise des Nicolaus von Kues hinweist, sind Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1487-1535) und Theophrastus Paracelsus (1493-1541) gewandelt. Sie vertiefen sich in die Natur und suchen deren Gesetze mit allen Mitteln, die ihnen ihre Zeitepoche darbietet, zu erforschen, und zwar so allseitig wie möglich. In diesem Naturwissen sehen sie zugleich die wahre Grundlage für alle höhere Erkenntnis. Diese suchen sie aus der Naturwissenschaft heraus selbst zu entwickeln, indem sie diese im Geiste wiedergeboren werden lassen.

[ 2 ] Agrippa von Nettesheim führte ein wechselreiches Leben. Er stammt aus einem vornehmen Geschlecht und ist in Köln geboren. Er studierte frühzeitig Medizin und Rechtswissenschaft und suchte sich über die Naturvorgänge in der Art aufzuklären, wie es damals üblich war innerhalb gewisser Kreise und Gesellschaften, oder auch bei einzelnen Forschern, die, was ihnen an Naturkenntnis aufging, sorgfältig geheim hielten. Er ging zu solchen Zwecken wiederholt nach Paris, nach Italien und England, und besuchte auch den berühmten Abt Trithem von Sponheim in Würzburg. Er lehrte zu verschiedenen Zeiten in wissenschaftlichen Anstalten und trat da und dort in die Dienste von Reichen und Vornehmen, denen er seine staatsmännischen und naturwissenschaftlichen Geschicklichkeiten zur Verfügung stellte. Wenn von seinen Biographen die Dienste, die er geleistet hat, als nicht immer einwandfrei geschildert werden, wenn gesagt wird, daß er unter dem Vorgeben, geheime Künste zu verstehen und durch sie den Menschen Vorteile zu verschaffen, sich Geld erworben habe, so steht dem sein unverkennbarer, rastloser Trieb gegenüber, sich das gesamte Wissen seiner Zeit in ehrlicher Weise anzueignen und dieses Wissen im Sinne einer höheren Welterkenntnis zu vertiefen. Deutlich tritt bei ihm das Bestreben zutage, eine klare Stellung zur Naturwissenschaft auf der einen Seite, zur höheren Erkenntnis auf der anderen Seite zu gewinnen. Zu einer solchen Stellung gelangt nur, wer Einsicht darin hat, auf welchen Wegen man zu der einen und zur anderen Erkenntnis gelangt. So wahr es ist, daß die Naturwissenschaft zuletzt in die Region des Geistes heraufgehoben werden muß, wenn sie in höhere Erkenntnis übergehen soll, so wahr ist es auch, daß sie zunächst auf dem ihr eigentümlichen Felde bleiben muß, wenn sie die rechte Grundlage für eine höhere Stufe abgeben soll. Der «Geist in der Natur» ist nur für den Geist da. So gewiß die Natur in diesem Sinne geistig ist, so gewiß ist nichts in der Natur unmittelbar geistig, was von körperlichen Organen wahrgenommen wird. Es gibt nichts Geistiges, das meinem Auge als Geistiges erscheinen kann. Ich darf den Geist als solchen nicht in der Natur suchen. Das tue ich, wenn ich einen Vorgang der äußeren Welt unmittelbar geistig deute, wenn ich z.B. der Pflanze eine Seele zuschreibe, die nur entfernt analog der Menschenseele sein soll. Das tue ich ferner auch, wenn ich dem Geist oder der Seele selbst ein räumliches oder zeitliches Dasein zuschreibe, wenn ich z.B. von der ewigen Menschenseele sage, daß sie ohne den Körper, aber doch nach Art eines Körpers, statt als reiner Geist, in der Zeit fortlebe. Oder wenn ich gar glaube, daß in irgendwelchen sinnlich-wahrnehmbaren Veranstaltungen der Geist eines Verstorbenen sich zeigen könne. Der Spiritismus, der diesen Fehler begeht, zeigt damit nur, daß er bis zur wahrhaften Vorstellung des Geistes nicht vorgedrungen ist, sondern in einem Grobsinnlichen unmittelbar den Geist anschauen will. Er verkennt sowohl das Wesen des Sinnlichen wie dasjenige des Geistes. Er entgeistet das gewöhnliche Sinnliche, das Stunde für Stunde sich vor unseren Augen abspielt, um ein Seltenes, Ãœberraschendes, Ungewöhnliches unmittelbar als Geist anzusprechen. Er begreift nicht, daß, was als «Geist in der Natur» lebt, sich z.B. beim Stoß zweier elastischer Kugeln für denjenigen, der Geist zu sehen vermag, enthüllt; und nicht erst bei Vorgängen, die durch ihre Seltenheit frappieren und die in ihrem natürlichen Zusammenhange nicht sofort überschaubar sind. Der Spiritist zieht aber auch den Geist in eine niedere Sphäre herab. Statt etwas, das im Raume vorgeht und das er mit den Sinnen wahrnimmt, auch durch Kräfte und Wesen zu erklären, die nur wieder räumlich und sinnlich wahrnehmbar sind, greift er zu «Geistern», die er somit völlig gleichsetzt mit dem Sinnlich-Wahrnehmbaren. Es liegt einer solchen Vorstellungsart ein Mangel an geistigem Auffassungsvermögen zugrunde. Man ist nicht imstande, Geistiges auf geistige Art anzuschauen; deshalb befriedigt man sein Bedürfnis nach dem Vorhandensein des Geistes mit bloßen Sinnenwesen. Der Geist zeigt solchen Menschen keinen Geist; deshalb suchen sie ihn mit den Sinnen. Wie sie Wolken durch die Luft fliegen sehen, möchten sie auch Geister dahineilen sehen.

