The Science of Knowing

GA 2

X. The Inner Nature of Thinking

[ 1 ] Let us take another step toward thinking. Until this point we have merely looked at the position thinking takes toward the rest of the world of experience. We have arrived at the view that it holds a very privileged position within this world, that it plays a central role. Let us disregard that now. Let us limit ourselves here to the inner nature of thinking. Let us investigate the thought-world's very own character, in order to experience how one thought depends upon the other and how the thoughts relate to each other. Only by this means will we first be able to gain enlightenment about the question: What is knowing activity? Or, in other words: What does it mean to make thoughts for oneself about reality; what does it mean to want to come to terms with the world through thinking?

[ 2 ] We must keep ourselves free of any preconceived notions. It would be just such a preconception, however, if we were to presuppose that the concept (thought) is a picture, within our consciousness, by which we gain enlightenment about an object lying outside our consciousness. We are not concerned here with this and similar presuppositions. We take thoughts as we find them. Whether they have a relationship to something else or other, and what this relationship might be, is precisely what we want to investigate. We should not therefore place these questions here as a starting point. Precisely the view indicated, about the relationship of concept and object, is a very common one. One often defines the concept, in fact, as the spiritual image of things, providing us with a faithful photograph of them. When one speaks of thinking, one often thinks only of this presupposed relationship. One scarcely ever seeks to travel through the realm of thoughts, for once, within its own region, in order to see what one might find there.

[ 3 ] Let us investigate this realm as though there were nothing else at all outside its boundaries, as though thinking were all of reality. For a time we will disregard all the rest of the world.

[ 4 ] The fact that one has failed to do this in the epistemological studies basing themselves on Kant has been disastrous for science. This failure has given a thrust to this science in a direction utterly antithetical to our own. By its whole nature, this trend in science can never understand Goethe. It is in the truest sense of the word un-Goethean for a person to take his start from a doctrine that he does not find in observation but that he himself inserts into what is observed. This occurs, however, if one places at the forefront of science the view that between thinking and reality, between idea and world, there exists the relationship just indicated. One acts as Goethe would only if one enters deeply into thinking's own nature itself and then observes the relationship that results when this thinking, known in its own being, is then brought into connection with experience.

[ 5 ] Goethe everywhere takes the route of experience in the strictest sense. He first of all takes the objects as they are and seeks, while keeping all subjective opinions completely at a distance, to penetrate their nature; he then sets up the conditions under which the objects can enter into mutual interaction and waits to see what will result. Goethe seeks to give nature the opportunity, in particularly characteristic situations that he establishes, to bring its lawfulness into play, to express its laws itself, as it were.

[ 6 ] How does our thinking manifest to us when looked at for itself? It is a multiplicity of thoughts woven together and organically connected in the most manifold ways. But when we have sufficiently penetrated this multiplicity from all directions, it simply constitutes a unity again, a harmony. All its parts relate to each other, are there for each other; one part modifies the other, restricts it, and so on. As soon as our spirit pictures two corresponding thoughts to itself, it notices at once that they actually flow together into one. Everywhere in our spirit's thought-realm it finds elements that belong together; this concept joins itself to that one, a third one elucidates or supports a fourth, and so on. Thus, for example, we find in our consciousness the thought-content “organism”; when we scan our world of mental pictures, we hit upon a second thought-content: “lawful development, growth.” It becomes clear to us at once that both these thought-contents belong together, that they merely represent two sides of one and the same thing. But this is how it is with our whole system of thoughts. All individual thoughts are parts of a great whole that we call our world of concepts.

[ 7 ] If any single thought appears in my consciousness, I am not satisfied until it has been brought into harmony with the rest of my thinking. A separate concept like this, set off from the rest of my spiritual world, is altogether unbearable to me. I am indeed conscious of the fact that there exists an inwardly established harmony between all thoughts, that the world of thoughts is a unified one. Therefore every such isolation is unnatural, untrue.

[ 8] If we have struggled through to where our whole thought-world bears a character of complete inner harmony, then through it the contentment our spirit demands becomes ours. Then we feel ourselves to be in possession of the truth.

