Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

Discussion Two

22 August 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

A report was presented on the following questions: How is the sanguine temperament expressed in a child? How should it be treated?

RUDOLF STEINER: This is where our work of individuating begins. We have said that we can group children according to temperament. In the larger groups children can all take part in the general drawing lesson, but by dividing them into smaller groups we can personalize to some extent. How is this individuating to be done? Copying will play a very small part, but in drawing you will try to awaken an inner feeling for form so that you can individuate. You will be able to differentiate by your choice of forms by taking either forms with straight lines or those with more movement in them—by taking simpler, clearer forms, or those with more detail. The more complicated, detailed forms would be used with the child whose temperament is sanguine. From the various temperaments you can learn how to teach each individual child.

A report was given on the same theme.

RUDOLF STEINER: We must also be very clear that there is no need to make our methods rigidly uniform, because, of course, one teacher can do something that is very good in a particular case, and another teacher something else equally good. So we need not strive for pedantic uniformity, but on the other hand we must adhere to certain important principles, which must be thoroughly comprehended.

The question about whether a sanguine child is difficult or easy to handle is very important. You must form your own opinion about this and you must be very clear. For example, suppose you have to teach or explain something to a sanguine child. The child has taken it in, but after some time you notice that the child has lost interest—attention has turned to something else. In this way the child’s progress is hindered. What would you do if you noticed, when you were talking about a horse, for example, that after awhile the sanguine child was far away from the subject and was paying attention to something entirely different, so that everything you were saying passed unnoticed? What would you do with a child like this?

In such a case much depends on whether or not you can give individual treatment. In a large class many of your guiding principles will be difficult to carry out. But you will have the sanguine children together in a group, and then you must work on them by showing them the melancholic pattern. If there is something wrong in the sanguine group, turn to the melancholic group and then bring the melancholic temperament into play so that it acts as an antidote to the other. In teaching large numbers you must pay great attention to this. It’s important that you should not only be serious and restful in yourself, but that you should also allow the serious restfulness of the melancholic children to act on the sanguine children, and vice versa.

Let’s suppose you are talking about a horse, and you notice that a child in the sanguine group has not been paying attention for a long time. Now try to verify this by asking the child a question that will make the lack of attention apparent. Then try to verify that one of the children in the melancholic group is still thinking about some piece of furniture you were talking about quite awhile ago, even though you have been speaking about the horse during that time. Make this clear by saying to the sanguine child, “You see, you forgot the horse a long time ago, but your friend over there is still thinking about that piece of furniture!”

A real situation of this kind works very strongly. In this way children act correctively on each other. It is very effective when they come to see themselves through these means. The subconscious soul has a strong feeling that such lack of cooperation will prevent a continuation of social life. You must make good use of this unconscious element in the soul, because teaching large numbers of children can be an excellent way to progress if you let your pupils wear off each other’s corners. To bring out the contrast you must have a very light touch and humor, so that the children see you are never annoyed nor bear a grudge against them—that things are revealed simply through your method of handling them.

The phlegmatic child was spoken of.

RUDOLF STEINER: What would you do if a phlegmatic child simply did not come out of herself or himself at all and nearly drove you to despair?

Suggestions were presented for the treatment of temperaments from the musical perspective and by relating them to Bible history.

Phlegmatics: Harmonium and piano; Harmony; Choral singing; The Gospel of Matthew; (variety)

Sanguines: Wind instruments; Melody; Whole orchestra; The Gospel of Luke; (Inwardness of soul)

Cholerics: Percussion and drum; Rhythm; Solo instruments; The Gospel of St. Mark; (Force, strength) Melancholics: Stringed Instruments; Counterpoint; Solo singing; The Gospel of St. John; (Deepening of the spirit)