[ 3 ] Agrippa von Nettesheim kämpft für eine echte Naturwissenschaft, welche die Erscheinungen der Natur nicht durch Geisteswesen, die in der Sinneswelt spuken, erklären will, sondern welche in der Natur nur Natürliches, im Geiste nur Geistiges sehen will. - Man wird natürlich Agrippa völlig mißverstehen, wenn man seine Naturwissenschaft mit derjenigen späterer Jahrhunderte vergleicht, die über ganz andere Erfahrungen verfügt. Bei solcher Vergleichung könnte leicht scheinen, daß er noch durchaus auf unmittelbare Geisterwirkungen bezieht, was nur auf natürlichen Zusammenhängen oder auf falscher Erfahrung beruht. Ein solches Unrecht fügt Moritz Carriere ihm zu, wenn er - allerdings nicht im übelwollenden Sinne - sagt: «Agrippa gibt ein großes Register der Dinge, welche der Sonne, dem Mond, den Planeten oder Fixsternen zugehören und Einflüsse von ihnen empfangen; z.B. der Sonne verwandt ist das Feuer, das Blut, der Lorbeer, das Gold, der Chrysolit; sie verleihen die Gabe der Sonne: Mut, Heiterkeit, Licht... Die Tiere haben einen Natursinn, der erhabener als der menschliche Verstand sich dem Geiste der Weissagung nähert... Es können Menschen zu Lieb' und Haß, zu Krankheit und Gesundheit gebunden werden. So bindet man Diebe, daß sie irgendwo nicht stehlen, Kaufleute, daß sie nicht handeln, Schiffe, Mühlen, daß sie nicht gehen, Blitze daß sie nicht treffen können. Es geschieht durch Tränke, Salben, Bilder, Ringe, Bezauberungen; das Blut von Hyänen oder Basilisken eignet sich zu solchem Gebrauch - es gemahnt an Shakespeares Hexenkessel.» Nein, es gemahnt nicht daran, wenn man Agrippa richtig versteht. Er glaubte selbstverständlich an Tatsachen, die man in seiner Zeit nicht bezweifeln zu können glaubte. Aber das tun wir auch heute noch gegenüber dem, was gegenwärtig als «tatsächlich» gilt. Oder meint man, künftige Jahrhunderte werden nicht auch manches von dem, was wir als unzweifelhafte Tatsache hinstellen, in die Rumpelkammer des «blinden» Aberglaubens werfen? Ich bin allerdings überzeugt, daß im menschlichen Tatsachenwissen ein wirklicher Fortschritt stattfindet. Als die «Tatsache», daß die Erde rund ist, einmal entdeckt war, waren alle früheren Vermutungen ins Gebiet des «Aberglaubens» verwiesen. So ist es mit gewissen Wahrheiten der Astronomie, der Wissenschaft vom Leben u. a. Die natürliche Abstammungslehre ist gegenüber allen früheren «Schöpfungshypothesen» ein Fortschritt wie die Erkenntnis, daß die Erde rund ist, gegenüber allen vorhergehenden Vermutungen über deren Gestalt. Dennoch aber bin ich mir klar darüber, daß in unseren gelehrten naturwissenschaftlichen Werken und Abhandlungen manche «Tatsache» steckt, die künftigen Jahrhunderten ebensowenig als Tatsache erscheinen wird, wie uns heute manches, was Agrippa und Paracelsus behaupten. Nicht darauf kommt es an, was sie als «Tatsache» ansahen, sondern darauf, in welchem Geiste sie diese Tatsachen deuteten. - Zu Agrippas Zeiten fand man allerdings mit der von ihm vertretenen «natürlichen Magie», die in der Natur Natürliches - und Geistiges nur im Geiste - suchte, wenig Verständnis; die Menschen hingen an der «übernatürlichen Magie», die im Reiche des Sinnlichen das Geistige suchte, und die Agrippa bekämpfte. Deshalb durfte der Abt Trithem von Sponheim ihm den Rat geben, seine Anschauungen als Geheimlehre nur wenigen Auserlesenen mitzuteilen, die sich zu einer ähnlichen Idee über Natur und Geist aufschwingen können, weil man «auch den Ochsen nur Heu und nicht Zucker wie den Singvögeln gebe». Diesem Abt hat Agrippa vielleicht selbst den richtigen Gesichtspunkt zu danken. Trithemius hat in seiner «Steganographie» ein Werk geschrieben, in dem er mit der verstecktesten Ironie die Vorstellungsart behandelte, welche die Natur mit dem Geiste verwechselt. Er redet in dem Buche scheinbar von lauter übernatürlichen Vorgängen. Wer es liest, so wie es ist, muß glauben, daß der Verfasser von Geisterbeschwörungen, Fliegen von Geistern durch die Luft usw. rede. Läßt man aber gewisse Worte und Buchstaben des Textes unter den Tisch fallen, so bleiben - wie Wolfgang Ernst Heidel im Jahre 1676 nachgewiesen hat - Buchstaben übrig, die, zu Worten zusammengesetzt, rein natürliche Vorgänge darstellen. (Man muß in einem Falle z.B. in einer Beschwörungsformel das erste und letzte Wort ganz weglassen, dann von den übrigen das zweite, vierte, sechste usw. streichen. In den übriggebliebenen Worten muß man wieder den ersten, dritten, fünften usw. Buchstaben streichen. Was dann übrig bleibt, setzt man zu Worten zusammen; und die Beschwörungsformel verwandelt sich in eine rein natürliche Mitteilung.)