[ 9 ] As a result of our seeing truth to be the thorough-going harmony of all the concepts we have at our command, the question forces itself upon us: Yes, but does thinking even have any content if you disregard all visible reality, if you disregard the sense-perceptible world of phenomena? Does there not remain a total void, a pure phantasm, if we think away all sense-perceptible content?

[ 10 ] That this is indeed the case could very well be a widespread opinion, so we must look at it a little more closely. As we have already noted above, many people think of the entire system of concepts as in fact only a photograph of the outer world. They do indeed hold onto the fact that our knowing develops in the form of thinking, but demand nevertheless that a “strictly objective science” take its content only from outside. According to them the outer world must provide the substance that flows into our concepts. Without the outer world, they maintain, these concepts are only empty schemata without any content. If this outer world fell away, concepts and ideas would no longer have any meaning, for they are there for the sake of the outer world. One could call this view the negation of the concept. For then the concept no longer has any significance at all for the objective world. It is something added onto the latter. The world would stand there in all its completeness even if there were no concepts. For they in fact bring nothing new to the world. They contain nothing that would not be there without them. They are there only because the knowing subject wants to make use of them in order to have, in a form appropriate to this subject, that which is otherwise already there. For this subject, they are only mediators of a content that is of a non-conceptual nature. This is the view presented.

[ 11 ] If it were justified, one of the following three presuppositions would have to be correct.

[ 12 ] 1. The world of concepts stands in a relationship to the outer world such that it only reproduces the entire content of this world in a different form. Here “outer world” means the sense world. If that were the case, one truly could not see why it would be necessary to lift oneself above the sense world at all. The entire whys and wherefores of knowing would after all already be given along with the sense world.

[ 13 ] 2. The world of concepts takes up, as its content, only a part of “what manifests to the senses.” Picture the matter something like this. We make a series of observations. We meet there with the most varied objects. In doing so we notice that certain characteristics we discover in an object have already been observed by us before. Our eye scans a series of objects \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), \(D\), etc. \(A\) has the characteristics \(p\), \(q\), \(a\), \(r\); \(B\): \(l\), \(m\), \(b\), \(n\); \(C\): \(k\), \(h\), \(c\), \(g\); and \(D\): \(p\), \(u\), \(a\), \(v\). In \(D\) we again meet the characteristics \(a\) and \(p\), which we have already encountered in \(A\). We designate these characteristics as essential. And insofar as \(A\) and \(D\) have the same essential characteristics, we say that they are of the same kind. Thus we bring \(A\) and \(D\) together by holding fast to their essential characteristics in thinking. There we have a thinking that does not entirely coincide with the sense world, a thinking that therefore cannot be accused of being superfluous as in the case of the first presupposition above; nevertheless it is still just as far from bringing anything new to the sense world. But one can certainly raise the objection to this that, in order to recognize which characteristics of a thing are essential, there must already be a certain norm making it possible to distinguish the essential from the inessential. This norm cannot lie in the object, for the object in fact contains both what is essential and inessential in undivided unity. Therefore this norm must after all be thinking's very own content.

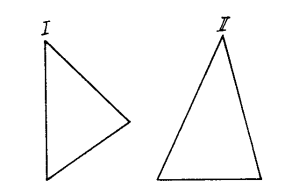

[ 14 ] This objection, however, does not yet entirely overturn this view. One can say, namely, that it is an unjustified assumption to declare that this or that is more essential or less essential for a thing. We are also not concerned about this. It is merely a matter of our encountering certain characteristics that are the same in several things and of our then stating that these things are of the same kind. It is not at all a question of whether these characteristics, which are the same, are also essential. But this view presupposes something that absolutely does not fit the facts. Two things of the same kind really have nothing at all in common if a person remains only with sense experience. An example will make this clear. The simplest example is the best, because it is the most surveyable. Let us look at the following two triangles.

[ 15 ] What is really the same about them if we remain with sense experience? Nothing at all. What they have in common—namely, the law by which they are formed and which brings it about that both fall under the concept “triangle”—we can gain only when we go beyond sense experience. The concept “triangle” comprises all triangles. We do not arrive at it merely by looking at all the individual triangles. This concept always remains the same for me no matter how often I might picture it, whereas I will hardly ever view the same “triangle” twice. What makes an individual triangle into “this” particular one and no other has nothing whatsoever to do with the concept. A particular triangle is this particular one not through the fact that it corresponds to that concept but rather because of elements lying entirely outside the concept: the length of its sides, size of its angles, position, etc. But it is after all entirely inadmissible to maintain that the content of the concept “triangle” is drawn from the objective sense world, when one sees that its content is not contained at all in any sense-perceptible phenomenon.