RUDOLF STEINER: Much of this is very correct, especially the choice of instruments and musical instruction. Equally good is the contrast of solo singing for the melancholic, the whole orchestra for the sanguine, and choral singing for the phlegmatic. All this is very good, and also the way you have related the temperaments to the four Evangelists. But it wouldn’t be as good to delegate the four arts according to temperaments; it is precisely because art is multifaceted that any single art can bring harmony to each temperament.1 The teacher who presented the above suggestions had also allocated particular arts to the various temperaments. Within each art the principle is correct, but I would not distribute the arts themselves in this way. For example, you could in some circumstances help a phlegmatic child very much through something that appeals to the child in dancing or painting. Thus the child would not be deprived of whatever might be useful in any of the various arts. In any single art it is possible to allocate the various branches and expressions of the art according to temperament. Whereas it is certainly necessary to prepare everything in the best way for individual children, it would not be good here to give too much consideration to the temperaments.

An account was given about the phlegmatic temperament and it was stated that the phlegmatic child sits with an open mouth.

RUDOLF STEINER: That is incorrect; the phlegmatic child will not sit with the mouth open but with a closed mouth and drooping lips. Through this kind of hint we can sometimes hit the nail on the head. It was very good that you touched on this, but as a rule it is not true that a phlegmatic child will sit with an open mouth, but just the opposite. This leads us back to the question of what to do with the phlegmatic child who is nearly driving us to despair. The ideal remedy would be to ask the mother to wake the child every day at least an hour earlier than the child prefers, and during this time (which you really take from the child’s sleep) keep the child busy with all kinds of things. This will not hurt the child, who usually sleeps much longer than necessary anyway. Provide things to do from the time of waking up until the usual waking hour. That would be an ideal cure. In this way, you can overcome much of the child’s phlegmatic qualities. It will not be possible very often to get parents to cooperate in this way, but much could be accomplished by carrying out such a plan.

You can however do the following, which is only a substitute but can help greatly. When your group of phlegmatics sit there (not with open mouths), and you go past their desks as you often do, you could do something like this: [Dr. Steiner jangled a bunch of keys]. This will jar them and wake them up. Their closed mouths would then open, and exactly at this moment when you have surprised them, you must try to occupy them for five minutes! You must rouse them, shake them out of their lethargy by some external means. By working on the unconscious you must combat this irregular connection between the etheric and physical bodies. You must continually find fresh ways to jolt the phlegmatics, thus changing their drooping lips to open mouths, and that means that you will be making them do just what they do not like doing. This is the answer when the phlegmatics drive you to despair, and if you keep trying patiently to shake up the phlegmatic group in this way, again and again, you will accomplish much.

Question: Wouldn’t it be possible to have the phlegmatic children come to school an hour earlier?

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, if you could do that, and also see that the children are wakened with some kind of noise, that would naturally be very good; it would be good to include the phlegmatic children among those who come earliest to school.2This refers to the need for having school in shifts. The important thing with the phlegmatic children is to engage their attention as soon as you have changed their soul mood.

The subject of food in relation to the different temperaments was introduced.

RUDOLF STEINER: On the whole, the main time for digestion should not be during school hours, but smaller meals would be insignificant; on the contrary, if the children have had their breakfast they can be more attentive than when they come to school on empty stomachs. If they eat too much—and this applies especially to phlegmatic children—you cannot teach them anything. Sanguine children should not be given too much meat, nor phlegmatic too many eggs. The melancholic children, on the other hand, can have a good mixed diet, but not too many roots or too much cabbage. For melancholic children diet is very individual, and you have to watch that. With sanguine and phlegmatic children it is possible to generalize.

The melancholic temperament was spoken of.

RUDOLF STEINER: That was very good. When you teach you will also have to realize that melancholic children get left behind easily; they do not keep up easily with others. I ask you to remember this also.

The same theme was continued.

RUDOLF STEINER: It was excellent that you stressed the importance of the teacher’s attitude toward the melancholic children. Moreover, they are slow in the birth of the etheric body, which otherwise becomes free during the change of teeth. Therefore, these children have a greater aptitude for imitation; if they have become fond of you, everything you do in front of them will make a lasting impression on them. You must use the fact that they retain the principle of imitation longer than others.

