The Life of Man on Earth and the Essence of Christianity

GA 349

14 March 1923, Dornach

Automated Translation

IV. Dante's Conception of the World and the Dawn of the Scientific Age

I have received a question regarding the colors, and I have been asked to say something about it.

First, I will address the question that was asked first here. That is the question about the world view that Dante had. So the gentleman has read Dante. And when you read Dante, this poet from the Middle Ages, you see that he had a very different world view than we do.

Now I ask you to consider the following. People, as I have often told you, think that what people know today is actually the only thing that is true. And when earlier people thought differently, people imagine: well, that was just the way it was. And they waited until they could learn something sensible about the world.

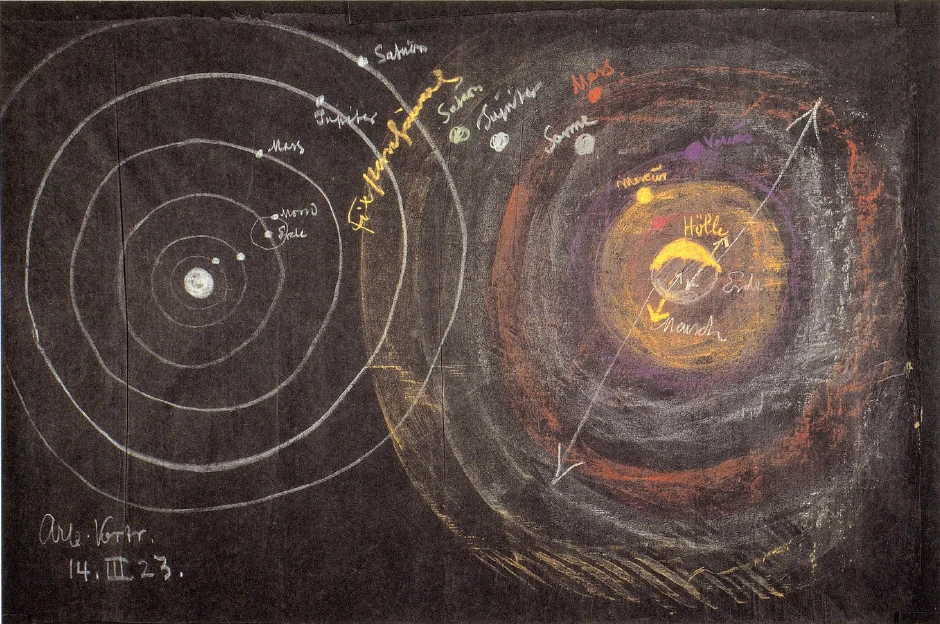

You see, what people learn in school today, what becomes second nature to them in terms of the world view, has actually only been around since Copernicus first conceived of this world view. According to this 16th-century world view, it was imagined that the sun is at the center of our entire planetary system. Mercury (see drawing on page 70), then Venus, then the Earth revolved around the Sun. The Moon revolves around the Earth. Mars comes next, revolving around the Sun. Then there are many other planets, tiny in relation to the universe, which are called planetoids – oids, meaning similar to planets. Then comes Jupiter, then Saturn. And then Uranus and Neptune; I don't need to draw them, because they're not visible from here. That's how we imagine it today, we learn it at school, that the sun stands still in the middle. Actually, these lines, in which the planets revolve, are somewhat elongated. That's not what matters to us today. So we imagine that first Mercury, then Venus, then the Earth revolves around the Sun. Now you know that the Earth orbits the Sun in a year, or 365 days, six hours, and so on. Saturn orbits once in about thirty years, so much slower than the Earth. Jupiter, for example, orbits in twelve years, so also slower than the Earth. Mercury orbits quite quickly. So the closer the planets are to the Sun, the faster they orbit.

Well, that's not the right idea today, it's what they teach in school. But we only need to go back to the 14th century, around 1300, and such an extraordinarily great mind as Dante, who wrote the Divine Comedy, had a completely different idea. This goes back a few centuries to before Copernicus. And the greatest man of all, the greatest man in terms of intellect, Dante, had a completely different idea.

Now, today, let's not decide whether one is right or the other is right. Let us just imagine how Dante, the greatest mind of his time, conceived the matter in a time - now it is 1900, then it was 1300 - that is only six hundred years ago. Let us not think that one is wrong and the other is right, but let us just put ourselves in Dante's shoes and see how he imagined it. He imagined (see drawing): The Earth is at the center of the world system. And this Earth is not just there so that the Moon, for example, reflects the light that it receives from the Sun back to the Earth, but this Earth is not only surrounded, but completely enveloped by the sphere of the Moon. The Earth is completely inside the sphere of the Moon. Dante imagined the Moon to be much larger than the Earth. He imagined: That is a very fine body, which is much larger than the earth. It is therefore fine, but much larger. And what you see is only a small piece, namely the solid piece of the moon. And this solid piece, it only goes around the earth. Can you imagine that? With Dante, it is so that the earth is inside the moon, and what you see of the moon, that is only a small, fixed piece of the moon. That goes around. But actually we are all inside the forces of the moon. I have drawn that in red.

And now Dante imagined: Yes, if the Earth were not inside these forces of the Moon, then, by some miracle, people would come to Earth, but they would not be able to reproduce. It is the reproductive forces that are contained in the red-drawn area. They also flow through people and make them capable of reproduction. So Dante imagined: The Earth is a solid, small body; the moon is a fine - much finer than the air -, a fine large body in which the Earth is inside like a core. You can imagine it as if the Earth were a plum kernel in the soft flesh of a plum. And out there is the solid piece; that moves around. But that there (see drawing, moon) is also always there, and that causes that man is capable of reproduction, and the animals are also capable of reproduction.

Now he imagined further: The Earth is not only in the moon's forces, but the Earth is also in other forces, which I will show here in yellow, and they permeate everything. So the moon's forces are in there, stuck in there, so that the Earth and the moon are in turn in there in this yellow. And there is another solid piece. This solid piece is Mercury, and it goes around there. And if man were not constantly permeated by these Mercury forces, he could not digest. So Dante imagined: the Moon forces cause reproduction; the Mercury forces, in which we are also always immersed, only finer than the Moon forces, cause us to digest and cause animals to digest. Otherwise, our body would be nothing more than a chemical laboratory, he imagined. The fact that our body functions differently than a chemical laboratory, where you only mix the substances and then separate them again, is caused by the Mercury forces. Mercury is larger than the Earth and larger than the Moon.

And now all this is in turn contained in an even larger sphere, as Dante called it. So we are also immersed in the forces that come from this planet, from Venus. So we are immersed in all these forces, which permeate us. We are also permeated by the forces of Venus. And the fact that we are permeated by the forces of Venus means that we can not only digest, but also absorb the digested into the blood. Venus forces live in our blood. Everything that is connected with our blood comes from the forces of Venus. This is how Dante imagined it. And these Venus forces also cause, for example, what a person has in his blood as feelings of love; hence “Venus”.

The next sphere is the one we are in, and there the sun revolves as a fixed body. So we are in the sun everywhere. For Dante in 1300, the sun is not just the body that rises and sets, but the sun is everywhere. When I stand here, I am inside the sun. Because what rises and sets, what moves around, is only a piece of the sun. That's how he imagined it. And it is mainly the powers of the sun that are active in the human heart.