[ 16 ] 3. Now there is yet a third possibility. The concept could in fact be the mediator for grasping entities that are not sense-perceptible but that still have a self-sustaining character. This latter would then be the non-conceptual content of the conceptual form of our thinking. Anyone who assumes such entities, existing beyond experience, and credits us with the possibility of knowing about them must then also necessarily see the concept as the interpreter of this knowing.

[ 17 ] We will demonstrate the inadequacy of this view more specifically later. Here we want only to note that it does not in any case speak against the fact that the world of concepts has content. For, if the objects about which one thinks lie beyond any experience and beyond thinking, then thinking would all the more have to have within itself the content upon which it finds its support. It could not, after all, think about objects for which no trace is to be found within the world of thoughts.

[ 18 ] It is in any case clear, therefore, that thinking is not an empty vessel; rather, taken purely for itself, it is full of content; and its content does not coincide with that of any other form of manifestation.

10. Innere Natur des Denkens

[ 1 ] Wir treten dem Denken noch um einen Schritt näher. Bisher haben wir bloß die Stellung desselben zu der übrigen Erfahrungswelt betrachtet. Wir sind zu der Ansicht gekommen, daß es innerhalb derselben eine ganz bevorzugte Stellung einnimmt, daß es eine zentrale Rolle spielt. Davon wollen wir jetzt absehen. Wir wollen uns hier nur auf die innere Natur des Denkens beschränken. Wir wollen den selbsteigenen Charakter der Gedankenwelt untersuchen, um zu erfahren, wie ein Gedanke von dem andern abhängt; wie d je Gedanken zueinander stehen. Daraus erst werden sich uns die Mittel ergeben, Aufschluß über die Frage zu gewinnen: Was ist überhaupt Erkennen? Oder mit anderen Worten: Was heißt es, sich Gedanken über die Wirklichkeit zu machen; was heißt es, sich durch Denken mit der Welt auseinandersetzen zu wollen?

[ 2 ] Wir müssen uns da von jeder vorgefaßten Meinung frei erhalten. Eine solche aber wäre es, wenn wir voraussetzen wollten, der Begriff (Gedanke) sei das Bild innerhalb unseres Bewußtseins, durch das wir Aufschluß über einen außerhalb desselben liegenden Gegenstand gewinnen. Von dieser und ähnlichen Voraussetzungen ist an diesem Orte nicht die Rede. Wir nehmen die Gedanken, wie wir sie vorfinden. Ob sie zu irgend etwas anderem eine Beziehung haben und was für eine, das wollen wir eben untersuchen. Wir dürfen es daher nicht hier als Ausgangspunkt hinstellen. Gerade die angedeutete Ansicht über das Verhältnis von Begriff und Gegenstand ist sehr häufig. Man definiert ja oft den Begriff als das geistige Gegenbild eines außerhalb des Geistes liegenden Gegenstandes. Die Begriffe sollen die Dinge abbilden, uns eine getreue Photographie derselben vermitteln. Man denkt oft, wenn man vom Denken spricht, überhaupt nur an dieses vorausgesetzte Verhältnis. Fast nie trachtet man danach, das Reich der Gedanken innerhalb seines eigenen Gebietes einmal zu durchwandern, um zu sehen, was sich hier ergibt.

[ 3 ] Wir wollen dieses Reich hier in der Weise untersuchen, als ob es außerhalb der Grenzen desselben überhaupt nichts mehr gäbe, als ob das Denken alle Wirklichkeit wäre. Wir sehen für einige Zeit von der ganzen übrigen Welt ab.

