What is the Purpose of Anthroposophy and the Goetheanum?

GA 84

15 April 1923, Dornach

Automated Translation

The Soul Life of Man and its Development Towards Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition

Yesterday I tried to look at the essence of man and the essence of human life from the point of view that arises when human life in its completeness is placed before the soul. I said that this human life does not only flow during the waking hours, but that about one third of the entire human life flows during sleep. And initially, if we consider only the ordinary human consciousness, we stand before this human life in such a way that when we look back into our earthly existence in terms of memory, we actually only ever remember the days, those times of our life that we spend awake. We always overlook, so to speak, that which takes place in the time that we have slept through. Now, however, it must be said: For what we have to create outwardly for earth culture, earth life, our waking day life comes into consideration; but it is a question of whether only those ideas come into consideration that take place in the waking day life before the ordinary consciousness.

That this is not the case can already be taught by a superficial consideration. Only those considerations which I want to make today and in the last days of this week will show that the events which the human soul experiences from falling asleep to waking up remain hidden, but that these events are still incomparably more important for the inner being of the human being on earth than the events which take place during the day.

Today, in continuation of what was said yesterday, we first want to consider some things which again result from a comparison of the sleeping life and the ordinary waking life. The life of sleep takes place partly in complete dreamless sleep. The time we spend with our earthly life during this dreamless sleep, if it contains events for our life, is completely unconscious. From this unconsciousness, from this complete darkness of consciousness, dreams then emerge, and from dreams we either wake up to ordinary consciousness, in that earthly reality is given to us through sensory perception and through the combination of the intellect, or we also sleep from this reality through the dream into dreamless consciousness.

Let us once again make it clear to ordinary external observation what the difference is between dreaming and external sensory observation, which lives in images and concepts of the mind.

We can say that for many people dreams often contain a more vivid reality than that which takes place in waking daily life. But this is a pictorial reality that we do not follow with our will, but inevitably with our soul. And we can precisely indicate the difference between following these dream images and following the ordinary reality images of waking daily life. We do not want to get involved in particular philosophical speculations. These could also be made, but we will refrain from them now. We only want to look at what the very popular consciousness gives us. We can say that the dream images are such that we live in them. We live in the images themselves. We live with the images. In waking daytime life we naturally have color images, sound images and so on before us in the same way as in dreaming experience. But we are compelled to relate these images, be they facial images, sound images, thermal images, tactile images and so on, to a certain extent to hard reality. We see everywhere in day-to-day reality the need to come up against what the image shows us with our will, so to speak.

This is not the case with, well, let's say dream reality. Dream reality is, if I may put it crudely, to be penetrated everywhere. We can only find the point of view from which we judge the significance of dream reality within waking daily life. As long as we dream, we consider the dream to be reality, and if we were to dream our whole life, dream reality would be the only reality for us. We need not imagine that outer life would then be different from what it is now. We could imagine that individual human beings would not meet in life through their own will, but would be pushed towards each other as if automatically by natural forces or pushed towards each other by some higher being. We could also imagine that people are driven to their work, pushed by higher beings or by forces of nature. In short, everything that happens to us in waking life could happen. We don't need to know anything about it. If we were only dreaming, we would have a dream reality before us. It would not occur to us to want to somehow break through this reality to another reality. We wake up through the natural organization of our organism and then gain the viewpoint within sensory reality to judge the other relative reality value of the dream.

So it is only when we go through this life-jolt from dreaming to waking that we gain the point of view to judge the relative reality value of the dream.

But we must now ask ourselves: Is everything that we experience during daytime waking really a waking state? Well, yesterday I explained in detail that this is not the case. I explained in detail that actually only our imaginations, but these only in so far as they depict external reality, bring us into wakefulness. So that we are actually only awake in our imaginations. In our feelings we have no other reality before us with regard to the state of the soul than in dreams; only that the dream appears to us in images, the feelings in that indeterminacy with which they emerge from the depths of the life of the soul.

However, if one is not an ordinary psychologist who forges everything according to some preconceptions, but if one approaches the emotional content of the soul with impartial observation, one sees how the feelings, which, if I may put it this way, shoot up against the life of imagination, show a blurring, a fluctuating merging like the dream images. We also dream with feeling when we are awake. Only because, I would like to say, the substance in which the dream images appear is different from the substance of the feelings, we do not come to the conclusion that actually all feeling has only the meaning of reality that the dream also has. So that, while we are really imagining while awake, our imaginations are continually flooded with the indeterminate subjective contents of feeling.

Imagine vividly how, on waking, the dream images play into the waking consciousness of the day, how in the dream images everything is fluctuatingly enlarged, diminished - as the case may be - so you will be able to say to yourself: Something comes, seemingly naturally, to the human being in images, which otherwise comes to the human being in the emotional life, again blurred, subjectively enlarging, reducing things, from within.

And with regard to our volition, we are also in deep sleep when awake. We only know the intentions of our will. But these are thoughts, ideas. If I want to go for a walk, I first have the idea of going for this walk. This is my intention. Ordinary consciousness shows just as little of how this intention constantly enters my organism as it shows what passes from falling asleep to waking up. Again, I can only measure the success by the movement that I make, by the change in the aspects that appear before me when I take the walk - in other words, again by ideas. What actually takes place in the organism between the idea of the intention and the idea of success, I sleep through for the ordinary consciousness just as I sleep through what takes place from falling asleep to waking up.

So we can say that man is willing, even when he is awake, in a deep dreamless sleep, that he is sentiently dreaming, even when he is awake, and that he is only awake in a certain way when he lives in ideas. But if man really looks honestly within himself, he realizes that these ideas are only awake in relation to external nature, not in relation to their own life. In relation to his own life of imagination, man cannot come to a real wakefulness. One only has to be clear about the fact that for most people, if they cannot imagine anything external, imaginative activity no longer exists at all. But that is actually only because, especially in today's culture, man is devoted to the outside world, so that we can compare this devotion to being in a roaring, roaring world.

Imagine someone here playing the piano or some instrument, and out there the machines are roaring in a quite extraordinary way. You would hear the machines. You would hardly be able to hear the piano, especially if you were a little further away from it. Basically, it is the same with what actually lives inside the human being from the activity of thinking. But we have to use the comparison correctly. When we learn external natural science today, when we absorb all the concepts that are brought to man in the external theory of evolution, then it is basically a din of thought, a noise of thought. And this noise of thinking, which today's man indulges in, especially if he is a scientist, disturbs his finer perception of inner thinking activity. That is why he sleeps through the inner activity of thinking.

In my “Philosophy of Freedom” I referred to this pure thinking, which does not think something external, but which runs entirely within the human being. But I am also aware that with this pure thinking I have actually described something of which many of our contemporaries say that it does not exist; just as someone who hears the roar of machines out there and not the piano would say that it does not exist.

But if this is so, we can see something extraordinarily important from it, namely that we are actually only awake for thinking, insofar as it has an external natural content, but that we are at most dreaming with regard to the inner activity that we accomplish there. Moreover, we dream the feelings and sleep through the will. Thus the activity of the soul, that which lives within us, is basically not awakened when we are awake to the sense world. We continue to sleep, even during daytime waking, for our thinking activity, for feeling, for willing. We only wake up for external nature. And this waking up is something we are still developing through instruments, through experimental methods, and thereby arrive at the meaningful natural science of the present. This must come into being by reflecting the external processes in our ideas, so to speak. But we do not wake up to the same extent for our thinking, feeling and willing. And whoever can observe impartially how the dream actually differs from the outer physical-sensual world of perception, will not find the life of the soul according to thinking, feeling and willing similar to that which outer sensual perceptual impressions are, but will at most find this life of the soul similar to its most significant element, dreaming. With regard to the content of our soul, we are actually dreaming and sleeping all the time. We only wake up to the content of nature. We do not wake up at all to the content of our soul in ordinary consciousness, we sleep gently away. And as we said, the dream images are, so to speak, such that one can penetrate them, that they do not rest on a hard external reality that is subject to the will. But our soul content is also like that. It lives in images. And anyone who has the ability to compare qualities, not just quantities, will find that if he attributes pictorial character to the dream content, which initially does not point to a reality, he must also attribute pictorial character to the content of his own soul.

But then a meaningful question arises from this. If I live in dreams, I wake up to physical reality, then feel connected to physical reality as a reality by the fact that I am switched on with my will in my body, and from the point of view of this physical reality I attribute to the dream at most a relative, a completely different reality.

Can I now - so the question is - wake up to the life of the soul in the same way as I wake up to nature? Can I switch myself on, just as I switch the dream images into what is the structure of reality through my will, which I press into my body, can I also switch thinking, feeling and willing into a corresponding reality through a higher awakening? This, you see, is the question: Can I wake up to the life of the soul in the same way as I wake up to nature? The content of nature, which I experience as a human being during my earthly existence with the outer physical-sensual reality, appears to me pictorially in my dreams. But the whole life of the soul also only appears to me pictorially as in a dream. So, can I wake up to the life of the soul?

Yes, you can wake up. One can awaken by first sharpening and internalizing one's thinking through such exercises as I have given in the book “How to Gain Knowledge of the Higher Worlds” and in my “Secret Science”, by not merely allowing oneself to be stimulated to a thought content from outside, but by giving oneself a manageable thought content, which is not suggested to one, from within, then resting on this thought content, concentrating on such a thought content actively given to the soul from within. In this way, one gradually arrives at the real consciousness of thinking.

