The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

30 March 1919, Dornach

Automated Translation

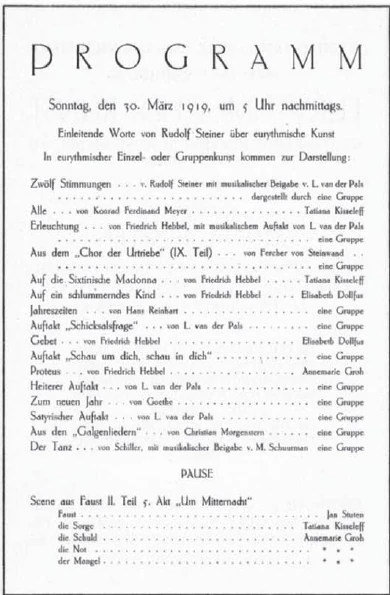

10. Eurythmy Performance

Dear attendees! Please allow me to say a few words before our eurythmy performance. I feel this is all the more justified as this performance will be about an experiment, or perhaps I could say: the intention of an experiment. For it is tempting to compare what we will be offering as a movement art with all kinds of neighboring arts, dance arts and the like, and [it is tempting] to think that we want to compete with such neighboring arts. Now we know very well that what is being achieved today in the various neighboring arts is something extraordinarily perfect in its own right. And we would be completely misunderstood if it were thought that we want to compete with it in any way. What we want is something quite different: to create an art of movement in its own right, which is admittedly only at the beginning. And that is what I would particularly like to emphasize: that we think very modestly about this particular stage at which we still stand today with regard to this our special, unique art form, and in this sense I also ask you to accept our presentation today.

What we are attempting has a completely different source from neighboring arts. It comes from the same source from which everything that is done here in this Goetheanum should flow: It comes from Goethe's world view and view of art. Even if we are striving to carry out a 20th-century Goetheanism, that is, one that has been further developed in line with the views of modern times, it is still from the source of Goethe's world and art view that we draw.

Perhaps I can best suggest what needs to be said about our art of movement by pointing to a certain branch of Goethe's vast and comprehensive world view, to his view of nature. Goethe himself sought the sources of his artistic vision in his intense, intuitive view of nature. He coined the beautiful phrase: When nature begins to reveal its secrets to someone, that person feels the most ardent longing for its most worthy interpreter, art. It may seem as though I am taking you on a brief journey to a remote theoretical area of Goethe's work, to the area of Goethe's theory of metamorphosis. For that which was expressed in the comprehensive view of the metamorphosis of living beings can be completely translated into artistic form. Goethe saw in every single plant leaf a whole plant, only in a simple form, developed in the leaf, and he saw in turn in every single part of the plant a transformed leaf. In the colorful blossom, he saw transformed leaves; yes, even in the stamens and pistils, which in their external form look so little like leaves, Goethe saw transformed, metamorphosed plant leaves. And the whole plant was in turn an intricately designed leaf for him. Goethe applied this view to all of nature. And we can only come to terms with living nature if we base our understanding of it on this kind of view, right up to the human being, if we follow how everything consists of living members that are actually only repetitions of the whole, of the whole organism, how the whole organism is only a complicated elaboration, transformation of the individual member. This can also be applied by progressing to the most complicated natural phenomenon, to man, and not only to the forms of his individual limbs, but it can also be applied to the activity of the human organism.

In so far as we have the natural human organization, we carry the larynx and its neighboring organs within us. Through this larynx and its neighboring organs, we produce that which not only functions as speech from person to person, but which can be artistically developed in poetic and artistic language, in song, and in the element of music. If we are able to follow, through intuitive observation, through spiritual observation, the movement patterns that are present in the larynx itself, we can say that what goes on in the movements of this single human limb, in the larynx, when we speak or sing artistically, can be transformed into activity, into movement of the whole human being. The whole human being can become like a visible larynx. We could also say that when we speak, that is, when we add sound to sound or tone to tone in a logical way, the air moves in certain rhythmic movements. These rhythmic movements are not what we can turn our attention to when we listen while speaking. But intuitive insight can form a picture of what is actually going on invisibly in the air movement. And all of this can be transferred to movements of the whole human being.