[ 4 ] Daß man das in den erkenntnistheoretischen Versuchen, die sich auf Kant stützen, unterlassen hat, ist verhängnisvoll für die Wissenschaft geworden. Diese Unterlassung hat den Anstoß zu einer Richtung in dieser Wissenschaft gegeben, die der unsrigen völlig entgegengesetzt ist. Diese Wissenschaftsrichtung kann ihrer ganzen Natur nach Goethe nie begreifen. Es ist im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes ungoethisch, von einer Behauptung auszugehen, die man nicht in der Beobachtung vorfindet, sondern selbst in das Beobachtete hineinlegt. Das geschieht aber, wenn man die Ansicht an die Spitze der Wissenschaft stellt: Zwischen Denken und Wirklichkeit, Idee und Welt besteht das angedeutete Verhältnis. Im Sinne Goethes handelt man nur, wenn man sich in die eigene Natur des Denkens selbst vertieft und dann zusieht, welche Beziehung sich ergibt, wenn dann dieses seiner Wesenheit nach erkannte Denken zu der Erfahrung in ein Verhältnis gebracht wird.

[ 5 ] Goethe geht überall den Weg der Erfahrung im strengsten Sinne. Er nimmt zuerst die Objekte, wie sie sind, sucht mit völliger Fernhaltung aller subjektiven Meinung ihre Natur zu durchdringen; dann stellt er die Bedingungen her, unter denen die Objekte in Wechselwirkung treten können und wartet ab, was sich hieraus ergibt. Goethe sucht der Natur Gelegenheit zu geben, ihre Gesetzmäßigkeit unter besonders charakteristischen Umständen, die er herbeiführt, zur Geltung zu bringen, gleichsam ihre Gesetze selbst auszusprechen.

[ 6 ] Wie erscheint uns unser Denken für sich betrachtet? Es ist eine Vielheit von Gedanken, die in der mannigfachsten Weise miteinander verwoben und organisch verbunden sind. Diese Vielheit macht aber, wenn wir sie nach allen Seiten hinreichend durchdrungen haben, doch wieder nur eine Einheit, eine Harmonie aus. Alle Glieder haben Bezug aufeinander, sie sind füreinander da; das eine modifiziert das andere, schränkt es ein und so weiter. Sobald sich unser Geist zwei entsprechende Gedanken vorstellt, merkt er alsogleich, daß sie eigentlich in eins miteinander verfließen. Er findet überall Zusammengehöriges in seinem Gedankenbereiche; dieser Begriff schließt sich an jenen, ein dritter erläutert oder stützt einen vierten und so fort. So zum Beispiel finden wir in unserm Bewußtsein den Gedankeninhalt «Organismus» vor; durchmustern wir unsere Vorstellungswelt, so treffen wir auf einen zweiten: «gesetzmäßige Entwicklung, Wachstum». Sogleich wird klar, daß diese beiden Gedankeninhalte zusammengehören, daß sie bloß zwei Seiten eines und desselben Dinges vorstellen. So aber ist es mit unserm ganzen Gedankensystem. Alle Einzelgedanken sind Teile eines großen Ganzen, das wir unsere Begriffswelt nennen.

[ 7 ] Tritt irgendein einzelner Gedanke im Bewußtsein auf, so ruhe ich nicht eher, bis er mit meinem übrigen Denken in Einklang gebracht ist. Ein solcher Sonderbegriff, abseits von meiner übrigen geistigen Welt, ist mir ganz und gar unerträglich. Ich bin mir eben dessen bewußt, daß eine innerlich begründete Harmonie aller Gedanken besteht, daß die Gedankenwelt eine einheitliche ist. Deshalb ist uns jede solche Absonderung eine Unnatürlichkeit, eine Unwahrheit.

[ 8 ] Haben wir uns bis dahin durchgerungen, daß unsere ganze Gedankenwelt den Charakter einer vollkommenen, inneren Übereinstimmung trägt, dann wird uns durch sie jene Befriedigung, nach der unser Geist verlangt. Dann fühlen wir uns im Besitze der Wahrheit.

[ 9 ] Indem wir die Wahrheit in der durchgängigen Zusammenstimmung aller Begriffe, über die wir verfügen, sehen, drängt sich die Frage auf: Ja, hat denn das Denken, abgesehen von aller anschaulichen Wirklichkeit, von der sinnenfälligen Erscheinungswelt, auch einen Inhalt? Bleibt nicht die vollständige Leere, ein reines Phantasma zurück, wenn wir allen sinnlichen Inhalt beseitigt denken?

