Human Questions and World Answers

GA 213

14 July 1922, Dornach

Automated Translation

Ninth Lecture

The purpose of last week's lectures was to provide a certain historical perspective, showing how especially deeper-disposed personalities had to struggle with the currents of the 19th century, and in particular, how the contemporary scientific way of thinking prevented deeper natures from finding their way into the spiritual world. When we make observations directed at the personal, as we have done in relation to Franz Brentano, we can see much more intimately, in the inner soul struggles of human beings, in what has taken place in the spirit, what the great struggles and currents of the time are, than when we characterize only in the abstract. In the last issue of our journal 'Das Goetheanum', I pointed out how Franz Brentano, who, starting from Catholicism and immersing himself in the scientific mentality, got stuck, so to speak, in the physical-earthly, no longer found his way back into the spiritual, as he faced another personality who actually - albeit with some modification - suffered the same fate. That is Nietzsche's personality.

Just as one can show in the case of Brentano how the natural-scientific world view took hold of him and never let go of his devout Catholicism, and how one can show how this characterizes the entire course of his philosophical development, one can show something similar in the case of Nietzsche. It can be shown that Nietzsche, starting not from Catholicism but from a different spirit, was also held back by natural science within the physical-sensual, just as he could not, like Brentano, rise into the spiritual, but then his fate took a similar but still different path.

Brentano immersed himself in the spirit of natural science as early as the 1860s, and we have seen how the dogma of infallibility, as a wave of fate bearing down on him from outside, so to speak, then completely alienated him from his church. Nietzsche, who is a few years younger, went through a similar process of development in the 1870s. He did not start out from Catholicism. He actually started from an antique-like artistic world view, from what the modern human being develops as a world view when he absorbs more of the Greek way of looking at the world in his youth. And it can be said that Nietzsche was as passionate about the Greek way of looking at the world and about an artistic world view in general as Brentano was about Catholicism. He believed that in Richard Wagner and his art he found a renewal of Greekness. And just as Brentano had participated in all Catholic practice and had completely absorbed himself in everything that Catholic worship can evoke within a person, so Nietzsche immersed himself in Wagner's art, in which he believed he saw a resurrection of what the Greek way of looking at the world was. This is how he wrote his first writings, and this is how he experienced the irruption of the scientific way of thinking into his soul in the 1870s.

Before that, he was filled with the view that great human ideals are given to man in an independent spiritual sphere, that man can place these great ideals, the moral, the religious ideals, before his soul, that he finds in them the possibility of rising above the physical-human. And Nietzsche finds words of extraordinary enthusiasm and high flight to describe man's assimilation of ideals. Then the scientific view comes over him. And he feels he must increasingly imbue himself with the thought that the physical in man, in its broadest sense, also produces the ideals as results. It is unsettling for him to have to abandon the old belief that ideals are something independent, something rooted in an independent spiritual world, that ideals actually emerge as the results of what bodily-physical processes are. Nietzsche, so to speak, submerges with all that lives in his ideas as ideals into the physiology of human nature. What had previously seemed divine and spiritual to him now seems merely human, even all too human. He used to see how man has devoted himself to idealistic worlds, how he has elevated himself above base nature by devoting himself to them. Now he believed he recognized that man's lower nature develops only one kind of drive, becoming more and more powerful, and that the holding up of ideals is nothing more than a means of intensifying the inner power in man. In short, Nietzsche strove to explain all ideals as a kind of illusion of physiological processes in the broadest sense. He did not, however, conceive of these physiological processes in man in as philistine a way as today's natural science; but he wanted to regard ideals as a result of physiological, physical processes in the broadest sense. And so, for him, ideals became something that clouds the minds of people who do not see through them, while those who see through them are enlightened about the fact that ideals, like ordinary urges, arise from the physiological foundations of the human being and are only intended to bring the physical nature of the human being more and more powerfully to bear in the broadest sense.

Of course, this is a somewhat radical and retouched description, but it essentially reflects what had such a devastating effect on Nietzsche, especially when he believed that he had come to the conclusion that conscience, too, can only be explained from a physiological basis.

It is only that the natures of the two personalities are different: Brentano is a subtle mind, attuned to imagination, to cognition; he uses the natural-scientific method to create, as it were, an instrument with which he then wants to dissect human mental life in a subtle way, just as natural science dissects physical life. But this instrument becomes blunt at the moment when he wants to approach the real spiritual world. Nietzsche, when he comes to the conclusion that, according to the opinion of natural science, the physiological is the basis of everything, or at least according to its consequences, forms an instrument for himself that is not a fine analytical knife, like Brentano's, but a hammer, robust enough to get everything that is spiritual out of the physical, even physiologically. With this instrument, which is now robust enough to transform the moral and the ideal into the physiological, he grinds the intellectual to dust. He titled one of his writings: “Twilight of the Idols, or How to Philosophize with a Hammer.”

Brentano shrinks from the spiritual, as it were. Nietzsche crushes the spiritual. Basically, anyone who looks at the inner cultural history of the most recent times must find a profound similarity between these two personalities, despite all their differences. And yet, in the very latest writing of which I spoke to you recently, Brentano has a short chapter on Nietzsche in which he shows that he has nothing but mere rejection for Nietzsche. He calls him a belletristic, dazzling mayfly. He compares him to Jesus and finds that Nietzsche is a caricature of Jesus. One cannot help but say: It is strange that a man of such extraordinary refinement as Franz Brentano did not develop a way of penetrating, even to some extent, into the experiences of another mind that was so similar to his in character and destiny, as I have described.

But this is a general phenomenon of our time and only highlights, with excellent examples, what people are like today. They do not live in each other, they live apart. I have often emphasized that they pass each other by without understanding, and that is also a social phenomenon of our time. People pass each other by, even the strongest seekers of truth. Other people do it too, but with such outstanding personalities, what appears as significant symptoms is actually a general phenomenon of our time. Why do people pass each other by without understanding? We so urgently need the possibility of mutual understanding! Today we so urgently need the possibility that someone penetrates both Nietzsche and Brentano, or for that matter Haeckel, David Friedrich Strauß and so on, in order to show how these different personalities look at the world from the most diverse points of view. But only the spiritual-scientific view, the one that really ascends to the spirit, can achieve such a view that delves into the individual personal points of view. And that is precisely the reason why people do not understand each other: that they do not ascend to the spirit. We must seek the reason why a personality like Brentano, in the mere natural science, remained stuck, in the mere natural science, why he could not create a bridge to another personality, who basically had a very similar fate to his own. Only a spiritual deepening will be able to penetrate the most diverse points of view. But for this, a penetrating study of the human being, a penetrating knowledge of the human being, is necessary. For what do such personalities, who are seized by the scientific methodology of the 19th century, like Brentano and Nietzsche, ultimately face?

One day they are confronted with the fact that, as honest seekers of knowledge and truth, they have, on the one hand, the physical world and the excellent scientific methods for penetrating into it; on the other hand, a spiritual world. Of course, people like Nietzsche and Brentano did not go so far as the superficiality that many today display, who do not even see this spiritual world as the great opposite of the physical world. They see the physical world, they see the spiritual world, but there is no bridge between the two. They see what man wants by virtue of his basic nature; they see the will that is based on instincts and impulses, and they attempt to explain these impulses and instincts from the physiological nature of man, how they accumulate, as it were, into volition. But then they notice that a spiritual world erects ideals above them, which are to be striven for; they notice the 'should' in relation to the 'wanting', and they find no bridge between the 'wanting' and the 'should'. A person like Brentano becomes a psychologist, a scientist of the soul. Physiology is, after all, to a certain extent complete. But he wants to examine the phenomena of the soul. He wants to imitate natural science by investigating the phenomena of the soul. At first he is not at all certain whether he has soul phenomena, because in a sense science denies this. Brentano is actually only certain that there are soul phenomena because he was a devout Catholic for so long, not out of any scientific knowledge.

This dichotomy is terrible in the soul of these people: the spiritual world, the physical world, and no bridge between the two. How do you get from one to the other? The moral ideals are there. But it is not possible to understand how what the moral ideals want can take hold of the human muscles, how it can lead people to action. For science merely says how muscles and bones move according to physical laws, but not how the ought is reflected in the movement of muscles and bones.