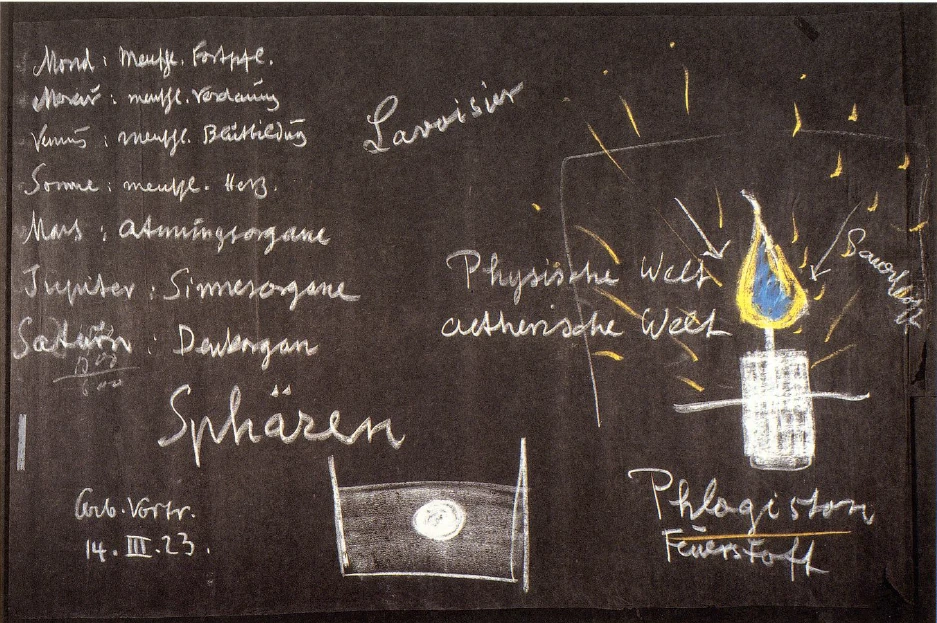

So you see: the moon, human and also animal reproduction; Mercury: human digestion; Venus: human blood formation; the sun: the human heart.

Now Dante imagined that all of this is in turn contained in the huge sphere of Mars. There is Mars. And this Mars, in which we are also embedded, is just as connected to the human heart as the sun is, and is also connected to everything that concerns our breathing and especially our speech, to everything that is the respiratory organs. That is in Mars. So Mars: respiratory organs. And then it continues. The next sphere is the Jupiter sphere. We are again immersed in the forces of Jupiter. Now, Jupiter is very important; it is connected with everything that is our brain, actually our sense organs, our brain with the sense organs. Jupiter is therefore connected with the sense organs. And now comes the outermost planet, Saturn. In this, everything is included again. And Saturn is connected with our thinking organ.

Moon: Human Reproduction

Mercury: Human Digestion

Venus: Human Hematopoiesis

Sun: Human Heart

Mars: Respiratory Organs

Jupiter: Sensory Organs

Saturn: Organs of Thought

So you see, that Dante, who was only six hundred years behind us, imagined the whole world differently. He imagined, for example, Saturn as the largest planet, albeit made of fine material, but as the largest planet, in which we are embedded. And these Saturn forces, our thinking organs bring about that we can think.

Outside of all this, but in such a way that we are also inside it, is the fixed starry sky. So there are the fixed stars, namely the zodiacal fixed stars (see drawing). And even greater is that which moves everything, the first mover. But it is not only up there, but it is also the first mover here everywhere. And behind it is eternal rest, which is also everywhere. That's how Dante imagined it.

Now, today's man can say: It's just that people saw all this imperfectly; but today we have finally come to know how things are. – Of course, that can be said on the one hand. But Dante was not exactly stupid either, and what the others see today, he also saw. So he was not exactly stupid. And the others from whom he took it, they all believed it back then, they were not all foolish people either, but they imagined it differently. And now the question is: how is it that in world history, people used to think differently about the whole world, and then suddenly in the 16th century everything is turned upside down and a completely different idea of the world is presented?

That is, of course, a very important question, gentlemen. And you can't get around saying that these earlier ideas were just childish, but that these people saw something completely different from what people see today. You have to be clear about that: they saw something completely different. Today's people are terribly good at thinking. Yes, today's people are so good at thinking that the ancients could not match them. Thinking had only just emerged. The ancients always had a terrible respect for Saturn, which is connected with the organ of thinking. They thought that Saturn corrupts the human being. Too much thinking is not good. Saturn has always been considered a dark planet. And the forces that came from Saturn, they thought, if they were too strong in a person, he would become very melancholy. He would think all the time and become melancholy. So these people did not particularly like the forces of Saturn, and they imagined them much more in images. They did less calculating. Today we calculate everything. This whole world view here from Copernicus is calculated. But these ancient people did not calculate. But these ancient people knew something else that today's people do not know. They knew that everywhere in the world, wherever we look, there are many forces. But the forces that are within man are not in that which is seen with the eye, but are within the invisible.

And so Dante said to himself: There is a visible world, and there is an invisible world. The visible world, well, that is the one we see. When we look out at night, we see the stars, the moon, Venus and so on. That is the visible world. But the invisible world is also there. And the invisible world is these - they were called spheres back then. The invisible world consists of these spheres. And a distinction was made between the world that is seen with the eyes, which was called the physical world. That was the physical world. And then there was the world that is not seen with the eyes. That is the world that Dante meant, and it was called the ethereal world. So the ethereal world, the world that consists of such a fine substance that you can see through it all the time.

Yes, gentlemen, I don't know if it has happened to you, but I have met people who have claimed that there is no air because you can't see it. They said: Yes, when I go from there to there, there is nothing there; I'm not walking through something. — You know that there is air where I am walking through. But, as I said, I have met people who were not as schooled as today's people are schooled, and they didn't believe that there was air; they said: There is nothing there. - Dante, who knew that there is not only air, but also the moon, Venus and so on. It is exactly the same. They say: I walk through the air. Dante said: I walk through the moon, I walk through Venus, I walk through Mars. — That's the whole difference. And all that you do not see in the usual way, and what you can not perceive by the usual physical and chemical instruments, that was called the ethereal world. So Dante described a completely different world, an ethereal world. And what is the reason for the fact that six centuries ago Dante saw the world differently? The reason is that he described something different, that he described the invisible, the ethereal world. And Copernicus said nothing other than: Oh, let's not worry about the ethereal world and let's describe the physical world. That is where progress lies. One should not imagine that Dante was a “fool”, but he simply described the etheric world and not the physical. The physical world was not particularly important to him. He described the etheric world.

Now, you see, this situation basically only changed significantly at the end of the 18th century. Until the end of the 18th century, people still knew something about this etheric world. In the 19th century, they no longer knew anything about it. We come to this again through anthroposophy. In the 19th century, people knew nothing about this etheric world.

Regarding the other question:

If we go back to the 18th century, people did the following, for example. They said: Here we have a candle; there is the wick; there the candle is burning. Now you know that when a candle is burning, it is bluish in the middle and yellowish at the edge. You can work this out in detail using what we have said about colors. Namely, in the middle it is dark, and here it is light (on the outside at the edge). And the consequence of this is that one sees the darkness through the light. And you know, as I told you the other day, when one sees the darkness through the light, it appears blue.

That is why the inside of the burning candle appears blue, because you see the darkness through the light there. I just wanted to draw your attention to this so that you see: the color thoughts, the color views that I told you last time can be applied to everything.

But now you know that when the candle burns, it becomes less and less. The flame is at the top, and what melts here (on the candle) merges into the flame. Finally, the candle is no longer there. What is in the candle has spread into the air.

