World Economy

GA 340

Lecture V

28 July 1922, Dornach

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We are now going to pursue a little further the sequence of events within the economic process which we considered yesterday. The economic process, as we have seen, is set in motion by human Labour working upon Nature, so that from the mere raw Nature-product—which has as yet no value in the economic process—we get the Nature-product transformed by human Labour. At the next stage, Labour is, as it were, caught up by Capital, which divides and organises it, till it eventually disappears in the Capital. For the further advance of the economic process, therefore, Capital itself must labour. But this labour of Capital is not labour in the old sense; rather the Capital is taken up by a purely spiritual activity. The economic process now goes forward by the Spirit “making good” the Capital, giving it additional value, as I described in the last lecture.

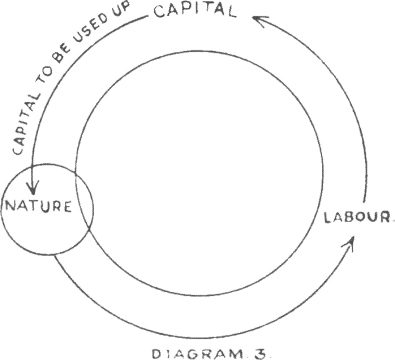

We must try to understand more and more the formula which was indicated yesterday. To this end, let me now describe diagrammatically—symbolically, as it were—what I explained yesterday. We may say: Nature goes under in human Labour (see Diagram 3. We have therefore this stream from Nature into Labour. Nature goes under in Labour. Labour continues to evolve. Then the values evolved stream onward, as it were, till Labour vanishes in Capital. We have traced the process up to this point (see Diagram 3). You can easily continue it for yourselves. The cycle must necessarily be completed in some way. The Capital cannot merely be blocked at this point, for otherwise we should be dealing not with an organic process but with one that would come to an end in Capital. The Capital must disappear once more into Nature. But you must first call to your aid another idea if you wish to understand this rightly.

Consider for a moment the economic process as we have traced it up to the present. First the elaboration of Nature by human Labour, then the organising of Labour by the Spirit and with it the rise of Capital, for Capital is a concomitant of the organising of Labour by the Spirit. Then the existence of Capital as such. Capital passes over from the Spirit which organised the Labour. The Capital becomes independent. The Labour disappears in its turn, and now the Spirit works in the Capital as inventive Spirit in connection with the whole social life. The technical aspect of invention need not concern us here; this will only come into question at a later stage.

If you now review all that I have described to you, you will see that I have presented everything from one side only. This was inevitable; for, apart from a few occasional hints, I have been speaking only of. production. I have indeed included, now and then, ideas that had to do with consumption, especially when we were trying to approach the question of price. But apart from that you will have found practically nothing about consumption in our discussions hitherto. I have been speaking of production. And yet, the economic process does not merely consist of production—it consists also of consumption.

A simple reflection will show you that consumption is exactly the opposite pole to production. We have been endeavouring to find the values that arise in the economic process within the sphere of production. Consumption on the other hand consists in a perpetual elimination of these values. In consumption they are constantly being used up. That is to say, it consists in a constant devaluation of the values. It is this that plays the other important part in the economic process—this constant devaluation of values. Indeed it is just through this that we have a certain right to call the economic an organic process, an organic process in which the Spirit presently intervenes. For it is of the essence of a living organism that something is continually being formed and again unformed. In any organism there must be a continual production and consumption, and this must be so in the economic organism too. There must be a constant producing and a using-up of what is produced.

At this point we begin to see in a different light, and from a different point of view, the value-creating forces which we have been considering. Hitherto we have only shown how values arise as the process of production takes its course. But now, every time a value approaches its moment of devaluation, the whole movement which we have been witnessing hitherto will change. So far, we have been observing a progressive, forward movement. Thus, values arise through the application of Labour to Nature; values arise through the application of the Spirit to Labour; values arise through the application of the Spirit to Capital. All this is a forward movement.