[ 10 ] Daß das letztere der Fall sei, dürfte wohl eine weit verbreitete Meinung sein, so daß wir sie ein wenig näher betrachten müssen. Wie wir bereits oben bemerkten, denkt man sich ja so vielfach das ganze Begriffssystem nur als eine Photographie der Außenwelt. Man hält zwar daran fest, daß sich unser Wissen in der Form des Denkens entwickelt; fordert aber von einer «streng objektiven Wissenschaft», daß sie ihren Inhalt nur von außen nehme. Die Außenwelt müsse den Stoff liefern, welcher in unsere Begriffe einfließt.9J. H. von Kirchmann sagt sogar in seiner «Lehre vom Wissen [als Einleitung in das Studium philosophischer Werke]» (Leipzig 1873, 3 verbesserte Auflage), daß das Erkennen ein Einfließen der Außenwelt in unser Bewußtsein sei. Ohne jene seien diese leere Schemen ohne allen Inhalt. Fiele die Außenwelt weg, so hätten Begriffe und Ideen keinen Sinn mehr, denn sie sind um ihrer willen da. Man könnte diese Ansicht die Verneinung des Begriffs nennen. Denn er hat für die Objektivität dann gar keine Bedeutung mehr. Er ist ein zu letzterer Hinzugekommenes. Die Welt stünde in aller Vollkommenheit auch da, wenn es keine Begriffe gäbe. Denn sie bringen ja nichts Neues zu derselben hinzu. Sie enthalten nichts, was ohne sie nicht da wäre. Sie sind nur da, weil sich das erkennende Subjekt ihrer bedienen will, um in einer ihm angemessenen Form das zu haben, was anderweitig schon da ist. Sie sind für dasselbe nur Vermittler eines Inhaltes, der nichtbegrifflicher Natur ist. So die angezogene Ansicht.

[ 11 ] Wenn sie begründet wäre, müßte eine von den folgenden drei Voraussetzungen richtig sein.

[ 12 ] 1. Die Begriffswelt stehe in einem solchen Verhältnisse zur Außenwelt, daß sie nur den ganzen Inhalt derselben in anderer Form wiedergibt. Hier ist unter Außenwelt die Sinnenwelt verstanden. Wenn das der Fall wäre, dann könnte man wahrlich nicht einsehen, welche Notwendigkeit bestände, sich überhaupt über die Sinnenwelt zu erheben. Man hat ja das ganze Um und Auf des Erkennens schon mit der letzteren gegeben.

[ 13 ] 2. Die Begriffswelt nehme nur einen Teil der «Erscheinung für die Sinne» als ihren Inhalt auf. Man denke sich die Sache etwa so. Wir machen eine Reihe von Beobachtungen. Wir treffen da auf die verschiedensten Objekte. Wir bemerken dabei, daß gewisse Merkmale, die wir an einem Gegenstande entdecken, schon einmal von uns beobachtet worden sind. Es durchmustere unser Auge eine Reihe von Gegenständen A, B, C, D usw. A hätte die Merkmale q a r; B: 1mb n; C: k h cg und D:p na v. Da treffen wir bei D wieder auf die Merkmale a und p, die wir schon bei A angetroffen haben. Wir bezeichnen diese Merkmale als wesentliche. Und insoferne A und D die wesentlichen Merkmale gleich haben, nennen wir sie gleichartig. So fassen wir A und D dann zusammen, indem wir ihre wesentlichen Merkmale im Denken festhalten. Da haben wir ein Denken, das sich mit der Sinnenwelt nicht ganz deckt, auf das also die oben gerügte Überflüssigkeit nicht anzuwenden und das doch ebenso weit entfernt ist, Neues zu der Sinnenwelt hinzuzubringen. Dagegen läßt sich vor allem sagen: um zu erkennen, welche Eigenschaften einem Dinge wesentlich sind, dazu gehöre schon eine gewisse Norm, die es uns möglich macht, Wesentliches von Unwesentlichem zu unterscheiden. Diese Norm kann in dem Objekte nicht liegen, denn dieses enthält ja das Wesentliche und Unwesentliche in ungetrennter Einheit. Diese Norm müsse also doch selbsteigener Inhalt unseres Denkens sein.

