Christianity as Mystical Fact

GA 8

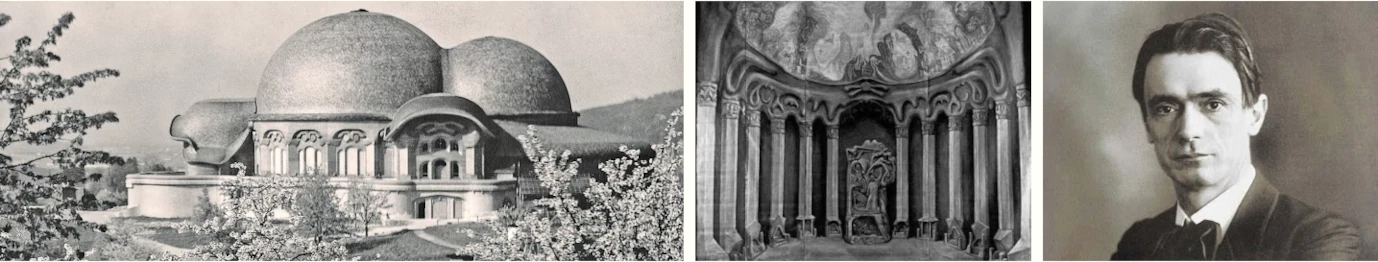

III. The Greek Sages Before Plato in the Light of Mystery Wisdom

[ 1 ] Numerous facts combined to show us that the N philosophical wisdom of the Greeks rested on the same mental basis as mystic knowledge. We understand the great philosophers only when we approach them with feelings gained through study of the Mysteries. With what veneration does Plato speak of the “secret doctrines” in the Phaedo! “And it almost seems,” he says, “as though those who have appointed the initiations for us are not such bad people after all, and that for a long time they have been enjoining upon us that anyone who reaches Hades without being initiated and sanctified falls into the mire; but that he who is purified and consecrated when he arrives dwells with the gods. For those who have to do with consecrations say that there are many thyrsus-bearers,1Thyrsus, a staff entwined with ivy and surmounted by a pine-cone, or by a bunch of vine or ivy leaves, with grapes or berries. It is an attribute of Dionysos, or the Satyrs. but few really inspired. These latter are, in my opinion, none other than those who have devoted themselves in the right way to wisdom. I myself have not missed the opportunity of becoming one of these, as far as I was able, and have striven after it in every way.”

It is only a man who is placing his own search for wisdom entirely at the disposal of the condition of soul created by initiation who could thus speak of the Mysteries. And there is no doubt that a flood of light is shed on the words of the great Greek philosophers when we illuminate them from the Mysteries.

[ 2 ] The relation of Heraclitus of Ephesus (535-475 B.C.) to the Mysteries is plainly given us in a saying about him, to the effect that his thoughts “were an impassable road”, and that anyone entering upon them without ‘ being initiated found only “dimness and darkness”; but that, on the other hand, they were “brighter than the sun” for anyone introduced to them by an initiate. And when it is said of his book that he deposited it in the temple of Artemis, this simply means that initiates alone could understand him.2Edmund Pfleiderer has already collected the historical evidence for the relation of Heraclitus to the Mysteries. Cf. his book: Die Philosophie des Heraklit von Ephesus im Lichte der Mysterienidee, Berlin, 1866. Heraclitus was called “The Obscure”, because it was only through the Mysteries that light could be thrown on his views.

[ 3 ] Heraclitus comes before us as a man who took life with the greatest seriousness. Even his features show us, if we can recall them, that he bore within himself intimate knowledge which he knew words could only suggest, not express. Out of this background arose his celebrated utterance, “All things are in flux,” which Plutarch explains thus: “We do not dip twice into the same wave, nor can we twice come in contact with the same mortal existence. For through abruptness and speed it disperses and brings together, not in succession but simultaneously.”

A man with such views has penetrated the nature of transitory things, for he has felt impelled to characterize the essence of transitoriness itself in the clearest terms. Such a description as this could not be given unless the transitory were being measured by the Eternal; and in particular, it could not be extended to man without an insight into his inner nature. Heraclitus has extended his characterization to man: “Life and death, waking and sleeping, youth and age are the same; this in changing is that, and that again this” In this sentence there is expressed full knowledge of the illusory nature of the lower personality. He says still more forcibly: “Life and death are found in our living even as in our dying.” What does this mean but that only a point of view based on the transitory can value life more than death? Dying is to pass, in order to make way for new life, but the Eternal lives in the new life, as in the old. The same Eternal appears in transitory life as in death. When we grasp this Eternal we look upon life and death with the same feeling. Life has a special value only when we have not been able to awaken the Eternal within us. The saying, “All things are in flux,” might be repeated a thousand times, but unless said in the mood of this feeling, it is empty sound. The knowledge of eternal growth is valueless if it does not detach us from temporal growth. It is the turning away from that love of life which impels toward the transitory that Heraclitus indicates in his utterance: “How can we say of our daily life, ‘We are;’ when from the standpoint of the eternal we know that ‘We are and are not’?”3Cf. Fragments of Heraclitus, No. 81. “Hades and Dionysos are one and the same,” says one of the Fragments. Dionysos, the god of joy in life, of germination and growth, to whom the Dionysiac festivals are dedicated is, for Heraclitus, the same as Hades, the god of destruction and annihilation. Only one who sees death in life and life in death, and in both the Eternal, high above life and death, can view the merits and demerits of existence in the right light. Then even imperfections become justified, for in them, too, lives the Eternal. What they are from the standpoint of the limited lower life they are only in appearance: “The gratification of men’s wishes is not necessarily a happiness for them. Illness makes health sweet and good, hunger makes food appreciated, and toil, rest” “The sea’s water is the purest and impurest, drinkable and wholesome for fishes, it is undrinkable and injurious to human beings.” Heraclitus is not primarily drawing attention to the transitoriness of earthly things, but to the splendor and majesty of the Eternal.

Heraclitus speaks vehemently against Homer and Hesiod, and the learned men of his day. He wished to show up their way of thinking which clings to the transitory. He did not desire gods endowed with qualities taken from a perishable world, and he could not regard as supreme that science which investigates the laws of growth and decay of things. For him, the Eternal speaks out of the perishable, and for this Eternal he has a profound symbol. “The harmony of the world returns upon itself, like that of the lyre and the bow.” What depths are hidden in this image! By the pressing asunder of forces and by the harmonizing of these divergent forces, unity is attained. One tone conflicts with another, but together they produce harmony. If we apply this to the spiritual world we have the thought of Heraclitus: “Immortals are mortal, mortals immortal, living the death of mortals, dying the life of the immortals.”

[ 4 ] It is man’s original guilt to cling with his cognition to the transitory. Thereby he turns away from the Eternal, and life becomes a danger for him. What happens to him comes to him through life, but its events lose their sting if he ceases to set unconditioned value on life. In that case his innocence is restored to him. It is as though he were able to return from the so-called seriousness of life to his childhood. The adult takes many things seriously with which a child merely plays, but one who really knows becomes like a child. “Serious” values lose their value when looked at from the standpoint of eternity. Life then seems like play. On this account does Heraclitus say: “Eternity is a child at play, it is the reign of a child.” Where does the original guilt lie? In taking with the utmost seri- ousness what ought not to be so taken. God has poured himself into the world of objects. If we take these objects and leave God unheeded, we take them in earnest as “the tombs of God”. We should play with them like a child, but at the same time should earn- estly strive to call forth from them the Divine that sleeps spellbound within them.

