Notes from Mathilde Scholl 1904–1906

GA 91

(?) 1904, Berlin

Automated Translation

1. The Difference Between Calculation [and] Operation

If we conceive of the relationships between quantities, we have general arithmetic. Special arithmetic deals with specific quantities of units. Algebra is named after “Algeber” (an Arabic mathematician).

First relation between numbers: addition. One number is added to another: \(a + b\) and so on. This is extended to a series:

\(a + b + c + d + e + f\) and so on.

Second relation:

subtraction; you take one number away from another: \(a - b\). This expands: \(a - b - c - d - e\) and so on.

One prerequisite is necessary here, namely that \(a\) is greater than \(b\).

\(a \gt b\) (then \(a\) is greater than \(b\))

\(a = b\) (then \(a\) is equal to \(b\))

\(a \lt b\) (then \(a\) is less than \(b\))

\(c =\) the result: \(a - b = c\).

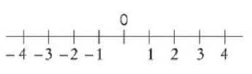

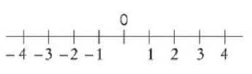

If \(a\) is greater than \(b\), then the question is how much remains if I take away \(b\) from \(a\)? \(c\) remains. \(c\) is the number by which \(a\) is greater than \(b\). If \(a\) is equal to \(b\), then \(c = 0\). If \(a\) is smaller than \(b\), then there is also a \(c\), for example: \(3 - 5 =?\) Here you ask how many units are missing from \(a\) if \(a\) is not as large as \(b\).

| \(3 - 5 = -2\) | \(a - b = -c\) the negative ratio |

|

| \(5 - 3 =\) positive | \(5 - 3 = +2\) | \(a - b = +c\) |

| \(3 - 5 =\) negative | \(3 - 5 = -2\) | \(a - b = -c\) |

[This means: For] a number that is minus, it means: There was a subtraction; in this subtraction, the minuend was too small. — A negative number can only be understood as the result of an arithmetic operation.

The addition can be such that some numbers are equal to each other or all are equal to each other.

\(a + b + a + c\) and so on, or

\(a + a + a + a + a + a\) and so on

If all numbers are equal in the addition, we have multiplication. The number that tells you how many times the same number is in the sum is called the multiplier.

\(a \times b\) means: \(a\) is to be added to \(b\) the same number of times.

or \(a \cdot b\): \(a\) is multiplied by \(b).

\(a \cdot b \cdot c \cdot d\) (means: \(a\) is multiplied by \(b\), \(c\), \(d\) and so on one after the other).

When subtracting, you may subtract different numbers:

\(a - b - c - d - e - f\) and so on, or the same ones, for example \(a - b - b - b - b - b\) and so on.

The question is: how many times can I subtract b from a?

\(a : b\) is division (or a hidden subtraction).

The divisor is actually a minuend. The dividend is actually a subtrahend.

It is a special case of subtraction.

\(a \cdot b \cdot c \cdot d \cdot e \cdot f\)

\(a \cdot a \cdot\) and so on, m times (meaning: the same number multiplied over and over again by itself), is denoted by \(a^m\) (\(a m\) times)

\(a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a\) and so on, multiplied by \(m\) (meaning: the same number multiplied over and over again by itself) is designated by \(a^m\) ( \(a m\) times)

\(a^m = P\) (\(a m\) times taken gives \(P\) = exponentiation).

\(a\) to the mth [power] \(=\) P

\(a =\) the root, the base or the factor.

\(m =\) the exponent.

\(P =\) the power.

The fifth arithmetic operation is exponentiation.

If P and m are known and a is sought:

\(\sqrt[m]{P} = x\) Square root.

abbreviated division:

\(P\) = radicand

\(m =\) root exponent

\(x(a) =\) radix.

If \(m\) is unknown, write \(a^x = P\).

To what power of a do you have to raise a to get \(P\)?

\(x = log_a P\) (the exponent in the parenthesis is the logarithm)

\(2 = log_3 9\) (\(2\) is equal to the log of \(9\) with respect to the root \(3\))

Taking logarithms is the seventh arithmetic operation.

\(a \cdot b\)

\(+a \cdot +b\)

\(+a \cdot +a \cdot +a \cdot +a + b - times\)

\(+a \cdot +b = +ab\)

\(-a \cdot +b = -ab\)

\(+a \cdot -b = -ab\)

\(-a \cdot -b = +ab\)

Multiplying equivalent numbers by each other yields a positive result; non-equivalent numbers yield a negative result.