Now imagine someone, let's say in 1750, so not even two hundred years ago; who said: Yes, when the candle burns and everything disappears into thin air, then something of the candle goes out into the free space. Ultimately, there is nothing left. So the whole candle must go out into free space. He went on to say that it consists of very fine matter, fire matter. This fine fire matter connects with the flame and goes out in all directions. So that the man in 1750 still said: There in this wax, there is a substance that is only piled up, sealed. When the flame makes it fine, it goes out into the free space. This substance was called phlogiston in those days. So something goes out of the candle. The fuel, the phlogiston goes away from the candle.

Now, at the end of the 18th century, another one came along. He said: No, I don't really believe the story that there is a phlogiston that goes out into the world. I don't believe that! - What did he do? He did the following. He also burned the whole thing, but he burned it in such a way that he collected everything that had formed there. He burned it in a closed room so that he could collect everything that could form there. And then he weighed it. And then he found that it does not become lighter. So he weighed the whole candle first, and then he weighed the piece that was left when the candle had burned so far (it is drawn); and what was formed during the burning, he caught it, weighed it and found that it was then a little heavier than before. So, when something burns, he said, what is formed is not lighter, but becomes heavier.

And this person who did that was Lavoisier. So what was it that gave him a completely different view? Yes, it was because he used the scales first, he weighed everything. And then he said: if this is heavier, then something must not have gone away, phlogiston must not have gone away, but something must have been added. That is oxygen, he said. So, first, it was imagined that the phlogiston flew away, and then it was imagined that when something burns, oxygen actually enters, and combustion is not the dispersion of phlogiston, but precisely the attraction of oxygen. This has come about because Lavoisier weighed first. In the past, people did not weigh.

You see, gentlemen, here you can grasp with your hands what actually happened. At the end of the 18th century, people no longer believed in anything that could not be weighed. Of course, phlogiston cannot be weighed. Phlogiston is already leaving. Oxygen is also approaching. But oxygen, when it combines, can also be weighed. But the phlogiston cannot be captured. Why not? Yes, everything that Copernicus observed in Mars and Jupiter is that which is heavy when weighed. What Copernicus calls Mars is that which, if placed on a large scale, would weigh something. Likewise, what he calls Jupiter. He merely observed the heavy bodies.

Dante did not just observe heavy bodies, but precisely that which has the opposite of heaviness, that which always wants to escape into space. And phlogiston is simply one of the things that Dante observed, and oxygen is one of the things that Copernicus observed. Phlogiston is the invisible that dissipates, the ether. Oxygen is a substance that can be weighed.

So you see how materialism came about. This is something that can become extremely important to you. Materialism came about because people began to believe only in what they could weigh. But what Dante still saw cannot be weighed. If you walk around here on earth, you can also be weighed. You are heavy, and if you call only what is heavy a human being, then you have only the earthly human being. But just imagine that this earthly human being becomes a corpse. Everything heavy, everything that can be weighed, becomes a corpse. Then the corpse lies there. You can still live in what is not heavy, in what surrounds the earth, and what materialism denies, what Dante still speaks of, what we must speak of again, that it is there. So that we can say: When man lays aside his outer, heavy body, which can be weighed, he remains in the etheric body for the time being.

But now I want to tell you what is actually contained in this etheric body. You see, when there is a chair here, I can see this chair. I have an image of this chair within me. But if I turn around, I don't see it. But I still have an image of it inside me, really still an image. This image is the memory image.

Now think of the memory images. Think that a long time ago you experienced something. For example, let's say you were somewhere and saw people dancing merrily in a marketplace and so on. I could also mention something else. You have kept the image. That is no longer there, gentlemen, what you have as an image, especially no longer there among the things that can be weighed, that are heavy, it is no longer there anywhere. It can only be imagined in you. You can go around today and, if you have a vivid imagination, you can easily imagine what it was all like, right down to the colors of those who jumped around. You have the whole picture in front of you. But you won't think for a moment that what you saw back then can be weighed. You can put this on a scale. The individual people have their own weight. But what you carry within you today as memory pictures cannot be put on the scales. It does not exist in that form. It has remained, although the thing itself is no longer there in the physical sense. How is it, then, that what is in you is a memory picture? It is in you in an ethereal form. It is no longer in you in the physical sense, but in an ethereal one.

Now imagine you are swimming and, by some misfortune, you are close to drowning; but you are saved. Such people, who were close to drowning and have been saved, have mostly told of a very interesting memory picture. This memory picture can also be had when you are not drowning, but when you are training in spiritual science, anthroposophy. Those who were close to drowning have an overview of their entire earthly life, right back to childhood. Everything rises up. Suddenly a memory picture is there. Why? Yes, gentlemen, because the physical body, which is now in the water, is going through something very special. And then you have to remember something that I told you at the time. I told you: if you have water here and a body in it, the body in the water becomes lighter. It loses as much of its weight as the water weighs, which, as a watery body, is just as large as itself.

It's a nice story about how this was discovered. It was discovered in ancient Greece that every body in the water becomes lighter. Archimedes thought a lot about such things. And once Archimedes was bathing. The people were highly astonished – yes, in Greece they bathed in such a way that the others saw it too; it was in Sicily, which belonged to Greece at the time – the people were highly astonished when Archimedes suddenly jumped out of the bath and shouted: Eureka! Eureka! Eureka! That means: I've found it! – The people thought: What on earth could he have found in the bath? He was submerged up to his head in the bath, with one leg sticking out of the water, and he realized that when he took one leg out of the water, it became heavier; when he put it back in, it became lighter again. That was the first time he had realized in the bath that every body becomes lighter when it is in the water. This is the so-called Archimedes' principle. So every body is lighter when it is in the water. So also, when a person is drowning, his physical body becomes lighter, very light. Now, what he has in the etheric body can still hold on, and that is where all his memories arise. And you see, the memories arise from the bottom because he is no longer so heavy. When a person dies, when he has completely left his physical body, his physical body, he is very light. He lives entirely in the etheric sphere. And after his death, a person always has a complete memory of what he has experienced on earth, up to childhood. That is the first experience one has after death: a complete memory.

This memory can be examined. Namely, it can be examined by training oneself in the way I have described in my book: “How to Know Higher Worlds.” Then one can always have this memory. Then one knows that the soul becomes independent of the body. Then it first receives this memory, because at first it does not live in the material that can be discarded, but on the contrary, it wants to go out into the world. That is the first state after death. Then one remembers. I would like to describe the second state to you next time. But now I want to describe something that prepares us. Because the question that has been asked is an awfully difficult one.

If we consider that Dante had a conception of the world that modern man regards as childish, then what he further imagines is even more childish for modern man. For if there is a man standing for Dante on the earth (it is being drawn), then Dante imagines: Here on Earth, turned away – so if you go through there – you would have what he imagines as hell inside the Earth. So he thinks: out there, there is celestial ether everywhere. But if I were to drill into the Earth, there is hell on the other side. Before I come out of the Earth, there is hell.

Now, to see this as childish is terribly easy for today's man. One need only say: Yes, but Dante would not have needed to stand there, but here, then he could have drilled in there, and then there would have been (on the other side) hell! - Of course, today's man can say that because today's man knows that there are people living on the other side as well. So he can easily say: Yes, Dante was just stupid; he was not able to understand that the earth has people on all sides, and that therefore hell could be just as easily here as there. Because the one who is standing there now receives heaven from that side, and for him hell would then be on the other side.

You see, gentlemen, that is how it is. For the physical world, it can only be like this: if there were heaven, hell could only be here; for the physical world, it could only be like this. If a chair is standing somewhere, it can only stand there. There is no other place where it could be.