[ 14 ] Dieser Einwand stößt aber die Ansicht noch nicht ganz um. Man kann nämlich sagen: Das sei eben eine ungerecht-fertigte Annahme, daß dies oder jenes wesentlicher oder unwesentlicher für ein Ding sei. Das kümmere uns auch nicht. Es handle sich bloß darum, daß wir gewisse gleiche Eigenschaften bei mehreren Dingen antreffen, und die letzteren nennen wir dann gleichartig. Davon sei gar nicht die Rede, daß diese gleichen Eigenschaften auch wesentlich seien. Diese Anschauung setzt aber etwas voraus, was durchaus nicht zutrifft. Es ist in zwei Dingen gleicher Gattung gar nichts wirklich Gemeinschaftliches, wenn man bei der Sinnenerfahrung stehen bleibt. Ein Beispiel wird das klarlegen. Das einfachste ist das beste, weil es sich am besten überschauen läßt. Betrachten wir folgende zwei Dreiecke.

[ 15 ] Was haben die wirklich gleich, wenn man bei der Sinnenerfahrung stehen bleibt? Gar nichts. Was sie gleich haben, nämlich das Gesetz, nach dem sie gebildet sind und welches bewirkt, daß sie beide unter den Begriff «Dreieck» fallen, das wird von uns erst gewonnen, wenn wir die Sinnenerfahrung überschreiten. Der Begriff «Dreieck» umfaßt alle Dreiecke. Wir kommen nicht durch die bloße Betrachtung aller einzelnen Dreiecke zu ihm. Dieser Begriff bleibt immer derselbe, so oft ich ihn auch vorstellen mag, während es mir wohl kaum gelingen wird, zweimal dasselbe «Dreieck» anzuschauen. Das, wodurch das Einzeldreieck das vollbestimmte «dieses» und kein anderes ist, hat mit dem Begriffe gar nichts zu tun. Ein bestimmtes Dreieck ist dieses bestimmte nicht dadurch, daß es jenem Begriffe entspricht, sondern durch Elemente, die ganz außerhalb des Begriffes liegen: Länge der Seiten, Größe der Winkel, Lage usw. Es ist aber doch ganz unstatthaft zu behaupten, daß der Inhalt des Begriffes «Dreieck» aus der objektiven Sinnenwelt entlehnt sei, wenn man sieht, daß dieser sein Inhalt überhaupt in keiner sinnenfälligen Erscheinung enthalten ist.

[ 16 ] 3. Es ist nun noch ein Drittes möglich. Der Begriff könnte ja der Vermittler für das Erfassen von Wesenheiten sein, die nicht sinnlichwahrnehmbar sind, die aber doch einen auf sich selbst beruhenden Charakter haben. Der letztere wäre dann der unbegriffliche Inhalt der begrifflichen Form unseres Denkens. Wer solche jenseits der Erfahrung bestehende Wesenheiten annimmt und uns die Möglichkeit eines Wissens von denselben zuspricht, muß doch notwendig auch in dem Begriffe den Dolmetsch dieses Wissens sehen.

[ 17 ] Wir werden das Unzulängliche dieser Ansicht noch besonders darlegen. Hier wollen wir nur darauf aufmerksam machen, daß sie jedenfalls nicht gegen die Inhaltlichkeit der Begriffswelt spricht. Denn lägen die Gegenstände, über die gedacht wird, jenseits aller Erfahrung und jenseits des Denkens, dann müßte das letztere doch um so mehr innerhalb seiner selbst den Inhalt haben, auf den es sich stützt. Es könnte doch nicht über Gegenstände denken, von denen innerhalb der Gedankenwelt keine Spur anzutreffen wäre.

[ 18 ] Jedenfalls ist also klar, daß das Denken kein inhaltsleeres Gefäß ist, sondern daß es rein für sich selbst genommen inhaltsvoll ist und daß sich sein Inhalt nicht mit dem einer andern Erscheinungsform deckt.