You do not have the consciousness of thinking at all if you only allow yourself to be stimulated for the ideas from the outside. Only if one stimulates oneself to think from within again and again through meditation, through concentration on the content of thought, then one becomes aware of oneself within thinking. Then you realize that you actually live in this thinking, but that you only don't know it when you allow yourself to be stimulated from the outside. Thinking becomes alive in this way, whereas otherwise it is abstract and dead. Thinking becomes something that does not merely exist in the shadows of thought that we receive from outside, but something that stirs inwardly like the blood of the soul. One becomes as if filled with a second humanity.

The thoughts become living forces, image forces, as I have also called them in my book “Theosophy”. And one becomes aware that one actually carries thinking within oneself as a second body, as the etheric body, as the body of formative forces; for one becomes aware that that which otherwise exists only shadowed in thoughts is actually the same forces that bring about our growth. One withdraws into the growth of one's human being, and one comes to realize how that which would otherwise proceed merely chemically as processes according to the peculiarities of the substances we absorb is processed through the same inner spiritual corporeality, etheric corporeality, which forms our thoughts, how we become a unified inner human being through these inwardly living, stimulating thoughts. In this way, we get to know a second person within ourselves.

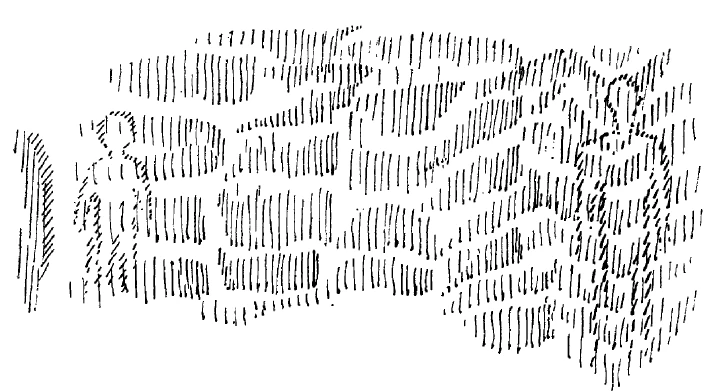

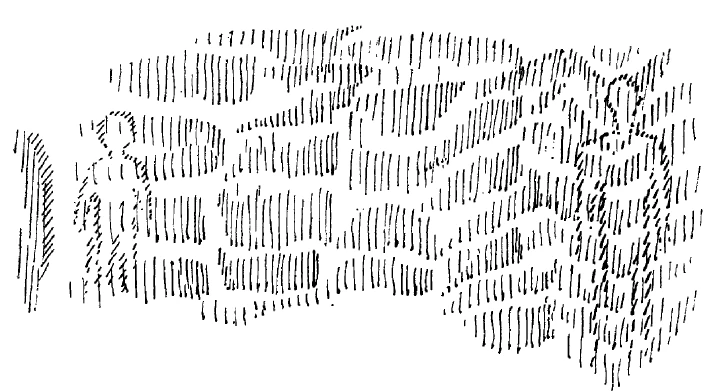

But you also come to something else. This second person, whom we get to know, is not merely a cloud that fills the physical body in a vague way. This second person is actually in constant motion, and it is not possible to hold him in one moment. You see, it is actually like this: if we have the physical body of the human being in a certain point of life, then we can draw what we experience in this way, and what is identical with our thinking - only that in ordinary thinking we have the shadows of thoughts, not the living thoughts themselves - for a moment there (see drawing). What pervades the human being as such a second etheric or visual force body can only be captured for a moment. In the previous moment it was quite different; in the next moment it will be different again, and so on backwards and forwards.

But this leads to the conclusion, if one comes to it in the inner, contemplative experience, that this body of formative forces, which for the ordinary consciousness expresses itself as the shadowy abstract thoughts, is nothing spatial at all, that it is something that runs in time. This leads us back as a living tableau to a certain moment of our first childhood. I will now draw this schematically. \

Imagine that we are already an older person in this time; but this pictorial body of forces is not limited to one time, but leads back to our childhood. We do not view our life in terms of memories, but like a tableau all at once. What I am drawing here spatially is temporal. This now leads back to our childhood, to the time in our childhood up to which we usually remember.

There is now also this etheric body, this body of imagery. But if, through careful practice, you acquire the ability to look back to that point, then you reach the point where you learned to think as a small child. It is as if one reaches a limit with thinking, at first with ordinary thinking. For ordinary consciousness, for ordinary memory, you reach this limit. In the imagination you come further back to the other side. One looks into the soul content of the child that one had when one was not yet able to think, when one dreamed oneself into the world as a child. For it was only at a certain moment that thinking occurred, namely after speaking.

Now you can see into time, see what it was like in the soul before you had the shadowy abstract thoughts. Then we still had living thinking. And living thinking had a powerful plasticizing effect on the human brain, on the entire human organization. Later, when much of this thinking is taken into the abstract, into the dead, there are only remnants left to work on the human physical organization. While one is dreaming as a child, not yet able to think, thinking is active. Precisely because in later life one cannot look at such thinking through the noise of the world, it does not happen at all that one looks back into the thinking that was still active. Now one can look back. And then this thinking appears as the sum of the forces that actually built you up as a human being, as forces of growth, as forces of nourishment and so on. One notices how the human organization is built out of the ether of the world, for these forces lie within it. You get closer and closer to the etheric body. One knows how this etheric body is most active from the outside into the child in the very first years, when the child cannot yet think, when it still spends its life dreaming. This is how one advances to the imagination.

But something can remain. You don't realize it if you don't do the exercises I've mentioned in the books I've mentioned in the face of today's culture, which is roaring with scientificity. But then you realize that something has remained of this thinking from the other side, as you had it as a small child. This thinking, which is constructive, formative for the organism, to which one owes one's outer physical organism in the first place, this lively thinking I have called imaginative thinking in my books. But something of this imaginative thinking remains with you, and through practice you can also explore it again in later life, so that you can approach the etheric body.

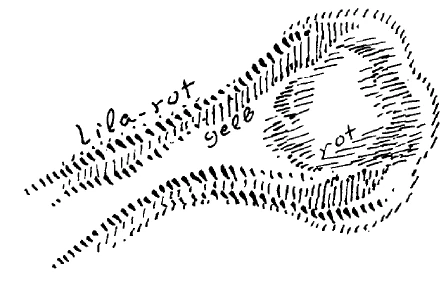

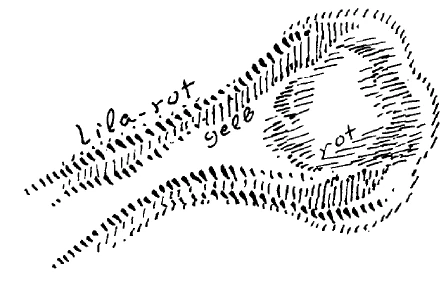

I already drew attention to this yesterday, but since not everyone was there, I would like to point it out again: Take the human eye, the optic nerve of the human eye, which goes inwards, spreads out in the eye. If you go so far with the visual force body (purple-red), which essentially follows the outer physical nerve processes (yellow), that you come close to those processes (red) where the outer world is reflected through the eye, then you have perception of the outer world. And what then establishes itself in the nerve - I will now only describe this approximately, it would take too much time if I were to describe the exact process - that which establishes itself through the nerve in the body of visual forces can then always be stimulated to activity again. With the activity of the body of visual forces, the nervous system, one reaches the point where the nerves end (yellow). One does not, so to speak, penetrate the nerve as far as the processes that reflect the outer world, one only gives an impulse to that which lives in them in the formative forces body, pushes this formative forces body to where the nerve stumps end, then one receives the memory impression. The memory impression consists essentially in the fact that one reaches the nerve endings with the inner activity; while for the sensory impressions one pushes through the nerve endings and advances to the processes in the senses that are mainly caused by the blood.

There you see the living activity of the body of formative forces. But everything that you push into memory must have entered the nervous system, so it has only been there since we learned to think as a very small child. What was there before is now so - and if one has now trained the mind through exercises and looks back, one sees this in retrospect through the temporally passing second human being -: There one becomes aware of how, on the same paths on which otherwise the impressions entering from outside turn around again through the memory in the memory faculty, how that which is now also the activity of the body of formative forces comes in from behind, so to speak. We actually have these two activities all the time. But in ordinary consciousness man knows only of the one, of memory. But one has these two activities: That which stems from the external sensory perceptions, which are pushed back and can in turn be pushed forward to the nerve stumps, so that the memory images emerge; but there is also something that pours into the whole nervous system from that side, so to speak, in a human-creative way, where one does not perceive sensually with the same strength as on the front of the body.

The creative forces enter the human being from behind - of course, this is not entirely accurate - but from behind: In early childhood, when one is not yet able to think, quite powerful, later weaker. This is the thinking that is not taken from the sensory world, that is taken from the entire universe, that is taken from the world ether, that we acquire by descending from pre-earthly existence into earthly existence, that we still retain superhumanly until the moment when we learn to think. At the moment when we learn to think, we close the door, so to speak, to this active thinking, to this development of the human formative forces in the formative body, in the etheric body, according to the continuous stream of our life. Learning to think for the outer sense world means closing the gate for the universal world-forming powers of thought.