In fact, we have been observing the value-creating movement in the economic process. But as the devaluing factor of consumption enters into the process at every point, there will be something else as well. There will be that development of values which arises as between production and consumption themselves. When a value enters the process of consumption it no longer moves forward. It does not attain a higher degree of value, it no longer moves; for something now stands over against it. This is consumption—the development of a need. Here the value enters into a very' different sphere from that which we have hitherto been studying. We have been considering the value in its progressive, forward movement. (see Diagram 3) Now we must imagine it moving up to a certain point and being there arrested. Every time a value is arrested, there arises, not a further value-creating movement, but a value-creating tension.

This is the second element in the economic process. In the economic process we have not only value-creating movements but value-creating tensions. We can observe such value-creating tensions most conspicuously and simply where a consumer stands face to face with a producer or trader and in the very next moment the creation of value comes to an end, passing over into devaluation. Here there arises a tension—a tension which is maintained in equilibrium by the human need on the other side. Here the value-creating process is arrested. Human need or consumption confronts it and there arises the tension between production and consumption. This tension is also most decidedly a value-creating factor—albeit one that is comparable to a force that is arrested, held in equilibrium, rather than to a force that is working itself out. There is here a true analogy with the contrast in Physics between kinetic and potential energies—between kinetic energies and those energies of position where an equilibrium is brought about. If you do not take into account these energies of tension, these potential energies, in the economic process, you will be driven to the strangest misconceptions. Evolving the ideas as indicated here, we gain an intelligent conception of every economic relationship. Otherwise we are led into the greatest confusion. If, for example, you limit yourself to considering the movements of economic energies, you will never understand why the diamond in the King of England's crown has such an immense value. For here you are at once obliged to have recourse to the idea of economic tension-value. Many economists take into account the rarity of particular products of Nature; but we can never understand rarity as a value-creating factor if we regard the movement in the economic process as the only creator of values. We must also learn to understand how there arises here and there—most of all through consumption, but through other relationships as well—what I would call the creation of value by tensions, situations, equilibria.

Thus you see that devaluation can also take place in the economic process which, as I said, you can therefore regard as an organic process—an organic process in which Spirit constantly intervenes. There must be—or rather, there is constant devaluation. As the values proceed on their way (see Diagram 3) from Nature through Labour to Capital, they will be accompanied by a continual process of devaluation. What would happen if this corresponding devaluation could not take place? You can see this from the diagram.

To make it clear, let us consider the question of credit. To place Capital into the service of the Spirit in the sense which I explained yesterday, the man who produces by means of Spirit becomes a debtor. It is only through his having credit that he becomes or can become a debtor. At this point in our diagram credit steps in—the thing which may be properly called “personal credit.” A man has credit. The credit can be expressed in figures. The Capital which many others advance to him is, so to speak, his personal credit. Now, as you know, this personal credit has a certain consequence, at any rate if we consider it within our present economic conditions. Its economic effect is connected with the rate of interest.

Assume that the rate of interest is low. If as a spiritual creator in the economic process I become a debtor, that is to say, if I demand credit, I shall only have to pay a small sum for it. Having less interest to pay, I can produce my goods more cheaply. Thus I shall have a cheapening effect on the economic process. We may say, therefore: Personal credit cheapens production when the rate of interest falls. So long as the Capital continues to be turned to good account or made valuable by the Spirit in the economic process, it is always so. When the rate of interest goes down, he who requires credit has more freedom of movement. He can play his part far more intensively in the economic process—more intensively, that is to say, for his fellow-men. For if he cheapens his commodities he is playing a fruitful part in the process—at any rate from the point of view of the consumer.

But now let us take the other side. Assume that credit is given on land—“real credit.” When credit is given on land, the situation is essentially different. Assume that the rate of interest is 5%. A person borrowing Capital on the security of land must pay 5%. Capitalising this, you will get the Capital corresponding to the particular piece of land—that is to say, you will get the amount which would have to be paid to buy the piece of land outright. Assume now that the rate of interest falls to 4%. More Capital can then be “credited into” the land—this at any rate is what actually happens. Thus we see everywhere, as a result of a falling rate of interest, land becoming not cheaper but more expensive. When the standard rate of interest goes down, land does not become cheaper but more expensive. “Real credit” makes things more expensive while “personal credit” makes things cheaper. That is to say, real credit makes land more expensive while personal credit makes commodities cheaper. Now this means very much in the economic process. It means that, when Capital returns to Nature and simply unites with Nature in the form of real credit (in other words, when there is a union of Capital with land, that is to say, with Nature), then the economic process will tend more and more in the direction of dearness.