Dear ladies and gentlemen, our eurythmic art is based on this, which, as I said, is only an experiment today. The whole human being, as he presents himself to you here on the stage, should act like a living larynx. Of course, this must be further expanded. When we speak artistically, when we make language the organ of poetry, when we make it the organ of music, the warmth of inner feeling resonates through the sound, and the lawful sequence of sounds, tones, moods, resonates within. That which resonates in human speech and in poetry in terms of feeling, mood, emotional content, and inner soul movement, in terms of rhyme, rhythm, alliteration, and assonance, should in turn be expressed in the positions and movements of groups of people performing eurythmy.

Thus everything that is otherwise revealed to the human ear in sound is to be expressed through such an art of movement. I am not saying that one must always recognize how something inward is expressed through one or other movement of the person or the group. Of course, once such an artistic source, to which I have just referred, has been found, what can then be represented through it must have an immediate artistic effect on intuitive perception. It will do so if it is developed to a certain degree of artistic perfection. For art – as Goethe says so beautifully – is based on a manifestation, on a revelation of certain natural laws that would never be revealed without it. So the person who discovers secret natural laws through intuitive contemplation and transforms them into something visible is walking the path of how art can truly be brought about. For in the truly artistic, in that which is not merely artistic in a naturalistic or external sense, in the truly artistic one must always have the sensation of looking intensely into an infinite and ever more infinite, into an abyssal depth. This is only possible if what is presented artistically is taken from the inner laws of nature itself. This is what has been attempted here. Therefore, what is presented visually for direct contemplation must also appear artistic. Goethe says so beautifully that art is based on the depths of knowledge, on the essence of things, insofar as we are allowed to express this essence of things in visible or tangible forms.

In this sense, the eurythmy art aspires to achieve something Goethean.

Only then will one understand what is actually intended by it in the right way, if one does not compare it at all, this our eurythmic art, with what is attempted as a dance art or the like in pantomime or through gestures or through a direct, instantaneous connection between movements and inner soul emotions. What is intended in our eurythmy is like the musical element itself. Just as the musical element is based on an inner, objective law in harmony and melody, so what is presented in eurythmy is based on such a law - not on the momentary will of a movement to interact with the inner soul life. Therefore, in this eurythmy too, there is no arbitrariness, no momentary connection sought between a gesture and the inner soul movement. When two people perform something for you in eurythmy, the diversity is no different from the diversity that exists when two pianists perform a Beethoven sonata with a different subjective interpretation. What matters to us is the continuity of the inner lawfulness, not the eliciting of a momentary gesture from the person. Therefore, all pantomime, all mime, all momentary gestures, all that is eliminated. And where they will still be noticed in our performing art, it is only because in the beginning things are still imperfect. It will be eliminated in the course of the development of this particular art form.Thus, if one enters into what this art is about – as we have once set it up – on the one hand one can see the human larynx embodied in the movements and forms of the whole person and groups of people, and on the other hand one can hear the poetry and the music, so that the two complement each other and unite to form a total work of art. And it should be understood, esteemed attendees, that the recitation that accompanies the eurythmic art must be held differently than what is usually understood by recitation today, precisely because it appears as a special artistic supplement to eurythmy.

Recitation today has actually stepped out of the realm of the truly artistic. Recitation today is actually limited to the presentation of the poetic content. The discovery of an art form such as that on which eurythmy is based will in turn lead to recitation itself being restored to what it once was, something that those who are younger today no longer know. Those who are older today can still remember the reciters of the 70s and 80s, who perhaps already belonged to the decadent, but still offered an echo of what the art of recitation used to be. Few people today know that Goethe rehearsed “Iphigenia” for the stage in Weimar, conducting with a baton like a musical work of art. The aim was to make the rhythmical and the artistic audible. This art of recitation has been lost. Through eurythmy, it will in a sense become necessary again. Today, people no longer want to hear what is actually poetic and artistic: it is the poetic form, not what can be expressed by summarizing the content. Basically, the art of recitation today is nothing more than a particularly sophisticated form of reading prose. And only by taking a detour through eurythmy will we be able to rediscover the art of recitation and declamation. This is not understood today.