The point is that, however perfect the scientific method may be, this scientific century was basically helpless when it came to the human being. You simply could not examine the human being. It did not occur to anyone that the human being is a threefold being, in the way I have described in the last sections of my book 'Von Seelenrätseln' (The Riddle of the Soul). It was not possible to arrive at the conclusion that the human being can be divided into a nervous-mental human being, which naturally fills the whole human being but is mainly localized in the head; into a rhythmic human being, which in turn permeates the whole human being but is mainly concentrated and localized in the respiratory and circulatory organs; and finally into the metabolic human being of the limbs, which is the remaining human being. This is such a profound fact that everything that is to lead to an understanding of the human being must be linked to it. Of course, one must not say that the three parts of the human being are the head, chest and limbs. I have already said that the human being is a nerve-sense being everywhere, only this is primarily expressed in the head. But look at this head. It is so formed that we cannot but be filled with ever deeper admiration when we consider the structure, especially the nervous structure, of the human head. Within the world of physical phenomena, there is nowhere to be found any real reason why the human head, especially in its inner parts, should be formed precisely as it is.

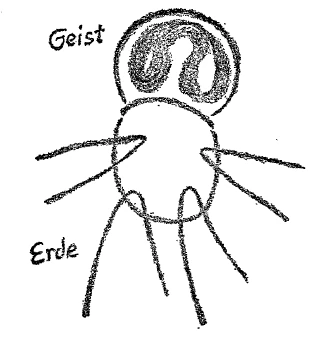

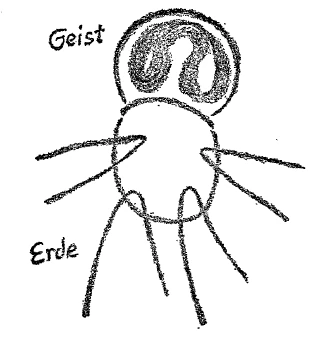

This is where the realization I have often spoken of here occurs. The human head is modeled on the cosmos in its outer form, if you disregard the base of the head. It is actually spherical in shape (see drawing). Its form is taken from the cosmos. All the cosmic forces in the mother's body also work together to first create the human head during embryonic development. If we look at this spiritually, we see that the human being's soul and spirit live in a spiritual world before the person descends into physical earthly existence, first connecting with the cosmic forces and only then taking hold of the forces of heredity. The actual spiritual-soul-man first forms out of the ether of the world and only then goes to the physically ponderable matter that is offered to him in his mother's body. So actually this head is formed out of the cosmos, and what has descended from man out of spiritual-soul worlds to earth is imagined from this cosmic formation. Therefore, in the physical world, no one understands the structure of the human head who does not explain it in spiritual terms, saying: the human head is an image, an immediate imprint of the spiritual. These wonderful convolutions of the brain, everything that can be discovered physiologically in the human head, is as if it were crystallized spirit, spirit present in material form. The human head is, as a physical body, an immediate image of the spirit.

If someone were to sculpt the spirit as such, they would actually have to study a human head permeated by spirit. Of course, if they are a model artist, they will not capture anything special; but if they are not a model artist, but create from the spiritual, then they will achieve a wonderful image of the innermost nature of the cosmic spiritual forces when they create the human head. What is present in the human head is intuition, inspiration, imagination of cosmic spirituality. It is as if the Godhead itself had wanted to create an image of the spiritual and had placed the human head on it. It is therefore basically comical when people seek images of the spirit, while they have the best, the most magnificent, the most powerful image of the spirit, but precisely the image of the spirit, not the spirit itself, in the human head.

The opposite is the case with the human being with limbs. If you contrast the human being with limbs, they are only attached to the earth. They have only one sense as an attachment to the earth. The arms are somewhat lifted out of the earthly. In animals, those limbs that are arms in humans are also still attuned to the heaviness of the earth. But essentially, the nature of the human limbs is thoroughly organized around the forces of the earth. Just as the human head is a reflection of cosmic spirituality, so what we encounter in the human limbs shows us how the spirit is bound to the forces of the earth. Just study the shape of a human leg with a human foot! If you want to understand it in a plastic way, you have to understand the forces of the earth. Just as you have to understand the highest spirituality if you want to grasp the human head, so, in order to understand the form of the limbs, you have to study what binds the human being to the earth, what presses him to the earth, what causes the human being to be able to walk along the earth and to sustain himself in space within the forces of gravity. All this must be studied, the whole way the earth affects a being that relates to it in this way, as man does. Just as one must study the spirit in order to understand the human head, so one must study the physical of the earth with its forces in order to understand the human being in terms of his limbs and metabolism.

But this has a very significant consequence. Only when one looks into the human being in this way, when one is able to see the human head as it were, in the crystallized, all-encompassing spiritual world, and when one sees in the lines of gravity and again in the lines of momentum, in which the earth turns, the origins of the formations of the human limbs, when one sees through dynamically, in the effect of the forces, the way in which the human being is formed and built, only then can one form an opinion about it.

of the formation of the human limbs, when one sees dynamically, in the effect of the forces, the way in which the human being is formed and built, only then can one form an opinion about how the spiritual and soul life that occurs in the human being itself now works in the human being. And I would like to tell you about this today using two examples.Two things can play a major role in the human soul that are, to a certain extent, opposed to each other. One is what I would call doubt, and the other is what I would call conviction. One could perhaps also find other, even more succinct words. But you will all feel that we have a kind of polar opposite of the soul when we speak of doubt on the one hand and conviction on the other. Imagine what happens when a person is seized by doubt on the one hand and conviction on the other, and this happens on a more intense level. Try to visualize yourself being seized by doubt about something, even if it is only a matter that is occupying you intensely. It does not have to be a great cosmic truth or a great cosmic riddle, just a matter that interests you greatly. You must go to bed with this doubt. Imagine tossing and turning, feeling restless, and unable to find peace of mind. And then try to visualize how something flows into your soul as a soothing conviction, bringing an inner calm, how, as it were, a warmth of soul can fill you completely. In short, if you really look at the matter impartially from within, you will be able to visualize before your soul the opposite natures of doubt on the one hand and conviction on the other.

What is the difference in relation to the essence of the human being? The human head is modeled out of the cosmic ether from what we were in the spiritual world; the human head is a pure replica of the most human, namely the spiritual human being. Doubting ideas come to the head, but they find no place in the head. The head does not absorb them. They have to pass through the head down to the nature of the limbs. In the nature of the limbs, they combine with everything that becomes grainy in the human material being, that becomes so that it permeates this human material being grainily, that thus takes on an atomistic nature. Doubting ideas pass through him as if our head were permeable to them. The blood first absorbs these doubting ideas, then they are carried down into the whole organism, preferably absorbed by the metabolism, and only then handed over to the nervous system, and they live in all that is atomistic in human nature, that is, granular, salty. They connect with it very intimately. The body absorbs the doubting ideas, and they pass through the head. Only when one understands this special kind of human head, and that the matter of the head is not suitable for doubting ideas, because the head is an image of the truth itself, from which we come when we descend from the spiritual into the physical , we understand: just as light passes through a transparent glass, so do doubting ideas pass through our head and take hold of the other part of the nervous system and disturb our metabolism. The head only takes in doubting ideas to the extent that it itself is a matter of metabolism. But it passes them through its special nervous organization and only takes in convincing ideas.

The convincing ideas find related structures everywhere when they enter the human head. They find accommodation everywhere in the nervous system. They settle in the human being's head first and go out into the rest of the body not through the blood but through the nervous system, which is in a kind of destructive process, so that they pass directly into the whole of the rest of the human being in their spirituality. But they find accommodation in the head, they fill the head. And in the head, from the spirituality of the head form, also from the inner formation, they receive their suitable form for the whole person and therefore work as if they were intimately related to the person, as if the person himself would live in them inwardly, as if they were the person himself. One would like to say: In the convincing representations, the head of the person forms something that is particularly appropriate for the person.