But that is not how Dante imagined it. He did not imagine the physical world at all, but he did imagine forces. And he said: Yes, when a person stands there, and he moves with his own etheric body in the upward direction, then he becomes lighter and lighter. Then he overcomes more and more the force of gravity. But when he goes into the earth, he has to make more and more effort, and this effort is greatest when he has reached the other end. There everything presses on him. There the heaviness is greatest. It does not depend on there being some particular hell there, but on having gone through it to get there. (see Drawing)

And if Dante imagined it that way, then he could also stand there (at the other end). When he moves out from there, he becomes lighter and lighter, as he enters more and more into the ether. But when he moves into the earth, he has to go through that (heaviness). Then he experiences the state where I have drawn green; but earlier, where I have drawn yellow. So it depends on that. Dante does not say that this is precisely where hell is, but rather that when someone has to work their way through the earth with their etheric body, it is so difficult that wherever they go, whether up or down, they experience hell. It is only in recent times that people have begun to imagine hell as a specific place. Dante had in mind the experience that one has when one, as an etheric human, has to work one's way through the earth.

If someone says: Dante was stupid – then that reflects badly on him, because he is stupid enough to say that Dante imagined that hell was at the other end of the earth. No, Dante imagined: wherever I fly above the earth into heaven, I become lighter in soul; wherever I go into the earth, wherever I go to the other end: hellish.

So the whole idea was different. And only when you can take into consideration the very different way in which people have imagined it, can you also understand what I will answer you next time: What remains of the earthly man when he has passed through the gate of death?

If today was a little more difficult than usual, you must bear in mind that it was because of the question. I hope it has become a little clearer. We will then move on on Saturday and look at the human being when he passes through death and what then becomes of him.

IV. Das Weltbild Dantes und das Heraufkommen des naturwissenschaftlichen Zeitalters

Ich habe eine Frage in bezug auf die Farben bekommen und werde gebeten, darüber noch etwas zu sagen.

Nun will ich zunächst eingehen auf die Frage, die hier zuerst gestellt worden ist. Das ist die Frage nach dem Weltbilde, das sich Dante gemacht hat. Also der Herr hat Dante gelesen. Und wenn man Dante, diesen Dichter aus dem Mittelalter, liest, so sieht man, daß er ein ganz anderes Weltbild gehabt hat als wir.

Nun bitte ich Sie, folgendes zu bedenken. Die Menschen, ich habe es Ihnen ja öfter gesagt, denken, daß dasjenige, was heute der Mensch weiß, eigentlich das allein Gescheite ist. Und wenn frühere Menschen anders gedacht haben, dann stellen sich die Leute vor: Nun ja, das war da einmal so. Und man hat gewartet, bis man etwas Vernünftiges über die Welt hat erfahren können.

Sehen Sie, dasjenige, was heute die Leute in der Schule schon lernen, was ihnen in Fleisch und Blut übergeht über das Weltbild, das ist eigentlich erst so seit der Zeit, als Kopernikus dieses Weltbild zuerst ausgedacht hat. Nach diesem Weltbild also aus dem 16. Jahrhundert hat man sich vorgestellt, daß die Sonne in der Mitte unseres ganzen Planetensystems steht. Um die Sonne laufen zunächst herum der Merkur (Zeichnung Seite 70), dann die Venus, dann die Erde. Um die Erde läuft wiederum der Mond herum. Dann kommt der Mars, um die Sonne herumlaufend. Dann sind viele, im Verhältnis zum Weltenraum winzige Planeten da, die man Planetoiden nennt - oid, das heißt ähnlich, ähnlich den Planeten. Dann kommt der Jupiter, dann kommt der Saturn. Und dann noch Uranus und Neptun; die brauche ich nicht zu zeichnen, So stellt man sich das heute vor, lernt es schon in der Schule, daß die Sonne in der Mitte stillsteht. Eigentlich sind diese Linien, in denen die Planeten herumlaufen, etwas langgestreckt. Auf das kommt es uns heute nicht an. Man denkt sich also, daß zunächst Merkur, dann Venus, dann die Erde um die Sonne herumläuft. Nun wissen Sie, daß die Erde um die Sonne in einem Jahr herumläuft, also in 365 Tagen sechs Stunden und so weiter. Der Saturn läuft in ungefähr dreißig Jahren einmal herum, also wesentlich langsamer als die Erde. Der Jupiter zum Beispiel läuft in zwölf Jahren herum, also auch langsamer als die Erde. Der Merkur läuft ziemlich schnell herum. Also je näher die Planeten der Sonne sind, desto schneller laufen sie herum.

Nun, nicht wahr, diese Vorstellung hält man heute für die richtige, lehrt sie schon in der Schule. Wir brauchen aber nur bis zum 14. Jahrhundert zurückzugehen, also 1300 etwa, dann hat ein so außerordentlich großer Geist, wie Dante, der dieses Gedicht von der Göttlichen Komödie gemacht hat, noch eine ganz andere Vorstellung. Das liegt also ein paar Jahrhunderte zurück hinter Kopernikus. Und der allergrößte Mensch, der dem Geist nach allergrößte Mensch, Dante, hat eine ganz andere Vorstellung.

Nun wollen wir heute einmal zunächst gar nicht entscheiden, ob das eine richtig ist oder das andere richtig ist. Wir wollen uns jetzt nur einmal vorstellen, wie Dante, dieser bedeutendste Geist der damaligen Zeit, sich die Sache vorgestellt hat in einer Zeit also — jetzt haben wir 1900, damals 1300 -, die nur sechshundert Jahre zurückliegt. Wollen wir gar nicht denken, das eine ist falsch, das andere ist richtig, sondern uns nur hineinversetzen, wie Dante sich das vorgestellt hat. Der hat sich vorgestellt (Zeichnung Seite 73): Die Erde steht in der Mitte des Weltensystems. Und diese Erde ist nicht nur so da, daß der Mond zum Beispiel das Licht, das er von der Sonne bekommt, auf die Erde zurückwirft, sondern diese Erde, die ist nicht nur umgeben, sondern ganz eingehüllt von der Mondensphäre. Die Erde steckt ganz drinnen in der Mondensphäre. Den Mond hat sich Dante also viel größer vorgestellt als die Erde. Er hat sich vorgestellt: Das ist ein sehr feiner Körper, der viel größer ist als die Erde. Der ist also zwar fein, aber viel größer. Und das, was man sieht, das ist nur ein Stückchen, nämlich das feste Stückchen von dem Mond. Und dieses feste Stückchen, das läuft nur um die Erde herum. Können Sie sich das vorstellen? Bei Dante ist es so, daß die Erde im Mond drinnen ist, und das, was man sieht vom Mond, das ist nur ein kleines, festes Stückchen vom Mond. Das läuft herum. Aber eigentlich sind wir alle in den Kräften vom Mond drinnen. Die habe ich da rot gezeichnet.

Und nun hat sich Dante vorgestellt: Ja, wenn die Erde nicht drinnensteckte in diesen Kräften vom Mond, so würden zwar einmal durch irgendein Wunder auf die Erde Menschen kommen, aber sie könnten sich nicht fortpflanzen. Die Fortpflanzungskräfte sind es, die da in dem Rotgezeichneten drinnen enthalten sind. Die durchströmen auch den Menschen, und die machen, daß er fortpflanzungsfähig ist. Also der Dante hat sich vorgestellt: Die Erde ist ein fester, kleiner Körper; der Mond ist ein feiner — viel feiner als die Luft -, ein feiner großer Körper, in dem die Erde wie ein Kern drinnen ist. Sie können sich das so vorstellen, als wenn die Erde ein Zwetschgenkern wäre in dem weichen Zwetschgenfleisch. Und da draußen ist das feste Stückchen; das läuft herum. Aber das da (Zeichnung Seite 73, Mond) ist auch immer da, und das bewirkt, daß der Mensch fortpflanzungsfähig ist, und die Tiere auch fortpflanzungsfähig sind.