Thus the only sensible thing will be for the Capital at this point (see Diagram 3) not to preserve itself in Nature but rather to vanish into Nature. How then can Capital vanish into Nature? So long as it is at all possible to unite Capital with Nature—that is to say, so long as you can make Nature in its original unelaborated condition more and more expensive through the accumulation of Capital—so long as this is possible, Capital cannot vanish into Nature; on the contrary, it penetrates into Nature and maintains itself there. Thus in all countries where the law of mortgage makes it possible for Capital to unite with Nature, we shall find a congestion of Capital in Nature, i.e., in the land. Instead of the Capital being expended at this point (see Diagram 3)—instead of its disappearing at this point, instead of a value-creating tension arising—there is a further value-creating movement, which is harmful to the economic process. There is only one way of preventing this. In a healthy economic process we must not and cannot give “real credit ”—credit based on the security of land—even to a person working on the land. He too should only receive personal credit—that is to say, credit which will enable him to turn the Capital to good account through the land. If we simply unite the land with the Capital, the Capital will become congested the moment it arrives again at Nature (see the diagram). If on the other hand we unite it with the spiritual capacities of those who have to administer the land and further the economic process by working upon it, then, you see, the Capital vanishes. As it reaches Nature at this point, it will not become congested; it will not be preserved, but will go right on through Nature, back again into Labour, and will begin the cycle once more. It is one of the worst possible congestions in the economic process when Capital is simply united with Nature, that is to say, when (to trace the economic process hypothetically from its initial stages) after Labour and Capital have evolved from the starting-point of Nature, the Capital is enabled to take hold of Nature instead of losing itself in Nature.

At this point you may, of course, make a serious objection. In the course of this movement, you may say, the Capital has come into being. Suppose it now arrives again at Nature and there is too much of it. (It would be different if we were able to lead it over into Labour—if we were able, let us say, to invent new methods so as to further the exploitation of raw products. For in such a case we should be uniting not Nature but Labour with the Capital. If we arrive at this point with our Capital and exploit the raw products in a more economical way, or open out new sources or the like, then we are leading the Capital directly over into Labour). But suppose there is too much Capital. The several owners of Capital will become painfully aware of the fact; they will not be able to start anything with their Capital. This is indeed the case if you look into the matter historically. In actual fact, too much Capital did arise, and the only way out which it could find was to conserve itself in Nature. Thus we witnessed in the economic process the so-called rise in the value of land.

But, ladies and gentlemen, consider the matter in our present, larger context. The Land Reformers always describe these things in an inadequate way, so that the thing cannot be understood. Consider it in a larger context and you will say: If I unite Capital with Nature, the value of Nature will of course be enhanced. The more a thing is mortgaged, the more will eventually have to be paid for it. The value is constantly increased. But is this increase in the value of land a reality? No, it is no reality at all. By nature, land can never receive a greater value. It can at most receive a greater value by being worked upon in a more rational and scientific way, and in that case it is the Labour that increases the value. But to imagine the land itself, the land as such, increased in value is absurd. It is absolute nonsense. If you do improve the quality of the land, you only do so by working upon it. In so far as it is mere Nature, the land can have no value at all. All you can do is to give it a fictitious value by uniting Capital with it. So that we may say: What is called the value of land in the sense of present-day Economics is in real truth none other than the Capital fixed in the land. And the Capital fixed in the land is not a real value but an apparent value—a semblance of a value. That is the point. In the economic process it is high time that we learnt to under-stand the difference between real values and apparent values.

You see, if you have an error in your system of thought you do not observe its full effect to begin with. For however many disturbing processes in the organism are in fact connected with the error in thought, the connection is only recognisable by Spiritual Science. It escapes the crude Natural Science of today. People are unaware, for instance, how digestive and similar troubles in our peripheral organs arise as a result of such errors. But in the economic process it is just the errors and semblances which are obviously effective, which grow real and have real consequences. And, economically speaking, it makes no essential difference whether, for example, I issue money which has no foundation in reality but represents a mere increase in the amount of paper money, or whether I assign capital value to the land. In both cases I am creating fictitious values. By inflating the currency I increase the prices of things numerically, but in the reality of the economic process I effect absolutely nothing except a redistribution which may do immense harm to individuals. In like manner the above-described capitalising of land does harm to those who are involved in the economic process.