[ 4 ] Wie schwer es Agrippa geworden ist, sich selbst aus den Vorurteilen seiner Zeit herauszuarbeiten und zu einer reinen Anschauung emporzuheben, davon liefert den Beweis, daß er seine bereits 1510 verfaßte «Geheime Philosophie» philosophia occulta) nicht vor dem Jahre 1531 erscheinen ließ, weil er sie für unreif hielt. Ferner zeugt davon seine Schrift «Ãœber die Eitelkeit der Wissenschaften» (De vanitate scientiarum), in der er mit Bitterkeit über das wissenschaftliche und sonstige Treiben seiner Zeit redet. Er spricht da ganz deutlich aus, daß er nur schwer sich losgerungen hat von dem Wahn derjenigen, welche in äußerlichen Verrichtungen unmittelbare geistige Vorgänge, in äußerlichen Tatsachen prophetische Hindeutungen auf die Zukunft usw. erblicken. Agrippa schreitet in drei Stufen zum höheren Erkennen fort. Er behandelt als erste Stufe die Welt, wie sie mit ihren Stoffen, ihren physikalischen, chemischen und anderen Kräften den Sinnen gegeben ist. Er nennt die Natur, insofern sie auf dieser Stufe betrachtet wird, die elementarische. Auf der zweiten Stufe betrachtet man die Welt als Ganzes in ihrem natürlichen Zusammenhang, wie sie ihre Dinge nach Maß, Zahl, Gewicht, Harmonie usw. ordnet. Die erste Stufe reiht das nächste an das nächste. Sie sucht die im unmittelbaren Umkreis eines Vorganges liegenden Veranlassungen desselben. Die zweite Stufe betrachtet einen einzelnen Vorgang im Zusammenhange mit dem ganzen Weltall. Sie führt den Gedanken aus, daß jedes Ding unter dem Einfluß aller übrigen Dinge des Weltganzen steht. Vor ihr erscheint dieses Weltganze als eine große Harmonie, in der jedes Einzelne ein Glied ist. Die Welt, unter diesem Gesichtspunkte betrachtet, bezeichnet Agrippa als astrale oder himmlische. Die dritte Stufe des Erkennens ist diejenige, wo der Geist durch die Vertiefung in sich selbst das Geistige, das Urwesen der Welt unmittelbar anschaut. Agrippa spricht da von der geistig-seelischen Welt.

[ 5 ] Die Ansichten, die Agrippa über die Welt und das Verhältnis des Menschen zu ihr entwickelt, treten uns bei Theophrastus Paracelsus in ähnlicher, nur in vollkommenerer Art entgegen. Man betrachtet sie daher besser bei diesem.

[ 6 ] Paracelsus kennzeichnet sich selbst, indem er unter sein Bildnis schreibt: «Eines Andern Knecht soll niemand sein, der für sich selbst kann bleiben allein.» Seine ganze Stellung zur Erkenntnis ist in diesen Worten gegeben. Er will überall auf die Grundlagen des Naturwissens selbst zurückgehen, um durch eigene Kraft zu den höchsten Regionen der Erkenntnis emporzusteigen. Er will als Arzt nicht, wie seine Zeitgenossen, einfach das annehmen, was die damals als Autoritäten geltenden alten Forscher, z. B. Galen oder Avicenna, vor Zeiten behauptet haben; er will selbst unmittelbar im Buche der Natur lesen. «Der Arzt muß durch der Natur Examen gehen, welche die Welt ist; und all ihr Anfang. Und das selbige, was ihm die Natur lehrt, das muß er seiner Weisheit befehlen, aber nichts in seiner Weisheit suchen, sondern allein im Licht der Natur.» Er scheut vor nichts zurück, um die Natur und ihre Wirkungen nach allen Seiten kennenzulernen. Er macht zu diesem Zwecke Reisen nach Schweden, Ungarn, Spanien, Portugal und in den Orient. Er darf von sich sagen: «Ich bin der Kunst nachgegangen mit Gefahr meines Lebens und habe mich nicht geschämt, von Landfahrern, Nachrichtern und Scherern zu lernen. Meine Lehre ward probiert schärfer denn das Silber in Armut, Ängsten, Kriegen und Nöten.» Was von alten Autoritäten überliefert ist, hat für ihn keinen Wert; denn er glaubt nur zu der rechten Anschauung zu kommen, wenn er den Aufstieg von dem Naturwissen zu der höchsten Erkenntnis selbst erlebt. Dieses Selbsterleben legt ihm den stolzen Ausspruch in den Mund: «Wer der Wahrheit nach will, der muß in meine Monarchei... Mir nach; ich nicht euch, Avicenna, Rhases, Galen, Mesur! Mir nach und ich nicht euch, ihr von Paris, ihr von Montpellier, ihr von Schwaben, ihr von Meißen, ihr von Köln, ihr von Wien, und was an der Donau und dem Rheinstrome liegt; ihr Inseln im Meer, du Italien, du Dalmatien, du Athen, du Grieche, du Araber, du Israelite; mir nach und ich nicht euch! Mein ist die Monarchei!» - Man kann Paracelsus wegen seiner rauhen Außenseite, die machmal hinter Scherz tiefen Ernst verbirgt, leicht verkennen. Er sagt doch selbst: «Von der Natur bin ich nicht subtil gesponnen, auch nicht mit Feigen und Weizenbrod, sondern mit Käs, Milch und Haberbtod erzogen, darum bin ich wohl grob gegen die Katzenreinen und Superfeinen; denn dieselben, die in weichen Kleidern, und wir, die in Tannenzapfen erzogen, verstehen einander nicht wohl. Ob ich mir selber holdselig zu sein vermeine, muß ich also für grob gelten. Wie kann ich nicht seltsam sein dem, der nie in der Sonne gewandert hat?»