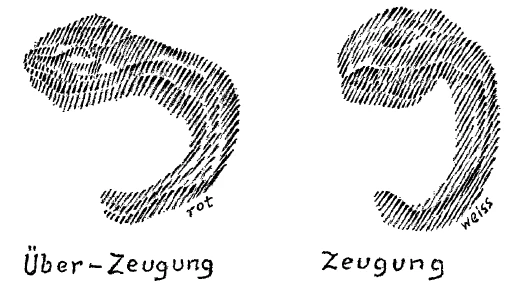

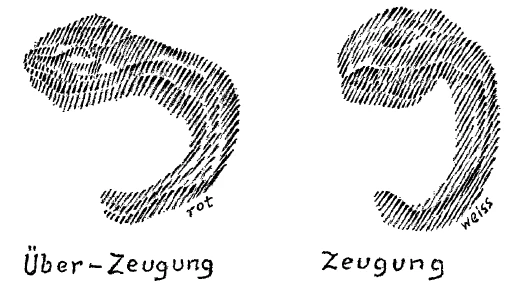

Study the human embryo and you will see that the head forms first, then the rest of the organism; for it is from the head that the forces that form the rest emanate. When you take convincing ideas into your head, it is like this spiritually: they are first taken up spiritually in the head, and the head then sends them to the rest of the human being. Just as the other person is physically reproduced in the embryo according to the human head, so here the spiritual of the convictions and ideas of the other person is radiated, and a person arises from it in a spiritual way from the convincing ideas (left drawing, red). An inner image of a person radiates in that person. And whatever radiates in the form of convincing ideas in a person connects with everything that permeates the person like warmth. Just as the doubting images seize everything granular, everything atomistic, so the convincing images seize the warmth flowing through the body, the first link of the etheric that permeates the whole human being, and do not enter further into the physical.

Try to imagine the presence of doubting and convincing ideas in human nature, and you can grasp the truth of the matter in immediate life every time you feel and experience the beneficial effect of a convincing idea and the torturous effect of doubting ideas.

I have often said that the spirit of language is a spirit that works rationally. And if you ascribe the natural embryo to procreation (drawing on the right, white), you are not at all surprised that this formation is attributed to conviction (on the left, red). We must not regard these things as mere coincidences. They are the deeds of the ruling genius of language, which knows more than the individual human being. I know that today's linguistic science regards this as a gimmick. But once one really looks into the workings and weaving of the ruling language genius, one will regard much of today's philology and linguistics as gimmicks.

But now consider what it all means. You get a picture of how two soul experiences, doubt and conviction, continue to work in the physical person. They provide an absolutely comprehensible bridge from the soul and spirit to the physical. You see a physical person, and through his physical corpuscles in his body you can see the shimmering and undulating of his soul and spiritual experiences: this person is a skeptic, this one a doubter. You can see how the doubting spirit vibrates on in the soul and in the body through the inner structure of the material. You look at the other person, in whom the warmth flows through the limbs in a calm manner, and you see in this calm flow of warmth the physical expression of devotion to one's convictions. You see the spiritual directly expressed in the physical. Only then do you begin to understand the physical. Today's chemist and physicist says when he analyzes the human being: Inside there is lime, phosphorus, oxygen and nitrogen, carbon. Yes, you will never find anything spiritual in oxygen and nitrogen and carbon and hydrogen. Of course Du Bois-Reymond is quite right when he says: A number of oxygen and nitrogen and carbon atoms can be completely indifferent to how they lie and move. Yes, if you look at the substance in the body only as carbon, oxygen and so on, then it is like that. But if you know how a substance works that is receptive to the spirit in the most diverse ways, that is in the main an immediate image of spiritual essence, that is otherwise incorporated into the earth, so that the earthly holds there, which is driven through the head as doubting ideas, then the possibility of thinking ceases. It is not the same in our brain for a number of carbon, nitrogen atoms, and so on, as they lay and moved, as they lie and move. There we see how it matters to the substance whether the heat current flows into it or whether salt formation is at work in it, so that the body develops a tendency to develop a granular structure. These are two contradictions that express themselves in the material and that originate from the spiritual. It is actually the case that we did not end up with materialism in the 19th century because people did not know the spirit. The spirit in its most filtered form was best known in the materialistic age, because all previous ages did not actually have the spirit in its purest form; they always mixed material into the images of the spirit that they formed; they were images in which material was always mixed. Only the age of natural science has brought pure spiritual conceptions. But what the age of natural science had to neglect is just the knowledge of matter in reality, of spirit in matter. What has brought us materialism is the insufficient knowledge of the material nature of the world, the lack of insight into the spiritual weaving and working in the material. Science has become materialistic through ignorance of the material effects. Because people did not know how the spirit works creatively, they imagined this spirit as more and more abstract and abstract. As a result, the moral ideal finally became something that one could not even ask about, because it did not even have the materiality to fly around in space. It was no longer there at all. If you tried to grasp it, it was rather like trying to breathe in an element that is not there. The people of the 19th century seem like someone trying to breathe under the recipient of an air pump! When they gasp for moral ideals, for example, they are not there; they would like to have them, but they are not there because no one wanted to develop a concept of the workings of the spiritual soul in the physical body. Hence all the curious theories arose about the interaction of the physical and the bodily with the soul and spiritual, which were all fabrications, while real knowledge can only be gained by looking closely at the facts.

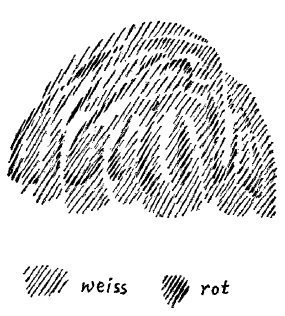

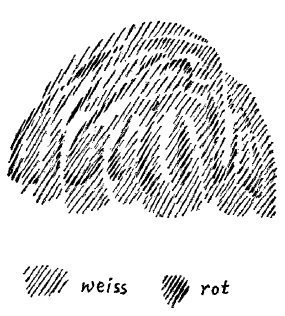

When we have become familiar with how doubt and conviction permeate and interweave human nature, then we are able to become acquainted with that which we have come to know in man and in turn to know it in the world. We have in the world the sphere of material creation. We see, for example, how matter must form itself in grains out in the world, how it crystallizes. Once we have become familiar with how doubt takes hold of the granularity in us in the organism, we then learn to see doubt outside of us. We look at the mountain (white) that forms with its granular rock; but at the same time we find that the same thing is happening in the mountain that we are getting to know as doubt within us (red), and we get to know the creative power of doubt. The doubt within us makes us grainy because we are human and not nature. Doubt outside in nature has the right effect. When that which works outside in nature moves in us, it causes the wrong. By stepping on the rocks, you are stepping on the physical manifestation of what the deity sends out as doubt so that the world can become grainy. And again, when you study your convictions with a warm sense of being imbued, then you are in that which is being created. So when you think that basically the warmth is to be sought in the womb of the creative forces of the world, then you find that what is cosmic conviction works out of warm matter.

Get to know these things in truth within yourself, then you will also learn to judge the agents out there in the cosmos in the right way. If you see what is crumbling and crumbling away out there, so that we have, so to speak, the first preparation for the atomization of our earthly existence in the universe, as emanations of world doubt, then you will learn to understand much in cosmic existence. And conversely, if you are able to look into the cosmic with conviction, then you will get to know much of the Creative. But these are things by which I only wanted to hint to you how one must first know man in order to have any prospect at all of knowing the cosmic existence.

Well, you see, for Brentano in the 1860s and for Nietzsche in the 1870s, the methods of natural science were there; they found carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, some sulfur, and so on in the brain. There was really nothing spiritual to be recognized in it. And if one applied the method that had led to this to the spirit, then of course one could come to nothing but either the spiritual impotence that Brentano came to, or the wearing down of the spiritual that Nietzsche, who was more of a will nature, came to. But both were subject to the same fate, namely that they could not reach the spiritual from the physical, because they could not find the spiritual in the physical, and therefore did not perceive the spiritual as something powerful enough to bring forth the physical.

Thus, such minds were faced with a physical nature that actually had no meaning because it contained nothing spiritual, and with a spiritual nature that had no power, no might. That is the fate of the most significant minds that in the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century faced matter without meaning, faced the spirit without power.

Historians have spoken of ideas in history. This is mind without power. You really cannot put cultural instruments into the hands of ideas, through which culture arises, or through which historical events arise at all; ideas as abstractions are powerless, this is mind without power. In contrast to this is nature, which one studies only in its unspiritual matter: matter without meaning.