[ 5 ] Beholding of the Eternal acts like a consuming fire on ordinary speculation about the nature of things. The spirit dissolves thoughts which come through the senses; it fuses them; it is a consuming fire. This is the higher meaning of the Heraclitean thought, that fire is the primary element of all things. This thought is certainly to be taken at first as an ordinary physical explanation of the phenomena of the universe. But no one understands Heraclitus who does not think of him in the same way as Philo, living in the early days of Christianity, thought of the laws of the Bible. “There are people,” he says, “who take the written laws merely as symbols of spiritual doctrines, who diligently search for the latter, but despise the laws them- selves. I can only reprove such, for they should pay heed to both, to an understanding of the hidden meaning and to the observation of the obvious one.” If the question is discussed whether Heraclitus meant by “fire” physical fire, or whether fire for him was only a symbol of Eternal Spirit which dissolves and rebuilds all things, then a wrong construction has been put upon his thought. He meant both and neither of these things; for spirit was also alive for him in ordinary fire, and the force that is physically active in fire lives on a higher plane in the human soul, which melts in its crucible mere sense-knowledge and engenders out of this the perception of the Eternal.

[ 6 ] It is very easy to misunderstand Heraclitus. He makes strife the father of things, but only of “things”, not of the Eternal. If there were no contrasts in the world, no conflicting interests, the world of becoming, of transitory things, would not exist. But what is revealed in this antagonism, what is poured out into it, is not strife but harmony. Just because there is strife in all things, the spirit of the wise should pass over them like a breath of fire, and change them into harmony.

From this point there shines forth one of the great thoughts of Heraclitean wisdom. What is man as a personal being? From the point of view just stated Heraclitus is able to answer. Man is composed of the conflicting elements into which Divinity has poured itself. In this state he finds himself, and beyond this becomes aware of the spirit within him, the spirit which is rooted in the Eternal. But the spirit is born for man himself out of the conflict of elements, and it is the spirit also which has to calm them. In man, nature surpasses her creative limits. It is indeed the same universal force that created antagonism and the mixture of elements which afterwards by its wisdom is to do away with the conflict. Here we arrive at the eternal dualism which lives in man, the perpetual contrast between the temporal and the Eternal. Through the Eternal he has become something quite definite, and out of this he is to create something higher. He is both dependent and independent. He can participate in the Eternal Spirit whom he beholds only in the measure of the compound of elements which that Eternal Spirit has effected within him. And it is just on this account that he is called upon to fashion the Eternal out of the temporal. The spirit works within him, but works in a special way. It works out of the temporal. It is the peculiarity of the human soul that a temporal thing should be able to act like an eternal one, should work and increase in power like an eternal thing. This is why the soul is at once like a god and a worm. Man, owing to this, stands midway between God and the animal. The productive and active force within him is his daimonic element—that within him which reaches beyond himself.

“Man’s daimon is his destiny.” Thus strikingly does Heraclitus make reference to this fact.4Daimon is used here in the Greek sense. Today we would say “spirit”. He extends man’s vital essence far beyond the personal. The personality is the vehicle of the daimon, which is not confined within the limits of the personality, and for which the birth and death of the personality are of no importance. What is the relation of the daimonic element to the personality which comes and goes? The personality is only a form for the manifestation of the daimon.

One who has arrived at this wisdom looks beyond himself, backward and forward. The experience of the daimonic in himself proves to him his own immortality. And he can no longer ascribe to his daimon the sole function of occupying his personality, for the latter can be only one of the forms in which the daimon manifests itself. The daimon cannot be shut up within one personality; he has power to animate many. He is able to transform himself from one personality into another. The great idea of reincarnation springs as something obvious from the Heraclitean premises, and not only the idea, but the experience of the fact. The idea only paves the way for the experience. One who becomes conscious of the daimonic element within himself does not find it innocent and in its first stage: it has qualities. Whence do they come? Why have I certain propensities? Because other personalities have already worked upon my daimon. And what becomes of the work which I accomplish in the daimon if I am not to assume that its task ends with my personality? I am working for a future personality. Between me and the spirit of the universe, something interposes that reaches beyond me, but is not yet the same as Divinity. This something is my daimon. As my today is only the product of yesterday and my tomorrow will be the product of today, so my life is the result of a former and will be the foundation of a future one. Just as earthly man looks back to numerous yesterdays and forward to many tomorrows, so does the soul of the sage look upon many lives in his past and many in the future. The thoughts and aptitudes I acquired yesterday I use today. Is it not the same with life? Do not people enter upon the horizon of existence with the most diverse capacities? Whence this difference? Does it proceed from nothingness?

Our natural sciences take much credit to themselves for having banished miracle from our views of organic life. David Friedrich Strauss, in his Old and New Faith,5David Friedrich Strauss, Alter und Neuer Glaube. considers it a great achievement of our day that we no longer think that a perfect organic being is a miracle issuing from nothing. We comprehend perfection when we are able to explain it as a development from imperfection. The structure of an ape is no longer a miracle if we assume its ancestors to have been primitive fishes that have been gradually transformed. Let us at least accept as reasonable in the domain of spirit what seems to us to be right in the domain of nature! Is the perfect spirit to have the same antecedents as the imperfect one? Does a Goethe have the same antecedents as any Hottentot? The antecedents of an ape are as unlike those of a fish as are the antecedents of Goethe's spirit unlike those of a savage. The spiritual ancestry of Goethe’s spirit is a different one from that of the savage. The spirit has evolved as has the body. The spirit in Goethe has more progenitors than the one in a savage. Let us take the doctrine of reincarnation in this sense and we shall no longer find it unscientific. We shall be able to explain in the right way what we find in our soul, and we shall not take what we find as if it were created by a miracle. If I can write, it is owing to the fact that I learned to write. No one who has a pen in his hand for the first time can sit down and write offhand. But one who has come into the world with the stamp of genius, must he owe it to a miracle? No, even the stamp of genius must be acquired. It must have been learned. And when it appears in a person we call it spirit. This spirit too must have gone to school; its capacities in a later life were acquired in a former one.

[ 7 ] In this form, and this form only, did the thought of Eternity live in the mind of Heraclitus and other Greek sages. There was no question with them of a continuance of the immediate personality after death. Compare some verses of Empedocles (490-430 B.C.). He says of those who accept the facts of existence as miracles:

[ 8 ] Foolish and ignorant they, for they do not reach far with their thinking,

Who suppose that what has never been can really come into being,

Or that beings there be that die away and vanish completely;

It is ne’er possible for being to begin from what is non-being,

Quite impossible also that being can fade into nothing; For wherever a being is driven, there will it remain in being.

Never will those believe, who have in these things been instructed,

That the spirits of men live only while what is called life here endures,

That only so long do they live, receiving their joys and their sorrows,

But that ere they were born they were nothing, and after they die they are naught.