So I would like to ask you, dear attendees, to take on board our presentation in the sense in which it has been presented, and above all to bear in mind that we ourselves – as I said at the beginning – think very modestly about what we are already able to achieve. If it is met with understanding, it will be able to develop further. And we are convinced that today we are still at the beginning of its development with this eurythmy. But we ourselves - or perhaps not we ourselves, but others - will be able to bring out of it something that can be placed alongside other art forms as a special new art form.

What will appear particularly important – because artistic creation has been elevated to the level of the human being – is what Goethe directly points out in his beautiful book about Winckelmann, in which he says: When the human being is placed at the summit of nature, he sees himself again as a whole nature and brings forth, takes harmony, proportion, meaning, significance and content together, in order to finally rise to the production of the work of art.

In eurythmy, something should be presented like a work of art that comes directly from what is possible in the human being in terms of movement and inner strength, to external revelation. I ask you to consider that a start has been made on this in our eurythmy. And in this sense, I ask you to take up our presentation and give it your indulgence and attention.

[After the break:]

In the second part, we will present the scene at midnight from Goethe's “Faust II”, the so-called “four gray women”: worry, guilt, lack, need.

It is the case that this scene in particular can be seen as a kind of rehearsal for our eurythmic art. It will be seen that from “Faust”, in which Goethe, as he himself said, so much has been secretly hidden, through eurythmy, something will be able to be brought out that has not yet been brought out by ordinary stage performance, - If one has often seen the representations of the first part of “Faust” - I will say: the representation for example, on the one hand, the [Devrient-Lassen] performance, then one has the feeling that it stylizes what Goethe not only in terms of content but also in terms of style, according to the higher art form, also incorporated into “Faust”, that it comes out in this way [mysteries]; [but] then the thing very easily becomes operatic. On the other hand, if you stick to acting – I remember Wilbrandt's performance, or others – it can easily happen that scenes that shine so deeply into the human soul as this scene of sorrow can remain empty and poor.

The way in which eurythmy expresses what Goethe so stylishly attempted to express in the second part of “Faust”, in this most mature of poems – this kind of eurythmic performance will be best suited to bringing out, perhaps through eurythmy, what Goethe meant. And that is why it will be possible to make just such an attempt at presenting this scene, to show how, with the help of eurythmy, a coherent whole can arise from these arts in addition to the acting.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Sehr verehrte Anwesende! Gestatten Sie, dass ich unserer Eurythmie-Aufführung einige Worte voranschicke. Es erscheint mir dieses umso mehr gerechtfertigt, als es sich bei dieser Vorstellung handeln wird um einen Versuch, vielleicht könnte ich sagen: um die Absicht eines Versuchs. Denn es liegt nahe, dasjenige, was wir als Bewegungskunst anbieten werden, zu vergleichen mit allerlei Nachbarkünsten, Tanzkünsten und dergleichen, und [es liegt nahe,] dass man glauben könnte, wir wollen mit solchen Nachbarkünsten konkurrieren. Nun wissen wir sehr wohl, dass dasjenige, was auf diesem Gebiete der verschiedenen Nachbarkünste heute geleistet wird, etwas außerordentlich Vollkommenes in seiner Art ist. Und man würde uns ganz missverstehen, wenn man glauben würde, dass wir damit in irgendeiner Beziehung konkurrieren wollen. Dasjenige, was wir wollen, ist etwas ganz anderes, will eine Bewegungskunst für sich sein, die allerdings vorläufig bloß in ihrem Anfange steht. Und das ist es, was ich besonders betonen möchte: Dass wir über diese besondere Stufe, auf der wir heute noch mit Bezug auf diese unsere besondere, eigenartige Kunstrichtung stehen, sehr bescheiden denken, und in diesem Sinne bitte ich Sie auch, unsere Darbietung heute hinzunehmen.