You will never find the bridge if you invent the absurdity on one side: matter without sense, and on the other side the un-spirit: spirit without power. Only when one finds the strength in the spirit, the strength in the conviction to drive the warmth through the body because the human being is organized in such and such a way, only when one finds the strength in the doubt to push through the head because there is no affinity with the head and to wear down the rest of the human being internally so that it disintegrates into a granular structure , that is, only when one finds in the spirit that which has the power both to dissolve the granular structure through warmth and to form it in the salt formation process, then one finds a matter in which meaning is, because then the powerful spirit works in such a way that what appears in matter is meaningful. And so we have to look for matter with meaning and spirit with power.

This is what such minds as Brentano and Nietzsche, in their tragic fate, also point to in their personalities.

Neunter Vortrag

Die Vorträge der letzten Woche sollten in einer gewissen Beziehung geschichtlich darauf hinweisen, wie gerade tiefer veranlagte Persönlichkeiten mit den Zeitströmungen des 19. Jahrhunderts zu kämpfen hatten, und es sollte namentlich gezeigt werden, wie die zeitgenössische naturwissenschaftliche Denkungsart gerade tiefere Naturen davon abgehalten hat, den Weg in die geistige Welt hinein zu finden. Man kann, wenn man auf das Persönliche hin gerichtete Betrachtungen anstellt, wie wir sie in bezug auf Franz Brentano angestellt haben, an den inneren Seelenkämpfen der Menschen, an dem, was sich in den Geistern da abgespielt hat, ja eigentlich viel intimer sehen, wie die großen Zeitkämpfe und Zeitströmungen sind, als wenn man nur im Abstrakten charakterisiert. Ich habe nun in der letzten Nummer unserer Zeitschrift «Das Goetheanum» darauf hingewiesen, wie Franz Brentano, der, vom Katholizismus ausgehend, in die naturwissenschaftliche Gesinnung untertauchend, sozusagen hängengeblieben ist am Physisch-Irdischen, nicht mehr den Rückweg gefunden hat in das Geistige, wie er einer anderen Persönlichkeit gegenüber gestanden hat, die eigentlich - wenn auch mit einiger Veränderung — demselben Schicksal unterlegen ist. Das ist die Persönlichkeit Nietzsches.

Geradeso wie man bei Brentano nachweisen kann, wie ihn aus seinem gläubigen Katholizismus, aus seinem wirklichen katholischen Frommsein heraus die naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung gepackt und nicht mehr losgelassen hat, und wie man zeigen kann, wie das ganze Schicksal seines Philosophenweges dadurch zu charakterisieren ist, so kann man auch ein Ähnliches bei Nietzsche zeigen. Man kann zeigen, daß Nietzsche nun zwar nicht vom Katholizismus, sondern von einer anderen Geistesart ausgehend, auch durch die Naturwissenschaft zurückgehalten wurde innerhalb des Physisch-Sinnlichen, wie er sich ebensowenig wie Brentano in das Geistige erheben konnte, wie aber dann sein Schicksal einen zwar ähnlichen, aber doch wiederum verschiedenen Weg genommen hat.

Brentano ist ja schon in den sechziger Jahren in die naturwissenschaftliche Gesinnung untergetaucht, und wir haben gesehen, wie ihn das Unfehlbarkeitsdogma, gewissermaßen als Schicksalswoge von außen an ihn heranschlagend, dann vollends seiner Kirche entfremdet hat. Nietzsche, der um einige Jahre jünger ist, hat einen ähnlichen Entwickelungsgang in den siebziger Jahren durchgemacht. Er ist nicht vom Katholizismus ausgegangen. Er ging eigentlich von einer antikisierenden, künstlerischen Weltanschauung aus, von dem, was der moderne Mensch als Weltanschauung entwickelt, wenn er in seiner Jugend mehr das Griechentum, die griechische Art, die Welt anzuschauen, in sich aufnimmt. Und man kann schon sagen: Nietzsche stand mit demselben Feuer, mit dem Brentano im Katholizismus gestanden hat, in der griechischen Art, die Welt anzuschauen, und in einer künstlerischen Weltanschauung überhaupt darinnen. Er glaubte, in Richard Wagner und seiner Kunst eine Erneuerung des Griechentums zu finden. Und geradeso wie Brentano alle katholische Praxis mitgemacht hat und sich ganz eingelebt hat in alles, was der katholische Kultus innerhalb eines Menschen hervorrufen kann, so lebte sich Nietzsche in die Wagnersche Kunst ein, in der er eine Wiederauferstehung dessen zu sehen glaubte, was griechische Art, die Welt anzusehen, war. So schrieb er seine ersten Schriften, und so erlebte er dann in den siebziger Jahren den Einbruch der naturwissenschaftlichen Denkungsweise in sein Seelenleben.

Vorher war er erfüllt von der Anschauung, daß dem Menschen in selbständiger Geistessphäre große Menschheitsideale gegeben sind, daß der Mensch sich diese großen Ideale, die sittlichen, die religiösen Ideale vor die Seele stellen kann, daß er in ihnen die Möglichkeit findet, sich über das Physisch-Menschliche zu erheben. Und Nietzsche findet mit außerordentlicher Begeisterung Worte hohen Schwungs, um das Einleben des Menschen in die Realität der Ideale zu schildern. Da kommt die naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung über ihn. Und er glaubt, sich immer mehr und mehr mit dem Gedanken durchdringen zu müssen, daß eigentlich das Leibliche im Menschen in seinem weitesten Umfange auch die Ideale als Ergebnisse aus sich heraussetzt. Es wirkt erschütternd auf ihn, den alten Glauben, daß die Ideale etwas Selbständiges sind, etwas, das in einer selbständigen Geisteswelt wurzelt, verlassen zu müssen, daß die Ideale eigentlich auftauchen als die Ergebnisse desjenigen, was leiblich-physische Prozesse sind. Nietzsche taucht gewissermaßen mit alledem, was in seinen Vorstellungen als Ideale lebt, unter in das Physiologische der Menschennatur. Was ihm früher als göttlich-geistig erschien, es erscheint ihm jetzt bloß als menschlich, ja als allzu menschlich. Er sah früher, wie sich der Mensch idealistischen Welten hingegeben hat, wie er sich durch die Hingabe an diese über die niedrige Natur erhoben hat. Jetzt glaubte er zu erkennen, daß die niedere Natur des Menschen nur eine Art von Trieb entwickelt, immer kraftvoller und kraftvoller zu werden, und daß auch das Vorhalten von Idealen nichts anderes sei als ein Mittel, die innere Intensität der Macht im Menschen zu verstärken. Kurz, Nietzsche strebte dahin, alle Ideale gewissermaßen als Scheingebilde der physiologischen Vorgänge im weitesten Sinne zu erklären. Er hat sich allerdings diese physiologischen Vorgänge im Menschen nicht so philiströs gedacht wie die heutige Naturwissenschaft; aber er wollte die Ideale als ein Ergebnis der physiologischen, der physischen Vorgänge im weitesten Sinne betrachten. Und so wurden ihm die Ideale zu etwas, wodurch sich Menschen, die die Sache nicht durchschauen, benebeln, während diejenigen, die die Sache durchschauen, sich aufklären darüber, daß eigentlich die Ideale ebenso wie die gewöhnlichen Triebe aus den physiologischen Untergründen des Menschen hervorgehen und nur dazu bestimmt sind, die leibliche Natur des Menschen im weitesten Sinne immer mehr zu mächtiger Geltung zu bringen.

Natürlich ist das etwas radikal und retuschiert geschildert, aber es gibt doch im wesentlichen das wieder, was gerade auf Nietzsche so erschütternd gewirkt hat, namentlich auch als er glaubte, darauf gekommen zu sein, daß man auch das Gewissen nur aus physiologischen Untergründen heraus zu erklären habe.