It would make a very interesting study to compare, for example, the mortgage laws existing before the War in the Mid-European countries with the English mortgage laws. In the Mid-European countries it was possible to screw the so-called value of land up and up and up without limit. The law itself made this possible. While in England on the other hand it is true to say, in a certain sense, that this is not so. Compare the effect on the economic process in the one case and in the other. The thing would make an interesting subject for a dissertation. It would make a very good subject, to compare statistically the working of the English mortgage laws with those of Germany.

I have thus illustrated the essential point in our present context. At this point (see Diagram 3) Nature simply must not be allowed to tend towards a conservation of Capital. Capital must be allowed to work on, unhindered, into Labour. But what is to happen if it is actually there—more of it than we are able to make use of? The only thing to prevent its being there in excess is to see that it is used up along this path (see diagram), so that in the last resort only so much of it is left at this point as can enter once more into the work to be done upon the land. That is to say only so much of it is left, as is required for this work. The essential and obvious thing is that the Capital should be used up, consumed along this path (see diagram). Indeed—assuming for a moment for the sake of hypothesis that it could be so—it would be a most appalling thing if nothing were consumed along this whole path. We should have to take the products with us. The process only becomes organic through the fact that things are used up. Just as the Nature-products, transformed by human Labour, get used up, just as the Labour which has been organised by Capital gets used up, so in its further path the Capital itself simply must be used up, properly used up. This using up of Capital is a thing which positively must be brought about.

It can only be brought about if the whole economic process from beginning to end—i.e., right up to its return to Nature—is ordered rightly. There must be something there like the “self-regulator” in the human organism. The human organism, at any rate when it is functioning normally, manages to prevent promiscuous deposits of unused foodstuffs. And if unused foodstuffs are deposited here or there, we are ill. Suppose, for instance, that in the process of digestion in the head, substances are deposited, that is to say, an irregular digestive process arises in the head. The substances that are deposited are no longer carried away—that is to say, their consumption is not properly regulated. Then we get migraine conditions. In like manner you will see the same principle at work in all parts of the human organism. The cause of morbid symptoms lies in the inadequate absorption and removal of what has to be digested. It is just the same in the social organism, when that which ought really to be used up at a certain point becomes accumulated. It is a matter of sheer necessity for the Capital to be used up along here, (see Diagram 3) in order that it may not unite with Nature and so become unliving—a petrified deposit, as it were, in the economic process. For capitalised land is in fact an impossible deposit in the economic process.

Let me expressly state that there can be no question here of any sort of political agitation. I simply unfold these matters as they take shape out of the natural process itself. We are only considering the scientific aspect. But a science that deals with human actions cannot possibly be pursued without indicating the kinds of morbid symptoms that can arise; just as we cannot study the human body without indicating the various possible morbid symptoms. There must, therefore, be a proportionate using up, consumption of Capital—certainly not a total consumption, for it is necessary that a certain amount should pass on, so that Nature may be elaborated once more.

This again I can make clear to you by a picture. Consider a farmer in his economic life. He must certainly try to get rid of the yield of his acres; but he must also keep sufficient seed for the next year. Seed must be preserved. This is a very apt comparison, and we may well apply it to the process we are now considering. Capital must be used up, until that alone remains which we may conceive as a kind of seed to kindle the economic process anew—once more from the starting-point of Nature. That alone must remain which may be necessary for a more scientific exploitation of natural resources—of raw products, or for an improvement of the land, let us say, by the creation of better manures and the like. Now in every such case Labour must be applied. Thus it is that amount of Capital, which can work on as Labour, which must be withdrawn from consumption. But before this point in the diagram is reached, the surplus Capital which would otherwise unite with Nature in an inorganic way must be used up.