When we were children, we closed the gate for the world-forming powers of thought. But they remain in us, because we need these formative forces continuously in the first period of our lives, as long as we are growing as growth forces, and later as the processing forces for what we absorb as nourishment and so on. But we do not notice them. We only notice that which is reflected by the formative forces in the body from the impressions we have absorbed, which then reach the nerve endings in the memories.

But through exercises in concentration and meditation we can become aware of that which now forms us from the world etheric. In our self-perception we become aware of processes which also take place in time, which we have not absorbed through external impressions, but which only have a flow to one side. If we then follow these up to the point where the nerves run out, where we otherwise have the memories of external impressions, then we not only get the image of our etheric body, but the image of how we as human beings are contained within the entire world ether. We become aware of ourselves as a second human being. We learn to recognize how the etheric forces move in and out, and how everything that is everywhere outside as a universal play of world forces and moves into us is the same as the weaving of thoughts within us in the shadow image. We become aware of how the thoughts within us are the shadow image of the etheric body, how the etheric body is actually a living thing, how it is a link in the whole world ether. We have reached the first stage of supersensible knowledge.

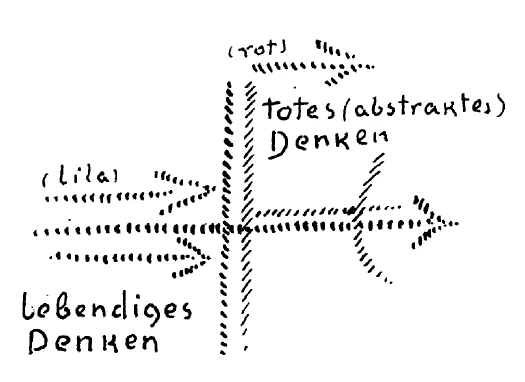

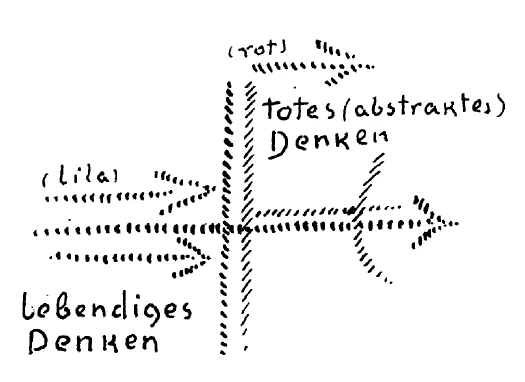

You could say: What comes to light in thinking is actually formed as if through a mirror (see drawing). There is the coating of the mirror. Thus the mirror is directed forwards, towards the senses (red arrow). That which is taken in through the senses is reflected back and comes to consciousness when it reaches the nerve stumps. But there is also an inner activity which does not proceed in this way, but which passes through the mirror (purple arrows). If we follow this, then we have a body of image forces that is part of the image forces of the whole universe. In this way, however, we have come to the other side, so to speak, for thinking.

What is this practicing that leads to imaginative thinking? It consists in the fact that, whereas otherwise one always sees only as far as the mirror of one's inner being, to that which is reflected from within, but which is nothing other than outer nature, one now acquires the ability to see behind the mirror. There is not the same as in outer nature; there are the human-creative powers. This is the other side of thinking. Here is dead thinking, also called abstract thinking. There is living thinking. And in living thinking, thoughts are forces.

This is precisely the secret of thinking, that what one actually has within oneself in ordinary thinking is only the shadow image of what true thinking is. But true thinking pervades the world, is in the world as a power structure, not just in man.

It is not very clever at all for man to believe that thinking is only in him. It's a bit like drawing water from a stream and drinking it and then thinking: Yes, my tongue, it has continually brought forth the water. We draw water from the entire water supply of the earth. Of course, we are not under the illusion that our tongue produces the water. Only when we think do we do that. There we speak of the brain producing thought, while we merely draw from the total thought that is universally spread out in the world, which we then have within us as a sum of thoughts.

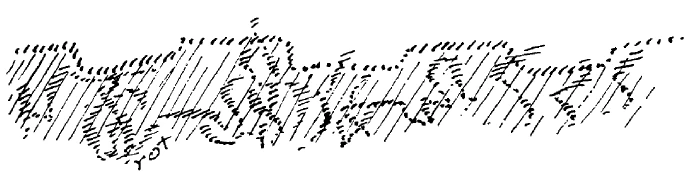

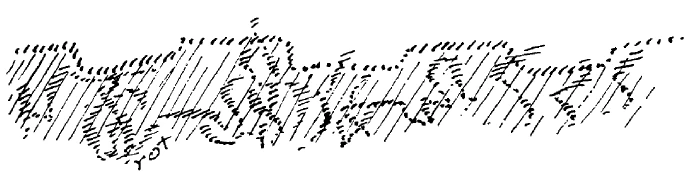

Man indulges in yet another illusion when he thinks of his imagination, an illusion that I can compare with the following. Imagine a path like the one down to Arlesheim and Dornach, such a soft path! I am now walking over it. You will see the tracks of my feet (see drawing, red). Now someone comes from Mars, has never seen anything like it on Earth, sees the tracks. He doesn't know any humans, because he comes from Mars, and it's at a time of day when no one has ever walked before. He sees the tracks. Aha, he thinks, there's the earth, there are the tracks; down there is earth, that's substance - he already knows that from Mars - down there in the earth's substance are all kinds of forces, vibrating forces, or whatever, ions or electrons, whatever it may be. These forces, they play below, and they cause the traces here, and that is why you can see the traces.

But the good inhabitant of Mars is mistaken, he does not notice that I have gone over there and that the earth has done nothing at all, that this earth down to Arlesheim is most innocent of these traces. There are no forces down there that have caused it to be configured, it came from outside.

Man also indulges in these illusions with regard to the brain. Such structures are also there, and he thinks that these structures are caused from within, and that this then appears in the thoughts. But they are traces made from the outside. We really do find a complete imprint of thought in the brain. There is nothing better to do than to follow how a person's thinking is represented down to the smallest detail in the forms of the brain. But just as little as the footprints in the earth have arisen from below, just as little have these formations of the brain arisen from anything other than impressions which the living thinking, which comes from the world ether, which lives and lives in the world ether, has dug into it.

What I am telling you now becomes a living view when one penetrates to this imaginative thinking. And just as you can grasp thinking from the other side, so to speak, you can now grasp another element that you experience somewhat earlier in normal human life, speech, also from behind, so to speak, from the other side.

Imagine that you let the air flow inwards through your lungs, through the larynx and through the other organs of speech. Through the formation of the larynx, the tongue, the palate and so on, the sounds are formed on the outside. If you follow this whole process from a certain point in the organism, you will have outward speech. But imagine that you are not tracing speech outwards from the speech organs, but you are tracing the process backwards (see drawing, red) to speech. Again, you cannot do this with ordinary consciousness, you must achieve this through exercises, that you follow the inner up to the point where the speech of earthly life forms outwards, that you follow the inner up to this point where speech first forms. This is not found in the physical and not in the etheric body, this is now found in an even higher part of the human organism than the etheric body or the body of formative forces, this is found in what I have called the astral body in my books.

What is spoken outwardly is language for earthly life. That which approaches the human being from behind, as it were, that which reaches the organs of speech, that which does not sound outwards as speech, but that which speaks inwards, that which does not emerge from the larynx outwards as earthly audible speech, but that which comes from behind, stops at the larynx, becomes mute there, instead of speech beginning there, which goes out earthly: that is spiritual speech. This is what we can call the spiritual language that is spoken to us from the spiritual world.

The impression that one receives through it, that is the inspiration, now meant in a quite rational sense. This inspiration must be brought about by withdrawing the consciousness, again through the exercises which I have described in the books I have mentioned, from being devoted to the outer words. Again, that which reaches the larynx or the organs of speech was particularly strong, and that which speaks to us from the world, whereas otherwise we speak to the world through our organs of speech - this inspiring was particularly strong in childhood, until we learned to speak. When we learned external language, these forces ceased to work in this way. They are now only present within us, and we attain them when we rise to the gift of inspiration.

Then we become aware of a third element within us, a third person who now does not belong to space and time, but who is strong and formative within us. This is the astral body. It is the astral body in which the processes are inspirations, where we experience what is actually behind our emotional life. The emotional life is the dreaming of that which flows into us in an inspiring way. And this emotional life is intimately connected with the breathing and speaking process.

Therefore, in older times, when people wanted to ascend into the spiritual world in a different way, this breathing process, the inner breathing process, was influenced by exercises. And the old yoga exercises were calculated to direct attention to that which lies behind speech. By putting artificial breathing in the place of natural breathing, one became aware of it, just as one becomes aware of something everywhere when one deviates from the ordinary.

Just think that you perceive the water in a river around you in different ways when you swim with the speed of flowing water, or when you swim slower or faster. If you swim at the speed of flowing water, you do not perceive a certain counter-pressure. If you swim more slowly, you will perceive it. Because the Indian yogi shapes his breathing in a different way than it naturally proceeds, he perceives that which is in the breathing stream as spiritual, that spiritual through which we have our astral body, and through which we in turn project into a higher world than the etheric world.