Es sind nur die Naturen der beiden Persönlichkeiten verschieden: Brentano ist ein feiner Geist, auf das Vorstellen, auf das Erkennen hin gestimmt; er bildet sich gewissermaßen mit der naturwissenschaftlichen Methode ein Instrument, mit dem er dann in einer feinsinnigen Weise das menschliche Seelenleben zergliedern will, wie die Naturwissenschaft das physische Leben zergliedert. Dieses Instrument wird aber stumpf in dem Momente, wo er an die wirkliche geistige Welt herangehen will. Nietzsche, als er darauf kommt, daß das Physiologische nach der Meinung der Naturwissenschaft der Grund von allem ist oder wenigstens nach deren Konsequenzen, bildet sich ein Instrument, das nicht ein feines Analysiermesser ist, wie das Brentanos, sondern das ein Hammer ist, robust genug, um alles, was geistig ist, auch aus dem Physischen physiologisch herauszuholen. Mit diesem Instrumente, das nun robust genug ist, um das Moralische, Idealische in ein Physiologisches zu verwandeln, zermürbt er das Geistige. Er hat eine seiner Schriften betitelt: «Götzendämmerung oder wie man mit dem Hammer philosophiert.»

Brentano zuckt gewissermaßen vor dem Geistigen zurück. Nietzsche zerschlägt das Geistige. Im Grunde genommen muß derjenige, der die innere Kulturgeschichte der neuesten Zeit betrachtet, bei aller Verschiedenheit eine tiefgehende Ähnlichkeit dieser beiden Persönlichkeiten finden. Und dennoch, gerade in der neuesten Schrift, von der ich Ihnen neulich gesprochen habe, hat Brentano ein kurzes Kapitel über Nietzsche, in dem er zeigt, daß er für Nietzsche gar nichts anderes hat als bloße Ablehnung. Er nennt ihn eine belletristisch schillernde Eintagsfliege. Er vergleicht ihn mit Jesus und findet, daß Nietzsche eine Karikatur von Jesus ist. Man kann nicht anders sagen als: Es ist eigentümlich, daß ein so außerordentlich feiner Mensch wie Franz Brentano nicht ein Organ entwickelt, um auch nur einigermaßen in das einzudringen, was ein anderer Geist erlebt, der ihm im Grunde und in seinem Schicksal so ähnlich ist, wie ich es Ihnen dargestellt habe.

Das ist aber überhaupt eine Zeiterscheinung für unsere Gegenwart und drückt nur an ausgezeichneten Beispielen aus, wie die Menschen heute sind. Sie leben sich nicht ineinander, sie leben sich auseinander. Ich habe es oftmals hervorgehoben, sie gehen aneinander ohne Verständnis vorbei, und das ist durchaus auch eine soziale Erscheinung unserer Zeit. Die Menschen gehen aneinander vorbei, selbst die stärksten Wahrheitssucher. Die anderen Menschen machen es allerdings auch so; nur kommt bei solchen ausgezeichneten Persönlichkeiten in bedeutungsvollen Symptomen zum Vorschein, was allgemeine Zeiterscheinung ist. Warum gehen denn die Menschen so verständnislos aneinander vorbei? Wir bräuchten so sehr die Möglichkeit des gegenseitigen Verständnisses! Wir bräuchten heute so sehr die Möglichkeit, daß jemand eindringt sowohl in Nietzsche wie in Brentano oder meinetwillen in Haeckel, in David Friedrich Strauß und so weiter, um zu zeigen, wie von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus diese verschiedenen Persönlichkeiten die Welt anschauen. Aber zu einer solchen, in die einzelnen persönlichen Standpunkte aufgehenden Betrachtung kommt doch nur die geisteswissenschaftliche Anschauung, diejenige, die nun wirklich zum Geiste aufsteigt. Und das gerade ist der Grund, warum die Menschen einander nicht verstehen: daß sie nicht zum Geiste aufsteigen. Wir werden in der Erscheinung, daß eine Persönlichkeit wie Brentano an dem bloßen Naturwissenschaftlichen hängen blieb, den Grund suchen müssen, warum er gar keine Brücke schaffen konnte zu einer anderen Persönlichkeit, die im Grunde genommen ein stark ähnliches Schicksal wie er selbst hatte. Erst die geisteswissenschaftliche Vertiefung wird in die verschiedensten Standpunkte eindringen können. Dazu aber ist eben eine eindringende Menschenbetrachtung, eine eindringende Menschenerkenntnis notwendig. Denn, wovor stehen im Grunde genommen solche Persönlichkeiten, die von der naturwissenschaftlichen Methodik des 19. Jahrhunderts ergriffen werden, wie Brentano, wie Nietzsche?

Sie stehen eines Tages vor der Tatsache, daß sie als ehrliche Erkenntnissucher, als ehrliche Wahrheitssucher auf der einen Seite die physische Welt haben, die ausgezeichneten naturwissenschaftlichen Methoden, um in die physische Welt einzudringen; auf der anderen Seite eine geistige Welt. Bis zu jener Oberflächlichkeit, zu der es heute viele bringen, daß sie diese geistige Welt zunächst überhaupt gar nicht als den großen Gegensatz zu der physischen Welt sehen, konnten es Menschen wie Nietzsche und Brentano natürlich nicht bringen. Sie sehen also die physische Welt, sie sehen die geistige Welt, aber zwischen beiden ist keine Brücke zu schlagen. Sie sehen, was der Mensch aus seiner Naturgrundlage heraus will; sie sehen jenes Wollen, dem die Instinkte, die Triebe zugrunde liegen, sie versuchen, aus der physiologischen Natur des Menschen heraus diese Triebe, diese Instinkte zu erklären, wie sie sich gewissermaßen zusammenballen zum Wollen. Dann aber merken sie, daß eine geistige Welt Ideale über ihnen aufrichtet, denen nachzustreben ist; sie bemerken gegenüber dem Wollen das Sollen, und sie finden keine Brücke zwischen dem Wollen und dem Sollen. Ein Mensch wie Brentano wird Psychologe, Seelenwissenschafter. Die Physiologie ist ja bis zu einem gewissen Grade fertig. Er will aber die Seelenerscheinungen untersuchen. Er will es in der Untersuchung der Seelenerscheinungen der Naturwissenschaft nachmachen. Er ist zunächst einmal gar nicht sicher, ob er Seelenerscheinungen hat, weil ihm die Naturwissenschaft das in gewissem Sinne bestreitet. Brentano ist eigentlich nur deshalb sicher, daß es Seelenerscheinungen gibt, weil er so und so lange frommer Katholik war, nicht aus irgendeiner wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnis heraus.

Dieser Zwiespalt steht furchtbar in der Seele dieser Menschen: die geistige Welt, die physische Welt, und keine Brücke zwischen beiden. Wie kommt man von einem zum anderen? Die sittlichen Ideale stehen da. Aber es ist mit der Erkenntnis nicht einzusehen, wie das, was die sittlichen Ideale wollen, die menschlichen Muskeln ergreifen kann, wie das den Menschen zum Handeln führen kann. Denn Naturwissenschaft sagt eben bloß, wie sich nach physikalischen Gesetzen die Muskeln und die Knochen bewegen, aber nicht, wie das Sollen einschlägt in die Bewegung der Muskeln und Knochen.

Da handelt es sich darum, daß im Grunde genommen bei aller Vollkommenheit der naturwissenschaftlichen Methode dieses naturwissenschaftliche Jahrhundert dem Menschen gegenüber doch ganz hilflos war. Man konnte den Menschen einfach nicht untersuchen. Man konnte nicht darauf kommen, daß der Mensch ein dreigliedriges Wesen ist, in der Richtung, wie ich das in den letzten Abschnitten meines Buches «Von Seelenrätseln» dargestellt habe. Man konnte nicht dazu gelangen, den Menschen zu gliedern in einen NervenSinnesmenschen, der natürlich den ganzen Menschen ausfüllt, aber vorzugsweise im Haupte lokalisiert ist, in einen rhythmischen Menschen, der wiederum den ganzen Menschen durchzieht, vorzugsweise aber in den Atmungs- und Zirkulationsorganen konzentriert, lokalisiert ist, dann in den Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselmenschen, der der übrige Mensch ist. Das ist ein so tiefgehender Tatsachenbestand, daß an ihn alles angeknüpft werden muß, was zum Verständnis des Menschen führen soll. Natürlich darf man nicht etwa sagen, die drei Glieder des Menschen seien Kopf, Brust und Gliedmaßen. Ich habe schon gesagt, der Mensch ist überall Nerven-Sinnesmensch, nur prägt sich dieses vorzugsweise im Kopfe aus. Aber sehen Sie sich diesen Kopf an. Er ist so gebildet, daß wir immer tiefer und tiefer in die Bewunderung hineinkommen müssen, wenn wir den Bau, gerade den Nervenbau dieses menschlichen Kopfes ins Auge fassen. Es ist innerhalb der physischen Erscheinungswelt nirgends ein wirklicher Grund aufzufinden, warum das menschliche Haupt, namentlich in seinen inneren Partien, gerade so gebildet ist, wie es eben gebildet ist.