Here you may say: “Well, tell us how it is to be done? How is it to be brought about that only just enough Capital arrives at this point for use as a seed for the future? Tell us how it is to be done.”

Well, ladies and gentlemen, in the science of Economics we stand on the ground, not of logic, but of reality. We cannot give the kind of answers which are sometimes given, for example, in the theory of ethics. In the theory of ethics we can admonish a criminal very soundly and we shall have done all that is required. But the economic process must go on, and we must speak of realities. When we spoke of Production, showing how it created economic values, we were indeed speaking of realities. And, that Consumption is a reality, everyone is well aware. In Economic Science one must always be speaking of realities. Ideas by' themselves have no effect in the real world. That which will rightly regulate the economic process, at this point in the diagram, finds expression in what I called the “Economic Associations ” in my book The Threefold Commonwealth.

If you make the economic life independent; if you bring together, in Associations suitably composed, the human beings who are actually taking part in the economic life—whether as producers, as traders or as consumers—then, through the economic process itself, these human beings will find it possible to arrest the formation of Capital if it is too intense and to stimulate it if it is too feeble.

This of course implies a right observation of the economic process. For instance, if at any place a certain kind of commodity becomes too cheap or too dear, those concerned must be able truly to observe the fact. The mere fact in itself is not the point. But when, through experiences which can only grow out of the concerted counsels of the Associations, they are able to say, as a result of such experiences: “Five units of money for so and so much salt are too little or too much, the price is too low or too high”—then and then only will they be in a position to take the necessary steps.

If the price of a commodity becomes too cheap, so that those who produce it can no longer receive sufficient remuneration for their excessively cheap services and their excessively cheap products, it will be necessary to assign fewer workers to this particular commodity. Workers will therefore have to be diverted to another piece of work. If, on the other hand, a commodity becomes too dear, workers will have to be led over into this branch of production. Thus the Associations will always be concerned with a proper employment of men in the several branches of the economic life. We must be clear on this. A real rise in the price of a given economic article indicates the necessity for an increase in the number of those who are working on this article, while an undue fall of price calls for measures to divert workers from this field of Labour to another. In reality we can only speak of prices in relation to the distribution of men among the several branches of Labour in a given social organism.

The kind of view that sometimes holds sway today, where people always have the tendency to work with notions rather than realities, is illustrated by some advocates of “free money” [“Freigeldleute”]. To them it appears quite simple. If prices anywhere are too high, so that too much money has to be spent in purchasing a certain article, they say: Let us see to it that the amount of money becomes less; then the commodities will be cheaper, and vice versa. But, if you think it out more deeply, you will find that this signifies nothing else for the economic process in reality, than as if by some mischievous device you were to cause the column of mercury to rise when the thermometer indicates that the room is too cold. You are only trying to cure the symptoms. By giving the money a different value you create nothing real.

You create something real if you regulate the Labour—that is to say, the number of people engaged on a certain kind of work. For the price depends on the number of workers engaged in a given field of work. To try to regulate these things bureaucratically, through the State, would be the worst form of tyranny; but to regulate it by free “Associations,” which arise within the social spheres, where everyone can see what is going on—either as a member, or because his representative sits on the Association, or he is told what is going on, or he sees for himself and realises what is required—that is what we must aim at.

Of course this also involves quite another social need. We must see to it that the worker is not restricted to one solitary manipulation throughout his life, but is able to turn his hand to other things. Moreover, as I beg you to consider, this will be necessary, if only for the reason that otherwise too much Capital would arrive at this point in the diagram. You can use up the surplus Capital, which would be excessive at this point, to instruct and educate the workers in one thing or another, so as to be able to transplant them into other callings. You see, therefore, the moment you think in a rational way, the economic process will correct itself. That is the essential thing. It will never correct itself if you say: “By this or that measure, by inflation or by the issue of such or such official instructions, the thing will be improved.” By such means it will never be improved. It will only be improved by enabling the economic process to be clearly and transparently observed at every place, assuming always that those who make the observations are in a position to follow them out to their logical conclusions.

I wanted to reach this point in our argument today, in order that you might see that there was no question of starting any “agitations” with the “Threefold Commonwealth” as we intended it. We wanted to tell the world what follows from a real and true study of the economic process itself.