Jetzt stellte er sich weiter vor: Die Erde ist jetzt nicht nur drinnen in Mondenkräften, sondern die Erde ist auch noch in weiteren Kräften drinnen — die will ich hier gelb zeichnen -, und die durchdringen das alles. Also die Mondenkräfte sind in dem drinnen, stecken da drinnen, so daß Erde und Mond wiederum da drinnen in diesem Gelben sind. Und da ist wiederum ein festes Stück. Dieses feste Stück ist der Merkur, und der läuft da herum. Und wenn der Mensch nicht fortwährend von diesen Merkurkräften durchdrungen wäre, so könnte er nicht verdauen. So daß sich also Dante vorgestellt hat: Die Mondenkräfte bewirken die Fortpflanzung; die Merkurkräfte, in denen wir auch immer drinnenstecken, die nur feiner sind als die Mondenkräfte, die bewirken, daß wir verdauen können, und daß die Tiere verdauen können. Sonst hätten wir in unserem Leib nur ein chemisches Laboratorium, stellte er sich vor. Daß es in unserem Leib anders zugeht als in einem chemischen Laboratorium, wo man nur die Stoffe mischt und wiederum voneinander trennt, das wird von den Merkurkräften bewirkt. Also der Merkur ist größer als die Erde und größer als der Mond.

Und nun ist das alles wiederum drinnen in einer noch größeren Sphäre, wie Dante es nannte. So daß wir also auch in den Kräften drinnenstecken, die von diesem Planeten, von der Venus, kommen. Also wir stecken in all diesen Kräften drinnen, die durchdringen uns. Wir sind also auch von den Venuskräften durchdrungen. Und daß wir von den Venuskräften durchdrungen sind, das macht, daß wir nicht nur verdauen können, sondern das Verdaute ins Blut aufnehmen können. Venuskräfte leben in unserem Blute. Alles, was mit unserem Blut zusammenhängt, kommt von den Venuskräften. So stellte es sich Dante vor. Und diese Venuskräfte, die bewirken zum Beispiel auch dasjenige, was der Mensch in seinem Blut als Liebesgefühle hat; daher «Venus».

Die nächste Sphäre ist dann diejenige, in der wir wiederum drinnenstecken, und da läuft wiederum als festes Stück die Sonne herum, Wir sind also überall in der Sonne drinnen. Die Sonne ist für Dante im Jahre 1300 nicht nur der Körper, der da auf- und niedergeht, sondern die Sonne ist überall da. Wenn ich hier stehe, bin ich in der Sonne drinnen. Denn das ist nur ein Stück von der Sonne, was da auf- und niedergeht, was da herumläuft. So hat er es sich vorgestellt. Und die Sonnenkräfte sind es vorzugsweise, welche im menschlichen Herzen tätig sind.

Also Sie sehen: Mond, menschliche und auch tierische Fortpflanzung; Merkur: menschliche Verdauung; Venus: menschliche Blutbildung; Sonne: menschliches Herz.

Jetzt hat sich Dante vorgestellt: Alles das ist wiederum in der riesig großen Marskugel drinnen. Da ist der Mars. Und dieser Mars, in dem wir also wiederum drinnenstecken, der hängt ebenso, wie die Sonne mit dem menschlichen Herzen zusammenhängt, mit alledem zusammen, was unsere Atmung und namentlich unsere Sprache betrifft, mit allem, was die Atmungsorgane sind. Das ist im Mars. Also Mars: Atmungsorgane. Und dann geht es weiter. Die nächste Sphäre ist dann die Jupitersphäre. Wir stecken wiederum in den Jupiterkräften drinnen. Nun, der Jupiter, der ist ja sehr wichtig; der hängt mit alledem zusammen, was unser Gehirn ist, eigentlich unsere Sinnesorgane, unser Gehirn mit den Sinnesorganen. Der Jupiter also hängt zusammen mit den Sinnesorganen. Und nun kommt der äußerste Planet, der Saturn. In dem ist wieder alles das drinnen. Und der Saturn hängt zusammen mit unserem Denkorgan.

Mond: Menschliche Fortpflanzen

Merkur: Menschliche Verdauung

Venus: Menschliche Bluttbildung

Sonne: Menschliche Herz

Mars: Atmungsorgane

Jupiter: Sinnesorgane

Saturn: Denkorgane

Also sehen Sie, dieser Dante, der nur sechshundert Jahre hinter uns zurückliegt, der stellte sich das ganze Weltgebäude anders vor. Der stellte sich zum Beispiel den Saturn als den größten Planeten vor, allerdings von feinem Stoff, aber als den größten Planeten, in dem wir drinnenstecken. Und diese Saturnkräfte, die bewirken unsere Denkorgane, die bewirken, daß wir denken können.

Außerhalb nun von alledem, aber so, daß wir da auch drinnen sind, ist der Fixsternhimmel. Da sind also die Fixsterne, namentlich die Tierkreis-Fixsterne (Zeichnung Seite 73). Und noch größer ist dann dasjenige, was alles bewegt, der erste Beweger. Aber der ist nicht bloß da oben, sondern der ist auch hier überall der erste Beweger. Und hinter dem ist ewige Ruhe, die auch wiederum überall ist. So stellte sich das Dante vor.

Nun, nicht wahr, kann der heutige Mensch sagen: Das ist eben so, daß die Leute das alles noch unvollkommen gesehen haben; aber heute sind wir endlich dahin gelangt, daß wir wissen, wie die Sachen sind. — Gewiß, das kann man auf der einen Seite sagen. Aber Dante war eben auch nicht gerade dumm, und dasjenige, was die andern heute sehen, das hat er schon auch gesehen. Also dumm war er nicht gerade. Und die anderen, von denen er das genommen hat, die alle dazumal das geglaubt haben, die waren eben auch nicht alle törichte Menschen, sondern man hat sich das anders vorgestellt. Und jetzt ist die Frage: Ja, wie kommt es, daß es in der Weltgeschichte so eingetreten ist, daß die Menschen über das ganze Weltgebäude früher anders gedacht haben, und dann plötzlich im 16. Jahrhundert alles drunter und drüber werfen und eine ganz andere Vorstellung vom Weltbild bekommen?