10. inner nature of thinking

[ 1 ] We are taking another step closer to thinking. So far we have only considered its position in relation to the rest of the world of experience. We have come to the conclusion that it occupies a very privileged position within it, that it plays a central role. We will refrain from this now. We shall confine ourselves here only to the internal nature of thought. We want to examine the self-inherent character of the world of thought in order to find out how one thought depends on the other ; how thoughts relate to each other. Only this will give us the means to gain insight into the question: What is knowledge at all? Or in other words: What does it mean to think about reality; what does it mean to want to come to terms with the world through thinking?

[ 2 ] We must keep ourselves free of any preconceived opinion. But it would be such an opinion if we wanted to presuppose that the concept (thought) is the image within our consciousness, through which we gain information about an object lying outside it. This and similar presuppositions are not discussed here. We take the thoughts as we find them. Whether they have a relation to anything else, and what kind of relation, is what we want to investigate. We must therefore not take it here as a starting point. The above-mentioned view of the relationship between concept and object is very common. The concept is often defined as the mental counter-image of an object lying outside the mind. Concepts are supposed to depict things, to give us a faithful photograph of them. When one speaks of thinking, one often thinks only of this presupposed relationship. One almost never seeks to wander through the realm of thought within one's own area in order to see what arises here.

[ 3 ] We want to examine this realm here as if there were nothing at all outside its boundaries, as if thought were all reality. We look away from the rest of the world for a while.

[ 4 ] The fact that this has been omitted in the epistemological attempts based on Kant has been disastrous for science. This omission has given the impetus to a direction in this science that is completely opposed to ours. By its very nature, this direction of science can never comprehend Goethe. It is in the truest sense of the word unGoethean to proceed from an assertion which one does not find in observation, but which one places in what is observed. But this is what happens when you place the view at the forefront of science: The indicated relationship exists between thought and reality, idea and world. One only acts in Goethe's sense if one immerses oneself in the nature of thinking itself and then observes what relationship arises when this thinking recognized according to its essence is brought into a relationship with experience.

[ 5 ] Goethe follows the path of experience in the strictest sense everywhere. He first takes the objects as they are, seeks to penetrate their nature with complete detachment from all subjective opinion; then he establishes the conditions under which the objects can interact and waits to see what results from this. Goethe seeks to give nature the opportunity to bring its laws to bear under particularly characteristic circumstances, which he brings about, to express its laws himself, as it were.

[ 6 ] How does our thinking appear to us when viewed by itself? It is a multitude of thoughts that are interwoven and organically connected in the most diverse ways. But this multiplicity, once we have penetrated it sufficiently on all sides, only constitutes a unity, a harmony. All the links relate to each other, they are there for each other; one modifies the other, restricts it and so on. As soon as our mind imagines two corresponding thoughts, it immediately realizes that they actually merge into one. It finds everywhere what belongs together in its realm of thought; this concept joins that, a third explains or supports a fourth, and so on. Thus, for example, we find in our consciousness the thought content "organism"; if we look through our imaginary world, we encounter a second one: "lawful development, growth". It immediately becomes clear that these two thought contents belong together, that they merely represent two sides of one and the same thing. But so it is with our whole system of thought. All individual thoughts are parts of a large whole that we call our conceptual world.

[ 7 ] If any individual thought appears in my consciousness, I do not rest until it has been harmonized with the rest of my thinking. Such a special concept, apart from the rest of my spiritual world, is completely intolerable to me. I am aware of the fact that there is an inner harmony of all thoughts, that the world of thought is a unified one. Therefore, any such separation is an unnaturalness, an untruth.

[ 8 ] Once we have come to the conclusion that our entire world of thought has the character of a perfect, inner harmony, then it will give us the satisfaction that our spirit longs for. Then we feel that we are in possession of the truth.

[ 9 ] Since we see truth in the consistent coherence of all the concepts at our disposal, the question arises: Yes, does thinking, apart from all vivid reality, from the sensory world of appearances, also have a content? Doesn't complete emptiness, a pure phantasm, remain when we think all sensory content has been eliminated?