\(+a \cdot -b = -c\)

\(+a \cdot +b = +c\)

\(-a \cdot +b = -c\)

\(-a \cdot -b = +c\)

Similar numbers divided by each other give a positive result, unlike numbers divided by each other give a negative result.

\(a^b = c\) where \(+a\) and \(+c\)

or \(-a\) and \(+c\)

\(\sqrt[b]{c} = a\)

\((+a)^+b = +c\)

\((-a)^+b = +c\)

\(c\) negative \(= -c\)

\(a^x = -c\)

\(\sqrt[x] - c = a\)

To denote a negative power, imaginary numbers must be found that are neither positive nor negative.

A triangle is a figure bounded by three straight lines. We distinguish triangles according to the size of their sides and their angles. First, we distinguish a triangle in which all three sides are equal, calling it an equilateral triangle, which also has all three angles equal. A triangle in which only two sides are equal and the third unequal is called an isosceles triangle. It has two equal angles, which are adjacent to the unequal side. Then one, which is unequal; all sides and angles are unequal. Size ratios of the angles of a triangle.

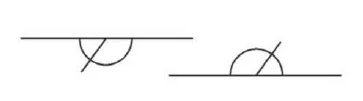

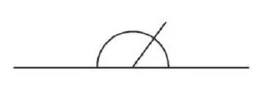

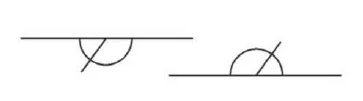

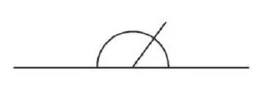

2. Secondary angle

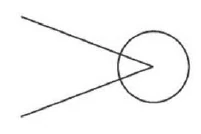

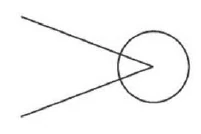

Measuring the angle: The angles are measured according to the relative size of the arc. You measure an angle by drawing a circle around it.

First divide the circle into four parts, then again into two parts, then each of these into five and each of these into \(9\) parts = \(4 \times 2 \times 5 \times 9 = 360°\) (degrees). The angle is as large as the angle is of the \(360°\).

Two minor angles always add up to \(180°\).

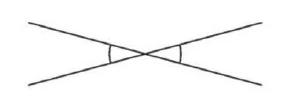

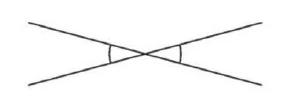

Two vertex angles.

You name the angle by writing a letter in it.

\(\angle a\) is called angle \(a\)

\(\angle a = \angle b\) as vertex angles

\(\angle a + \angle b = 180°\) as an angle between

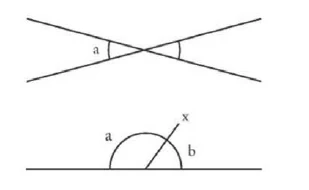

Four pairs of opposite angles

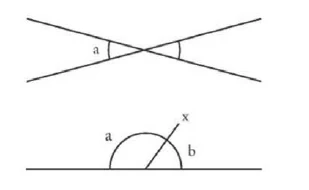

\(x\) the intersecting line

\(y\), \(z\) the lines intersected

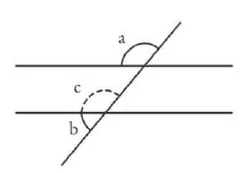

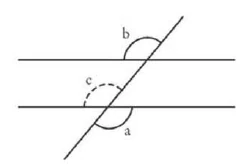

When two straight lines are intersected by a third, four pairs of opposite angles arise, namely those that lie on the same side of the intersecting line and on the same side of the intersected line.

Alternate angles are those that lie on different sides of the intersecting line and on different sides of the line being cut. Four pairs of alternate angles.

Angles are those that lie on the same side of the intersecting line and on different sides of the line being cut. Four pairs of angles.

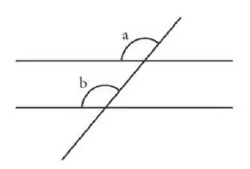

\(a\) and \(b\) are opposite angles.