Das ist ja natürlich eine sehr wichtige Frage, meine Herren. Und damit kommt man nicht zurecht, daß man sagt, nun ja, diese früheren Vorstellungen waren eben kindisch, sondern diese Leute haben eben noch ganz etwas anderes gesehen, als die heutigen Menschen sehen. Darüber muß man sich klar sein: die haben noch etwas ganz anderes gesehen. Die heutigen Menschen, die können so furchtbar gut denken. Ja, so gut denken, wie die heutigen Menschen, konnten diese alten Menschen nicht. Das Denken ist eigentlich erst aufgekommen. Vor dem Saturn, der mit dem Denkorgan zusammenhängt, haben die alten Menschen immer einen heillosen Respekt gehabt. Der Saturn, haben sie sich gedacht, der verdirbt den Menschen. Zuviel denken, das geht nicht. Der Saturn hat immer als ein finsterer Planet gegolten. Und die Kräfte, die von dem Saturn gekommen sind, von denen dachten sie, wenn die zu stark im Menschen sind, wird er ganz melancholisch. Er denkt immerfort und wird melancholisch. Also die Saturnkräfte, die hatten diese Leute gar nicht besonders gern, und sie stellten viel mehr in Bildern vor. Sie rechneten weniger. Heute rechnen wir ja alles aus. Dieses ganze Weltenbild hier von Kopernikus ist ja berechnet. Diese alten Menschen rechneten aber nicht. Aber diese alten Menschen wußten etwas anderes, was der heutige Mensch nicht weiß. Sie wußten, überall in der Welt, wo wir hinschauen, sind viele Kräfte da. Aber die Kräfte, die im Menschen drinnen sind, die sind nicht in dem da, was man mit dem Auge sieht, sondern die sind im Unsichtbaren drinnen.

Und so hat sich Dante gesagt: Es gibt eine sichtbare Welt, und es gibt eine unsichtbare Welt. Die sichtbare Welt, nun ja, die ist diejenige, die wir sehen. Wenn wir hinausschauen in der Nacht, so sehen wir die Sterne, den Mond, die Venus und so weiter. Das ist die sichtbare Welt. Aber die unsichtbare Welt ist auch da. Und die unsichtbare Welt sind diese - man nannte das damals Sphären. Die unsichtbare Welt, das sind diese Sphären. Und man unterschied zwischen derjenigen Welt, die man mit Augen sieht, und nannte diese die physische Welt. Das war die physische Welt. Und dann unterschied man diejenige Welt, die man nicht mit Augen sieht. Das ist die Welt, die Dante gemeint hat, und die nannte man die ätherische Welt. Also die ätherische Welt, die Welt, die aus einem so feinen Stoff besteht, daß man fortwährend durchschaut.

Ja, meine Herren, ich weiß nicht, ob es Ihnen auch schon so gegangen ist, aber ich habe Leute kennengelernt, die haben behauptet, daß es keine Luft gibt, weil man sie nicht sieht. Die haben gesagt: Ja, wenn ich von da bis dort gehe, so ist doch nichts da; ich gehe doch da nicht durch etwas. — Sie wissen, daß da Luft ist, wo ich durchgehe. Aber, wie gesagt, ich habe schon Leute kennengelernt, die waren nicht so schulgebildet, wie die heutigen Menschen schulgebildet sind, und die haben nicht geglaubt, daß da Luft ist; die haben gesagt: Da ist doch nichts. - Dante, der wußte, daß wiederum nicht nur Luft ist, sondern Mond ist, Venus ist und so weiter. Es ist ganz dasselbe. Sie sagen: Ich gehe durch die Luft. Dante sagte: Ich gehe durch den Mond, ich gehe durch die Venus, ich gehe durch den Mars. — Das ist der ganze Unterschied. Und all das, was man nicht auf die gewöhnliche Weise sieht, und was man auch nicht wahrnehmen kann durch die gewöhnlichen physikalischen und chemischen Instrumente, das nannte man ätherische Welt. Also Dante schilderte eben eine ganz andere Welt, eine ätherische Welt. Und worauf beruht denn das also, daß vor sechs Jahrhunderten Dante die Welt anders gesehen hat? Das beruht darauf, daß er etwas anderes beschrieben hat, daß er das Unsichtbare beschrieben hat, die ätherische Welt. Und Kopernikus hat nichts anderes gesagt als: Ach, kümmern wir uns nicht um die ätherische Welt und beschreiben wir die physische Welt. Darinnen besteht der Fortschritt. — Man darf sich also nicht vorstellen, daß Dante ein «dummer August» gewesen ist, sondern er hat einfach die ätherische Welt beschrieben und nicht die physische. Die physische Welt war ihm nicht besonders wichtig. Er hat die ätherische Welt beschrieben.

Nun, sehen Sie, diese Sache hat sich im Grunde erst am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts wesentlich geändert. Bis zum Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts haben die Menschen immer noch etwas gewußt von dieser ätherischen Welt. Im 19. Jahrhundert haben sie nichts mehr von ihr gewußt. Wir kommen wiederum darauf durch die Anthroposophie. Im 19. Jahrhundert haben die Menschen nichts gewußt von dieser ätherischen Welt.

Zur anderen Frage:

Wenn wir ins 18. Jahrhundert zurückgehen, da hat man zum Beispiel folgendes gemacht. Da hat man gesagt: Hier haben wir eine Kerze; da ist der Docht; da brennt die Kerze. Nun wissen Sie ja, wenn die Kerze brennt, ist sie in der Mitte bläulich, am Rand gelblich. Das können Sie sich fein zurechtlegen durch das, was wir über die Farben gesagt haben. Nämlich, da in der Mitte, da ist es finster, und hell ist es hier (außen am Rande). Und die Folge davon ist, daß man das Finstere durch das Licht sieht. Und Sie wissen, das habe ich Ihnen neulich gesagt, wenn man das Finstere durch das Licht sieht, erscheint es blau.

Daher erscheint das Innere der brennenden Kerze blau, weil man da das Finstere durch das Licht sieht. Ich wollte Sie nur darauf aufmerksam machen, damit Sie sehen: die Farbgedanken, die Farbanschauungen, die ich Ihnen das letzte Mal gesagt habe, lassen sich auf alles an wenden. 77

Nun aber wissen Sie, wenn die Kerze brennt, wird sie immer weniger und weniger. Oben ist die Flamme, und in die Flamme geht dasjenige, was hier (an der Kerze) abschmilzt, über. Zuletzt ist die Kerze nicht mehr da. Das, was in der Kerze ist, das hat sich in die Luft verbreiter.

Denken Sie sich jetzt solch einen Menschen, sagen wir, im Jahre 1750, also vor noch nicht einmal zweihundert Jahren; der sagte: Ja, wenn da die Kerze verbrennt, und das alles in Luft aufgeht, dann geht etwas von der Kerze in den freien Raum hinaus. Zuletzt ist ja nichts mehr da. Es muß also die ganze Kerze in den freien Raum hinausgehen. Weiter sagte er: sie besteht aus ganz feinem Stoff, Feuerstoff. Dieser feine Feuerstoff verbindet sich mit der Flamme und geht nach allen Seiten heraus. So daß also der Mann im Jahre 1750 noch sagte: Da drinnen in diesem Wachs, da ist ein Stoff, der nur zusammengeschoppt ist, dicht gemacht ist. Wenn ihn die Flamme fein macht, geht er in den freien Raum hinaus. Diesen Stoff nannte man dazumal Phlogiston. Also es geht etwas von der Kerze fort. Der Feuerstoff, das Phlogiston geht fort von der Kerze.

Nun kam am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts ein anderer. Der sagte: Nein, die Geschichte glaube ich nicht recht, daß da ein Phlogiston ist, das in die Welt hinausgeht. Das glaube ich nicht! - Was hat er gemacht? Er hat folgendes gemacht. Er hat das Ganze auch verbrannt, aber er hat es so verbrannt, daß er alles, was sich da gebildet hat, aufgefangen hat. Er hat es in einem abgeschlossenen Raum verbrannt, so daß er alles das, was sich da bilden konnte, auffangen konnte. Und dann hat er es gewogen. Und dann hat er gefunden, daß das nicht leichter wird. Er hat also zuerst die ganze Kerze gewogen, und dann hat er das Stückchen, das noch geblieben ist, gewogen, wenn die Kerze bis dahin verbrannt ist (es wird gezeichnet); und dasjenige, was sich da beim Verbrennen gebildet hat, das hat er aufgefangen, hat es gewogen und hat gefunden, daß es dann etwas schwerer ist als vorher. Also, wenn etwas brennt, sagte er, dann wird dasjenige, was sich bildet, nicht leichter, sondern es wird schwerer.