For us these exercises are the right ones - because humanity is progressing - which I have described in “How do you gain knowledge of the higher worlds?”. But you see, everywhere one can point to the concrete processes that underlie what the outside world finds so fantastic when anthroposophy speaks of man not consisting of the physical body alone, but of the physical body, etheric body, astral body and ego. We will talk about this next time. But these things have not been pulled out of our fingers, these things have not been speculated, but have come about through careful research, which takes the scientific method further right up to the human being, to the whole being of the human being - albeit research that is dependent on the human cognitive faculties being increased more and more.

So what does the imagination consist of, through which one penetrates into the etheric world and into the actual etheric life? This imagination consists in the fact that one not only pursues into the senses the processes that are first pushed backwards through the senses and can then be pushed forward again to the nerve endings, but that one becomes aware of that which is from the universe, from the cosmos, of the same kind as the sensory perceptions, but now belongs to the supersensible world, that one becomes aware of it as otherwise only the memories do.

If one becomes aware of the world-creating forces, as one otherwise perceives the memories, then one has imaginative being, then one experiences the etheric being of the world. If one becomes aware behind the language of that which now does not go out from the larynx to the front, but speaks in from the other side from the universe, from the cosmos, but falls silent at the larynx, then one becomes aware through inspiration of a further world to which we belong with our third human organism, with the astral body.

However, one thing becomes apparent. Here in the physical-sensory world we have on the one hand the physical processes and on the other the moral impulses that rise from within us. They stand side by side in such a way that even today theology would like the sensory world to be understood only sensually, and for the moral world there would be a completely different kind of knowledge. The moment we advance to inspiration, when we live not only in the world in which we speak from the larynx forward, but when we live in the world which speaks through our whole human being, but falls silent at the larynx, because we push the gate forward when we learn the outer language, so that we experience the outer language as a substitute for the heavenly language - the moment we live into this world, when we live into this world, which now ends at the larynx, then we experience the inspirational content of the world, then we experience the secrets of the world, and then we do not merely experience a nature which moral impulses cannot approach, but we experience a world behind the natural existence where natural impulses, natural laws and moral laws are interwoven, where they are one. We have lifted the veil and found a world in which the moral and the physical resonate with each other. And we shall see that this is the world in which we were in the pre-earthly existence before we descended to earth, into which we enter again after we have passed through the gate of death.

II. Das Seelenleben des Menschen und Seine Entwickelung zur Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition

Dornacd, 15. April 1923

Ich habe gestern versucht, über die Wesenheit des Menschen und die Wesenheit des menschlichen Lebens einiges von dem Gesichtspunkte aus zu betrachten, der sich ergibt, wenn man das menschliche Leben in seiner Vollständigkeit vor die Seele hinstellt. Ich sagte, es verfließt dieses menschliche Leben nicht bloß während des Tagwachens, sondern ungefähr ein Drittel des menschlichen Gesamtlebens verfließt im Schlafe. Und wir stehen zunächst, wenn wir nur das gewöhnliche menschliche Bewußtsein ins Auge fassen, so vor diesem Menschenleben, daß, wenn wir erinnerungsgemäß ins Erdendasein zurückblicken, wir eigentlich nur immer die Tage, diejenigen Zeiten unseres Lebens, die wir wachend zubringen, im Gedächtnisse haben. Wir übersehen gewissermaßen immer dasjenige, was in der Zeit verläuft, die wir verschlafen haben. Nun muß ja allerdings gesagt werden: Für das, was wir äußerlich für die Erdenkultur, das Erdenleben zu schaffen haben, kommt unser waches Tagesleben in Betracht; es handelt sich aber darum, ob auch nach dem Innern,des Menschen hinein nur diejenigen Vorstellungen in Betracht kommen, die sichim wachen Tagesleben vor dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein abspielen.

Daß das nicht der Fall ist, kann schon eine oberflächliche Betrachtung lehren. Allein diejenigen Betrachtungen, die ich heute und in den letzten Tagen dieser Woche anstellen will, werden zeigen, daß allerdings die Ereignisse, die die menschliche Seele vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen erlebt, verborgen bleiben, daß diese Ereignisse aber für das Innere des Menschenwesens auf Erden ungleich wichtiger noch sind als die Ereignisse, welche sich während des Tages abspielen.

Heute wollen wir zunächst in Fortsetzung des gestern Ausgeführten einiges betrachten, was sich wiederum aus einem Vergleiche des Schlafeslebens und des gewöhnlichen wachenden Lebens ergibt. Das Schlafesleben verläuft ja zum Teil in vollständigem traumlosen Schlaf. Da ist dann die Zeit, die wir mit unserem Erdenleben während dieses traumlosen Schlafes zubringen, falls sie Ereignisse für unser Leben enthält, ganz unbewußt. Aus dieser Unbewußtheit, aus dieser vollständigen Finsternis des Bewußtseins tauchen dann die Träume herauf, und aus den Träumen wachen wir entweder auf zum gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, indem uns durch die Sinneswahrnehmung und durch die Verstandeskombination die irdische Wirklichkeit gegeben ist, oder auch wir schlafen aus dieser Wirklichkeit durch den Traum in das traumlose Bewußtsein hinein.

Machen wir uns noch einmal klar, worin eigentlich für die gewöhnliche äußere Beobachtung der Unterschied des Träumens von der äußeren Sinnesbeobachtung, die in Bildern und Verstandesbegriffen lebt, besteht.

Wir können sagen: Für viele Menschen enthält der Traum seinem Inhalte nach eine oftmals lebendigere Wirklichkeit, als diejenige ist, die im wachen Tagesleben abläuft. Aber es ist dies eine Bildwirklichkeit, der wir nicht mit unserem Willen, sondern zwangsmäßig mit der Seele folgen. Und wir können den Unterschied zwischen dem Verfolgen dieser Traumesbilder und dem Verfolgen der gewöhnlichen Wirklichkeitsbilder des wachen Tageslebens ganz genau angeben. Auf besondere philosophische Spekulationen wollen wir uns dabei nicht einlassen. Die könnten auch angestellt werden, wir wollen sie aber jetzt unterlassen. Wir wollen nur auf das hinschauen, was das ganz populäre Bewußtsein gibt. Da können wir sagen: Die Traumesbilder sind so, daß wir in ihnen leben. Wir leben in den Bildern selbst. Wir leben mit den Bildern. Beim wachen Tagesleben haben wir natürlich Farbenbilder, Tonbilder und so weiter in derselben Art vor uns wie im träumenden Erleben. Aber wir sind genötigt, diese Bilder, seien sie Gesichtsbilder, seien sie Tonbilder, Wärmebilder, Tastbilder und so weiter, gewissermaßen auf die harte Wirklichkeit zu beziehen. Wir sehen in der Tageswirklichkeit überall die Notwendigkeit, gewissermaßen auch mit unserem Willen auf das zu stoßen, was uns das Bild zeigt.

Das ist nicht der Fall bei der, nun, sagen wir Traumeswirklichkeit. Die Traumeswirklichkeit ist gewissermaßen, wenn ich mich grob ausdrücken darf, überall zu durchstoßen. Wir können den Gesichtspunkt, von dem aus wir die Wirklichkeitsbedeutung des Traumes beurteilen, nur innerhalb des wachen Tageslebens finden. Solange wir träumen, halten wir den Traum für Wirklichkeit, und wenn wir unser ganzes Leben träumen würden, so würde die Traumeswirklichkeit die einzige Wirklichkeit für uns sein. Wir brauchen uns gar nicht vorzustellen, daß dann das äußere Leben anders verliefe, als es jetzt verläuft. Wir könnten uns ja vorstellen, die einzelnen Menschen begegneten sich im Leben nicht durch ihren Willen, sondern durch Naturkräfte wie automatisch zueinander geschoben oder auch durch irgendwelche höheren Wesen zueinander geschoben. Wir könnten uns auch vorstellen, die Menschen würden an ihre Arbeit getrieben, von höheren Wesen oder von Naturkräften geschoben. Kurz, alles, was wir so im wachen Tagesleben vor uns haben, könnte geschehen. Wir brauchten nichts davon zu wissen. Wenn wir nur träumten, würden wir eine Traumeswirklichkeit vor uns haben. Wir würden gar nicht darauf kommen, irgendwie durch diese Wirklichkeit durchstoßen zu wollen auf eine andere Wirklichkeit. Wir wachen durch die naturgemäße Organisation unseres Organismus auf und gewinnen dann innerhalb der Sinneswirklichkeit den Gesichtspunkt, um den anderen relativen Wirklichkeitswert des Traumes zu beurteilen.

Also erst wenn wir diesen Lebensruck durchmachen vom Träumen zum Wachen, gewinnen wir den Gesichtspunkt, um den relativen Wirklichkeitswert des Traumes zu beurteilen.

Wir müssen uns nun aber fragen: Ist alles das, was wir während des Tagwachens erleben, wirklich wacher Zustand? Nun, ich habe gestern im einzelnen ausgeführt, daß das nicht der Fall ist. Ich habe im einzelnen ausgeführt, daß eigentlich nur unsere Vorstellungen, aber diese auch nur insofern sie die äußere Wirklichkeit abbilden, uns ins Wachen versetzen. So daß wir eigentlich nur in unseren Vorstellungen wachen. In unseren Gefühlen haben wir keine andere Wirklichkeit in bezug auf die Seelenverfassung vor uns als im Traume; nur daß der Traum uns in Bildern erscheint, die Gefühle in jener Unbestimmtheit, mit der sie eben aus den Tiefen des Seelenlebens heraufkommen.