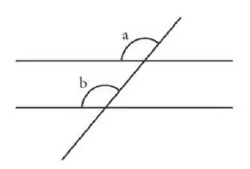

If two parallels are intersected by a third, then the opposite angles are all equal to each other.

\(b\) and \(a\) are alternate angles.

Assume that \(b\) and \(a\) are alternate angles at [two intersecting parallels].

Alternate angles between parallel lines must always be equal.

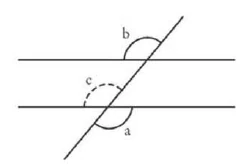

\(b\) and \(a\) alternate angles \(=\) assumption.

Proof:

\((\angle b = \angle c)\)

\(\angle b = \angle c\) as opposite angle

\(\angle a = \angle c\) as vertex angleergo: \(\angle a = \angle b\)

If two quantities of a third are equal, they are also equal to each other.

This is an axiom, on which the proof is based. An axiom is a proposition that is neither capable nor in need of proof.

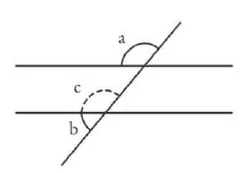

\(a\) and \(b\) are angles.

Proof:

\(\angle a\) and \(\angle b\) are angles (assumption)

\(\angle a = \angle c\) as opposite angle

\(\angle b + \angle c = 180\)° as adjacent angle

ergo: \(\angle b + \angle c = 180°\)

Proof that two angles are always \(180°\).

Axiom: In every calculation, one quantity can be replaced by another equal to it without changing the calculation.

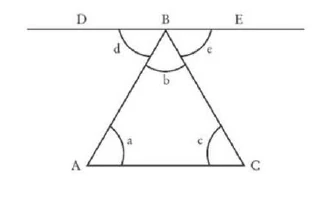

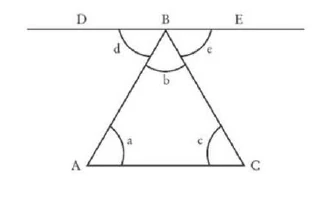

\(ABC\) a triangle (assumption)

\(DE || AC\)

\(\angle a = \angle d\) as alternate angles

\(\angle c = \angle e\) as alternate angles

\(\angle b = \angle b\)

\(\angle d + \angle b + \angle e = 180°\)

ergo: \(\angle a + \angle b + \angle c = 180°\)

The sum of the three angles of any triangle is [\(180°\)].

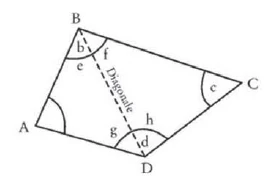

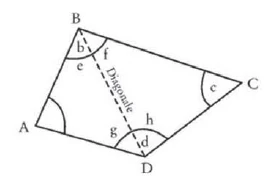

\(A B C D\) quadrilateral. Given

\(\angle e + \angle a + \angle g = 180°\)

\(\angle f + \angle h + \angle c = 180°\)

\(\angle c + \angle a + \angle g + \angle f + \angle h + \angle c = 360°\)

\(\angle a + \angle b + \angle d + \angle c = 360°\)

ergo: In every quadrilateral, the sum of the \(4\) angles is \(360°\)

Line: spatial size of one dimension - length

Area: spatial size of two dimensions - length + width

Body: spatial size of three dimensions - length + width + thickness

?

Spatial size of four dimensions

A two-dimensional space is bounded by a surface. A right angle has a quarter of a circular arc between its legs.

A square is a surface that is bounded by four equal lines and has four right angles.

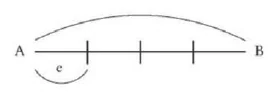

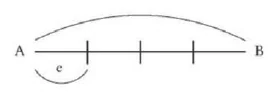

Line with four units of measurement, \(e\) one unit of length, \(ab = 4 \times e\) (\(4 \times\) the unit), \(A B = 4 \times e\)

You can measure a length by counting how many times the unit is included.

\(e\) (size \(e\)) squared is the unit area. The unit area is a c described in terms of the unit length.

Area unit. Question: How much larger than the area unit is the whole square when the side is four times larger than the length unit?

\(A B C D = AB^2\)

The area of a square is found by multiplying one side by itself and raising it to the power of two.