Und dieser Mensch, der das gemacht hat, das war Lavoisier. Worauf beruhte denn also das, daß er eine ganz andere Ansicht bekam? Ja, das beruhte darauf, daß er zuerst die Waage anwendete, daß er alles wog. Und da sagte er: Wenn das schwerer ist, so muß nicht etwas weggegangen sein, muß nicht das Phlogiston weggegangen sein, sondern es muß etwas dazugekommen sein. Das ist der Sauerstoff, sagte er. Also man stellte sich vorher vor, daß das Phlogiston wegfliegt, und nachher stellte man sich vor, wenn etwas verbrennt, so dringt eigentlich der Sauerstoff herein, und die Verbrennung ist nicht die Zerstreuung von Phlogiston, sondern gerade die Anziehung von Sauerstoff. Das ist also dadurch gekommen, daß Lavoisier zuerst gewogen hat. Früher hat man nicht gewogen.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, da können Sie, ich möchte sagen, mit Händen greifen, was eigentlich geschehen ist. Am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts hat man nicht mehr an erwas geglaubt, was sich nicht wägen läßt. Natürlich, das Phlogiston kann man nicht wägen. Das Phlogiston geht schon fort. Der Sauerstoff kommt auch heran. Aber den Sauerstoff, wenn er sich verbindet, den kann man auch wiegen. Das Phlogiston, das kann man nicht auffangen. Warum? Ja, alles dasjenige, was Kopernikus am Mars und Jupiter beobachtet hat, das ist dasjenige, was schwer ist, wenn man es wiegt. Was Kopernikus den Mars nennt, das ist dasjenige, was, wenn man es auf eine große Waage legen würde, etwas wiegen würde. Ebenso, was er den Jupiter nennt. Er hat die schweren Körper bloß allein beguckt.

Dante hat nicht die schweren Körper bloß allein beguckt, sondern gerade dasjenige, was das Gegenteil hat von der Schwere, was immerzu fort will in den Weltenraum hinaus. Und das Phlogiston, das gehört einfach zu dem, was Dante beobachtet hat, und der Sauerstoff, der gehört zu dem, was Kopernikus beobachtet hat. Das Phlogiston ist das Unsichtbare, das sich zerstreut, der Äther. Der Sauerstoff ist ein Stoff, den man abwiegen kann.

So sehen Sie, wie der Materialismus entstanden ist. Das ist etwas, was Ihnen außerordentlich wichtig werden kann. Der Materialismus ist dadurch entstanden, daß man angefangen hat nur das zu glauben, was man wiegen kann. Nur kann man das, was Dante noch gesehen hat, eben nicht abwiegen. Wenn Sie hier auf der Erde herumgehen, kann man Sie auch abwiegen. Sie sind schwer, und wenn man bloß dasjenige, was schwer ist, Mensch nennt, dann hat man bloß den Erdenmenschen. Aber denken Sie sich, dieser Erdenmensch wird ein Leichnam. Alles Schwere, alles das, was man mit der Waage behandeln kann, wird ein Leichnam. Dann liegt der Leichnam da. Sie können dann immer noch leben in demjenigen, was nicht schwer ist, in demjenigen, was die Erde umgibt, und was der Materialismus ableugnet, wovon Dante noch spricht, wovon wir wieder sprechen müssen, daß es da ist. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn der Mensch seinen äußeren, schweren Leib, den man abwägen kann, ablegt, so bleibt er zunächst im Ätherleib zurück.

Nun will ich Ihnen aber sagen, was da eigentlich in diesem Ätherleib enthalten ist. Sehen Sie, wenn hier ein Stuhl ist, so kann ich diesen Stuhl sehen. Ich habe ein Bild in mir von diesem Stuhl. Doch wenn ich mich umdrehe, so sehe ich ihn nicht. Aber ich habe noch immer ein Bild von ihm drinnen in mir, richtig noch immer ein Bild. Dieses Bild ist das Erinnerungsbild.

Nun denken Sie an die Erinnerungsbilder. Denken Sie, Sie haben vor recht langer Zeit einmal etwas erlebt. Sie haben zum Beispiel erlebt, sagen wir, Sie waren irgendwo, haben auf einem Marktplatz lustige Menschen tanzen gesehen und so weiter. Ich könnte auch irgend etwas anderes nennen. Das Bild haben Sie behalten. Das ist ja nicht mehr da, meine Herren, was Sie da als Bild haben, namentlich nicht mehr da unter den Dingen, die man wiegen kann, die schwer sind, gar nirgends ist es mehr da. Nur in Ihnen kann es vorgestellt werden. Sie können heute herumgehen und können, wenn Sie eine lebhafte Phantasie haben, sich ganz gut vorstellen, wie das alles war, bis zu den Farben derjenigen, die da herumgesprungen sind. Sie haben das ganze Bild vor sich. Aber Sie werden keinen Augenblick daran denken, daß man das wiegen kann, was Sie damals gesehen haben. Das hier können Sie auf eine Waage legen. Die einzelnen Menschen sind schwer. Dasjenige, was Sie heute in sich tragen als Erinnerungsbilder, das können Sie nicht auf die Waage legen. Das gibt es nicht. Das ist geblieben, ohne daß die Sache selbst physisch noch da ist. Wie steckt denn das in Ihnen, was das Erinnerungsbild ist? Das steckt in Ihnen ätherisch. Nicht mehr physisch, sondern ätherisch steckt es in Ihnen.

Nun denken Sie sich einmal, Sie schwimmen, und durch irgendeinen Unglücksfall sind Sie nahe am Ertrinken; aber Sie werden gerettet. Solche Leute, die nahe am Ertrinken waren, und die gerettet worden sind, die haben zumeist von einem sehr interessanten Erinnerungsbild erzählt. Dieses Erinnerungsbild kann man dann ebenso wieder haben, wenn man nicht am Ertrinken ist, sondern wenn man sich geisteswissenschaftlich, anthroposophisch ausbildet. Diejenigen nämlich, die dem Ertrinken nahe waren, die haben einen Überblick über ihr ganzes irdisches Leben bis in die Kindheit. Es steigt alles auf. Auf einmal ist ein Erinnerungsbild da. Warum? Ja, meine Herren, weil der physische Leib, der jetzt im Wasser ist, etwas ganz Besonderes durchmacht. Und da müssen Sie sich an etwas erinnern, was ich Ihnen seinerzeit einmal gesagt habe. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt: Wenn man da hier Wasser hat und darinnen einen Körper, so wird der Körper im Wasser leichter. Er verliert von seinem Gewicht so viel, wie das Wasser wiegt, das als wässeriger Körper gerade so groß ist wie er selber.