[ 7 ] Goethe hat das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Natur (in seinem Buche über Winckelmann) mit den schönen Sätzen geschildert: «Wenn die gesunde Natur des Menschen als ein Ganzes wirkt, wenn er sich in der Welt als in einem großen, schönen, würdigen und werten Ganzen fühlt, wenn das harmonische Behagen ihm ein reines, freies Entzücken gewährt: dann würde das Weltall, wenn es sich selbst empfinden könnte, als an sein Ziel gelangt, aufjauchzen, und den Gipfel des eigenen Werdens und Wesens bewundern.» Von einer Empfindung, wie sie sich in solchen Sätzen ausspricht, ist Paracelsus tief durchdrungen. Aus dieser Empfindung heraus gestaltet sich für ihn das Rätsel des Menschen. Sehen wir zu, wie das, im Sinne des Paracelsus, geschieht. Verhüllt ist dem menschlichen Fassungsvermögen zunächst der Weg, den die Natur gegangen ist, um ihren Gipfel hervorzubringen. Sie hat diesen Gipfel erstiegen; aber dieser Gipfel sagt nicht: ich fühle mich als die ganze Natur; dieser Gipfel sagt: ich fühle mich als dieser einzelne Mensch. Was in Wirklichkeit eine Tat der ganzen Welt ist, das fühlt sich als einzelnes, einsames, für sich stehendes Wesen. Ja, das ist gerade das wahre Wesen des Menschen, daß er sich als etwas anderes fühlen muß, als er letzten Endes ist. Und wenn dies ein Widerspruch ist, so darf der Mensch ein lebendig gewordener Widerspruch genannt werden. Der Mensch ist die Welt auf seine eigene Art. Er sieht seinen Einklang mit der Welt als eine Zweiheit an. Er ist dasselbe, was die Welt ist; aber er ist es als Wiederholung, als einzelnes Wesen. Das ist der Gegensatz, den Paracelsus als Mikrokosmos (Mensch) und Makrokosmos (Weltall) empfindet. Der Mensch ist ihm die Welt im Kleinen. Was den Menschen sein Verhältnis zur Welt so ansehen läßt, das ist sein Geist. Dieser Geist erscheint an ein einzelnes Wesen, an einen einzelnen Organismus gebunden. Dieser Organismus gehört, seinem ganzen Wesen nach, dem großen Strom des Weltalls an. Er ist ein Glied in demselben, das nur im Zusammenhange mit allen anderen seinen Bestand hat. Der Geist aber erscheint als ein Ergebnis dieses einzelnen Organismus. Er sieht sich zunächst nur mit diesem Organismus verbunden. Er reißt diesen Organismus aus dem Mutterboden los, dem er entwachsen ist. So liegt für Paracelsus ein tiefer Zusammenhang zwischen dem Menschen und dem ganzen Weltall in der Naturgrundlage des Seins verborgen, der sich durch das Dasein des Geistes verbirgt. Der Geist, der uns zur höheren Erkenntnis flihrt, indem er uns das Wissen vermittelt, und dieses Wissen auf höherer Stufe wieder geboren werden läßt, hat für uns Menschen zunächst die Folge, daß er uns unseren eigenen Zusammenhang mit dem All verhüllt. So löst sich für Paracelsus die menschliche Natur zunächst in drei Glieder auseinander: in unsere sinnlich-körperliche Natur, unseren Organismus, der uns als ein Naturwesen unter anderen Naturwesen erscheint und genau so ist, wie alle anderen Naturwesen; in unsere verhüllte Natur, die ein Glied in der Kette der ganzen Welt ist, die also nicht innerhalb unseres Organismus beschlossen ist, sondern die Kraftwirkungen aussendet und empfängt von dem ganzen Weltall; und in die höchste Natur: unseren Geist, der nur auf geistige Art sich auslebt. Das erste Glied der menschlichen Natur nennt Paracelsus den Elementarleib; das zweite den ätherisch-himmlischen oder astralischen Leib, das dritte Glied nennt er Seele. - In den «astralischen» Erscheinungen sieht also Paracelsus eine Zwischenstufe zwischen den rein körperlichen und den eigentlichen Seelenerscheinungen. Sie werden also dann sichtbar werden, wenn der Geist, welcher die Naturgrundlage unseres Seins verhüllt, seine Tätigkeit einstellt. Die einfachste Erscheinung dieses Gebietes haben wir in der Traumwelt vor uns. Die Bilder, die uns im Traume umgaukeln, mit ihrem merkwürdigen sinnvollen Zusammenhange mit Vorgängen in unserer Umgebung und mit Zuständen unseres eigenen Innern, sind Erzeugnisse unserer Naturgrundlage, die durch das hellere Licht der Seele verdunkelt werden. Wenn ein Stuhl neben meinem Bette umfällt, und ich träume ein ganzes Drama, das mit einem durch ein Duell verursachten Schuß endet, oder wenn ich Herzklopfen habe, und ich träume von einem kochenden Ofen, so kommen Naturwirkungen zum Vorschein, sinnvoll und bedeutsam, die ein Leben enthüllen, das zwischen den rein organischen Funktionen und dem im hellen Bewußtsein des Geistes vollzogenen Vorstellen liegt. An dieses Gebiet schließen sich alle Erscheinungen an, die dem Felde des Hypnotismus und der Suggestion angehören. Wir können in der Suggestion eine Einwirkung von Mensch auf Mensch sehen, die auf einen durch die höhere Geistestätigkeit verhüllten Zusammenhang der Wesen in der Natur deutet. Von hier aus eröffnet sich die Möglichkeit das zu verstehen, was Paracelsus als «astralischen» Leib deutet. Er ist die Summe von Naturwirkungen, unter deren Einfluß wir stehen oder durch besondere Umstände stehen können; die von uns ausgehen, ohne daß unsere Seele dabei in Betracht kommt; und die doch nicht unter den Begriff rein physikalischer Erscheinungen fallen. Daß Paracelsus auf diesem Felde Tatsachen aufzählt, die wir heute bezweifeln, das kommt von einem Gesichtspunkte aus, den ich oben bereits angeführt habe (vgl. S. 103f.), nicht in Betracht. - Auf Grund solcher Anschauungen von der menschlichen Natur sonderte Paracelsus diese in sieben Glieder. Es sind dieselben, welche wir auch in der Weisheit der alten Ägypter, bei den Neuplatonikern und in der Kabbala antreffen. Der Mensch ist zunächst ein physikalisch-körperliches Wesen, also denselben Gesetzen unterworfen, denen jeder Körper unterworfen ist. Er ist also, in dieser Hinsicht, ein rein elementarischer Leib. Die rein körperlich-physikalischen Gesetze gliedern sich zum organischen Lebensprozeß. Paracelsus bezeichnet die organische Gesetzmäßigkeit als «Archaeus» oder «Spiritus vitae»; das Organische erhebt sich zu geistähnlichen Erscheinungen, die noch nicht Geist sind. Es sind dies die «astralischen» Erscheinungen. Aus den «astralischen» Vorgängen tauchen die Funktionen des «tierischen Geistes» auf. Der Mensch ist Sinnenwesen. Er verbindet sinngemäß die sinnlichen Eindrücke durch seinen Verstand. Es belebt sich also in ihm die «Verstandesseele». Er vertieft sich in seine eigenen geistigen Erzeugnisse, er lernt den Geist als Geist erkennen. Er hat sich somit bis zur Stufe der «Geistseele» erhoben. Zuletzt erkennt er, daß er in dieser Geistseele den tiefsten Untergrund des Weltdaseins erlebt; die Geistseele hört auf, eine individuelle, einzelne zu sein. Es tritt die Erkenntnis ein, von der Eckhart sprach, als er nicht mehr sich in sich, sondern das Urwesen in sich sprechen fühlte. Es ist der Zustand eingetreten, in dem der Allgeist im Menschen sich selbst anschaut. Paracelsus hat das Gefühl dieses Zustandes in die einfachen Worte geprägt: «Und das ist ein Großes, das ihr bedenken sollt: nichts ist im Himmel und auf Erden, das nicht sei im Menschen. Und Gott, der im Himmel ist, der ist im Menschen.» - Nichts anderes will Paracelsus mit diesen sieben Grundteilen der menschlichen Natur zum Ausdruck bringen als Tatsachen des äußeren und inneren Erlebens. Daß in höherer Wirklichkeit eine Einheit ist, was sich für die menschliche Erfahrung als Vielheit von sieben Gliedern auseinanderlegt, das bleibt dadurch unangefochten. Aber gerade dazu ist die höhere Erkenntnis da: die Einheit in allem aufzuzeigen, was dem Menschen wegen seiner körperlichen und geistigen Organisation im unmittelbaren Erleben als Vielheit erscheint. Auf der Stufe der höchsten Erkenntnis strebt Paracelsus durchaus darnach, das einheitliche Urwesen der Welt lebendig mit seinem Geiste zu verschmelzen. Er weiß aber, daß der Mensch die Natur in ihrer Geistigkeit nur erkennen kann, wenn er mit ihr in unmittelbaren Verkehr tritt. Nicht dadurch begreift der Mensch die Natur, daß er sie von sich aus mit willkürlich angenommenen geistigen Wesenheiten bevölkert, sondern dadurch, daß er sie hinnimmt und schätzt, so wie sie als Natur ist. Paracelsus sucht daher nicht Gott oder den Geist in der Natur; sondern die Natur, so wie sie ihm vor Augen tritt, ist ihm ganz unmittelbar göttlich. Muß man denn der Pflanze erst eine Seele nach Art der menschlichen Seele beilegen, um das Geistige zu finden? Darum erklärt sich Paracelsus die Entwicklung der Dinge, soweit das mit den wissenschaftlichen Mitteln seiner Zeit möglich ist, durchaus so, daß er diese Entwicklung als einen sinnlichen Naturprozeß auffaßt. Er läßt alle Dinge aus der Urmaterie, dem Urwasser (Yliaster) hervorgehen. Und er betrachtet als einen weiteren Naturprozeß die Scheidung der Urmaterie (die er auch den großen Limbus nennt) in die vier Elemente: Wasser, Erde, Feuer und Luft. Wenn er davon spricht, daß das «göttliche Wort» aus der Urmaterie die Vielheit der Wesen hervorrief, so ist auch das nur so zu verstehen, wie etwa in der neueren Naturwissenschaft das Verhältnis der Kraft zum Stoffe zu verstehen ist. Ein «Geist» im tatsächlichen Sinne ist auf dieser Stufe noch nicht vorhanden. Dieser «Geist» ist kein tatsächlicher Grund des Naturprozesses, sondern ein tatsächliches Ergebnis dieses Prozesses. Dieser Geist schafft nicht die Natur, sondern entwickelt sich aus ihr. Manches Wort des Paracelsus könnte im entgegengesetzten Sinne gedeutet werden. So wenn er sagt: «Es ist nichts körperlich, es hätte und führete nicht auch einen Geist in ihm verborgen und lebete. Es hat auch nicht nur das Leben, was sich regt und bewegt, als die Menschen, die Tiere, die Würmer der Erde, die Vögel im Himmel, und die Fische im Wasser, sondern auch alle körperlichen und wesentlichen Dinge.» Aber mit solchen Aussprüchen will Paracelsus nur vor der oberflächlichen Naturbetrachtung warnen, welche mit ein paar «hingepfahlten» Begriffen (nach Goethes trefflichem Ausdruck) das Wesen eines Dinges auszuschöpfen glaubt. Er will in die Dinge nicht ein ausgedachtes Wesen hineinlegen, sondern alle Kräfte des Menschen in Bewegung setzen, um das, was tatsächlich in dem Dinge liegt, herauszuholen. - Es kommt darauf an, sich dadurch nicht verführen zu lassen, daß Paracelsus sich im Geiste seiner Zeit ausdrückt. Es handelt sich vielmehr darum, zu erkennen, welche Dinge ihm vorschweben, wenn er, auf die Natur blickend, in den Ausdrucksformen seiner Zeit seine Ideen ausdrückt. Er schreibt z.B. dem Menschen ein zweifaches Fleisch, also eine zweifache körperliche Beschaffenheit zu. «Das Fleisch muß also verstanden werden, daß seiner zweierlei Art ist, nämlich das Adam entstammende Fleisch und das Fleisch, welches nicht aus Adam ist. Das Fleisch aus Adam ist ein grobes Fleisch, denn es ist irdisch und sonst nichts als Fleisch, das zu binden und zu fassen ist wie Holz und Stein. Das andere Fleisch ist nicht aus Adam, es ist ein subtiles Fleisch und nicht zu binden oder zu fassen, denn es ist nicht aus Erde gemacht.» Was ist das Fleisch, das aus Adam ist? Es ist alles das, was der Mensch durch seine natürliche Entwicklung überkommen hat, was sich also auf ihn vererbt hat. Dazu kommt das, was sich der Mensch im Verkehr mit der Umwelt im Lauf der Zeiten erworben hat. Die modernen naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen von vererbten und durch Anpassung erworbenen Eigenschaften lösen sich los aus dem angeführten Gedanken des Paracelsus. Das «subtilere Fleisch», das den Menschen zu seinen geistigen Verrichtungen befähigt, ist nicht von Anfang an in dem Menschen gewesen. Er war «grobes Fleisch» wie das Tier, im Fleisch, das «zu binden und zu fassen ist, wie Holz und Stein». Im naturwissenschaftlichen Sinne ist also auch die Seele eine erworbene Eigenschaft des «groben Fleisches». Was der Naturforscher des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts im Auge hat, wenn er von den Erbstücken aus der Tierwelt spricht, das hat Paracelsus im Auge, wenn er das Wort gebraucht, das «aus Adam stammende Fleisch». Durch solche Ausführungen soll natürlich durchaus nicht der Unterschied verwischt werden, der besteht zwischen einem Naturforscher des sechzehnten und einem solchen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts. Erst dieses letztere Jahrhundert war ja imstande, im vollen wissenschaftlichen Sinne die Erscheinungen der Lebewesen in einem solchen Zusammenhange zu sehen, daß deren natürliche Verwandtschaft und tatsächliche Abstammung bis herauf zum Menschen vor Augen trat. Die Naturwissenschaft sieht nur einen Naturprozeß, wo noch Linné im achtzehnten Jahrhundert einen geistigen Prozeß gesehen und mit den Worten charakterisiert hat: «Spezies von Lebewesen zählen so viele, als verschiedene Formen im Prinzip geschaffen worden sind.» Während bei Linné also der Geist noch in die räumliche Welt verlegt werden und ihm die Aufgabe zugewiesen werden muß, die Lebensformen geistig zu erzeugen, zu «schaffen», konnte die Naturwissenschaft des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts der Natur geben, was der Natur ist, und dem Geiste, was des Geistes ist. Der Natur wird selbst die Aufgabe zugewiesen, ihre Schöpfungen zu erklären; und der Geist kann sich dort in sich versenken, wo er allein zu finden ist, im Innern des Menschen. - Aber, wenn Paracelsus auch im gewissen Sinne durchaus im Sinne seiner Zeit denkt, so hat er doch gerade in bezug auf die Idee der Entwickelung, des Werdens, das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Natur in tiefsinniger Weise erfaßt. Er sah in dem Urwesen der Welt nicht etwas, was als Abgeschlossenes irgendwie vorhanden ist, sondern er erfaßte das Göttliche im Werden. Dadurch konnte er dem Menschen wirklich eine selbstschöpferische Tätigkeit zuschreiben. Ist das göttliche Urwesen ein für allemal vorhanden, dann kann von einem wahren Schaffen des Menschen nicht die Rede sein. Nicht der Mensch schafft dann, der in der Zeit lebt, sondern Gott schafft, der von Ewigkeit ist. Aber für Paracelsus ist kein solcher Gott von Ewigkeit. Für ihn ist nur ein ewiges Geschehen, und der Mensch ist ein Glied in diesem ewigen Geschehen. Was der Mensch bildet, war vorher noch in keiner Weise da. Was der Mensch schafft, ist so wie er schafft, eine ursprüngliche Schöpfung. Soll sie göttlich genannt werden, so kann sie so genannt werden nur in dem Sinne, wie sie als menschliche Schöpfung ist. Deshalb kann Paracelsus dem Menschen eine Rolle im Weltenbaue zuweisen, die diesen selbst zum Mitbaumeister an dieser Schöpfung macht. Das göttliche Urwesen ist ohne den Menschen nicht das, was es mit dem Menschen ist. «Denn die Natur bringt nichts an den Tag, was auf seine Statt vollendet sei, sondern der Mensch muß es vollenden.» Diese selbstschöpferische Tätigkeit des Menschen am Bau der Natur nennt Paracelsus Alchymie. «Diese Vollendung ist Alchymie. Also ist der Alchymist der Bäcker, indem er das Brod bäckt, der Rebmann, indem er den Wein macht, der Weber, indem er das Tuch macht.» Paracelsus will auf seinem Gebiet, als Arzt, Alchymist sein. «Darum so mag ich billig in der Alchymie hie so viel schreiben, auf daß ihr sie wohl erkennet, und erfahret, was an ihr sei, und wie sie verstanden soll werden: nicht ein Ärgernis nehmen daran, daß weder Gold noch Silber dir daraus werden soll. Sondern daher betrachtet, daß dir die Arkanen (Heilmittel) eröffnet werden... Die dritte Säule der Medizin ist Alchymie, denn die Bereitung der Arzneien kann ohne sie nicht geschehen, weil die Natur ohne Kunst nicht gebraucht werden kann.»