[ 9 ] The Greek sage never even asked whether there was an eternal element in man, but only inquired of what this element consisted and how man can nourish and cherish it in himself. For from the outset it was clear to him that man is an intermediate creation between the earthly and the Divine. There was no thought of a Divine being outside and beyond the world. The Divine lives in man but lives in him only in a human way. It is the force urging man to make himself ever more and more divine, Only one who thinks thus can say with Empedocles:

[ 10 ] When leaving thy body behind thee thou soarest up into the ether,

Then thou becomest a god, immortal, beyond the power of death.

[ 11 ] What may be done for a human life from this point of view? It may be introduced into the magic circle of the Eternal; for in man there must be forces which the merely natural life does not develop, and the life might pass away fruitless if the forces remained idle. To release them, thereby to make man like the Divine, this was the task of the Mysteries. And this was also the mission the Greek sages set themselves. In this way we can understand Plato’s utterance that “he who passes unsanctified and uninitiated into the nether-world will lie in a slough, but that he who arrives there after initiation and purification will dwell with the gods.” We have to do here with a conception of immortality the significance of which lies bound up within the universe. Everything man undertakes in order to awaken the Eternal within him he does in order to raise the value of the world’s existence. His enlightenment does not make him an idle spectator of the universe, imagining things that would be there whether he existed or not. The power of his insight is a higher one, a creative force of nature. What flashes up within him spiritually is something divine which was previously under a spell, and which, failing the knowledge he has gained, would have to lie fallow, awaiting some other exorcist. Thus the human personality does not live in and for itself but for the world. Life expands far beyond individual existence when looked at in this way. From within such a point of view we can understand utterances like that of Pindar, giving a glimpse of the Eternal: “Happy is he who has seen the Mysteries and then descends under the hollow earth. He knows the end of life, and he knows the beginning promised by Zeus.”

[ 12 ] We understand the proud features and solitary nature of sages such as Heraclitus, They were able to say proudly of themselves that much had been revealed to them, for ‘they did not attribute their knowledge to their transitory personality, but to the eternal daimon within them, Their pride had as a necessary adjunct the stamp of humility and modesty, expressed in the words, “All knowledge of perishable things is in perpetual flux like the things themselves.” Heraclitus calls the eternal universe a game: he could also call it the most serious of realities. But the word “serious” has lost its force through being applied to earthly experiences, On the other hand, the game of the Eternal leaves man that sureness in life of which he is robbed by such seriousness as derives from the transitory.

[ 13 ] A different conception of the universe from that of Heraclitus grew up, on the basis of the Mysteries, in the community founded by Pythagoras in the 6th century B.C. in Southern Italy. The Pythagoreans saw the basis of things in the numbers and geometrical figures into whose laws they made research by means of mathematics. Aristotle says of them: “They first developed mathematics; then, completely absorbed in it, they considered the roots of mathematics to be the roots of all things. Now as numbers are naturally the first thing in mathematics and they thought they saw many resemblances in numbers to things and to development,—more in numbers than in fire, earth, and water,—in this way one quality of numbers came to mean for them justice, another, the soul and spirit, another, time, and so on with all the rest. Moreover, they found in numbers the qualities and relations of harmony; and thus everything else, in accordance with its whole nature, seemed to be an image of numbers, and number seemed to be the first thing in nature.”

[ 14 ] The mathematical and scientific study of natural phenomena must always lead to a certain Pythagorean habit of thought. When a string of a certain length is struck, a particular tone is produced. If the string is shortened in certain numeric proportions, other tones will be produced. The pitch of the tones can be expressed in figures. Physics also expresses color relations in figures. When two bodies combine into one substance, it always happens that a certain definite quantity of the one body, expressible in numbers, combines with a certain definite quantity of the other. The Pythagoreans’ sense of observation was directed to such arrangements of measures and numbers in nature. Geometrical figures also play a similar role in nature. Astronomy, for instance, is mathematics applied to the heavenly bodies. One fact became important to the thought life of the Pythagoreans: that man, quite independently and purely through his mental activity, discovers the laws of numbers and figures; and yet, that when he looks around in nature, he finds that things obey the same laws he has ascertained for himself in his own mind. Man forms the idea of an ellipse, and ascertains the laws of ellipses. And the heavenly bodies move according to the laws which he has established, (It is not, of course, a question here of the astronomical views of the Pythagoreans. What may be said about these may equally be said of Copernican views in the connection now being dealt with.) Hence it follows as a direct consequence that the achievements of the human soul are not an activity apart from the rest of the world, but that in those achievements the cosmic laws are expressed. The Pythagoreans said: “The senses show man physical phenomena, but they do not show the harmonious order regulating these phenomena.” The human spirit must first find that harmonious order within itself if this spirit wishes to behold it in the outer world. The deeper meaning of the world, that which holds sway within it as ap eternal, law-obeying necessity, this makes its appearance in the human soul and becomes a present reality there. The meaning of the universe is revealed in the soul. This meaning is not to be found in what we see, hear, and touch, but in what the soul brings to light from its own unseen depths. The eternal laws are thus hidden in the depths of the soul. If we descend there, we shall find the Eternal. God, the eternal harmony of the world, is in the human soul. The soul element is not limited to the bodily substance enclosed within the skin, for what is born in the soul is nothing less than the laws by which worlds revolve in celestial space. The soul is not in the personality. The personality only serves as the organ through which the order of pervading cosmic space may express itself. There is something in the spirit of Pythagoras in what one of the Church Fathers, Gregory of Nyssa, said: It is said that human nature is something small and limited, and that God is infinite. But who dares to say that the infinity of the Godhead is limited by the boundary of the flesh, as though by a vessel? For not even during our lifetime is the spiritual nature confined within the boundaries of the flesh. The mass of the body, it is true, is limited by neighbouring parts, but the soul reaches out freely into the whole of creation by the movements of thought.”

The soul is not the personality, the soul belongs to infinity. From such a point of view the Pythagoreans must have considered that only “fools” could imagine the soul force to be exhausted with the personality.

For them, too, as for Heraclitus, the essential point was the awakening of the Eternal in the personal. Enlightened knowledge for them meant intercourse with the Eternal. The more man brought the eternal element within him into existence, the greater must he necessarily seem to the Pythagoreans. Life in their community consisted in holding intercourse with the Eternal. The object of Pythagorean education was to lead the members of the community to that intercourse. Education was therefore a philosophical initiation, and the Pythagoreans might well say that by their manner of life they were aiming at the same goal as that of the Mystery cults.