\(1^2 = 1\)

\(2^2 = 4\)

\(3^2 = 9\)

\(4^2 = 16\)

\(5^2 = 25\)

\(6^2 = 36\)

\(7^2 = 49\)

\(8^2 = 67\)

\(9^2 = 81\)

\(10^2 = 100\)

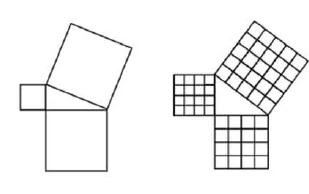

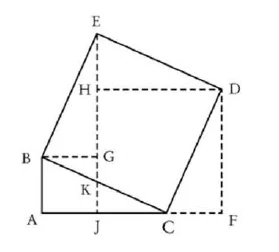

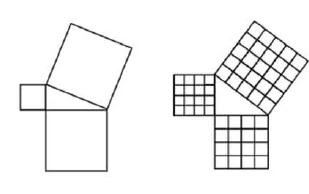

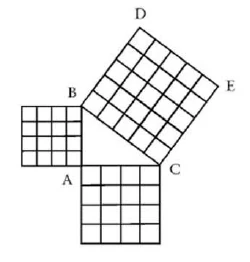

The two sides of a right angle form the cathets. The opposite line is the hypotenuse.

\(3^2 = 4^2 = 5^2\)

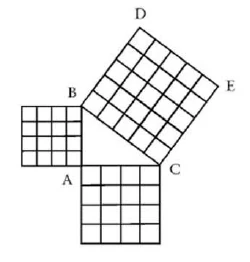

\(BDEC = BC^2\)

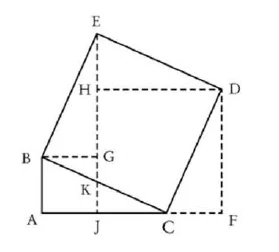

\(HEFJ = \angle ABC + HJCE\)

\(CE =BC\)

\(HEFJ = \angle ABC + HJCE\)

\(CE =BC\)

\(ABC = BDG\)

\(JKC = BGK\)

\(BDEC = BGHECB + BGD + HCE\)

\(HEFJ = HJCE + CEF\)

\(HJGB = HBJK + BGK\)

\(HJCE + EEF + BGK + ABKJ =\)\(BGHECJKB + ABC + ABKJ\)

\(BGHEC + ABC + ABJK + JKC\)

\(BEDC = BC^2\)

\(BGE = DCF\)

\(EHD = BAC\)

\(BKCDHG = BKCDHG BGK = JKC\)

therefore

\(BKCDHG + ABC + DFC =\)

\(KKCDHG + BGE + EHD\)

\(EB = BC\), \(ED = BC\), \(CD = BC\)

\(ABC\), \(BGE\), \(EHD\), \(DFC\) are right triangles on equal hypotenuses, and therefore equal, since all the angles correspond; therefore, triangle \(EGB = DCF\) and \(EHD = ABC\); [illegible] \(BGHD:CK\) is equal to itself.

1. Unterschied Zwischen Rechnung [und] Operation

Wenn wir die Beziehungen zwischen Größen auffassen, haben wir allgemeine Arithmetik. [Die] besondere Arithmetik beschäftigt sich mit bestimmten Mengen von Einheiten. Algebra ist nach «Algeber» (arabischem Mathematiker) benannt.

Erste Beziehung zwischen den Zahlen: Addition. Eine Zahl wird um die andere vermehrt: \(a + b\) und so weiter. Dies wird auf eine Reihe ausgedehnt:

\(a + b + c + d + e + f\) und so weiter.

Zweite Beziehung:

Subtraktion; man nimmt von einer Zahl eine andere weg: \(a - b\). Dies erweitert: \(a - b - c - d - e\) und so weiter.

Eine Voraussetzung hierbei ist notwendig, nämlich dass \(a\) größer ist als \(b\).

\(a \gt b\) (dann ist \(a\) größer als \(b\))

\(a = b\) (dann ist \(a\) gleich b)

\(a \lt b\) (dann ist \(a\) kleiner als \(b\))

\(c =\) das Resultat: \(a - b = c\).