[ 8 ] Im strengsten Sinne also sind die Augen des Paracelsus auf die Natur gerichtet, um ihr selbst abzulauschen, was sie über ihre Hervorbringungen zu sagen hat. Die chemische Gesetzmäßigkeit will er erforschen, um in seinem Sinne als Alchymist zu wirken. Er denkt sich alle Körper aus drei Grundstoffen zusammengesetzt, aus Salz, Schwefel und Quecksilber. Was er so bezeichnet, deckt sich natürlich nicht mit dem, was die spätere Chemie mit diesem Namen bezeichnet; ebenso wenig wie das, was Paracelsus als Grundstoff auffaßt, ein solcher im Sinne der späteren Chemie ist. Verschiedene Dinge werden zu verschiedenen Zeiten mit denselben Namen bezeichnet. Was die Alten vier Elemente: Erde, Wasser, Luft und Feuer nannten, haben wir noch immer. Wir nennen diese vier «Elemente» nicht mehr «Elemente», sondern Aggregatzustände und haben dafür die Bezeichnungen: fest, flüssig, gasförmig, ätherförmig. Die Erde z. B. war den Alten nicht Erde, sondern das «Feste». Auch die drei Grundstoffe des Paracelsus erkennen wir wohl in gegenwärtigen Begriffen, nicht aber in den gleichlautenden gegenwärtigen Namen wieder. Für Paracelsus sind Auflösung in einer Flüssigkeit und Verbrennung die beiden wichtigen chemischen Prozesse, die er anwendet. Wird ein Körper gelöst oder verbrannt, so zerfällt er in seine Teile. Etwas bleibt als Rückstand; etwas löst sich oder verbrennt. Das Rückständige ist ihm salzartig, das Lösliche (Flüssige) quecksilberartig; das Verbrennliche nennt er schwefelig.