Die Griechischen Weisen vor Plato im Lichte der Mysterienweisheit

[ 1 ] Durch zahlreiche Tatsachen erkennen wir daß die philosophische Weisheit der Griechen auf demselben Gesinnungsboden stand wie die mystische Erkenntnis. Die großen Philosophen versteht man nur, wenn man an sie mit den Empfindungen herantritt, die man aus der Beobachtung der Mysterien gewonnen hat. Mit welcher Ehrerbietung spricht doch Plato im «Phädon» von den «Geheimlehren»: «Und fast scheint es, daß diejenigen, welche uns die Weihen angeordnet haben, gar nicht schlechte Leute sind, sondern schon seit langer Zeit uns andeuten, daß, wer ungeweiht und ungeheiligt in der Unterwelt anlangt, in den Schlamm zu liegen kommt; der Gereinigte aber, und der Geweihte, wenn er dort angelangt ist, bei den Göttern wohnt. Denn, sagen die, welche mit den Weihen zu tun haben, Thyrsusträger sind viele, doch echte Begeisterte nur wenig. Diese aber sind, nach meiner Meinung, keine anderen, als die sich auf rechte Weise der Weisheit beflissen haben, deren einer zu werden auch ich nach Kräften im Leben nicht versäumt, sondern mich auf alle Weise bemüht habe.» — So kann über die Weihen nur der sprechen, der sein Weisheitsstreben selbst ganz in den Dienst der Gesinnung stellte, die durch die Weihen erzeugt wurde. Und es ist ohne Zweifel, daß auf die Worte der großen griechischen Philosophen ein helles Licht fällt, wenn wir sie von den Mysterien aus beleuchten.

[ 2 ] Von Heraklit (535–475 v. Chr.) aus Ephesus ist die Beziehung zu dem Mysterienwesen ohne weiteres durch einen Ausspruch über ihn gegeben, der überliefert ist und der besagt, daß seine Gedanken «ein ungangbarer Pfad seien», daß wer zu ihnen ohne Weihe tritt, nur «Dunkel und Finsternis» finde, daß sie dagegen «heller als die Sonne» seien für den, welchen ein Myste einführt. Und wenn von seinem Buche gesagt wird, er habe es im Tempel der Artemis niedergelegt, so bedeutet auch das nichts anderes, als daß er von Eingeweihten allein verstanden werden konnte. (Edmund Pfleiderer hat bereits das Historische beigebracht, welches für das Verhältnis des Heraklit zu den Mysterien zu sagen ist. Vergleiche sein Buch «Die Philosophie des Heraklit von Ephesus im Lichte der Mysterienidee», Berlin 1886.) Heraklit wurde der «Dunkle» genannt; aus dem Grunde, weil nur der Schlüssel der Mysterien Licht in seine Anschauungen brachte.

[ 3 ] Als eine Persönlichkeit mit dem größten Lebensernst tritt uns Heraklit entgegen. Man sieht es förmlich seinen Zügen, wenn man sich sie zu vergegenwärtigen weiß, an, daß er Intimitäten der Erkenntnis in sich trug, von denen er wußte, daß alle Worte sie nur andeuten, nicht aussprechen können. Auf dem Grunde einer solchen Gesinnung erwuchs sein berühmter Ausspruch «Alles ist im Fluß», den uns Plutarch mit den Worten erklärt: «In denselben Fluß steigt man nicht zweimal, noch kann man ein sterbliches Sein zweimal berühren. Sondern durch Schärfe und Schnelligkeit zerstreut er und führt wieder zusammen, vielmehr nicht wieder und später, sondern zugleich tritt es zusammen und läßt nach, kommt und geht. » Der Mann, der solches denkt, hat die Natur der vergänglichen Dinge durchschaut. Denn er hat sich gedrängt gefühlt, das Wesen der Vergänglichkeit selbst mit den schärfsten Worten zu charakterisieren. Man kann eine solche Charakteristik nicht geben, wenn man die Vergänglichkeit nicht an der Ewigkeit mißt. Und man kann diese Charakteristik insbesondere nicht auf den Menschen ausdehnen, wenn man nicht in sein Inneres geschaut hat. Heraklit hat diese Charakteristik auch auf den Menschen ausgedehnt: «Dasselbe ist Leben und Tod, Wachen und Schlafen, Jung und Alt, dieses sich ändernd ist jenes, jenes wieder dies.» In diesem Satze spricht sich eine volle Erkenntnis von der Scheinhaftigkeit der niederen Persönlichkeit aus. Er sägt darüber noch kräftiger: «Leben und Tod ist in unserem Leben ebenso wie in unserem Sterben. » Was will das anderes besagen, als daß allein vom Standpunkte der Vergänglichkeit aus das Leben höher gewertet werden kann als das Sterben. Das Sterben ist Vergehen, um neuem Leben Platz zu machen; aber in dem neuen Leben lebt das Ewige wie in dem alten. Das gleiche Ewige erscheint im vergänglichen Leben wie im Sterben. Hat der Mensch dieses Ewige ergriffen, dann blickt er mit demselben Gefühle auf das Sterben wie auf das Leben. Nur wenn er dieses Ewige nicht in sich zu wecken vermag, hat das Leben für ihn einen besonderen Wert. Man kann den Satz «Alles ist im Fluß» tausendmal hersagen; wenn man ihn nicht mit diesem Gefühisinhalt sagt, ist er ein Nichtiges. Wertlos ist die Erkenntnis von dem ewigen Werden, wenn sie nicht unser Hängen an diesem Werden aufhebt. Es ist die Abkehrung von der nach dem Vergänglichen drängenden Lebenslust, die Heraklit mit seinem Ausspruche meint. «Wie sollen wir von unserem Tagesleben sagen: Wir sind, da wir doch vom Standpunkt des Ewigen aus wissen: Wir sind und sind nicht» (vergleiche Heraklit-Fragment Nr. 81). «Hades und Dionysos sind derselbe» heißt eines der Heraklitischen Fragmente. Dionysos, der Gott der Lebens-lust, des Keimens und Wachsens, dem die dionysischen Feste gefeiert wurden: er ist für Heraklit derselbe wie Hades, der Gott der Vernichtung, der Gott der Zerstörung. Nur wer den Tod im Leben und das Leben im Tode sieht und in beiden das Ewige, das erhaben ist über Leben und Tod, dessen Blick kann die Mängel und Vorzüge des Daseins im rechten Lichte schauen. Auch die Mängel finden dann ihre Rechtfertigung, denn auch in ihnen lebt das Ewige. Was sie vom Standpunkte des beschränkten, niederen Lebens sind, das sind sie nur scheinbar: «Den Menschen ist nicht besser zu werden, was sie wollen: Krankheit macht Gesundheit süß und gut, Hunger Sättigung, Arbeit Ruhe.» «Das Meer ist das reinste und unreinste Wasser, den Fischen trinkbar und heilsam, den Menschen untrinkbar und verderblich. » Nicht auf die Vergänglichkeit der irdischen Dinge will Heraklit in erster Linie hinweisen, sondern auf den Glanz und die Hoheit des Ewigen. -Heftige Worte sprach Heraklit gegen Homer und Hesiod und gegen die Gelehrten des Tages. Er wollte auf die Art ihres Denkens, das nur am Vergänglichen haftet, weisen. Er wollte nicht Götter mit Eigenschaften ausgestattet, die aus der vergänglichen Welt genommen sind. Und er konnte nicht eine Wissenschaft als die höchste achten, welche die Gesetze des Werdens und Vergehens der Dinge untersucht. -Für ihn spricht aus der Vergänglichkeit heraus ein Ewiges. Für dieses Ewige hat er ein tiefsinniges Symbol. «In sich zurückkehrend ist die Harmonie der Welt wie der Lyra und des Bogens. » Was alles liegt in diesem Bilde. Durch Auseinanderstreben der Kräfte und Harmonisieren der auseinandergehenden Mächte wird die Einheit erreicht. Wie widerspricht ein Ton dem andern; und doch, wie bewirkt er mit ihm zusammen die Harmonie. Man wende das auf die Geisteswelt an; und man hat Heraklits Gedanken: «Unsterbliche sind sterblich, Sterbliche unsterblich, lebend den Tod von jenen, sterbend das Leben von jenen. »