Wenn \(a\) größer ist als \(b\), dann ist die Frage, wie viel bleibt übrig, wenn ich \(b\) von \(a\) wegnehme? \(c\) bleibt übrig. \(c\) ist die Zahl, um welche a größer ist als \(b\). Wenn \(a\) gleich \(b\) ist, dann ist \(c = 0\). Wenn \(a\) kleiner ist als \(b\), dann bleibt auch ein \(c\), zum Beispiel: \(3 - 5 = ?\) Hierbei fragt man, wie viele Einheiten fehlen dem \(a\), wenn \(a\) nicht so groß ist wie \(b\).

| \(3 - 5 = -2\) | \(a - b = -c\) das negative Verhältnis |

|

| \(5 - 3 =\) positiv | \(5 - 3 = +2\) | \(a - b = +c\) |

| \(3 - 5 =\) negativ | \(3 - 5 = -2\) | \(a - b = -c\) |

[Das bedeutet: Für] eine Zahl, die minus ist, heißt [das]: Es lag eine Subtraktion vor; bei dieser Subtraktion war der Minuend zu klein. — Eine negative Zahl kann man nur als Ergebnis einer Rechnungsoperation verstehen.

Die Addition kann so sein, dass einige Zahlen einander gleich sind oder alle sich gleich sind.

\(a + b + a + c\) und so weiter, oder

\(a + a + a + a + a + a\) und so weiter

Wenn bei der Addition alle Zahlen einander gleich sind, haben wir Multiplikation. Die Zahl, die sagt, wie oft die gleiche Zahl steht, heißt Multiplikator.

\(a \times b\) heißt: \(a\) ist \(b\) mal zu addieren.

oder \(a \cdot b\): \(a\) ist mit \(b\) zu multiplizieren.

\(a \cdot b \cdot c \cdot d\) (heißt: \(a\) wird mit \(b\), \(c\), \(d\) und so weiter nacheinander multipliziert.)

Bei der Subtraktion kann es sein, dass man verschiedene Zahlen abzieht:

\(a - b - c - d - e - f\) und so weiter, oder gleiche, zum Beispiel \(a - b - b - b - b - b\) und so weiter.

Die Frage ist: Wie oft kann ich b von a abziehen?

\(a : b\) ist Division (oder eine versteckte Subtraktion)

Der Divisor ist eigentlich ein Minuend. Der Dividend ist eigentlich ein Subtrahend.

Es ist ein spezieller Fall der Subtraktion.

\(a \cdot b \cdot c \cdot d \cdot e \cdot f\)

\(a \cdot a \cdot\) undso weiter, m mal (heißt: dieselbe Zahl immer wieder mit sich selbst multipliziert), wird bezeichnet durch \(a^m\) (\(a m\) mal)

\(a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a \cdot a\) und so weiter, \(m\) mal (heißt: dieselbe Zahl immer wieder mit sich selbst multipliziert), wird bezeichnet durch \(a^m\) ( \(a m\) mal)

\(a^m = P\) (\(a m\) mal genommen gibt \(P\) = Potenzierung.)

\(a\) zur mten [Potenz] \(=\) P

\(a =\) Wurzel, Grundzahl oder Basis.

\(m =\) der Exponent.

\(P =\) die Potenz.

Die fünfte Rechnungsoperation ist Potenzieren.

Wenn P bekannt ist und m bekannt ist und a gesucht wird:

\(\sqrt[m]{P} = x\) Radizieren oder Wurzel ziehen.

abgekürztes Dividieren:

\(P\) = Radikant

\(m =\) Wurzelexponent

\(x(a) =\) Radix

Wenn \(m\) unbekannt ist, schreibt man \(a^x = P\).

Zu welcher Zahlpotenz muss man a erheben, um \(P\) zu bekommen?

\(x = log_a P\) (eingerückter Exponent ist Logarithmus)

\(2 = log_3 9\) (\(2\) ist gleich log von \(9\) in Bezug auf die Wurzel \(3\))

Logarithmieren ist die siebte Rechnungsoperation.

\(a \cdot b\)

\(+a \cdot +b\)

\(+a \cdot +a \cdot +a \cdot +a + b - mal\)

\(+a \cdot +b = +ab\)

\(-a \cdot +b = -ab\)

\(+a \cdot -b = -ab\)

\(-a \cdot -b = +ab\)

Gleichwertige Zahlen miteinander multipliziert geben ein positives Resultat; ungleichwertige geben ein negatives Resultat.