Ist man aber nicht ein gewöhnlicher Psychologe, der alles nach irgendwelchen Vorurteilen zurechtschmiedet, sondern geht man unbefangen beobachtend auf den Gefühlsinhalt der Seele, so sieht man, wie die Gefühle, die ja allerdings gegen das Vorstellungsleben, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, heraufschießen, eine Verschwommenheit, ein fluktuierendes Ineinanderübergehen zeigen wie die Traumbilder. Fühlend träumen wir auch, wenn wir wachen. Nur weil, ich möchte sagen, die Substanz, in der die Traumbilder erscheinen, anders ist als die Substanz der Gefühle, kommen wir nicht darauf, daß eigentlich alles Fühlen nur die Wirklichkeitsbedeutung hat, die der Traum auch hat. So daß, während wir wirklich wachend vorstellen, unsere Vorstellungen fortwährend durchflutet werden von den unbestimmten subjektiven Gefühlsinhalten.

Stellen Sie sich lebhaft vor, wie beim Aufwachen hereinspielen die Traumbilder in das wache Tagesbewußtsein, wie in den Traumbildern alles fluktuierend vergrößert, verkleinert ist — je nachdem -, so werden Sie sich sagen können: Da kommt, scheinbar natürlich, in Bildern etwas an den Menschen heran, was sonst im Gefühlsleben wiederum verschwommen, die Dinge subjektiv vergrößernd, verkleinernd, von innen heraus an den Menschen herankommt.

Und mit Bezug auf unser Wollen sind wir auch im Wachen im tiefen Schlaf. Wir wissen ja vom Wollen nur die Absichten. Das sind aber Gedanken, Vorstellungen. Wenn ich einen Spaziergang machen will, habe ich zunächst die Vorstellung, diesen Spaziergang zu machen. Dies ist meine Absicht. Wie nun diese Absicht stetig in meinen Organismus hineingeht, das zeigt ja das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein ebensowenig, wie es das zeigt, was vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen verfließt. Den Erfolg kann ich wiederum erst an der Bewegung ermessen, die ich mache, an der Veränderung der Aspekte, die vor mir auftreten, wenn ich den Spaziergang mache - also wiederum an Vorstellungen. Was zwischen der Vorstellung der Absicht und der Vorstellung des Erfolges eigentlich im Organismus vor sich geht, das verschlafe ich für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein ebenso, wie ich das verschlafe, was sich abspielt vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen.

So können wir sagen, daß der Mensch wollend, auch wenn er wacht, im tiefen traumlosen Schlaf ist, daß er fühlend träumend ist, auch wenn er wacht, und daß er nur in einer gewissen Weise wach ist, wenn er in Vorstellungen lebt. Aber wenn der Mensch wirklich ehrlich nach seinem Innern hinschaut, so merkt er: diese Vorstellungen sind auch nur wach in bezug auf die äußere Natur, nicht in bezug auf ihr eigenes Leben. In bezug auf das eigene Leben der Vorstellung kann der Mensch nicht zu einem rechten Wachen kommen. Man muß sich nur klar sein darüber, wie ja für die meisten Menschen, wenn sie nichts Außerliches vorstellen können, eine vorstellende Tätigkeit überhaupt nicht mehr vorhanden ist. Aber das ist ja eigentlich nur deshalb, weil insbesondere in der heutigen Kultur der Mensch an die Außenwelt hingegeben ist, so daß wir dieses Hingegebensein vergleichen können mit dem Dasein in einer tosenden, brausenden Welt.

Denken Sie sich einmal, hier spiele jemand Piano oder irgendein Instrument, und da draußen tosten die Maschinen in einer ganz außerordentlichen Weise. Sie würden die Maschinen hören. Das Piano würden Sie wenig wahrnehmen können, besonders wenn Sie etwas weiter weg davon wären. So ist es im Grunde genommen auch gegenüber dem, was eigentlich im Innern des Menschen von der Denktätigkeit lebt. Nur müssen wir da den Vergleich richtig gebrauchen. Wenn wir heute die äußere Naturwissenschaft lernen, wenn wir da alle die Begriffe aufnehmen, die in der äußeren Evolutionslehre dem Menschen gebracht werden, dann ist das im Grunde genommen ein Denkgetöse, ein Denklärm. Und dieser Denklärm, dem sich der heutige Mensch, insbesondere auch wenn er Wissenschafter ist, hingibt, stört ihm die feinere Wahrnehmung der inneren Denktätigkeit. Daher verschläft er auch die innere Denktätigkeit.

Ich habe in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» auf dieses reine Denken, das nicht etwas Äußerliches denkt, sondern das ganz im Innern des Menschen verläuft, hingewiesen. Aber ich bin mir auch bewußt, daß ich mit diesem reinen Denken eigentlich etwas geschildert habe, von dem viele unserer Zeitgenossen sagen, das gibt es ja gar nicht; so wie derjenige, der das Getöse von Maschinen da draußen hören würde und das Piano nicht, sagen würde, das gibt es ja gar nicht.

Aber wenn das so ist, können wir etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges daraus ersehen, nämlich dieses, daß wir eigentlich nur für das Denken, insofern es einen äußeren Naturinhalt hat, wachen, daß wir aber in bezug auf die innere Tätigkeit, die wir da vollbringen, schon höchstens träumen. Außerdem träumen wir die Gefühle und verschlafen den Willen. Also die Seelentätigkeit, dasjenige, was uns im Innern lebt, das ist im Grunde genommen nicht erwacht, wenn wir für die Sinneswelt wachen. Wir schlafen fort, auch während des Tagwachens, für unsere Denktätigkeit, für das Fühlen, für das Wollen. Wir wachen nur für die äußere Natur auf. Und dieses Aufwachen, das bilden wir ja noch durch Instrumente, durch Experimentiermethoden aus und gelangen dadurch gerade zu der bedeutungsvollen Naturwissenschaft der Gegenwart. Die muß entstehen, indem sich die äußeren Vorgänge gewissermaßen in den Vorstellungen spiegeln. Aber wir wachen nicht in demselben Maße für unser Denken, Fühlen und Wollen auf. Und wer unbefangen betrachten kann, wie sich eigentlich der Traum von der äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Wahrnehmungswelt unterscheidet, der wird das Seelenleben nach Denken, Fühlen und Wollen nichtähnlich finden demjenigen, was äußere sinnliche Wahrnehmungseindrücke sind, sondern er wird dieses Seelenleben höchstens ähnlich finden seinem bedeutsamsten Elemente, dem Träumen. Mit Bezug auf unseren Seeleninhalt träumen und schlafen wir eigentlich fortwährend. Wir wachen nur zum Naturinhalte auf. Wir wachen gar nicht zu unserem Seeleninhalt auf im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, da schlafen wir sanft fort. Und wir sagten ja: Die Traumesbilder sind gewissermaßen so, daß man sie durchstoßen kann, daß sie nicht auf einer harten äußeren Wirklichkeit aufliegen, die dem Willen unterliegt. So ist aber unser Seeleninhalt auch. Er lebt in Bildern. Und wer die Fähigkeit hat, Qualitäten zu vergleichen, nicht bloß Quantitäten, der wird schon finden, daß, wenn er dem Trauminhalt Bildcharakter beilegt, der zunächst nicht auf eine Wirklichkeit weist, er dem eigenen Seeleninhalt auch Bildcharakter beilegen muß.

Dann aber entsteht daraus gerade eine bedeutungsvolle Frage. Lebe ich in Träumen, so wache ich zu der physischen Wirklichkeit auf, fühle mich dann dadurch, daß ich mit meinem Willen in meinen Leib eingeschaltet bin, mit der physischen Wirklichkeit als mit einer Realität verbunden, und ich spreche vom Gesichtspunkte dieser physischen Wirklichkeit aus dem Traum höchstens eine relative, eine ganz andersartige Realität zu.

Kann ich nun - so ist die Frage - in derselben Weise für das Seelenleben aufwachen, wie ich für die Natur aufwache? Kann ich mich einschalten, wie ich durch meinen Willen, den ich in meinen Leib hineinrücke, die Traumesbilder einschalte in das, was die Struktur der Wirklichkeit ist, kann ich ebenso das Denken, Fühlen und Wollen durch ein höheres Erwachen einschalten in eine entsprechende Wirklichkeit? Das, sehen Sie, ist die Frage: Kann ich für das Seelenleben ebenso aufwachen, wie ich für die Natur aufwache? Der Naturinhalt, den ich als Mensch während des Erdendaseins mit der äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Wirklichkeit erlebe, erscheint mir bildhaft im’ Traume. Aber das ganze Seelenleben erscheint mir auch nur bildhaft wie im Traume. Also, kann ich für das Seelenleben aufwachen?