[ 10 ] That the latter is the case is probably a widespread opinion, so that we must take a closer look at it. As we have already noted above, the whole conceptual system is often thought of only as a photograph of the external world. They maintain that our knowledge develops in the form of thought, but demand of a "strictly objective science" that it takes its content only from the outside. The outside world must provide the material that flows into our concepts.9J. H. von Kirchmann even says in his "Lehre vom Wissen [als Einleitung in das Studium philosophischer Werke]" (Leipzig 1873, 3rd improved edition) that cognition is an influx of the external world into our consciousness. Without it, these are empty schemas without any content. If the outside world were to disappear, concepts and ideas would no longer have any meaning, because they are there for their own sake. This view could be called the negation of the concept. For it then no longer has any meaning for objectivity. It is something added to the latter. The world would also exist in all its perfection if there were no concepts. For they add nothing new to it. They contain nothing that would not exist without them. They are only there because the cognizing subject wants to make use of them in order to have that which is already there elsewhere in a form appropriate to it. For it, they are only mediators of a content that is non-conceptual in nature. Thus the view put forward.

[ 11 ] If it were well-founded, one of the following three premises would have to be correct.

[ 12 ] 1. the conceptual world is in such a relationship to the external world that it only reproduces the entire content of the latter in a different form. Here the external world is understood to be the sense world. If this were the case, then one could truly not see what necessity there would be to rise above the sense world at all. One has already given the whole to and fro of cognition with the latter.

[ 13 ] 2. The conceptual world takes up only a part of the "appearance for the senses" as its content. Think of it like this. We make a series of observations. We encounter the most diverse objects. We notice that certain characteristics that we discover in an object have already been observed by us. Our eye scans a series of objects A, B, C, D etc. A would have the characteristics q a r; B: 1mb n; C: k h cg and D:p na v. In D we again encounter the characteristics a and p, which we have already encountered in A . We refer to these characteristics as essentials. A and D have the same essential characteristics, we call them similar. Thus we summarize A and D by holding their essential characteristics in thought. Here we have a way of thinking that does not quite coincide with the world of the senses, to which the superfluousness criticized above does not apply and which is nevertheless just as far removed from adding anything new to the world of the senses. On the other hand, it can be said above all that in order to recognize which properties are essential to a thing, a certain norm is necessary which makes it possible for us to distinguish the essential from the non-essential. This norm cannot lie in the object, because it contains the essential and the non-essential in an undivided unity. This norm must therefore be the inherent content of our thinking.

[ 14 ] However, this objection does not completely overturn the view. For one can say: This is just an unjustified assumption that this or that is more or less essential for a thing. That does not concern us either. It is merely that we find certain identical properties in several things, and we then call the latter similar. There is no question of these identical properties being essential. But this view presupposes something that is not true at all. There is nothing really common in two things of the same kind if we stop at sense experience. An example will make this clear. The simplest is the best, because it is the easiest to grasp. Let's look at the following two triangles.

[ 15 ] What do they really have in common if you stop at sensory experience? Nothing at all. What they have in common, namely the law according to which they are formed and which causes them both to fall under the term "triangle", is only gained by us when we transcend sense experience. The term "triangle" encompasses all triangles. We do not arrive at it by merely observing all the individual triangles. This concept always remains the same, however often I may imagine it, while I will hardly succeed in looking at the same "triangle" twice. The fact that the single triangle is the fully determined "this" and no other has nothing to do with the concept. A certain triangle is this determined not by the fact that it corresponds to that concept, but by elements that lie entirely outside the concept: Length of sides, size of angles, position, etc. However, it is quite inadmissible to claim that the content of the concept "triangle" is borrowed from the objective world of the senses when one sees that its content is not contained in any sensory phenomenon at all.

[ 16 ] 3. There is now a third possibility. The concept could be the mediator for the apprehension of entities that are not perceptible to the senses, but which nevertheless have a character based on themselves. The latter would then be the non-conceptual content of the conceptual form of our thinking. Whoever assumes such entities existing beyond experience and grants us the possibility of knowledge of them must necessarily also see the interpreter of this knowledge in the concept.

[ 17 ] We will explain the inadequacy of this view in more detail. Here we only want to point out that it certainly does not speak against the content of the conceptual world. For if the objects that are thought about were beyond all experience and beyond thinking, then the latter would have to have all the more within itself the content on which it is based. It could not think about objects of which no trace could be found within the world of thought.

[ 18 ] In any case, it is clear that thought is not an empty vessel, but that it is full of content purely in itself and that its content does not coincide with that of another form of manifestation.