Da tritt jene Erkenntnis ein, von der ich oftmals hier gesprochen habe. Der menschliche Kopf ist schon seiner äußeren Form nach, wenn Sie von der Kopfbasis absehen, dem Kosmos nachgebildet. Er ist ja eigentlich kugelig gebildet (s. Zeichnung). Er ist herausgeholt in seiner Form aus dem Kosmos. Es wirken ja auch alle kosmischen Kräfte im Leibe der Mutter zusammen, um in der Embryonalbildung zuerst das menschliche Haupt zu erzeugen. Wenn wir geistig auf die Sache eingehen, so ist es so, daß dasjenige, was vom Menschen geistig-seelisch in einer geistig-seelischen Welt lebt, bevor der Mensch heruntersteigt ins physisch-irdische Dasein, sich zunächst mit den kosmischen Kräften verbindet und dann erst die Vererbungskräfte ergreift. Der eigentliche geistig-seelische Mensch bildet sich zuerst aus dem Äther der Welt heraus und geht dann erst an die physisch ponderablen Materien, die ihm im Leibe der Mutter dargereicht werden. Eigentlich ist also dieses Haupt aus dem Kosmos heraus gebildet, und das, was vom Menschen heruntergestiegen ist aus geistig-seelischen Welten auf die Erde, ist eingebildet dieser kosmischen Gestaltung. Daher versteht auch im Physischen niemand den Bau des menschlichen Hauptes, der ihn nicht im geistigen Sinne so erklärt, daß er sagt: Das Haupt des Menschen ist ein Abbild, ein unmittelbarer Abdruck des Geistigen. Diese wunderbaren Gehirnwindungen, alles, was da physiologisch im menschlichen Haupte zu entdecken ist, ist so, als wenn es kristallisierter Geist wäre, in materieller Form vorhandener Geist. Das menschliche Haupt ist als physischer Leib unmittelbar Abbild des Geistes.

Wenn jemand den Geist als solchen als Bildhauer darstellen sollte, so müßte er eigentlich einen durchgeistigten Menschenkopf studieren. Er wird natürlich, wenn er Modellkünstler ist, nichts Besonderes treffen; aber wenn er nicht Modellkünstler ist, sondern aus dem Geistigen heraus schafft, dann wird er gerade ein wunderbares Abbild der innersten Natur der kosmischen Geisteskräfte zuwege bringen, wenn er das menschliche Haupt schafft. Es ist Intuition, Inspiration, Imagination der kosmischen Geistigkeit, was im menschlichen Haupte vorliegt. Es ist, wie wenn die Gottheit selber ein Bild des Geistigen hätte schaffen wollen und dem Menschen sein Haupt aufgesetzt hätte. Es ist deshalb im Grunde genommen drollig, wenn die Menschen Bilder vom Geist suchen, während sie das beste, das großartigste, das gewaltigste Bild des Geistes, aber eben das Bild des Geistes, nicht den Geist selbst, im menschlichen Haupte haben.

Ganz entgegengesetzt ist es mit dem Gliedmaßenmenschen. Wenn Sie den Gliedmaßenmenschen dagegenstellen, so ist dieser nur der Erde angegliedert. Der hat nur einen Sinn als Angliederung an die Erde. Die Arme werden etwas herausgehoben aus dem Irdischen. Beim Tiere sind diejenigen Glieder, die beim Menschen die Arme sind, auch noch in die Erdenschwere eingestellt. Aber im wesentlichen ist die Gliedmaßennatur des Menschen durchaus auf die Erdenkräfte hinorganisiert. Geradeso wie das Haupt des Menschen ein Abbild ist der kosmischen Geistigkeit, so zeigt uns das, was uns in den menschlichen Gliedmaßen entgegentritt, wie der Geist da gebunden ist an die Kräfte der Erde. Man studiere nur einmal die Form eines menschlichen Beines mit dem menschlichen Fuß! Will man es plastisch verstehen, so muß man die Kräfte der Erde verstehen. Geradeso wie man die höchste Geistigkeit verstehen muß, wenn man das Menschenhaupt begreifen will, so muß man, um die Form der Gliedmaßen zu begreifen, dasjenige studieren, was den Menschen an die Erde bindet, ihn zur Erde drückt, was verursacht, daß der Mensch der Erde entlanggehen und sich im Weltall erhalten kann innerhalb der Schwerekräfte. Das alles muß man studieren, die ganze Art, wie die Erde auf ein Wesen wirkt, das in dieser Weise sich zu ihr stellt, wie der Mensch es tut. So wie man den Geist studieren muß, um das menschliche Haupt zu verstehen, so muß man das Physische der Erde mit ihren Kräften studieren, um den Gliedmaßen- und Stoffwechselmenschen zu verstehen.

Das aber hat eine sehr bedeutsame Folge. Erst wenn man so hineinsieht in den Menschen, wenn man hinzuschauen vermag auf das Haupt des Menschen, wie es sozusagen die zusammenkrtistallisierte, im ganzen Kosmos ausgebreitete wirkende geistige Welt ist, und wenn man in den Schwerelinien und wiederum in den Schwunglinien, in denen sich die Erde dreht, die Ursprünge der Formungen der menschlichen Gliedmaßen sieht, wenn man so durchschaut dynamisch, in der Kräftewirkung, die Art und Weise, wie der Mensch gestaltet und wie er gebaut ist, dann erst kann man ein Urteil darüber gewinnen, wie das Geistig-Seelische, das im Menschen selber auftritt, nun in den Menschen hineinwirkt. Und das möchte ich Ihnen heute an zwei Beispielen sagen.

Zwei Dinge können im menschlichen Seelenwesen eine große Rolle spielen, die sich gewissermaßen entgegengesetzt sind. Das eine ist das, was ich den Zweifel, das andere ist, was ich das Fürwahrhalten, die Überzeugung nennen möchte. Man könnte vielleicht auch andere, noch prägnantere Worte finden. Aber Sie alle werden verspüren, daß wir eine Art von polarischem Gegensatz des Seelenlebens haben, wenn wir auf der einen Seite von Zweifel, auf der anderen Seite von Überzeugung sprechen. Stellen Sie sich einmal vor, was da geschieht, wenn in einem intensiveren Umfange den Menschen ergreift, was einerseits im Zweifel und andererseits in der Überzeugung wirkt. Versuchen Sie einmal, sich zu vergegenwärtigen, wie Sie über irgend etwas, und sei es auch nur ein Sie stark in Anspruch nehmendes Ereignis, in Zweifel versetzt sind. Es braucht gar nicht eine große Weltenwahrheit, ein großes Weltenrätsel zu sein, sondern nur eine Sie stark interessierende Angelegenheit. Sie müssen mit diesem Zweifel zu Bett gehen. Stellen Sie sich vor, wie Sie sich herumwerfen, Unruhe empfinden, wie es innerlich rumort und Ihnen keine Ruhe läßt. Und versuchen Sie sich dann zu vergegenwärtigen, wie irgend etwas, was als eine wohltuende Überzeugung in Ihre Seele einfließt, eine innerliche Ruhe bewirkt, wie gewissermaßen eine Seelenwärme Sie ganz erfüllen kann. Kurz, Sie werden, wenn Sie wirklich innerlich die Sache unbefangen betrachten, sich schon die entgegengesetzten Naturen, des Zweifels auf der einen Seite, des Überzeugtseins auf der anderen Seite, vor Ihre Seele stellen können.