Ja, man kann aufwachen. Man kann dadurch aufwachen, daß man sich eben durch solche Übungen, wie ich sie angegeben habe in dem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» und in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft», zunächst das Denken verschärft, verinnerlicht, daß man nicht bloß sich anregen läßt zu einem Gedankeninhalt von . außen, sondern daß man sich einen überschaubaren Gedankeninhalt, der einem nicht suggeriert wird, von innen gibt, dann auf diesem Gedankeninhalt ruht, sich konzentriert auf einen solchen aktiv von innen der Seele gegebenen Gedankeninhalt. Dann kommt man auf diese Weise nach und nach zum wirklichen Bewußtsein des Denkens.

Man hat ja gar nicht das Bewußtsein des Denkens, wenn man sich für die Vorstellungen nur von außen anregen läßt. Nur wenn man immer wieder und wiederum sich von innen zum Denken anregt durch Meditation, durch Konzentration auf Gedankeninhalte, dann wird man sich gewahr innerhalb des Denkens. Dann geht einem auf, daß man eigentlich in diesem Denken lebt, aber daß man es nur nicht weiß, wenn man sich allein von außen anregen läßt. Das Denken wird auf diese Weise lebendig, während es sonst abstrakt und tot ist. Das Denken wird etwas, was nicht bloß in den Denkschatten besteht, die wir von außen bekommen, sondern etwas, was sich wie ein Seelenblut innerlich regt. Man wird wie ausgefüllt mit einer zweiten Menschlichkeit.

Die Gedanken werden lebendige Kräfte, Bildekräfte, wie ich sie auch in meinem Buche «Theosophie» genannt habe. Und man wird gewahr, daß man das Denken eigentlich als einen zweiten Leib in sich trägt, als den Ätherleib, als den Bildekräfteleib; denn man wird gewahr, daß dasjenige, was sonst nur abgeschattet in Gedanken besteht, eigentlich dieselben Kräfte sind, die unser Wachstum bewirken. Man zieht sich zurück in das Wachstum seines menschlichen Wesens, und man kommt darauf, wie das, was als die Prozesse, die sonst bloß chemisch verlaufen würden nach Maßgabe der Eigentümlichkeiten der Stoffe, die wir aufnehmen, wie das durch dieselbe innere Geistleiblichkeit, ätherische Leiblichkeit, die unsere Gedanken bildet, verarbeitet wird, wie wir ein einheitlicher innerer Mensch werden durch diese innerlich lebendigen, sich regenden Gedanken. Man lernt also in sich einen zweiten Menschen auf diese Weise kennen.

Aber man kommt noch auf etwas anderes. Dieser zweite Mensch, den man da kennenlernt, der ist nicht etwa bloß eine Wolke, die den räumlichen physischen Leib unbestimmt ausfüllt. Dieser zweite Mensch ist eigentlich in fortwährender Bewegung, und es ist gar nicht möglich, ihn in einem Momente festzuhalten. Sehen Sie, da ist es eigentlich so: Wenn wir den physischen Leib des Menschen in einem bestimmten Punkte des Lebens haben, dann können wir das, was wir so erleben, und was mit unserem Denken identisch ist — nur daß wir im gewöhnlichen Denken die Schatten der Gedanken haben, nicht die lebendigen Gedanken selbst — für einen Moment da hinzeichnen (siehe Zeichnung). Was als ein solcher zweiter Äther- oder Bildekräfteleib den Menschen durchzieht, ist eben nur für einen Augenblick festzuhalten. Im vorigen Augenblick war das ganz anders; im nächsten Augenblick wird es wieder anders sein, und so weiter zurück und weiter vorwärts.

Dadurch aber ergibt sich, wenn man im inneren, anschauenden Erleben darauf kommt, daß dieser Bildekräfteleib, der sich für das gewöhnlicheBewußstsein alsdie schattenhaften abstrakten Gedanken durchdrückt, überhaupt nichts Räumliches ist, daß er etwas ist, was in der Zeit verläuft. Das führt uns zurück als ein lebendiges Tableau bis zu einem gewissen Momente unserer ersten Kindheit. Ich will jetzt das schematisch zeichnen. \

Stellen wir uns vor, wir seien schon ein älterer Mensch in dieser Zeit; aber dieser Bildekräfteleib ist nicht auf eine Zeit beschränkt, sondern führt zurück bis in unsere Kindheit. Wir überschauen unser Leben nicht erinnerungsgemäß, sondern wie ein Tableau auf einmal. Was ich hier räumlich zeichne, ist zeitlich. Das führt jetzt zurück bis in unsere Kindheit, bis zu dem Zeitpunkt in unserer Kindheit, bis zu dem wir uns in der Regel erinnern.

Da ist jetzt auch dieser Ätherleib, dieser Bildekräfteleib. Aber wenn man durch sorgfältige Übungen die Fähigkeit erwirbt, bis dahin zurückzuschauen, dann kommt man bis zu dem Zeitpunkt, wo man als kleines Kind denken gelernt hat. Da ist es so, wie wenn man mit dem Denken, zunächst mit dem gewöhnlichen Denken, an eine Grenze käme. Für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein, für die gewöhnliche Erinnerung kommt man an diese Grenze. In der Imagination kommt man weiter zurück an die andere Seite. Man schaut in denjenigen Seeleninhalt des Kindes hinein, den man gehabt hat, als man noch nicht hat denken können, als man als Kind sich hereingeträumt hat in die Welt. Denn in einem bestimmten Momente ist ja erst das Denken, und zwar nach dem Sprechen, aufgetreten.

Nun sieht man dadurch in die Zeit hinein, sieht, wie es war in der Seele, bevor man die schattenhaften abstrakten Gedanken gehabt hat. Da hat man eben noch das lebendige Denken gehabt. Und das lebendige Denken hat wuchtig plastizierend gearbeitet an dem menschlichen Gehirn, an der ganzen menschlichen Organisation. Später, wenn vieles von diesem Denken in die Abstraktheit hineingenommen wird, in das Tote hinein, da sind auch nur noch Reste für die Bearbeitung der menschlichen physischen Organisation da. Während man als Kind träumt, noch nicht denken kann, da ist das Denken regsam. Eben weil man im späteren Leben durch das Getöse der Welt nicht auf solches Denken hinschauen kann, kommt es auch gar nicht vor, daß man da in das Denken, das noch regsam tätig war, zurückblickt. Jetzt kann man zurückschauen. Und dann erscheint dieses Denken als die Summe der Kräfte, die einen eigentlich menschlich aufgebaut hat, als Wachstumskräfte, als Ernährungskräfte und so weiter. Man merkt, wie aus dem Ather der Welt, denn darinnen liegen diese Kräfte, die menschliche Organisation herausgebaut wird. Man kommt an den Ätherleib immer mehr und mehr heran. Man weiß, wie dieser Atherleib am tätigsten ist von außen herein in das Kind in den allerersten Jahren, wenn das Kind noch nicht denken kann, wenn es das Leben noch träumend verbringt. So rückt man zur Imagination vor.

Aber etwas kann einem bleiben. Man merkt es nicht, wenn man eben nicht unserer heutigen, in ihrer Wissenschaftlichkeit tosenden Kultur gegenüber Übungen macht, wie ich sie in den genannten Büchern angegeben habe. Dann aber kommt man darauf, daß einem etwas geblieben ist von diesem Denken von der anderen Seite her, wie man es als kleines Kind gehabt hat. Dieses Denken, das aufbauend, bildend ist für den Organismus, dem man seinen äußeren physischen Organismus erst verdankt, dieses regsame Denken habe ich in meinen Büchern das imaginative Denken genannt. Aber es bleibt einem eben etwas von diesem imaginativen Denken, und durch Übung kann man es auch im späteren Leben wieder erforschen, so daß man an den Ätherleib heran kann.

Ich habe schon gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, aber da nicht alle da waren, möchte ich noch einmal darauf hinweisen: Nehmen Sie das menschliche Auge, von dem menschlichen Auge den Sehnerv, der nach innen geht, sich im Auge ausbreitet. Wenn Sie mit dem Bildekräfteleib (lilarot), der im wesentlichen den äußeren physischen Nervenvorgängen (gelb) folgt, so weit gehen, daß Sie herankommen an diejenigen Vorgänge (rot), wo sich durch das Auge die Außenwelt spiegelt, dann haben Sie Wahrnehmung der äußeren Welt. Und was dann im Nerv sich festlegt — ich will jetzt nur dieses approximativ bezeichnen, es würde zuviel Zeit in Anspruch nehmen, wenn ich den genauen Vorgang schildern würde — das, was sich durch den Nerv festlegt im Bildekräfteleib, das kann dann immer wiederum zur Tätigkeit angeregt werden. Da kommt man mit der Tätigkeit des Bildekräfteleibes, des Nervensystems, bis dahin, wo die Nerven endigen (gelb). Man durchstößt gewissermaßen nicht den Nerv bis hinein zu den Vorgängen, die die äußere Welt spiegeln, man gibt nur dem, was in ihnen lebt im Bildekräfteleib, einen Anstoß, stößt diesen Bildekräfteleib bis dahin, wo die Nervenstumpfe auslaufen, dann bekommt man den Erinnerungseindruck. Der Erinnerungseindruck besteht im wesentlichen darin, daß man mit der inneren Tätigkeit bloß bis zu den Nervenendigungen kommt; während man für die Sinneseindrücke die Nervenendigungen durchstößt und bis an die hauptsächlich durch das Blut bewirkten Vorgänge in den Sinnen vorrückt.