A further report on the melancholic temperament.

RUDOLF STEINER: You will find it very difficult to treat the melancholic temperament if you fail to consider one thing that is almost always present: the melancholic lives in a strange condition of self-deception. Melancholics have the opinion that their experiences are peculiar to themselves. The moment you can bring home to them that others also have these or similar experiences, they will to some degree be cured, because they then perceive they are not the singularly interesting people they thought themselves to be. They are prepossessed by the illusion that they are very exceptional as they are.

When you can impress a melancholic child by saying, “Come on now, you’re not so extraordinary after all; there are plenty of people like you, who have had similar experiences,” then this will act as a very strong corrective to the impulses that lead to melancholy. Because of this it is good to make a point of presenting them with the biographies of great persons; they will be more interested in these individuals than in external nature. Such biographies should be used especially to help these children over their melancholy.

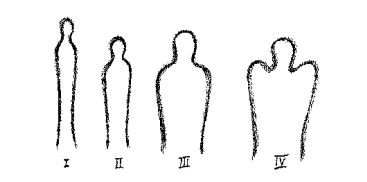

Two teachers spoke about the choleric temperament. Rudolf Steiner then drew the following figures on the board:

What do we see in these figures? They depict another characterization of the four temperaments. The melancholic children are as a rule tall and slender; the sanguine are the most normal; those with more protruding shoulders are the phlegmatic children; and those with a short stout build so that the head almost sinks down into the body are choleric.

Both Michelangelo and Beethoven have a combination of melancholic and choleric temperaments. Please remember particularly that when we are dealing with the temperament of a child, as teachers we should not assume that a certain temperament is a fault to be overcome. We must recognize the temperament and ask ourselves the following question: How should we treat it so that the child may reach the desired goal in life—so that the very best may be drawn out of the temperament and with the help of their own temperaments, children can reach their goals.

Particularly in the case of the choleric temperament, we would help very little by trying to drive it out and replacing it with something else. Indeed, much arises from the life and passion of choleric people—especially when we look at history and find that many things would have happened differently had there been no cholerics. So we must make it our task to bring the child, regardless of the temperament, to the goal in life belonging to that child’s nature.

For the choleric you should use as much as possible fictional situations, describing situations you have made up for the occasion, and that you bring to the child’s attention. If, for example, you have a child with a temper, describe such situations to the child and deal with them yourself, treating them in a choleric way. For example, I would tell a choleric child about a wild fellow whom I had met, whom I would then graphically describe to the child. I would get roused and excited about him, describing how I treated him, and what I thought of him, so that the child sees temper in someone else, in a fictitious way the child sees it in action. In this way you will bring together the inner forces of such a child, whose general power of understanding is thus increased.

The teachers asked Rudolf Steiner to relate the scene between Napoleon and his secretary.

Rudolf Steiner: For this you would first have to get permission from the Ministry of Housing! Through describing such a scene the choleric element would have to be brought out. But a scene such as I just mentioned must be described by the teacher so that the choleric element is apparent. This will always arouse the forces of a choleric child, with whom you can then continue to work. It would be ideal to describe such a situation to the choleric group in order to arouse their forces, the effect of which would then last a few days. During that few days the children will have no difficulty taking in what you want to teach them. Otherwise they fume inwardly against things that they should be getting through their understanding.

Now I would like you to try something: we should have a record of what we have been saying about the treatment of temperaments, and so I should like to ask Miss B. to write a comprehensive survey (approximately six pages) of the characteristics of the different temperaments and how to treat them, based on everything I have spoken about here. Also, I will ask Mrs. E. to imagine she has two groups of children in front of her, sanguine and melancholic and then, in a kind of drawing lesson, to use simple designs, varied according to sanguine and melancholic children. I will ask Mr. T. to do the same thing with drawings for phlegmatic and choleric children; and please bring these tomorrow when you have prepared them.