[ 4 ] Es ist die Urschuld des Menschen, wenn er am Vergänglichen mit seiner Erkenntnis haftet. Er wendet sich damit vom Ewigen ab. Das Leben wird dadurch seine Gefahr. Was ihm geschieht, geschieht ihm vom Leben. Aber dieses Geschehen verliert seinen Stachel, wenn er das Leben nicht mehr unbedingt wertet. Dann wird ihm seine Unschuld wieder zurückgegeben. Es geht ihm, wie wenn er in die Kindheit zurückkehren könnte, aus dem sogenannten Ernst des Lebens heraus. Was nimmt der Erwachsene alles ernst, womit das Kind spielt. Der Wissende aber wird wie das Kind. «Ernste» Werte verlieren ihren Wert, vom Ewigkeitsstandpunkte aus gesehen. Wie ein Spiel erscheint das Leben dann. «Die Ewigkeit», sagt deshalb Heraklit, «ist ein spielendes Kind, die Herrschaft eines Kindes. » Worin liegt die Urschuld? Sie liegt darin, daß mit höchstem Ernste genommen wird, woran sich dieser Ernst nicht heften sollte. Gott hat sich in die Welt der Dinge ergossen. Wer die Dinge ohne Gott hinnimmt, nimmt sie als «Gräber Gottes» ernst. Er müßte mit ihnen spielen wie ein Kind, aber seinen Ernst dazu verwenden, um aus ihnen das Göttliche zu holen, das in ihnen verzaubert schläft.

[ 5 ] Brennend, ja versengend wirkt das Anschauen des Ewigen auf das gewöhnliche Wähnen über die Dinge. Der Geist löst die Gedanken der Sinnlichkeit auf; er bringt sie zum Schmelzen. Er ist ein verzehrendes Feuer. Dies ist der höhere Sinn des Heraklitischen Gedankens, daß Feuer der Urstoff aller Dinge sei. Gewiß ist dieser Gedanke zunächst im Sinne einer gewöhnlichen physikalischen Erklärung der Welterscheinungen zu nehmen. Aber niemand versteht Heraklit, der nicht denkt über ihn, wie Philo, der zur Zeit der Entstehung des Christentums lebte, über die Gesetze der Bibel gedacht hat. «Es gibt Leute», sagte er, «welche die geschriebenen Gesetze nur für Sinnbilder geistiger Lehren halten, letztere mit Sorgfalt aufsuchen, erstere aber verachten; solche kann ich nur tadeln, denn sie sollten auf beides bedacht sein: auf Erkenntnis des verborgenen Sinnes und auf Beobachtung des offenen.» — Wenn man sich darüber streitet, ob Heraklit mit seinem Begriffe des Feuers das sinnliche Feuer gemeint habe, oder aber, ob ihm das Feuer nur ein Symbol des die Dinge auflösenden und wieder bildenden ewigen Geistes gewesen sei, so verkehrt man seinen Gedanken. Er hat beides gemeint; und auch keines von beiden. Denn für ihn lebte auch im gewöhnlichen Feuer der Geist. Und die Kraft, die im Feuer auf physische Art tätig ist, lebt auf höherer Stufe in der Menschenseele, die in ihren Schmelztiegeln die sinnenfällige Erkenntnis zerschmilzt und aus ihr das Anschauen des Ewigen hervorgehen läßt.