\(+a \cdot -b = -c\)

\(+a \cdot +b = +c\)

\(-a \cdot +b = -c\)

\(-a \cdot -b = +c\)

Gleichartige Zahlen durch einander dividiert geben ein positives, ungleichartige durch einander dividiert geben ein negatives Resultat.

\(a^b = c\) where \(+a\) und \(+c\)

oder \(-a\) und \(+c\)

\(\sqrt[b]{c} = a\)

\((+a)^+b = +c\)

\((-a)^+b = +c\)

\(c\) negative \(= -c\)

\(a^x = -c\)

\(\sqrt[x] - c = a\)

Um eine negative Potenz zu bezeichnen, müssen imaginäre Zahlen gefunden werden, die weder positiv noch negativ sind.

Ein Dreieck ist eine von drei geraden Linien begrenzte Figur. Man hat zu unterscheiden die Dreiecke nach Größe ihrer Seite und ihrer Winkel. Wir unterscheiden zunächst ein Dreieck, bei dem alle drei Seiten gleich sind, nennen es gleichseitiges Dreieck, das auch alle drei Winkel gleich hat. Ein Dreieck, bei dem nur zwei Seiten gleich sind und die dritte ungleich, heißt gleichschenkliges Dreieck. Es hat zwei Winkel gleich, die der ungleichen Seite anliegen. Dann eins, das ungleichseitig ist; dabei sind alle Seiten und Winkel ungleich. Größenverhältnisse der Winkel eines Dreieckes.

2. Nebenwinkel

Messen des Winkels: Die Winkel werden gemessen nach der verhältnismäßigen Größe des Kreisbogens. Man misst einen Winkel, indem man um den Winkel einen Kreis zieht.

Man teilt den Kreis zuerst in vier Teile, dann nochmal in zwei Teile, dann jeden derselben in fünf und davon jeden in \(9\) Teile = \(4 \times 2 \times 5 \times 9 = 360°\) (Grad). So viel der Winkel von den \(360°\) hat, so groß ist er.

Zwei Nebenwinkel machen immer zusammen \(180°\).

Zwei Scheitelwinkel.

Man benennt den Winkel, indem man einen Buchstaben hineinschreibt.

\(\angle a\) heißt Winkel \(a\)

\(\angle a = \angle b\) als Scheitelwinkel

\(\angle a + \angle b = 180°\) als Nebenwinkel

Vier Paar Gegenwinkel

\(x\) die schneidende Linie

\(y\), \(z\) die geschnittenen Linien

Wenn zwei gerade Linien von einer dritten geschnitten werden, so entstehen vier Paar Gegenwinkel, nämlich solche, die auf derselben Seite der schneidenden und auf derselben Seite der geschnittenen Linie liegen.

Wechselwinkel sind solche, die auf verschiedenen Seiten der schneidenden und auf verschiedenen Seiten der geschnittenen Linien liegen. Vier Paar Wechselwinkel.

Anwinkel sind diejenigen, welche auf derselben Seite der schneidenden und auf verschiedenen Seiten der geschnittenen Linie liegen. Vier Paar Anwinkel.

\(a\) und \(b\) sind Gegenwinkel

Wenn zwei Parallele von einer dritten geschnitten werden, so sind die Gegenwinkel alle einander gleich.

\(b\) und \(a\) sind Wechselwinkel.

Voraussetzung sei: \(b\) und \(a\) seien Wechselwinkel bei [zwei geschnittenen Parallelen].

Wechselwinkel zwischen parallelen Geraden müssen immer einander gleich sein.

\(b\) und \(a\) Wechselwinkel \(=\) Voraussetzung.

Beweis:

\((\angle b = \angle c)\)

\(\angle b = \angle c\) als Gegenwinkel

\(\angle a = \angle c\) als Scheitelwinkelergo: \(\angle a = \angle b\)

Wenn zwei Größen einer Dritten gleich sind, sind sie auch untereinander gleich.

Dies ist ein Axiom, worauf sich der Beweis stützt. Ein Axiom ist ein Satz, der eines Beweises weder fähig noch bedürftig ist.

\(a\) und \(b\) sind Anwinkel

Beweis:

\(\angle a\) und \(\angle b\) sind Anwinkel (Voraussetzung)

\(\angle a = \angle c\) als Gegenwinkel

\(\angle b + \angle c = 180\)° als Nebenwinkel

ergo: \(\angle b + \angle c = 180°\)

Beweis, dass zwei Anwinkel immer \(180°\) sind.