Worin liegt der Unterschied in bezug auf die Wesenheit des Menschen? Das menschliche Haupt ist nachgebildet aus dem kosmischen Äther heraus dem, was wir in der geistigen Welt waren, das menschliche Haupt ist eine reine Nachbildung des Allermenschlichsten, nämlich des geistigen Menschen. Zweifelnde Vorstellungen kommen an das Haupt heran, sie finden in dem Haupte keinen Platz. Das Haupt nimmt sie nicht auf. Sie müssen durch das Haupt hindurchgehen bis in die Gliedmaßennatur herunter. In der Gliedmaßennatur, da verbinden sie sich mit alledem, was körnig wird in dem menschlichen Stoffwesen, was so wird, daß es dieses menschliche Stoffwesen körnig durchsetzt, was also eine atomistische Natur annimmt. Zweifelnde Vorstellungen gehen, wie wenn unser Kopf für sie durchlässig wäre, durch ihn hindurch. Das Blut nimmt diese zweifelnden Vorstellungen zunächst auf, dann werden sie hinuntergetragen in den ganzen Organismus, vorzugsweise vom Stoffwechsel aufgenommen, und dann erst dem Nervensystem übergeben, und sie leben in alldem, was in der menschlichen Natur atomistisch ist, was körnig, was salzig ist. Damit verbinden sie sich ganz besonders innig. Der Leib nimmt die Zweifelsvorstellungen auf, durch den Kopf gehen sie durch. Erst wenn man diese besondere Art des menschlichen Hauptes versteht, und daß die Materie des Hauptes nicht geeignet ist für Zweifelsvorstellungen, weil das Haupt ein Abbild der Wahrheit selber ist, aus der wir kommen, wenn wir vom Geistigen ins Physisch-Irdische heruntersteigen, dann begreifen wir: So wie das Licht durch ein durchsichtiges Glas, so gehen durch unseren Kopf die zweifelnden Vorstellungen hindurch und ergreifen den anderen Teil des Nervensystems und rumoren in unserem Stoffwechsel. Der Kopf nimmt die zweifelnden Vorstellungen nur insofern auf, als er selbst Stoffwechselnatur ist. Aber er leitet sie durch seine besondere Nervenorganisation hindurch und nimmt nur die überzeugenden Vorstellungen auf.

Die überzeugenden Vorstellungen finden überall, wenn sie in das Haupt des Menschen eindringen, verwandte Gebilde. Sie finden überall im Nervensystem Unterkunft. Sie lassen sich gleich im Haupte des Menschen nieder und gehen in den übrigen Leib nicht durch das Blut, sondern durch das Nervensystem, das noch dazu in einer Art von Zerstörungsprozeß ist, so daß sie unmittelbar in ihrer Geistigkeit übergehen an den ganzen übrigen Menschen. Aber vorzugsweise finden sie im Kopfe Unterkunft, erfüllen sie den Kopf. Und im Kopf, aus der Geistigkeit der Kopfesform, auch der inneren Formung, bekommen sie ihre für den ganzen Menschen passende Gestaltung und wirken daher so, wie wenn sie mit dem Menschen innig verwandt wären, wie wenn der Mensch selber innerlich in ihnen leben würde, wie wenn sie der Mensch selbst wären. Man möchte sagen: In den überzeugenden Vorstellungen formt das Haupt des Menschen etwas, was dem Menschen besonders angemessen ist.

Studieren Sie den menschlichen Embryo, Sie werden sehen, zuerst bildet sich das Haupt, dann bildet sich der übrige Organismus; denn von dem Haupte gehen diejenigen Kräfte aus, die das übrige bilden. Wenn Sie überzeugende Vorstellungen ins Haupt aufnehmen, so ist es ja geistig so: die werden zunächst im Haupte geistig aufgenommen, und das Haupt sendet sie dann dem übrigen Menschen zu. Wie physisch im Embryo der andere Mensch nachgebildet wird dem menschlichen Haupte, so wird hier das Geistige der Überzeugungen und Vorstellungen des übrigen Menschen ausgestrahlt, und es entsteht ein Mensch daraus auf geistige Weise aus den überzeugenden Vorstellungen (linke Zeichnung, rot). Ein inneres Menschenbild strahlt aus in dem Menschen. Und mit allem, was den Menschen wie Wärme durchzieht, verbindet sich das, was da ausstrahlt an überzeugenden Vorstellungen im Menschen. Wie die zweifelnden Vorstellungen alles Körnige, alles Atomistische ergreifen, so ergreifen die überzeugenden Vorstellungen die den Körper durchströmende Wärme, das erste Glied des Ätherischen, das den ganzen Menschen durchzieht, und gehen nicht weiter ein in das Physische.

Versuchen Sie einmal, so sich die Gegenwart der zweifelnden und der überzeugenden Vorstellungen in der menschlichen Natur vorzustellen, und Sie können jedesmal, wenn Sie das Wohltuende einer überzeugenden Vorstellung, das Folternde von zweifelnden Vorstellungen nachfühlen und erleben, die Wahrheit der Sache im unmittelbaren Leben ergreifen.

Ich habe oftmals gesagt, daß der Sprachgeist ein Geist ist, der vernünftig wirkt. Und wenn man den natürlichen Embryo der Zeugung zuschreibt (Zeichnung rechts, weiß), so ist man gar nicht weiter überrascht, daß jene Bildung hier (links, rot) der Überzeugung zugeschrieben wird. Diese Dinge dürfen wir nicht als bloße Zufälligkeiten ansehen. Sie sind die Taten des waltenden Sprachgenius, der durchaus mehr weiß als der einzelne Mensch. Ich weiß, daß eine heutige linguistische Wissenschaft das als eine Spielerei ansieht. Aber wenn man einmal in das Wirken und Weben des waltenden Sprachgenius wirklich hineinschauen wird, so wird man manches der heutigen Philologie und Linguistik als Spielerei ansehen.

Aber bedenken Sie jetzt, was das Ganze heißt. Sie bekommen ein Bild, wie zwei Seelenerlebnisse, der Zweifel und die Überzeugung, im physischen Menschen weiter wirken. Sie bekommen eine absolut begreifbare Brücke vom Seelisch-Geistigen in das Physische hinüber. Sie sagen sich, hier ist ein physischer Mensch, es schimmert und wellt durch seine physischen Körnchen im Leibe das, was er seelisch-geistig erlebt: das ist ein Skeptiker, das ist ein Zweifler. Sie schen es der inneren Struktur seines Stoffes an, wie da der Zweifelgeist in der Seele, im Körper weiter vibriert. Sie sehen sich den anderen an, bei dem in ruhiger Weise die Wärme durch die Glieder strömt, und Sie sehen in diesem ruhigen Strömen der Wärme den physischen Ausdruck des den Überzeugungen Hingegebenseins. Sie sehen im Menschen einen unmittelbaren physischen Ausdruck des Geistigen. So beginnen Sie erst das Physische zu verstehen. Der heutige Chemiker und Physiker sagt, wenn er den Menschen analysiert: Dadrinnen ist Kalk, Phosphor, Sauerstoff und Stickstoff, Kohlenstoff. — Ja, im Sauerstoff und Stickstoff und Kohlenstoff und Wasserstoff werden Sie niemals ein Geistiges finden. Da hat Du Bois- Reymond selbstverständlich ganz recht, wenn er sagt: Einer Anzahl von Sauerstoff- und Stickstoff- und Kohlenstoffatomen kann es höchst gleichgültig sein, wie sie liegen und sich bewegen. — Ja, wenn man den Stoff im Leibe nur als Kohlenstoff, Sauerstoff und so weiter anschaut, da verhält es sich so. Wenn man aber weiß, wie dadrinnen ein Stoff wirkt, der für den Geist in der verschiedensten Weise empfänglich ist, der im Haupte ein unmittelbares Nachbild von geistiger Wesenhaftigkeit ist, der im übrigen der Erde angegliedert ist, so daß dort das Irdische festhält, was als zweifelnde Vorstellungen durchgetrieben wird durch das Haupt, dann hört die Möglichkeit auf, zu denken, es sei in unserem Gehirn einer Anzahl von Kohlenstoff-, Stickstoffatomen und so weiter gleichgültig, wie sie lagen und sich bewegten, wie sie liegen und sich bewegen. Da sehen wir, wie es dem Stoffe nicht gleichgültig ist, ob sich in ihn der Wärmestrom ergießt, oder ob in ihm die Salzbildung wirksam ist, so daß der Leib die Tendenz bekommt, die körnige Struktur zu entwickeln. Das sind zwei Gegensätze, die sich im Stoffe zum Ausdruck bringen, und die aus dem Geistigen herstammen. Es ist tatsächlich so, daß wir nicht deshalb einen Materialismus im 19. Jahrhundert gekriegt haben, weil man den Geist nicht gekannt hat. Den Geist in seiner filtriertesten Form hat das materialistische Zeitalter am besten gekannt, denn alle früheren Zeitalter haben den Geist eigentlich nicht in Reinkultur gehabt, sie haben in die Bilder des Geistes, die sie sich geformt haben, immer Materielles hineingemischt; es waren Bilder, in die immer Materielles hineingemischt war. Die reinen geistigen Vorstellungen, die hat eigentlich erst das naturwissenschaftliche Zeitalter gebracht. Aber was das naturwissenschaftliche Zeitalter vernachlässigen mußte, das ist gerade die Kenntnis der Materie in Wirklichkeit, des Geistes in der Materie. Was uns in den Materialismus gebracht hat, das ist die zu geringe Kenntnis des materiellen Wesens der Welt, die Einsichtslosigkeit in das geistige Weben und Wirken im Materiellen. Materialistisch ist die Wissenschaft geworden durch Unkenntnis der materiellen Wirkungen. Dadurch, daß man nicht wußte, wie der Geist schöpferisch wirkt, stellte man sich diesen Geist immer abstrakter und abstrakter vor. Dadurch wurde das Sollen, wurden die sittlichen Ideale endlich etwas, wovon man nicht einmal fragen konnte, wo es herumfliegt im Raume, weil es nicht einmal die Materialität hatte, daß es herumfliegen konnte. Es war überhaupt nicht mehr da. Wenn man danach schnappte, war es ungefähr so, wie wenn man in einem Elemente atmen wollte, das nicht da ist. Wie wenn ein Mensch unter dem Rezipienten einer Luftpumpe atmen wollte, so kommen einem die Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts vor! Wenn sie zum Beispiel nach den sittlichen Idealen schnappen — sie sind nicht da; sie möchten sie haben, aber sie sind nicht da, weil man keinen Begriff entwickeln wollte von dem Wirken des Geistig-Seelischen im Physisch-Leiblichen. Daher kamen all die kuriosen Theorien auf von der Wechselwirkung des Physisch-Leiblichen mit dem Seelisch-Geistigen, die alle Gespinste waren, während eine wirkliche Erkenntnis nur durch genaues Eingehen auf den Tatbestand gewonnen werden kann.