Das ist eine schöne Geschichte, wie das entdeckt worden ist. Es ist schon im alten Griechenland entdeckt worden, daß jeder Körper im Wasser leichter wird. Archimedes hat viel nachgedacht über solche Dinge. Und einmal war Archimedes im Bade. Die Leute waren höchst erstaunt — ja, in Griechenland hat man so gebadet, daß die anderen es auch gesehen haben; es war übrigens auf Sizilien, das dazumal zu Griechenland gehörte -, die Leute waren höchst erstaunt, als Archimedes plötzlich aus dem Bad sprang und schrie: Heureka! Heureka! Heureka! Das heißt: Ich hab’s gefunden! — Die Leute dachten: Was hat denn der im Bad gefunden? Er war nämlich im Bad drinnen bis zum Kopf untergetaucht, hatte ein Bein herausgestreckt aus dem Wasser, und da hat er gefunden: Wenn er ein Bein aus dem Wasser herausnimmt, wird es schwerer; wenn er es wiederum herunternimmt, wird es wieder leichter. Da hat er zum ersten Mal gefunden im Bade, daß jeder Körper leichter wird, wenn er im Wasser ist. Das ist das sogenannte Archimedische Prinzip. Also jeder Körper ist leichter, wenn er im Wasser ist. Also auch, wenn einer ertrinkt, so wird sein physischer Körper leichter, sehr leicht. Nun kann noch immer, was er im Ätherkörper hat, sich halten, und da gehen ihm die ganzen Erinnerungen auf. Und sehen Sie, da gehen die Erinnerungen aus dem Grunde auf, weil er nicht mehr so schwer ist. Wenn der Mensch nun, wenn er stirbt, ganz draußen ist aus seinem physischen Körper, aus seinem physischen Leib, so ist er ganz leicht. Da lebt er ganz und gar in der Äthersphäre. Und da hat der Mensch nach seinem Tode jedesmal eine vollständige Erinnerung an das, was er auf der Erde erlebt hat bis zur Kindheit. Das ist das erste Erlebnis, das man nach dem Tode hat: eine vollständige Erinnerung.

Diese Erinnerung, die kann man prüfen. Nämlich die kann man so prüfen, daß man sich auf die Weise, wie ich das beschrieben habe in meinem Buche: «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» ausbildet. Dann kann man diese Erinnerung immer haben. Dann weiß man, daß die Seele unabhängig wird vom Leibe. Da bekommt sie zunächst diese Erinnerung, denn sie lebt zunächst nicht in demjenigen Stoff, den man ablegen kann, sondern, im Gegenteil, der hinaus will in alle Welt. Das ist der erste Zustand nach dem Tode. Da erinnert man sich. Den zweiten Zustand, den möchte ich Ihnen das nächste Mal beschreiben. Jetzt will ich aber etwas, was uns vorbereitet, beschreiben. Denn die Frage, die gestellt worden ist, ist eine furchtbar schwerwiegende.

Wenn man sich vorstellt, daß Dante sich über die Welt etwas vorgestellt hat, was die heutigen Menschen für eine Kinderei halten, dann ist nämlich das, was er sich weiter vorstellt, erst recht eine Kinderei für die heutigen Menschen. Wenn nämlich da auf der Erde (es wird gezeichnet) ein Mensch steht für Dante, dann stellt sich Dante vor: Hier in der Erde, abgewendet — also wenn man da durchgeht -, so würde man da in der Erde drinnen das haben, was er sich als Hölle vorstellt, Also er denkt sich: Da draußen, da ist überall Himmelsäther. Aber wenn ich hineinbohren würde in die Erde, da ist auf der andern Seite da die Hölle. Bevor ich aus der Erde herauskomme, ist da die Hölle.

Nun, dieses als kindisch aufzufassen, das wird ja dem heutigen Menschen furchtbar leicht. Man braucht nur zu sagen: Ja, aber Dante hätte nicht da zu stehen brauchen, sondern hier, dann hätte er da hineinbohren können, und dann wäre da (auf der andern Seite) die Hölle gewesen! - Natürlich, das kann der heutige Mensch sagen, weil der heutige Mensch weiß, auf der andern Seite leben auch Leute. Also kann er sehr leicht sagen: Ja, Dante war halt dumm; der hat noch durchaus nicht einsehen können, daß die Erde auf allen Seiten Menschen hat, und daß daher ebensogut hier die Hölle sein könnte wie dort. Denn der, der da steht, der kriegt nun den Himmel von der Seite, und für ihn wäre dann auf der andern Seite die Hölle.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, das ist so. Für die physische Welt kann es nur so sein: Wenn da der Himmel wäre, so könnte die Hölle nur hier sein; für die physische Welt könnte es nur so sein. Wenn ein Stuhl irgendwo steht, so kann er eben nur da stehen. Es gibt keinen zweiten Ort, wo er noch sein könnte.

Aber so hat es sich Dante nicht vorgestellt. Er hat überhaupt nicht die physische Welt vorgestellt, sondern er hat sich Kräfte vorgestellt. Und er hat gesagt: Ja, wenn ein Mensch da steht, und er bewegt sich mit seinem eigenen Ätherleib in der Richtung nach oben, dann wird er immer leichter und leichter. Dann überwindet er immer mehr die Schwere. Wenn er aber hineingeht in die Erde, da muß er sich immer mehr und mehr anstrengen, und diese Anstrengung wird am größten, wenn er zum andern Ende gekommen ist. Da preßt ihn alles. Da wird die Schwere am allergrößten. Das hängt nicht davon ab, daß dort irgendeine besondere Hölle ist, sondern daß er erst das durchgemacht hat, um dorthin zu kommen. (Zeichnung auf Seite 73.)

Und wenn sich Dante das so vorgestellt hat, so könnte er ja auch da stehen (am andern Ende). Wenn er sich da hinausbewegt, wird er immer leichter und leichter, kommt er immer mehr und mehr in den Äther hinein. Wenn er sich aber da hineinbewegt in die Erde, dann muß er das durchmachen (das Schwererwerden). Dann tritt für ihn der Zustand, das Erlebnis da ein, wo ich grün gezeichnet habe; früher aber da, wo ich gelb gezeichnet habe. Also darauf kommt es an. Dante sagt nicht, daß hier an diesem Ort gerade die Hölle ist, sondern Dante will sagen: Wenn einer durch die Erde sich durcharbeiten muß mit seinem Ätherleib, dann ist das so schwer, daß, wo er auch hinkommt, ob oben oder unten, für ihn ein Erlebnis eintritt, das höllisch ist. Das ist erst wiederum in der neuesten Zeit gekommen, daß sich die Leute die Hölle vorstellen an einem bestimmten Ort. Dante hat an das Erlebnis gedacht, das man bekommt, wenn man sich als Äthermensch durch die Erde durcharbeiten muß.

Wenn einer sagt: Dante war dumm -, so fällt das auf ihn selbst zurück, weil er so dumm ist und sagt, Dante hätte sich vorgestellt, daß die Hölle am andern Ende der Erde sei. Sondern Dante hat sich vorgestellt: Wo ich auch immer über die Erde in den Himmel hinausfliege, werde ich seelisch leichter; wo ich in die Erde hineinkomme, wo ich auch immer ans andere Ende komme: höllisch.

Also die ganze Vorstellung wurde eine andere. Und dann erst, wenn Sie ein wenig Rücksicht nehmen können auf die ganz andere Art, wie sich die Menschen das vorgestellt haben, dann können Sie auch das einsehen, was ich Ihnen das nächste Mal beantworten werde: Was bleibt von dem irdischen Menschen zurück, wenn er durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist?

Wenn es heute etwas schwerer war als sonst, so müssen Sie darauf Rücksicht nehmen, daß dies an der Frage liegt. Ich hoffe, daß es ein bißchen klarer geworden ist. Wir wollen dann am Samstag weiterkommen und den Menschen betrachten, wenn er durch den Tod geht, und was dann mit ihm wird.