Dasjenige, was wir versuchen, kommt aus einer ganz anderen Quelle als die Nachbarkünste. Es kommt aus derselben Quelle, aus der alles dasjenige fließen soll, was hier in diesem Goetheanum getrieben wird: Es kommt aus der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung und Kunstanschauung. Wenn wir auch bestrebt sind, gewissermaßen einen Goetheanismus des 20. Jahrhunderts — das heißt einen solchen, der fortentwickelt ist gemäß den Anschauungen der neueren Zeit — auszuführen, so ist es doch eben die Quelle der Goethe’schen Welt- und Kunstanschauung, aus der wir schöpfen.

Dasjenige, was gerade mit Bezug auf diese unsere Bewegungskunst zu sagen ist, kann ich vielleicht am besten dadurch andeuten, dass ich auf einen gewissen Zweig der gewaltigen, großen Goethe’schen Weltanschauung hinweise, auf Goethes Naturanschauung. Goethe hat ja selbst die Quellen seiner Kunstanschauung in seiner eindringlichen, auf Intuition beruhenden Naturanschauung gesucht. Er hat das schöne Wort geprägt: Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis zu erschließen beginnt, der empfindet die lebhafteste Sehnsucht nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst. Nur scheinbar wird es sein, dass ich Sie mit ein paar Worten auf ein abgelegenes theoretisches Gebiet bei Goethe führe, auf das Gebiet der Goethe’schen Metamorphosenlehre. Denn dasjenige, was sich für ihn in der umfassenden Anschauung von der Metamorphose der lebenden Wesen ausprägte, das lässt sich ganz und gar in künstlerische Gestaltung umsetzen. Goethe sah in jedem einzelnen Pflanzenblatt eine ganze Pflanze, nur eben in einfacher Gestalt, im Blatte ausgebildet, und er sah wiederum in jedem einzelnen Gliede der Pflanze ein umgestaltetes Blatt. In der farbigen Blüte sah er umgestaltete Blätter; ja selbst in den Staubgefäßen und im Stempel, die in der äußeren Form so wenig ähnlich sehen den Blättern, sah Goethe umgeformte, metamorphosierte Pflanzenblätter. Und die ganze Pflanze war ihm wiederum ein kompliziert ausgestaltetes Blatt. Diese Anschauung wandte Goethe auf die ganze lebendige Natur an. Und man kommt mit der lebendigen Natur nur zurecht, wenn man zu ihrer Erkenntnis eine solche Anschauung zugrunde legt bis hinauf zum Menschen, wenn man verfolgt, wie alles lebendig aus Gliedern besteht, die eigentlich nur Wiederholungen des Ganzen sind, des ganzen Organismus sind, wie der ganze Organismus nur eine komplizierte Ausgestaltung, Umgestaltung des einzelnen Gliedes ist. Das kann man nun auch anwenden, indem man zum Menschen hinaufschreitet, auf die komplizierteste Naturerscheinung, auf den Menschen, und da nicht nur auf die Formen seiner einzelnen Glieder, sondern man kann es anwenden auf die Tätigkeit des menschlichen Organismus.

Wir tragen in uns, insofern wir die natürliche Menschenorganisation haben, den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane. Durch diesen Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane bringen wir hervor dasjenige, was nicht nur als Lautsprache von Mensch zu Mensch wirkt, sondern was künstlerisch durchgestaltet werden kann, in der dichterischen, in der künstlerischen Sprache durchgestaltet werden kann, im Gesang, im musikalischen Elemente. Wenn man nun durch intuitive Anschauung, durch geistige Anschauung dasjenige zu verfolgen in der Lage ist, was im Kehlkopf selber an Bewegungsanlagen vorhanden ist, so lässt sich das umsetzen so, dass man sagt: Was so in den Bewegungen dieses einzelnen menschlichen Gliedes, im Kehlkopf vor sich geht, wenn wir künstlerisch sprechen oder singen, das lässt sich umwandeln in Tätigkeit, in Bewegung des ganzen Menschen. Der ganze Mensch kann wie ein sichtbarer Kehlkopf werden. Man könnte auch so sagen: Indem wir sprechen, das heißt, Laut an Laut oder Ton an Ton gesetzmäßig anfügen, gerät die Luft in bestimmte rhythmische Bewegungen. Diese rhythmischen Bewegungen sind nicht das, auf was wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit wenden können, wenn wir bei dem Sprechen zuhören. Aber die intuitive Anschauung kann ein Bild bekommen von dem, was da eigentlich gewöhnlich unsichtbar in der Luftbewegung vor sich geht. Und das alles lässt sich übertragen auf Bewegungen des Gesamtmenschen.