Da sehen Sie die lebendige Tätigkeit des Bildekräfteleibes. Aber alles das, was Sie da in die Erinnerung hineinschieben, das muß ja ins Nervensystem hineingegangen sein, also rührt es her erst seit jener Zeit, seit wir denken gelernt haben als ganz kleines Kind. Was vorher war, das ist nun so-und wenn man jetzt durch Übungen das Denken geschult hat und zurückblickt, so sieht man dieses im Rückblick durch den zeitlich verlaufenden zweiten Menschen -: Da wird man gewahr, wie auf denselben Wegen, auf denen sonst die außen hineingehenden Eindrücke wiederum umkehren durch das Gedächtnis im Erinnerungsvermögen, wie da gewissermaßen von hinten hereinkommt dasjenige, was nun auch Tätigkeit des Bildekräfteleibes ist. Fortwährend hat man eigentlich diese zwei Tätigkeiten. Nur weiß der Mensch im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nur von der einen, von der Erinnerung. Man hat aber diese zwei Tätigkeiten: Das, was herrührt von den äußeren Sinneswahrnehmungen, die zurückgeschoben werden, wiederum bis an die Nervenstumpfe vorgeschoben werden können, so daß eben die Erinnerungsbilder auftauchen; man hat aber auch etwas, was gewissermaßen menschenschöpferisch von derjenigen Seite her in das ganze Nervensystem sich ergießt, wo man eben nicht in derselben Stärke wie an der Vorderseite des Körpers sinnlich wahrnimmt.

Von rückwärts — es ist das natürlich nicht ganz genau gesprochen — kommen die schöpferischen Kräfte in den Menschen herein: In der ersten Kindheit, wo man noch nicht denken kann, ganz mächtig, später schwächer. Das ist das Denken, das nicht aus der Sinneswelt, das aus dem gesamten Weltall genommen ist, das aus dem Weltenäther genommen ist, das wir uns aneignen, indem wir vom vorirdischen Dasein in das irdische heruntersteigen, das wir noch übermenschlich behalten bis zu dem Momente, wo wir denken lernen. In dem Momente, wo wir denken lernen, machen wir gewissermaßen nach dem fortlaufenden Strom unseres Lebens hin das Tor zu für dieses regsame Denken, für diese Entwickelung der menschlichen Bildekräfte im Bildekräfteleib, im Ätherleib. Für die äußere Sinneswelt denken lernen heißt: das Tor für die universellen weltenbildenden Gedankenkräfte zumachen.

Wir haben also, als wir in der Kindheit waren, das Tor für die weltenbildenden Gedankenkräfte zugemacht. Sie bleiben aber in uns, denn wir brauchen diese Bildekräfte in der ersten Zeit unseres Lebens fortwährend, solange wir wachsen als Wachstumskräfte, später als die Verarbeitungskräfte für das, was wir als Ernährung und so weiter in uns aufnehmen. Aber wir bemerken sie nicht. Wir bemerken nur dasjenige, was der Bildekräfteleib spiegelt aus den aufgenommenen Eindrücken, die dann in den Erinnerungen bis an die Nervenendigungen stoßen.

Aber wir können durch Übungen der Konzentration und Meditation dasjenige gewahr werden, was uns nun selbst aus dem Weltenätherischen herein bildet. Da werden wir in unserer Selbstwahrnehmung Vorgänge gewahr, welche auch in der Zeit verlaufen, die wir nicht aufgenommen haben durch äußere Eindrücke, sondern die nur den Strom nach der einen Seite haben. Wenn wir diese dann verfolgen bis zu dem Punkt, wo die Nerven auslaufen, wo wir sonst die Erinnerungen von äußeren Eindrücken haben, dann bekommen wir nicht nur das Bild unseres Ätherleibes, sondern das Bild davon, wie wir als Mensch im ganzen Weltenäther drinnen enthalten sind. Wir werden uns als zweiter Mensch gewahr. Wir lernen erkennen, wie die Ätherkräfte aus- und einziehen, und wie alles, was da als universelles Spiel der Weltenkräfte überall draußen ist und in uns hineinzieht, wie das dasselbe ist, was im Schattenbild das Weben der Gedanken in uns ist. Wir werden gewahr, wie die Gedanken in uns das Schattenbild des Ätherleibes sind, wie der Atherleib eigentlich ein Lebendiges ist, wie er ein Glied im ganzen Weltenäther ist. Wir haben die erste Stufe der übersinnlichen Erkenntnis erstiegen.

Man könnte sagen: Was im Denken zum Vorschein kommt, ist eigentlich wie durch einen Spiegel gebildet (siehe Zeichnung). Da ist der Belag des Spiegels. So ist der Spiegel nach vorn, nach den Sinnen gerichtet (roter Pfeil). Das, was durch die Sinne aufgenommen wird, wird zurückgeworfen, kommt zum Bewußtsein, wenn es eben an die Nervenstumpfe kommt. Aber es gibt eben auch eine innere Tätigkeit, welche nicht so verläuft, sondern welche durch den Spiegel durchgeht (lila Pfeile). Verfolgen wir diese, dann haben wir einen Bildekräfteleib, der ein Teil der Bildekräfte des ganzen Universums ist. Dadurch aber sind wir gewissermaßen für das Denken an die andere Seite gekommen.

Was ist denn eigentlich dieses Üben, damit man zum imaginativen Denken kommt? Es besteht darin, daß, während man sonst immer bloß bis zum Spiegel seines Innern sieht, zu dem, was innen herausgespiegelt ist, was aber nichts anderes ist als die äußere Natur, man sich jetzt die Fähigkeit erwirbt, hinter den Spiegel zu sehen. Da ist nicht dasselbe, wie in der äußeren Natur; da sind die menschenschöpferischen Kräfte. Das ist die andere Seite des Denkens. Hier ist das tote Denken, auch abstraktes Denken genannt. Da ist das lebendige Denken. Und im lebendigen Denken sind die Gedanken Kräfte.

Das ist eben das Geheimnis bezüglich des Denkens, daß dasjenige, was man im gewöhnlichen Denken eigentlich in sich hat, nur das Schattenbild dessen ist, was das wahre Denken ist. Aber das wahre Denken durchzieht die Welt, ist als Kräftestruktur in der Welt, nicht bloß im Menschen.

Es ist gar nicht sehr gescheit, wenn der Mensch glaubt, das Denken sei nur in ihm. Das ist ungefähr so, wie wenn er Wasser aus einem Bache schöpft und das trinkt und nun die Meinung hat: Ja, meine Zunge, die hat fortwährend das Wasser hervorgebracht. Wir schöpfen das Wasser aus dem gesamten Wasservorrat der Erde. Wir geben uns dabei natürlich nicht der Illusion hin, daß unsere Zunge das Wasser hervorbringe. Nur beim Denken tun wir das. Da reden wir davon, daß das Gehirn das Denken hervorbringt, während wir bloß aus dem Gesamtdenken, das in der Welt universal ausgebreitet ist, schöpfen, was wir dann in uns als Gedankensumme haben.

Der Mensch gibt sich ja noch einer anderen Illusion hin, wenn er an sein Vorstellen denkt, einer Illusion, die ich mit folgendem vergleichen kann. Denken Sie sich einmal, hier wäre ein Weg, wie jetzt ungefähr der nach Arlesheim und Dornach hinunter, so ein weicher Weg! Da gehe ich nun drüber. Sie sehen dann dieSpuren meiner Füße (siehe Zeichnung, rot). Jetzt kommt einer vom Mars, hat niemals so etwas auf der Erde gesehen, sieht da die Spuren. Menschen kennt er nicht, denn er kommt eben vom Mars, und es ist zu einer Tageszeit, wo noch keiner gegangen ist. Da sieht er die Spuren. Aha, denkt er, da ist die Erde, da sind die Spuren; da unten ist Erde, das da ist Substanz — das weiß er schon vom Mars her -, da unten in der Erdensubstanz sind allerlei Kräfte, schwingende Kräfte, oder was immer, meinetwillen Ionen oder Elektronen, was es halt sein kann. Diese Kräfte, die spielen unten, und die bewirken hier die Spuren, und deshalb sieht man die Spuren.

Der gute Marsbewohner irrt sich aber, er beachtet nicht, daß ich da drüber gegangen bin und die Erde gar nichts getan hat, diese Erde bis hinunter nach Arlesheim höchst unschuldig ist an diesen Spuren. Da unten sind keine Kräfte, die das bewirkt haben, daß sie konfiguriert worden ist, sondern das kam von außen.

Der Mensch gibt sich auch diesen Illusionen hin in bezug auf das Gehirn. Es sind auch solche Strukturen da, und er meint, daß von innen heraus diese Strukturen bewirkt werden, und daß das dann in den Gedanken erscheine. Aber es sind die von außen gemachten Spuren. Wir finden wirklich in dem Gehirn einen vollständigen Abdruck des Denkens. Man kann gar nichts Besseres tun als zu verfolgen, wie das Denken eines Menschen bis ins kleinste hinein in den Formen des Gehirnes abgebildet ist. Aber ebensowenig, wie die Fußspuren in der Erde da von unten herauf entstanden sind, ebensowenig sind diese Formationen des Gehirns von etwas anderem als von Eindrücken entstanden, die das lebendige Denken, das aus dem Weltenäther stammt, das im Weltenäther west und lebt, hineingegraben hat.