Lernt man so kennen, wie der Zweifel, wie die Überzeugung die Menschennatur durchwallen und durchweben, dann ist man imstande, dasjenige, was man am Menschen kennengelernt hat, nun auch wiederum an der Welt kennenzulernen. Wir haben in der Welt die Sphäre des materiellen Schaffens. Wir sehen zum Beispiel, wie sich draußen in der Welt die Materie körnig gestalten muß, wie sie sich kristallisiert. Haben wir erst kennengelernt, wie der Zweifel in uns das Körnige im Organismus ergreift, dann lernen wir draußen den Zweifel schauen. Wir schauen aufden Berg (weiß), der sich mit seinem körnigen Gestein bildet ; aber wir finden zu gleicher Zeit, wie diesen Berg dasselbe durchzieht, was wir in uns als Zweifel kennenlernen (rot), und wir lernen die schöpferische Kraft des Zweifels kennen. Der Zweifel in uns macht uns körnig, weil wir eben Menschen sind und nicht Natur. Der Zweifel draußen in der Natur, der wirkt das Richtige. Wenn das, was draußen in der Natur wirkt, in uns einzieht, so bewirkt es das Unrichtige. Indem Sie auf die Felsen treten, treten Sie auf die physische Ausgestaltung dessen, was die Gottheit als Zweifel aussendet, damit die Welt körnig werden könne. Und wiederum, wenn Sie Ihre Überzeugungen studieren mit dem warmen Durchdrungensein, dann befinden Sie sich in demjenigen, was schöpferisch entsteht. Wenn Sie sich also denken, daß im Grunde genommen in der Wärme der Schoß der schöpferischen Weltenkräfte zu suchen ist, dann finden Sie, daß aus der warmen Materie heraus das wirkt, was kosmische Überzeugung ist.

Lernen Sie diese Dinge erst in Wahrheit in sich kennen, dann lernen Sie auch die Agenzien draußen im Kosmos in der richtigen Weise beurteilen. Wenn Sie dasjenige, was draußen abbröckelt und abbröselt, so daß wir gewissermaßen schon die erste Vorbereitung für das Zerstäuben unseres Irdischen im Weltenall vor uns haben, als Ausstrahlungen des Weltenzweifels ansehen, dann lernen Sie vieles im kosmischen Dasein begreifen. Und umgekehrt, wenn Sie das Überzeugende ins Kosmische hineinzuschauen vermögen, dann lernen Sie vieles von dem Schöpferischen kennen. Doch das sind Dinge, durch die ich Ihnen nur andeuten wollte, wie man erst den Menschen kennen muß, um überhaupt eine Aussicht zu haben, das Weltendasein zu kennen.

Nun, sehen Sie, für Brentano waren in den sechziger Jahren, für Nietzsche in den siebziger Jahren die naturwissenschaftlichen Methoden da; die fanden Kohlenstoff, Wasserstoff, Sauerstoff, Stickstoff, Phosphor, etwas Schwefel und so weiter im Gehirn. Darin war wirklich kein Geistiges zu erkennen. Und wenn man die Methode, die zu diesem geführt hatte, nun auf den Geist anwandte, so konnte man natürlich zu nichts kommen als entweder zu der geistigen Ohnmacht, zu der Brentano gekommen ist, oder zu dem Zermürben des Geistigen, wozu Nietzsche, der mehr Willensnatur war, gekommen ist. Aber beide unterlagen eben dem Schicksal, daß sie nicht vom Physischen zum Geistigen hinkommen konnten, weil sie im Physischen eben das Geistige nicht finden konnten, und daher auch den Geist nicht als etwas empfanden, was mächtig genug ist, um das Physische aus sich hervorzubringen.

So standen solche Geister vor einer physischen Natur, die eigentlich keinen Sinn hatte, weil sie nirgends etwas Geistiges enthält, und vor einer geistigen Natur, die keine Kraft, keine Macht hat. Das ist das Schicksal der bedeutendsten Geister, die in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts und im Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts vor der Materie ohne Sinn, vor dem Geist ohne Kraft standen.

Die Historiker haben von Ideen in der Geschichte gesprochen. Das ist Geist ohne Kraft. Den Ideen können Sie wahrhaftig keine Kulturinstrumente in die Hand geben, durch die die Kultur entsteht, oder durch die überhaupt historische Ereignisse entstehen; Ideen als Abstraktes sind kraftlos, das ist Geist ohne Kraft. Demgegenüber steht die Natur, die man nur in ihrer ungeistigen Materie studiert: Materie ohne Sinn.

Niemals wird man die Brücke finden, wenn man auf der einen Seite das Unding erfindet: Materie ohne Sinn, und auf der anderen Seite den Ungeist: Geist ohne Kraft. Erst wenn man im Geist die Kraft findet, in der Überzeugung die Kraft, die Wärme durch den Körper hindurchzutreiben, weil der Mensch so und so organisiert ist, wenn man in dem Zweifel die Kraft findet, sich durch den Kopf hindurchzudrängen, weil in ihm keine Verwandtschaft mit dem Kopf besteht, und den übrigen Menschen innerlich zu zermürben, so daß er in körnige Strukturtendenz zerfällt, also erst wenn man in dem Geiste dasjenige findet, was Kraft hat, sowohl aufzulösen die körnige Struktur durch die Wärme, wie sie zu bilden in dem Salzbildungsprozeß, dann findet man eine Materie, in der Sinn ist, weil dann der kraftvolle Geist so wirkt, daß eben dasjenige, was in der Materie einem vor Augen tritt, sinnvoll dasteht. Und so haben wir die Materie mit Sinn und den Geist mit Kraft zu suchen.

Das ist es, worauf ganz besonders solche Geister, wie Brentano und Nietzsche, in ihrem tragischen Schicksal, auch in ihren Persönlichkeiten hinweisen.