Darauf, sehr verehrte Anwesende, beruht unsere eurythmische Kunst, die - wie gesagt - heute nur erst ein Versuch ist. Der ganze Mensch soll, wie er Ihnen hier auf der Bühne entgegentritt, wie ein lebendiger Kehlkopf wirken. Das muss natürlich weiter ausgedehnt werden. Indem wir künstlerisch sprechen, die Sprache zum Organ der Dichtkunst machen, zum Organ des Musikalischen machen, durchklingt innere Empfindungswärme den Ton, und die gesetzmäßige Tonfolge, Laut, Stimmung, klingt hinein. Dasjenige, was also hineinklingt an Empfindung, an Stimmung, an Gemütsinhalt, an innerer Seelenbewegung in das menschliche Sprechen und in der Dichtung an Reim, an Rhythmus, an Alliteration, an Assonanz, das soll wiederum ausgedrückt werden in Stellungen und Bewegungen der Gruppen von Menschen, welche die Eurythmie vorführen.

So soll alles dasjenige durch eine solche Bewegungskunst zur Darstellung kommen, was sonst für das menschliche Gehör in Laut, im Ton zur Offenbarung kommt. Nicht das behaupte ich, dass man immer erkennen muss, wie irgendetwas Inneres durch die eine oder andere Bewegung des Menschen oder der Gruppe zum Ausdruck kommt. Natürlich, indem eine solche Kunstquelle, auf die ich eben gedeutet habe, gefunden worden ist, muss dasjenige, was dann durch sie dargestellt werden kann, unmittelbar für die Anschauung künstlerisch wirken. Das wird es auch tun, wenn es bis zu einem gewissen Grade der künstlerischen Vollkommenheit ausgestaltet ist. Denn die Kunst - das sagt Goethe so schön — beruht auf einer Manifestation, auf einer Offenbarung gewisser Naturgesetze, die ohne sie niemals offenbar würden. Derjenige, der also durch intuitive Anschauung geheime Naturgesetze entdeckt und sie umsetzt in äußerlich Sichtbares, der wandert auf dem Wege, wie Künstlerisches wirklich hervorgebracht werden kann. Denn bei wahrhaft Künstlerischem, bei dem, was nicht bloß im naturalistischen oder im äußerlichen Sinne künstlerisch ist, bei dem wahrhaft Künstlerischen muss man stets die Empfindung haben, dass man intensiv in ein Unendliches und immer Unendlicheres, in ein Abgrundtiefes hineinschaut. Das kann man nur, wenn dasjenige, was künstlerisch dargeboten wird, aus der inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit der Natur selbst herausgeholt ist. Solches ist hier versucht. Deshalb muss auch dasjenige, was sich sichtbarlich darstellt unmittelbar für die Anschauung, kunstgemäß wirken. Goethe sagt wiederum so schön, die Kunst beruhe auf Tiefen der Erkenntnis, auf dem Wesen der Dinge, insofern es uns gestattet ist, dieses Wesen der Dinge in sichtbarlichen oder greifbaren Gestalten zum Ausdruck zu bringen.