[ 9 ] Wer über solche Naturprozesse nicht hinaussieht, den mögen sie als materiell-nüchterne Dinge kalt lassen; wer den Geist durchaus mit den Sinnen fassen will, der wird diese Prozesse mit allen möglichen Seelenwesen bevölkern. Wer aber, wie Paracelsus, sie im Zusammenhange mit dem All zu betrachten weiß, das im Innern des Menschen sein Geheimnis offenbar werden läßt, der nimmt sie hin, wie sie sich den Sinnen darbieten; er deutet sie nicht erst um; denn so, wie die Naturvorgänge in ihrer sinnlichen Wirklichkeit vor uns stehen, offenbaren sie auf ihre eigene Art das Rätsel des Daseins. Was sie durch diese ihre sinnliche Wirklichkeit aus der Seele des Menschen heraus zu enthüllen haben, steht dem, der nach dem Licht der höheren Erkenntnis strebt, höher als alle übernatürlichen Wunder, die der Mensch ersinnen, oder sich offenbaren lassen mag über ihren angeblichen «Geist». Es gibt keinen «Geist der Natur», der erhabenere Wahrheiten auszusprechen vermöchte, als die großen Werke der Natur selbst, wenn unsere Seele in Freundschaft sich mit dieser Natur verbindet und im vertraulichen Verkehre den Offenbarungen ihrer Geheimnisse lauscht. Solche Freundschaft mit der Natur suchte Paracelsus.