Das, was ich Ihnen jetzt sage, wird eben lebendige Anschauung, wenn man zu diesem imaginativen Denken vordringt. Und ebenso, wie man das Denken gewissermaßen von der anderen Seite erfassen kann, so kann man jetzt ein anderes Element, das man im normalen Menschenleben etwas früher erlebt, das Sprechen, auch gewissermaßen von hinten, von der anderen Seite erfassen.

Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie lassen die Luft durch Ihre Lunge, durch den Kehlkopf und durch die anderen Sprachorgane nach innen strömen. Durch die Formation des Kehlkopfes, durch die Formation der Zunge, des Gaumens und so weiter bilden sich nach außen die Laute. Wenn Sie diesen ganzen Vorgang von einem bestimmten Punkte des Organismus an verfolgen, so haben Sie nach außen gehend das Sprechen. Aber denken Sie sich, Sie verfolgen das Sprechen nicht von den Sprachorganen nach außen, sondern Sie verfolgen die Sache rückwärts (siehe Zeichnung, rot) bis zum Sprechen hin. Das kann man wieder nicht mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, das muß man durch Übungen erreichen, daß man bis zu dem Punkt, wo das Sprechen des irdischen Lebens nach außen hin sich bildet, daß man bis zu diesem Punkte hin, wo die Sprache sich erst bildet, das Innere verfolgt. Das findet man nicht im physischen und nicht im ätherischen Leib, das findet man nun in einem noch höheren Gliede des menschlichen Organismus, als der Ätherleib oder der Bildekräfteleib ist, das findet man in dem, was ich in meinen Büchern den astralischen Leib genannt habe.

Was nach außen gesprochen wird, ist Sprache für das Erdenleben. Was gewissermaßen von hinten an den Menschen herankommt, was bis zu den Sprachorganen kommt, was nicht als Sprache nach außen tönt, sondern was da hereinspricht, das also, was nicht vom Kehlkopf nach außen als irdisch hörbare Sprache entsteht, sondern was von hinten kommt, am Kehlkopf aufhört, da stumm wird, statt daß da die Sprache beginnt, die eben irdisch hinausgeht: das ist eine geistige Sprache. Das ist etwas, was man die geistige Sprache nennen kann, die zu uns aus der geistigen Welt gesprochen wird.

Die Beeindruckung, die man dadurch erhält, das ist die Inspiration, in ganz rationellem Sinne jetzt gemeint. Diese Inspiration muß man dadurch herbeiführen, daß man das Bewußtsein, wiederum durch die Übungen, die ich in den genannten Büchern geschildert habe, abzieht von dem Hingegebensein an die äußeren Worte. Besonders stark war wiederum das, was da bis an den Kehlkopf beziehungsweise die Sprachorgane herandringt, und was aus der Welt zu uns spricht, während wir sonst durch unsere Sprachorgane zur Welt sprechen — besonders stark war dieses Inspirierende in der Kindheit, bis wir sprechen gelernt haben. Indem wir die äußere Sprache gelernt haben, haben diese Kräfte aufgehört, so zu wirken. Die sind jetzt nur noch in uns vorhanden, und wir erlangen sie, wenn wir uns zu der Gabe der Inspiration aufschwingen.

Dann werden wir ein drittes Element in uns gewahr, einen dritten Menschen, der nun nicht dem Raum und der Zeit angehört, der aber in uns kräftig und bildend ist. Das ist der astralische Leib. Das ist der astralische Leib, in dem die Vorgänge Inspirationen sind, wo wir erfahren, was eigentlich in Wirklichkeit hinter unserem Gefühlsleben sitzt. Das Gefühlsleben ist das Träumen von dem, was da inspirierend in uns einfließt. Und dieses Gefühlsleben hängt innig zusammen mit dem Atmungs- und Sprechprozeß.

Daher hat man in älteren Zeiten, wo man auf andere Weise in die geistige Welt hinaufwollte, auf diesen Atmungsprozeß, den innerlichen Atmungsprozeß eingewirkt durch Übungen. Und die alten Yoga-Übungen waren darauf berechnet, eben die Aufmerksamkeit hinzulenken auf das, was hinter der Sprache sitzt. Dadurch, daß man ein künstliches Atmen an die Stelle des natürlichen setzte, wurde man das gewahr, wie man überall etwas gewahr wird, wenn man vom Gewöhnlichen abweicht.

Denken Sie nur einmal, daß Sie in verschiedener Weise das Wasser in einem Flusse um sich herum wahrnehmen, wenn Sie mit der Schnelligkeit des fließenden Wassers schwimmen, oder wenn Sie langsamer oder schneller schwimmen. Wenn Sie mit der Schnelligkeit des fließenden Wassers schwimmen, so nehmen Sie einen gewissen Gegendruck nicht wahr. Wenn Sie langsamer schwimmen, nehmen Sie ihn wahr. Dadurch, daß der indische Yogi das Atmen in einer anderen Weise gestaltet, als es natürlich verläuft, dadurch nimmt er dasjenige wahr, was da im Atmungsstrom als Geistiges darinnen ist, jenes Geistige, wodurch wir unseren astralischen Leib haben, und wodurch wir wiederum in eine höhere Welt, als die Ätherwelt ist, hineinragen.

Für uns sind diese Übungen die richtigen — denn die Menschheit schreitet vorwärts —, die ich in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» geschildert habe. Aber Sie sehen, überall kann man hinweisen auf die konkreten Vorgänge, welche dem zugrunde liegen, was die Außenwelt so phantastisch findet, wenn in der Anthroposophie davon gesprochen wird, der Mensch bestehe nicht aus dem physischen Leib allein, sondern aus physischem Leib, ätherischem Leib, astralischem Leib und Ich. Wir werden davon dann das nächstemal reden. Aber diese Dinge sind nicht aus den Fingern gesogen, diese Dinge sind auch nicht erspekuliert, sondern durch ein sorgfältiges Forschen, das gerade die naturwissenschaftliche Methode weiterführt bis an den Menschen heran, bis an das Gesamtwesen des Menschen, zustande gekommen - allerdings ein Forschen, das davon abhängig ist, daß man die menschlichen Erkenntnisfähigkeiten immer mehr und mehr erhöht.

Worin besteht also die Imagination, durch die man in die Ätherwelt und in das eigentliche Atherleben eindringt? Diese Imagination besteht darin, daß man nicht nur bis in die Sinne hineinverfolgt die Vorgänge, die durch die Sinne erst nach rückwärts gestoßen sind und dann wiederum bis an die Nervenendigungen nach vorne gestoßen werden können, sondern daß man dasjenige, was aus dem Universum, aus dem Kosmos, von gleicher Art wie die Sinneswahrnehmungen ist, aber jetzt der übersinnlichen Welt angehört, daß man das gewahr wird, wie sonst nur die Erinnerungen.

Wird man die weltschöpferischen Kräfte gewahr, wie man sonst die Erinnerungen wahrnimmt, dann hat man imaginatives Wesen, dann erlebt man das Ätherwesen der Welt. Wird man gewahr hinter der Sprache dasjenige, was nun nicht vom Kehlkopf nach vorne hinausgeht, sondern von der anderen Seite aus dem Universum, aus dem Kosmos hereinspricht, aber an dem Kehlkopf verstummt, dann wird man durch Inspiration eine weitere Welt gewahr, der wir mit unserem dritten menschlichen Organismus, mit dem astralischen Leibe angehören.

Dabei zeigt sich allerdings eines. Hier in der physischsinnlichen Welthaben wir auf der einen Seite die physischen Vorgänge und auf der andern Seite die moralischen Impulse, die aus unserem Innern aufsteigen. Die stehen so nebeneinander, daß heute schon die Theologie gerne möchte, daß die Sinnenwelt nur sinnlich aufgefaßt werden sollte, und für die moralische Welt eine ganz andere Erkenntnisart da wäre. In dem Augenblick, wo man bis zur Inspiration vorrückt, wo man nicht nur in der Welt lebt, in der man spricht vom Kehlkopf vorwärts, sondern wo man in der Welt lebt, die da durch unseren ganzen Menschen hindurch spricht, aber am Kehlkopf verstummt, weil wir da das Tor vorschieben, wenn wir die äußere Sprache erlernen, so daß wir die äußere Sprache als ein Ersatzmittel gegen die Himmelssprache erleben — in dem Augenblick, wo wir uns in diese Welt hineinleben, die nun am Kehlkopf aufhört, dann erleben wir den Inspirationsinhalt der Welt, dann erleben wir die Geheimnisse der Welt, und dann erleben wir nicht bloß eine Natur, an die die moralischen Impulse nicht herankönnen, sondern wir erleben hinter dem natürlichen Dasein eine Welt, wo Naturimpulse, Naturgesetzmäßigkeiten und moralische Gesetzmäßigkeiten ineinander verwoben sind, wo sie eins sind. Wir haben den Schleier gehoben und haben eine Welt gefunden, in der Moralisches und Physisches ineinanderklingt. Und wir werden sehen, daß das die Welt ist, in der wir im vorirdischen Dasein waren, bevor wir zur Erde heruntergestiegen sind, in die wir wieder eintreten, nachdem wir durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen sind.