In diesem Sinne ist Goethe’sches angestrebt durch die eurythmische Kunst. Nur dann wird man, was eigentlich mit ihr gewollt ist, in der richtigen Art verstehen, wenn man sie gar nicht vergleicht, diese unsere eurythmische Kunst, mit dem, was als Tanzkunst oder dergleichen pantomimisch oder durch Geste oder durch einen unmittelbaren, augenblicklichen Zusammenhang von Bewegungen und inneren Seelenemotionen darzustellen versucht wird. Dasjenige, was in unserer Eurythmie gewollt ist, ist wie das musikalische Element selbst. Wie das musikalische Element auf einer inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit, auf einer objektiven Gesetzmäßigkeit in Harmonie und Melodie beruht, so beruht auf einer solchen Gesetzmäßigkeit - nicht auf dem augenblicklichen Zusammenwirken-Wollen einer Bewegung mit dem inneren Seelenleben - dasjenige, was in der Eurythmie zur Darstellung kommt. Daher ist auch in dieser Eurythmie nicht Willkürliches, nicht ein augenblicklicher Zusammenhang gesucht zwischen einer Geste und der inneren Seelenbewegung. Wenn zwei Menschen Ihnen eurythmisch etwas darstellen, so ist das keine Verschiedenheit anders, als die Verschiedenheit besteht, wenn zwei Klavierspieler in einer verschiedenen subjektiven Auffassung eine Beethoven’sche Sonate darstellen. Auf die fortlaufende innere Gesetzmäßigkeit kommt es uns an, nicht auf das Herausholen einer Augenblicksgeste aus dem Menschen. Daher ist alles Pantomimische, alles Mimische, alle Augenblicksgeste, alles das ist ausgeschaltet. Und wo sie es doch noch bemerken werden in unserer darzustellenden Kunst, da rührt es nur her, weil im Anfange die Dinge noch unvollkommen [sind]. Es wird sich im Verlauf der Entwicklung dieser besonderen Kunstform schon ausschalten.

So kann man, wenn man auf dasjenige, was diese Kunst will, eingeht - so wie wir es einmal eingerichtet haben - auf der einen Seite den menschlichen Kehlkopf verkörpert durch die Bewegungen und Gestaltungen des ganzen Menschen und der Menschengruppen sehen, auf der anderen Seite die Dichtung, das Musikalische hören, sodass sich beides ergänzt, beides sich vereinigt zu einem Gesamtkunstwerke. Und verstanden sollte werden, sehr verehrte Anwesende, dass die die eurythmische Kunst begleitende Rezitation nun auch dadurch, dass sie eben als eine besondere Kunst-Ergänzung auftritt zu der Eurythmie, anders gehalten werden muss als dasjenige, was man heute gewöhnlich unter Rezitation versteht.

Das Rezitieren ist heute eigentlich aus dem eigentlich Künstlerischen schon herausgetreten. Das Rezitieren beschränkt sich heute eigentlich auf Pointisierungen des dichterischen Inhaltes. Gerade das Auffinden einer Kunstform, wie sie der Eurythmie zugrunde liegt, wird ja wiederum dazu führen, die Rezitation selbst zu demjenigen zurückzuführen, was sie einstmals war, was diejenigen, die heute jünger sind, gar nicht mehr wissen. Diejenigen, die heute älter sind, wissen sich noch zu erinnern an die Rezitatoren der Siebziger-, Achtzigerjahre, die vielleicht schon in der Dekadence, aber eben doch noch einen Nachklang dessen boten, was Rezitierkunst früher war. Wenige Menschen wissen heute, dass Goethe in Weimar für die Bühne die «Iphigenie» einstudiert hat mit dem Taktstock wie ein musikalisches Kunstwerk. Dass man durchhörte das Rhythmische, das eigentlich Künstlerische, das war das Bestreben zum Beispiel auch Goethes. Diese Rezitationskunst ist verloren gegangen. Durch die Eurythmie wird sie in einer gewissen Weise sich wiederum notwendig machen. Heute will man gar nicht mehr hören dasjenige, was das eigentlich Dichterische, Künstlerische ist: Das ist die dichterische Form, das ist nicht dasjenige, was man in Pointisierung des Inhaltes zum Ausdrucke bringen kann. Im Grunde genommen ist ja heute Rezitationskunst nichts weiter als ein besonders raffiniert ausgebildetes Prosalesen. Und erst auf dem Umwege durch die Eurythmie wird wiederum Rezitations-, Deklamationskunst gefunden werden müssen. Das versteht man heute nicht.