IV. Agrippa of Nettesheim and Theophrastus Paracelsus

[ 1 ] Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1487-1535) and Theophrastus Paracelsus (1493-1541) followed the path indicated by Nicolaus of Cusa's way of thinking. They immersed themselves in nature and sought to explore its laws with all the means available to them in their time, and as comprehensively as possible. In this knowledge of nature they also see the true basis for all higher knowledge. They seek to develop this from natural science itself by allowing it to be reborn in the spirit.

[ 2 ] Agrippa von Nettesheim led a varied life. He came from a noble family and was born in Cologne. He studied medicine and law at an early age and sought to educate himself about natural processes in the way that was customary at the time within certain circles and societies, or even with individual researchers who carefully kept their knowledge of nature secret. He repeatedly went to Paris, Italy and England for such purposes, and also visited the famous Abbot Trithem von Sponheim in Würzburg. He taught at various times in scientific institutions and here and there entered the service of rich and noble people, to whom he put his statesmanlike and scientific skills at their disposal. If his biographers describe the services he rendered as not always impeccable, if it is said that he acquired money by pretending to understand the secret arts and to benefit people through them, this is contrasted with his unmistakable, restless drive to acquire all the knowledge of his time in an honest way and to deepen this knowledge in the sense of a higher understanding of the world. His efforts to gain a clear position on natural science on the one hand and higher knowledge on the other are clearly evident. Such a position can only be attained by those who have an insight into the paths by which one arrives at the one and the other knowledge. As true as it is that natural science must ultimately be lifted up into the region of the spirit if it is to pass over into higher knowledge, it is also true that it must first remain in its own field if it is to provide the right foundation for a higher level. The "spirit in nature" is only there for the spirit. As certainly as nature is spiritual in this sense, so certainly nothing in nature is directly spiritual that is perceived by bodily organs. There is nothing spiritual that can appear to my eye as spiritual. I must not look for the spirit as such in nature. I do this when I interpret a process of the external world directly spiritually, for example when I attribute a soul to the plant that is only remotely analogous to the human soul. I also do this when I attribute a spatial or temporal existence to the spirit or the soul itself, for example when I say of the eternal human soul that it lives on in time without the body, but nevertheless in the manner of a body, instead of as a pure spirit. Or if I even believe that the spirit of a deceased person can show itself in any sensually perceptible events. Spiritism, which commits this error, only shows that it has not penetrated to the true conception of the spirit, but wants to look directly at the spirit in a gross sensuality. It misjudges both the nature of the sensible and that of the spirit. He rejects the ordinary sensual, which takes place before our eyes hour after hour, in order to address something rare, surprising and unusual directly as spirit. He does not understand that what lives as "spirit in nature" reveals itself, for example, when two elastic spheres collide, to those who are able to see spirit; and not only in processes that are astonishing in their rarity and that are not immediately comprehensible in their natural context. But the spiritualist also pulls the spirit down into a lower sphere. Instead of explaining something that takes place in space and that he perceives with his senses through forces and beings that are only spatially and sensually perceptible, he resorts to "spirits", which he thus equates completely with the sensually perceptible. This type of conception is based on a lack of spiritual comprehension. One is not able to look at the spiritual in a spiritual way; therefore one satisfies one's need for the presence of the spirit with mere sensory beings. The spirit shows no spirit to such people; therefore they seek it with the senses. Just as they see clouds flying through the air, they would also like to see spirits rushing along.