Axiom: In jeder Rechnungsoperation kann eine Größe durch eine ihr gleiche ersetzt werden, ohne dass in der Rechnungsoperation dadurch etwas geändert wird.

\(ABC\) ein Dreieck (Voraussetzung)

\(DE || AC\)

\(\angle a = \angle d\) als Wechselwinkel

\(\angle c = \angle e\) als Wechselwinkel

\(\angle b = \angle b\)

\(\angle d + \angle b + \angle e = 180°\)

ergo: \(\angle a + \angle b + \angle c = 180°\)

Die Summe der drei Winkel eines beliebigen Dreiecks ist [\(180°\)].

\(A B C D\) Viereck. Voraussetzung

\(\angle e + \angle a + \angle g = 180°\)

\(\angle f + \angle h + \angle c = 180°\)

\(\angle c + \angle a + \angle g + \angle f + \angle h + \angle c = 360°\)

\(\angle a + \angle b + \angle d + \angle c = 360°\)

ergo: In jedem Viereck ist die Summe der \(4\) Winkel \(360°\)

Linie: Raumgröße von einer Dimension - Länge

Fläche: Raumgröße von zwei Dimensionen — Länge + Breite

Körper: Raumgröße von drei Dimensionen - Länge + Breite + Dicke

?: Raumgröße von vier Dimensionen

Ein zweidimensionaler Raum abgegrenzt ist eine Fläche. Ein rechter Winkel hat zwischen den Schenkeln ¼ Kreisbogen.

Ein Quadrat ist eine Fläche, die begrenzt ist von vier gleichen Linien und die vier rechte Winkel hat.

Linie mit vier Maßeinheiten, \(e\) eine Längeneinheit, \(ab = 4 \times e\) (\(4 \times\) die Einheit), \(A B = 4 \times e\)

Man kann eine Länge messen, indem man ausmisst, wie oft die Einheit darauf enthalten ist.

\(e\) (Größe \(e\)) zum Quadrat ergänzt ist Flächeneinheit. Flächeneinheit ist ein c, das über die Längeneinheit beschrieben ist.

Flächeneinheit. Frage: Wievielmal größer als die Flächeneinheit ist das ganze Quadrat, wenn die Seite viermal größer ist als die Längeneinheit?

\(A B C D = AB^2\)

Man findet die Fläche eines Quadrates, indem man eine Seite mit sich selbst multipliziert und zum Quadrat erhebt.

\(1^2 = 1\)

\(2^2 = 4\)

\(3^2 = 9\)

\(4^2 = 16\)

\(5^2 = 25\)

\(6^2 = 36\)

\(7^2 = 49\)

\(8^2 = 67\)

\(9^2 = 81\)

\(10^2 = 100\)

Die zwei Seiten eines rechten Winkels bilden die Katheten. Die gegenüberliegende Linie ist die Hypotenuse.

\(3^2 = 4^2 = 5^2\)

\(BDEC = BC^2\)

\(HEFJ = \angle ABC + HJCE\)

\(CE =BC\)

\(HEFJ = \angle ABC + HJCE\)

\(CE =BC\)

\(ABC = BDG\)

\(JKC = BGK\)

\(BDEC = BGHECB + BGD + HCE\)

\(HEFJ = HJCE + CEF\)

\(HJGB = HBJK + BGK\)

\(HJCE + EEF + BGK + ABKJ =\)\(BGHECJKB + ABC + ABKJ\)

\(BGHEC + ABC + ABJK + JKC\)

\(BEDC = BC^2\)

\(BGE = DCF\)

\(EHD = BAC\)

\(BKCDHG = BKCDHG BGK = JKC\)

folglich

\(BKCDHG + ABC + DFC =\)

\(KKCDHG + BGE + EHD\)

\(EB = BC\), \(ED = BC\), \(CD = BC\)

\(ABC\), \(BGE\), \(EHD\), \(DFC\) sind rechtwinklige Dreiecke auf gleichen Hypotenusen, folglich gleich, da alle Winkel sich entsprechen; folglich Dreieck \(EGB = DCF\) und \(EHD = ABC\); [unleserlich] \(BGHD:CK\) ist sich selbst gleich.