So möchte ich Sie bitten, sehr verehrte Anwesende, in dem dargelegten Sinne unsere Vorstellung aufzunehmen, vor allen Dingen zu bedenken, dass wir selbst eben - wie ich eingangs gesagt habe - sehr bescheiden denken über dasjenige, was wir schon leisten können. Allein, wenn ihm Verständnis entgegengebracht wird, so wird es sich weiter entwickeln können. Und wir sind einmal der Überzeugung: Heute stehen wir noch mit dieser Eurythmie am Anfange ihrer Entwicklung. Aber wir selbst noch - oder vielleicht nicht wir selbst, sondern andere - werden aus ihr etwas herausholen können, was sich als eine besondere neue Kunstform neben andere Kunstformen hinstellen kann.

Besonders wichtig wird das erscheinen - weil heraufgehoben ist das künstlerische Gestalten bis zum Menschen -, worauf Goethe direkt in seinem schönen Buch über Winckelmann hinweist, in dem er sagt: Wenn der Mensch an den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, sieht er sich wieder als eine ganze Natur an und bringt hervor, nimmt Harmonie, Ebenmaß, Sinn, Bedeutung und Inhalt zusammen, um sich endlich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes zu erheben.

In der Eurythmie soll etwas dargeboten werden wie ein Kunstwerk, das unmittelbar aus dem, was im Menschen an Bewegung und innere Kräftemöglichkeiten selbst liegt, zur äußeren Offenbarung kommt. Dass davon ein Anfang gemacht worden ist in unserer Eurythmie, das bitte ich Sie zu berücksichtigen. Und in diesem Sinne bitte ich Sie, unsere Darstellung aufzunehmen und ihr Ihre Nachsicht und Aufmerksamkeit zukommen zu lassen.

[Nach der Pause:]

Im zweiten Teil werden wir Ihnen aus Goethes «Faust II» die Szene um «Mitternacht» vorführen, die sogenannten «vier grauen Weiber»: Sorge, Schuld, Mangel, Not.

Es ist ja so, dass gerade diese Szene wird angesehen werden können als eine Art Probe auf unsere eurythmische Kunst. Es wird sich zeigen, dass man aus «Faust», in den Goethe, wie er selbst sagte, so vieles hineingeheimnisst hat, gerade durch die Eurythmie manches wird herausholen können, was durch die gewöhnliche Bühnendarstellung eigentlich bis jetzt gar nicht hat herausgeholt werden können, - Wenn man öfters die Darstellungen des ersten Teiles des «Faust» gesehen hat - ich will sagen: die Darstellung zum Beispiel auf der einen Seite, wie die [Devrient’sche-Lassen’sche], dann hat man das Gefühl, das stilisiert dasjenige, was Goethe nicht nur inhaltlich, sondern dem Stile nach der höheren Kunstform auch in den «Faust» hineingeheimnisst hat, das komme auf diese Art [Mysterieneinrichtung] etwa heraus; [doch] dann wird die Sache sehr leicht opernhaft. Auf der anderen Seite: Bleibt man bei der schauspielerischen Darstellung etwa - ich erinnere mich an die Wilbrandt’sche Darstellung, oder an andere - so kann sehr leicht das eintreten, dass gerade solche Szenen, die so tief in menschliche Seele hineinleuchten wie diese Sorge-Szene, leer und armselig bleiben.

Gerade die Art, wie durch Eurythmie dasjenige, was Goethe so stilvoll im zweiten Teil des «Faust», in dieser Dichtung als das Allerreifste eigentlich versucht hat zum Ausdruck zu bringen — gerade diese Art der eurythmischen Darstellung wird sich am besten dazu eignen, vielleicht eben durch die Eurythmie das herausholen zu lassen, was Goethe gemeint hat. Und deshalb wird man an der Darstellung dieser Szene gerade solch einen Versuch machen können, zu zeigen, wie mit Zuhilfenahme der Eurythmie neben dem Schauspielerischen aus diesen Künsten ein zusammenhängendes Ganzes wird entstehen können.