[ 6 ] Gerade Heraklit kann leicht mißverstanden werden. Er läßt den Krieg den Vater der Dinge sein. Aber dieser ist ihm eben nur der Vater der «Dinge», nicht des Ewigen. Wären nicht Gegensätze in der Welt, lebten nicht die mannigfaltigsten einander widerstreitenden Interessen, so wäre die Welt des Werdens, der Vergänglichkeit nicht. Aber was sich in diesem Widerstreit offenbart, was in ihn ausgegossen ist: das ist nicht der Krieg, das ist die Harmonie. Eben weil Krieg in allen Dingen ist, soll der Geist des Weisen wie das Feuer über die Dinge hinziehen und sie in Harmonie wandeln. Aus diesem Punkte heraus leuchtet ein großer Gedanke der Heraklitischen Weisheit. Was ist der Mensch als persönliches Wesen? Diese Frage erhält für Heraklit von diesem Punkte aus die Antwort. Aus den widerstreitenden Elementen, in welche die Gottheit sich ergossen hat, ist der Mensch gemischt. So findet er sich. Darüber wird er in sich den Geist gewahr. Den Geist, der aus dem Ewigen stammt. Dieser Geist aber wird für ihn selbst aus dem Widerstreit der Elemente heraus geboren. Aber dieser Geist soll auch die Elemente beruhigen. Im Menschen schafft die Natur über sich selbst hinaus. Es ist ja dieselbe All-Eine Kraft, die den Widerstreit, die Mischung erzeugt hat; und die weisheitsvoll diesen Widerstreit wieder beseitigen soll. Da haben wir die ewige Zweiheit, die im Menschen lebt; seinen ewigen Gegensatz zwischen Zeitlichem und Ewigem. Er ist durch das Ewige etwas ganz Bestimmtes geworden; und er soll aus diesem Bestimmten heraus ein Höheres schaffen. Er ist abhängig und unabhängig. An dem ewigen Geiste, den er schaut, kann er doch nur teilnehmen nach Maßgabe der Mischung, die der ewige Geist in ihm gewirkt hat. Und gerade deshalb ist er berufen, aus dem Zeitlichen das Ewige zu gestalten. Der Geist wirkt in ihm. Aber er wirkt in ihm auf besondere Weise. Er wirkt aus dem Zeitlichen heraus. Daß ein Zeitliches wie ein Ewiges wirkt, daß es treibt und kraftet wie ein Ewiges: das ist das Eigentümliche der Menschenseele. Das macht, daß diese einem Gotte und einem Wurme zugleich ähnlich ist. Zwischen Gott und Tier steht der Mensch dadurch mitten inne. Dies Treibende und Kraftende in ihm ist sein Dämonisches. Es ist das, was in ihm aus ihm hinausstrebt. Schlagend hat Heraklit auf diese Tatsache hingewiesen: «Des Menschen Dämon ist sein Schicksal». (Dämon ist hier im griechischen Sinn gemeint. Im modernen Sinne müßte man sagen: Geist.) So erweitert sich für Heraklit das, was im Menschen lebt, weit über das Persönliche hinaus. Dieses Persönliche ist der Träger eines Dämonischen. Eines Dämonischen, das nicht in die Grenzen der Persönlichkeit eingeschlossen ist, für welches Sterben und Geborenwerden des Persönlichen keine Bedeutung haben. Was hat dieses Dämonische mit dem zu tun, was als Persönlichkeit entsteht und vergeht? Eine Erscheinungsform nur ist das Persönliche für das Dämonische. Nach vorwärts und rückwärts blickt der Träger solcher Erkenntnis über sich selbst hinaus. Daß er Dämonisches in sich erlebt, ist ihm Zeugnis für die Ewigkeit seiner selbst. Und er darf jetzt nicht mehr diesem Dämonischen den einzigen Beruf zuschreiben, seine Persönlichkeit auszufüllen. Denn nur eine von diesen Erscheinungsformen des Dämonischen kann das Persönliche sein. Der Dämon kann sich nicht innerhalb einer Persönlichkeit abschließen. Er hat Kraft, viele Persönlichkeiten zu beleben. Von Persönlichkeit zu Persönlichkeit vermag er sich zu wandeln. Der große Gedanke der Wiederverkörperung springt wie etwas Selbstverständliches aus den Heraklitischen Voraussetzungen. Aber nicht allein der Gedanke, sondern die Erfahrung von dieser Wiederverkörperung. Der Gedanke bereitet nur für diese Erfahrung vor. Wer das Dämonische in sich gewahr wird, findet es nicht als ein unschuldvolles, erstes vor. Er findet es mit Eigenschaften. Wodurch hat es diese? Warum habe ich Anlagen? Weil an meinem Dämon schon andere Persönlichkeiten gearbeitet haben. Und was wird aus dem, was ich an dem Dämon wirke, wenn ich nicht annehmen darf, daß dessen Aufgaben in meiner Persönlichkeit erschöpft sind? Ich arbeite für eine spätere Persönlichkeit vor. Zwischen mich und die Welteinheit schiebt sich etwas, was über mich hinausreicht aber noch nicht dasselbe ist wie die Gottheit. Mein Dämon schiebt sich dazwischen. Wie mein Heute nur das Ergebnis von Gestern ist, mein Morgen nur das Ergebnis meines Heute sein wird: so ist mein Leben Folge eines andern; und es wird Grund sein für ein anderes. Wie auf zahlreiche Gestern rückwärts und auf zahlreiche Morgen vorwärts der irdische Mensch, so blickt die Seele des Weisen auf zahlreiche Leben in der Vergangenheit und zahlreiche Leben in der Zukunft. Was ich gestern erworben habe, an Gedanken, an Fertigkeiten, das benütze ich heute. Ist es nicht so mit dem Leben? Betreten die Menschen nicht mit den verschiedensten Fähigkeiten den Horizont des Daseins? Woher rührt die Verschiedenheit? Kommt sie aus dem Nichts? — Unsere Naturwissenschaft tut sich viel darauf zugute, daß sie das Wunder aus dem Gebiete unserer Anschauungen vom organischen Leben verbannt hat. David Friedrich Strauß («Der alte und der neue Glaube») bezeichnet es als große Errungenschaft der Neuzeit, daß wir ein vollkommenes organisches Geschöpf nicht mehr durch ein Wunder aus dem Nichts heraus geschaffen denken. Wir begreifen die Vollkommenheit, wenn wir sie durch Entwicklung aus dem Unvollkommenen erklären können. Der Bau des Affen ist kein Wunder mehr, wenn wir Urfische als Vorläufer des Affen annehmen dürfen, die sich allmählich gewandelt haben. Bequemen wir uns doch, für den Geist als billig hinzunehmen, was uns der Natur gegenüber als recht erscheint. Soll der vollkommene Geist ebensolche Voraussetzungen haben wie der unvollkommene? Soll Goethe die gleichen Bedingungen haben wie ein beliebiger Hottentotte? So wenig wie ein Fisch die gleichen Voraussetzungen hat wie ein Affe, so wenig hat der Goethesche Geist dieselben geistigen Vorbedingungen wie der des Wilden. Die geistige Ahnenschaft des Goetheschen Geistes ist eine andere als die des wilden Geistes. Geworden ist der Geist wie der Leib. Der Geist in Goethe hat mehr Vorfahren als der in dem Wilden. Man nehme die Lehre von der Wiederverkörperung in diesem Sinne. Man wird sie dann nicht mehr «unwissenschaftlich» finden. Aber man wird in der rechten Weise deuten, was man in der Seele findet. Man wird das Gegebene nicht als Wunder hinnehmen. Daß ich schreiben kann, verdanke ich der Tatsache, daß ich es gelernt habe. Niemand kann sich hinsetzen und schreiben, der nie vorher die Feder in der Hand gehabt hat. Aber einen «genialen Blick» soll der eine oder der andere haben auf bloß wunderbare Weise. Nein, auch dieser «geniale Blick» muß erworben sein: er muß gelernt sein. Und tritt er in einer Persönlichkeit auf, so nennen wir ihn ein Geistiges. Aber dieses Geistige hat eben auch erst gelernt; es hat sich in einem früheren Leben erworben, was es in einem späteren «kann».

[ 7 ] So, und nur so, schwebte dem Heraklit und anderen griechischen Weisen der Ewigkeitsgedanke vor. Von einer Fortdauer der unmittelbaren Persönlichkeit war bei ihnen nie die Rede. Man vergleiche eine Rede des Empedokles (490–430 v. Chr.). Er sagt von denen, die das Gegebene nur als Wunder hinnehmen:

[ 8 ] Törichte sind's, denn sie reichen nicht weit mit ihren Gedanken,

Die da wähnen, es könne Zuvor-nicht-Seiendes werden,

Oder auch etwas ganz hinsterben und völlig verschwinden.

Aus Nicht-Seiendem ist durchaus ein Entstehen nicht möglich;

Ganz unmöglich auch ist, daß Seiendes völlig vergebe;

Denn stets bleibt es ja, wohin man es eben verdränget.

Nimmer wohl wird, wer darin belehrt ist, solches vermeinen,

Daß nur 50 lange sie leben, was man nun Leben benennet,

Nur solange sie sind, und Leiden empfangen und Freuden,

Doch, eh' Menschen sie wurden und wann sie gestorben, sie

nichts sind.

[ 9 ] Der griechische Weise warf die Frage gar nicht auf, ob es ein Ewiges im Menschen gebe; sondern allein die, worinnen dieses Ewige besteht, und wie es der Mensch in sich hegen und pflegen kann. Denn von vornherein war es für ihn klar, daß der Mensch als Mittelgeschöpf zwischen Irdischem und Göttlichem lebt. Von einem Göttlichen, das außer und jenseits des Weltlichen ist, war da nicht die Rede. Das Göttliche lebt in dem Menschen; es lebt eben da nur auf menschliche Weise. Es ist die Kraft, die den Menschen treibt, sich selbst immer göttlicher und göttlicher zu machen. Nur wer so denkt, kann reden wie Empedokles:

[ 10 ] Wenn du den Leib verlassend, zum freien Äther dich schwingst,

Wirst ein unsterblicher Gott du sein, dem Tode entronnen. —

[ 11 ] Was kann unter solchem Gesichtspunkt für ein Menschenleben geschehen? Es kann in die magische Kreisordnung des Ewigen eingeweiht werden. Denn in ihm müssen Kräfte liegen, die das bloß natürliche Leben nicht zur Entwicklung bringt. Und dieses Leben könnte ungenützt vorübergehen, wenn diese Kräfte brach liegen blieben. Sie zu erschließen, den Menschen dadurch dem Göttlichen anzuähnlichen: das war die Aufgabe der Mysterien. Und das stellten sich auch die griechischen Weisen zur Aufgabe. So verstehen wir Platos Ausspruch, daß «wer ungeweiht und ungeheiligt in der Unterwelt angelangt, in den Schlamm zu liegen kommt, der Gereinigte und Geweihte aber, wenn er dort angelangt ist, bei den Göttern wohnt». Man hat es da mit einem Unsterblichkeitsgedanken zu tun, dessen Bedeutung innerhalb des Weltganzen beschlossen liegt. Alles, was der Mensch unternimmt, um in sich das Ewige zu erwecken, tut er, um den Daseinswert der Welt zu erhöhen. Er ist als ein Erkennender nicht ein müßiger Zuschauer des Weltganzen, der sich Bilder von dem macht, was auch ohne ihn da wäre. Seine Erkenntniskraft ist eine höhere, eine schaffende Naturkraft. Was in ihm geistig aufblitzt, ist ein Göttliches, das vorher verzaubert war, und das ohne seine Erkenntnis brach liegen bliebe und auf einen anderen Entzauberer warten müßte. So lebt die menschliche Persönlichkeit nicht in sich und für sich; sie lebt für die Welt. Das Leben erweitert sich über das Einzeldasein weit hinaus, wenn es so angeschaut wird. Innerhalb solcher Anschauung begreift man Sätze wie den Pindarschen, der den Ausblick ins Ewige gibt: «Selig, wer jene geschaut hat und dann unter die hohle Erde hinab-steigt; er kennt des Lebens Ende, er kennt den von Zeus verheißenen Anfang.»

[ 12 ] Man versteht die stolzen Züge und die einsame Art solcher Weisen, wie Heraklit einer war. Stolz konnten sie von sich sagen, daß ihnen vieles offenbar; denn sie schrieben ihr Wissen gar nicht ihrer vergänglichen Persönlichkeit zu, sondern dem ewigen Dämon in ihnen. Ihr Stolz hatte als notwendige Beigabe eben den Stempel der Demut und Bescheidenheit, welche die Worte ausdrücken: Alles Wissen über vergängliche Dinge ist in ewigem Flusse wie diese vergänglichen Dinge selbst. Ein Spiel nennt Heraklit die ewige Welt; er könnte sie auch den höchsten Ernst nennen. Aber das Wort Ernst ist verbraucht durch seine Anwendung auf irdische Erlebnisse. Das Spiel des Ewigen beläßt in dem Menschen die Lebenssicherheit, die ihm der Ernst benimmt, der aus dem Vergänglichen entsprossen ist.

[ 13 ] Eine andere Form der Weltanschauung als die des Heraklit ist auf der Grundlage des Mysterienwesens innerhalb der von Pythagoras im sechsten Jahrhundert v. Chr. in Unteritalien gestifteten Gemeinschaft erwachsen. Die Pythagoreer sahen in den Zahlen und Figuren, deren Gesetze sie durch die Mathematik erforschten, den Grund der Dinge. Aristoteles erzählt von ihnen: «Sie führten zuerst die Mathematik fort, und indem sie ganz darin aufgingen, hielten sie die Anfänge in ihr auch für die Anfänge aller Dinge. Da nun in dem Mathematischen die Zahlen von Natur das erste sind, und sie in den Zahlen viel Ähnliches mit den Dingen und dem Werdenden zu sehen glaubten, und zwar in den Zahlen mehr als in dem Feuer, der Erde und dem Wasser, so galt ihnen eine Eigenschaft der Zahlen als die Gerechtigkeit, eine andere als die Seele und der Geist, wieder eine andere als die Zeit, und so fort für alles übrige. Sie fanden ferner in den Zahlen die Eigenschaften und die Verhältnisse der Harmonie, und so schien alles andere, seiner ganzen Natur nach, Abbild der Zahlen und die Zahlen das erste in der Natur zu sein.»

[ 14 ] Auf einen gewissen Pythagoreismus muß die mathematisch-wissenschaftliche Betrachtung der Naturerscheinungen immer führen. Wenn eine Saite von bestimmter Länge angeschlagen wird, so entsteht ein gewisser Ton. Wird die Saite in bestimmten Zahlenverhältnissen verkürzt, so entstehen immer andere Töne. Man kann die Tonhöhen durch Zahlenverhältnisse ausdrücken, Die Physik drückt auch die Farbenverhältnisse durch Zahlen aus. Wenn sich zwei Körper zu einem Stoffe verbinden, so geschieht es immer so, daß sich eine ganz bestimmte durch Zahlen ein für allemal ausdrückbare Menge des einen Stoffes mit einer ebensolchen des anderen Stoffes verbindet. Auf solche Ordnungen nach Maß und Zahl in der Natur war der Beobachtungssinn der Pythagoreer gelenkt. Auch die geometrischen Figuren spielen eine ähnliche Rolle in der Natur. Die Astronomie zum Beispiel ist eine auf die Himmelskörper angewandte Mathematik. Was für das Vorstellungsleben der Pythagoreer wichtig wurde, das ist die Tatsache, daß der Mensch ganz für sich allein, bloß durch seine geistigen Operationen die Gesetze der Zahlen und Figuren erforscht; und daß doch, wenn er dann in die Natur hinausblickt, die Dinge den Gesetzen folgen, die er für sich in seiner Seele festgestellt hat. Der Mensch bildet für sich den Begriff einer Ellipse aus; er stellt die Gesetze der Ellipse fest. Und die Himmelskörper bewegen sich im Sinne der Gesetze, die er festgesetzt hat. (Es kommt hier natürlich nicht auf die astronomischen Anschauungen der Pythagoreer an. Was von den ihrigen gesagt werden kann, kann auch von den Kopernikanischen in der hier in Betracht kommenden Beziehung gesagt werden.) Daraus folgt ja unmittelbar, daß die Verrichtungen der Menschenseele nicht ein Treiben sind abseits von der übrigen Welt, sondern daß in diesen Verrichtungen sich das ausspricht, was als gesetzmäßige Ordnung die Welt durchzieht. Der Pythagoreer sagte sich: die Sinne zeigen dem Menschen die sinnlichen Erscheinungen. Aber sie zeigen nicht die harmonischen Ordnungen, denen die Dinge folgen. Diese harmonischen Ordnungen muß vielmehr der Menschengeist erst in sich finden, wenn er sie außen in der Welt schauen will. Der tiefere Sinn der Welt, das was in ihr als ewige, gesetzmäßige Notwendigkeit waltet: das kommt in der Menschenseele zum Vorschein, das wird in ihr gegenwärtige Wirklichkeit. In der Seele geht der Sinn der Welt auf. Nicht in dem, was man sieht, hört und tastet, liegt dieser Sinn, sondern in dem, was die Seele aus ihren tiefen Schächten zutage fördert. Die ewigen Ordnungen sind also in den Tiefen der Seele geborgen. Man steige hinunter in die Seele: und man wird das Ewige finden. Gott, die ewige Weltharmonie, ist in der Menschenseele. Nicht auf die Körperlichkeit, die in des Menschen Haut eingeschlossen ist, ist das Seelische beschränkt. Denn was in der Seele geboren wird, das sind die Ordnungen, nach denen die Welten im Himmelsraum kreisen. Die Seele ist nicht in der Persönlichkeit. Die Persönlichkeit gibt bloß das Organ ab, durch welches das, was als Ordnung den Weltenraum durchzieht, sich aussprechen kann. Es steckt etwas von dem Geist des Pythagoras in dem, was der Kirchenvater Gregor von Nyssa gesagt hat: «Allein etwas Kleines, sagt man, Begrenztes ist die menschliche Natur, unendlich aber die Gottheit, und wie wohl ist durch das Winzige das Unendliche umfaßt worden? Und wer sagt das, daß in der Umgrenzung des Fleisches wie in einem Gefäße die Unendlichkeit der Gottheit eingefaßt war? Denn nicht einmal in unserem Leben wird innerhalb der Grenzen des Fleisches die geistige Natur eingeschlossen; sondern die Masse des Körpers wird zwar durch die Nachbarteile begrenzt, die Seele aber breitet sich durch die Bewegungen des Denkens frei in der ganzen Schöpfung aus. » Die Seele ist nicht die Persönlichkeit. Die Seele gehört der Unendlichkeit an. So mußte es auch von solchem Gesichtspunkte aus für die Pythagoreer gelten, daß bloß «Törichte» wähnen können: mit der Persönlichkeit sei das Seelische erschöpft. — Auch für sie mußte es darauf ankommen, in dem Persönlichen das Ewige zu erwecken. Erkenntnis war ihnen Umgang mit dem Ewigen. Um so höher mußte ihnen der Mensch gelten, je mehr er dieses Ewige in sich zum Dasein bringt. In der Pflege des Umgangs mit dem Ewigen bestand das Leben in ihrer Gemeinschaft. Die Mitglieder dieser Gemeinschaft zu solchem Umgang zu führen, bildete die pythagoreische Erziehung. Eine philosophische Einweihung war also diese Erziehung. Und die Pythagoreer konnten wohl sagen, daß sie durch diese Lebenshaltung ein Gleiches anstrebten wie die Mysterienkulte.