Then I will ask, let us say, Miss A., Miss D., and Mr. R. to deal with a problem: Imagine that you have to tell the same fairy tale twice—not twice in the same way, but clothed in different sentences, and so on. The first time pay more attention to the sanguine and the second time to the melancholic children, so that both get something from it.

Then I ask that perhaps Mr. M. and Mr. L. work at the difficult task of giving two separate descriptions of an animal or animal species, first for the cholerics and then for the phlegmatics. And I will ask Mr. O., Mr. N., and perhaps with the help of Mr. U. to solve the problem of how to consider the four temperaments in arithmetic.

When you consider something like the temperaments in working out your lessons, you must remember above all that the human being is constantly becoming, always changing and developing. This is something that we as teachers must have always in our consciousness—that the human being is constantly becoming, that in the course of life human beings are subject to metamorphosis. And just as we should give serious consideration to the temperamental dispositions of individual children, so we must also reflect on the element of growth, this becoming, so that we come to see that all children are primarily sanguine, even if they are also phlegmatic or choleric in certain things. All adolescents, boys and girls, are really cholerics, and if this is not so at this time of life it shows an unhealthy development. In mature life a person is melancholic and in old age phlegmatic.

This again sheds some light on the question of temperaments, because here you have something particularly necessary to remember at the present time. In our day we love to make fixed, sharply defined concepts. In reality, however, everything is interwoven so that, even while you are saying that a person is made up of head, breast, and limb organizations, you must be clear that these three really interpenetrate one another. Thus a choleric child is only mostly choleric, a sanguine mostly sanguine, and so on. Only at the age of adolescence can one become completely choleric. Some people remain adolescents till they die, because they preserve this age of adolescence within themselves throughout life. Nero and Napoleon never outgrew the age of youth. This shows us how qualities that follow each other during growth can still—through further change—permeate each other again.

What is the poet’s productivity actually based on—or indeed any spiritually creative power? How does it happen that a man, for example, can become a poet? It is because he has preserved throughout his whole life certain qualities that belonged to early manhood and childhood. The more such a man remains “young,” the more aptitude he has for the art of poetry. In a certain sense it is a misfortune for such a man if he cannot keep some of the qualities of youth, something of a sanguine nature, his whole life through. It is very important that teachers can become sanguine out of their own resolve. And it is moreover tremendously important for teachers to remember this so they may cherish this happy disposition of the child as something of particular value.

All creative qualities in life—everything that fosters the spiritual and cultural side of the social organism—all of this depends on the youthful qualities in a human being. These things will be accomplished by those who have preserved the temperament of youth. All economic life, on the other hand, depends on the qualities of old age finding their way into people, even when they are young. This is because all economic judgment depends on experience. Experience is best gained when certain qualities of old age enter into people, and the old person is indeed a phlegmatic. Those business people prosper most whose other attributes and qualities have an added touch of the phlegmatic, which really already bears the stamp of old age. That is the secret of very many business people—that in addition to their other good qualities as business people, they also have something of old age about them, especially in the way they manage their businesses. In the business world, a person who only developed the sanguine temperament would only get as far as the projects of youth, which are never finished. A choleric who remains at the stage of youth might spoil what was done earlier in life through policies adopted later. The melancholic cannot be a business person anyway, because a harmonious development in business life is connected with a quality of old age. A harmonious temperament, along with some of the phlegmatic’s unexcitability is the best combination for business life.

You see, if you are thinking of the future of humankind you must really notice such things and consider them. A person of thirty who is a poet or painter is also something more than “a person of thirty,” because that individual at the same time has the qualities of childhood and youth within, which have found their way into the person’s being. When people are creative you can see how another being lives in them, in which they have remained more or less childlike, in which the essence of childhood still dwells. Everything I have exemplified must become the subject of a new kind of psychology.