[ 3 ] Agrippa von Nettesheim fights for a genuine natural science, which does not want to explain the phenomena of nature through spiritual beings that haunt the sensory world, but which wants to see only the natural in nature and only the spiritual in the mind. - Of course, Agrippa will be completely misunderstood if one compares his natural science with that of later centuries, which has completely different experiences. With such a comparison, it could easily appear that he is still referring to the direct effects of spirits, which is only based on natural connections or false experience. Moritz Carriere does him such an injustice when he says - though not in a malicious sense: "Agrippa gives a large register of things that belong to the sun, the moon, the planets or fixed stars and receive influences from them; e.g. fire, blood, laurel, gold, chrysolite are related to the sun; they bestow the gift of the sun: courage, cheerfulness, light... Animals have a sense of nature that approaches the spirit of prophecy more sublimely than the human mind... People can be bound to love and hate, to sickness and health. Thus thieves are bound so that they cannot steal anywhere, merchants so that they cannot trade, ships and mills so that they cannot go, lightning so that they cannot strike. It is done by potions, ointments, images, rings, enchantments; the blood of hyenas or basilisks is suitable for such use - it is reminiscent of Shakespeare's witches' cauldron." No, it is not reminiscent of that, if you understand Agrippa correctly. He naturally believed in facts that people in his time thought they could not doubt. But we still do today in the face of what is currently considered "factual". Or do we think that future centuries will not throw some of what we present as undoubted fact into the dustbin of "blind" superstition? I am, however, convinced that real progress is being made in human knowledge of facts. Once the "fact" that the earth is round was discovered, all previous assumptions were relegated to the realm of "superstition". So it is with certain truths of astronomy, the science of life, etc. The doctrine of natural descent is an advance on all earlier "creation hypotheses", just as the realization that the earth is round is an advance on all previous assumptions about its shape. Nevertheless, I am aware that our learned scientific works and treatises contain many a "fact" that will appear to future centuries to be just as little a fact as some of what Agrippa and Paracelsus claim today. What matters is not what they regarded as "fact", but the spirit in which they interpreted these facts. - In Agrippa's time, however, there was little understanding for the "natural magic" he advocated, which sought the natural in nature - and the spiritual only in the mind; people were attached to "supernatural magic", which sought the spiritual in the realm of the sensual, and which Agrippa fought against. For this reason, Abbot Trithem of Sponheim was allowed to advise him to communicate his views as a secret doctrine only to a select few, who could rise to a similar idea about nature and spirit, because "even the oxen are only given hay and not sugar like the songbirds". Agrippa himself perhaps has this abbot to thank for the correct point of view. In his "Steganography", Trithemius wrote a work in which he treated with the most hidden irony the way of thinking that confuses nature with the spirit. In the book he seems to speak of nothing but supernatural processes. Anyone who reads it as it stands must believe that the author is talking about conjuring spirits, spirits flying through the air, etc. If, however, certain words and letters of the text are ignored, then - as Wolfgang Ernst Heidel proved in 1676 - letters remain which, when put together to form words, represent purely natural processes. (In one case, for example, the first and last word of an incantation must be omitted entirely, then the second, fourth, sixth, etc. of the remaining words must be deleted. In the remaining words one must again delete the first, third, fifth, etc. letters. What then remains is put together to form words; and the incantation is transformed into a purely natural message.)

[ 4 ] The difficulty Agrippa had in working himself out of the prejudices of his time and elevating himself to a pure view is demonstrated by the fact that he did not allow his "Secret Philosophy" (philosophia occulta), written as early as 1510, to appear before 1531 because he considered it immature. Furthermore, his writing "On the Vanity of the Sciences" (De vanitate scientiarum), in which he speaks with bitterness about the scientific and other activities of his time, bears witness to this. He states quite clearly that he has had great difficulty in freeing himself from the delusion of those who see immediate spiritual processes in external activities, prophetic indications of the future in external facts, and so on. Agrippa progresses to higher knowledge in three stages. As the first stage, he treats the world as it is given to the senses with its substances, its physical, chemical and other forces. He calls nature, insofar as it is considered at this level, elementary. At the second level, the world is considered as a whole in its natural context, as it organizes its things according to measure, number, weight, harmony, etc. The first stage arranges one thing after another. It looks for the causes of a process in its immediate surroundings. The second stage considers a single process in connection with the whole universe. It develops the idea that each thing is under the influence of all other things in the world as a whole. Before it, this whole of the world appears as a great harmony in which each individual is a member. Agrippa describes the world from this point of view as astral or celestial. The third stage of cognition is that in which the spirit, by deepening into itself, directly beholds the spiritual, the primordial being of the world. Agrippa speaks here of the spiritual-soul world.

[ 5 ] The views that Agrippa develops about the world and man's relationship to it are found in Theophrastus Paracelsus in a similar, only more perfect way. It is therefore better to consider them with him.

[ 6 ] Paracelsus characterizes himself by writing below his portrait: "No one should be the servant of another who can remain alone for himself." His entire position on knowledge is given in these words. He wants to go back everywhere to the foundations of natural knowledge itself in order to ascend to the highest regions of knowledge through his own strength. As a physician, he does not want, like his contemporaries, to simply accept what the old researchers, e.g. Galen or Avicenna, who were regarded as authorities at the time, had claimed in the past; he wants to read directly in the Book of Nature himself. "The physician must go through the examinations of nature, which is the world and all its beginnings. And that which nature teaches him, he must command to his wisdom, but seek nothing in his wisdom, but only in the light of nature." He spares nothing to get to know nature and its effects from all sides. To this end, he traveled to Sweden, Hungary, Spain, Portugal and the Orient. He can say of himself: "I have pursued the art at the risk of my life and have not been ashamed to learn from overland travelers, teachers and shepherds. My teaching was tried sharper than silver in poverty, fears, wars and hardships." What has been handed down by old authorities has no value for him; for he believes that he can only arrive at the right view if he experiences the ascent from natural knowledge to the highest knowledge himself. This self-experience puts the proud saying into his mouth: "Whoever wants to follow the truth must enter my monarchy... Follow me; I do not follow you, Avicenna, Rhases, Galen, Mesur! After me and not you, you of Paris, you of Montpellier, you of Swabia, you of Meissen, you of Cologne, you of Vienna, and what lies along the Danube and the Rhine; you islands in the sea, you Italy, you Dalmatia, you Athens, you Greek, you Arab, you Israelite; after me and not you! Mine is the monarchy!" - It is easy to misjudge Paracelsus because of his rough exterior, which sometimes hides deep seriousness behind jesting. He himself says: "I was not subtly spun by nature, nor was I brought up with figs and wheat bread, but with cheese, milk and honeydew, which is why I am probably rough on the feline and the superfine; for those who are brought up in soft clothes and we who are brought up in pine cones do not understand each other well. So even if I think I am kind to myself, I must be considered rude. How can I not be strange to one who has never walked in the sun?"