The Greek Sages before Plato in the Light of Mystery Wisdom

[ 1 ] Numerous facts show us that the philosophical wisdom of the Greeks stood on the same ground of thought as mystical knowledge. We can only understand the great philosophers if we approach them with the feelings we have gained from observing the mysteries. With what reverence Plato speaks of the "secret doctrines" in the "Phaedon": "And it almost seems that those who have ordered us the consecrations are not bad people at all, but have long since indicated to us that whoever arrives in the underworld unconsecrated and unhallowed will lie in the mud; but the purified one, and the consecrated one, when he has arrived there, dwells with the gods. For, say those who have to do with the consecrations, Thyrsus bearers are many, but true enthusiasts are few. These, however, in my opinion, are none other than those who have applied themselves in the right way to wisdom, of which I too have not failed to become one in life, but have made every effort to do so." - Thus, only those can speak about the consecrations who have placed their own striving for wisdom entirely at the service of the attitude generated by the consecrations. And there is no doubt that the words of the great Greek philosophers shine a bright light when we illuminate them from the Mysteries.

[ 2 ] From Heraclitus (535-475 BC) from Ephesus, the relationship to the Mysteries is given without further ado by a saying about him which has been handed down and which states that his thoughts "are an impassable path", that he who enters them without consecration finds only "darkness and gloom", but that they are "brighter than the sun" for him whom a Mystic introduces. And when it is said of his book that he laid it down in the temple of Artemis, this also means nothing other than that it could only be understood by initiates. (Edmund Pfleiderer has already provided the historical background to Heraclitus' relationship to the Mysteries. Compare his book "Die Philosophie des Heraklit von Ephesus im Lichte der Mysterienidee", Berlin 1886.) Heraclitus was called the "Dark One" for the reason that only the key of the Mysteries brought light into his views.

[ 3 ] Heraclitus confronts us as a personality with the greatest seriousness of life. One can literally see from his features, if one knows how to visualize them, that he carried within him intimacies of knowledge of which he knew that all words can only hint at them, not express them. His famous saying "Everything is in flux", which Plutarch explains to us with the words: "One does not step into the same river twice, nor can one touch a mortal being twice. But by sharpness and swiftness it scatters and brings together again, rather not again and later, but at the same time it comes together and subsides, comes and goes. " The man who thinks this has seen through the nature of transitory things. For he has felt impelled to characterize the nature of transience itself in the sharpest terms. One cannot give such a characterization if one does not measure transience by eternity. And in particular, one cannot extend this characterization to man if one has not looked into his inner being. Heraclitus also extended this characteristic to man: "The same is life and death, waking and sleeping, young and old, this changing is that, that again this." This sentence expresses a full realization of the illusory nature of the lower personality. He saws over it even more powerfully: "Life and death are in our living as well as in our dying. " What does this mean other than that from the standpoint of transience alone life can be valued higher than death. Dying is passing away to make way for new life; but in the new life lives the eternal as in the old. The same eternal appears in transient life as in death. Once man has grasped this eternal, he looks at death with the same feelings as he does at life. Only if he is not able to awaken this eternal within himself does life have a special value for him. One can recite the sentence "Everything is in flux" a thousand times; if one does not say it with this emotional content, it is nothing. The realization of eternal becoming is worthless if it does not remove our attachment to this becoming. It is the turning away from the lust for life that urges towards the transient that Heraclitus means with his saying. "How can we say of our daily life: We are, since we know from the standpoint of the eternal: We are and are not" (compare Heraclitus fragment no. 81). "Hades and Dionysus are the same" is the title of one of the Heraclitus fragments. Dionysus, the god of lust for life, of germination and growth, to whom the Dionysian festivals were celebrated: for Heraclitus he is the same as Hades, the god of annihilation, the god of destruction. Only those who see death in life and life in death and in both the eternal, which is sublime above life and death, can see the shortcomings and advantages of existence in the right light. Even the shortcomings then find their justification, for the eternal also lives in them. What they are from the point of view of the limited, lower life, they are only seemingly so: "It is not possible for people to become better at what they want: Sickness makes health sweet and good, hunger satiety, labor rest." "The sea is the purest and most impure water, drinkable and wholesome to fish, undrinkable and corrupting to man. " Heraclitus is not primarily referring to the transience of earthly things, but to the splendor and majesty of the eternal. -Heraclitus spoke harshly against Homer and Hesiod and against the scholars of the day. He wanted to point out the nature of their thinking, which clings only to the ephemeral. He did not want to endow gods with qualities taken from the transient world. And he could not regard a science as the highest, which examines the laws of the becoming and passing away of things. -For him, something eternal speaks out of transience. He had a profound symbol for this eternity. "Returning into itself is the harmony of the world like the lyre and the bow. " What all lies in this image. Unity is achieved through the divergence of forces and the harmonization of the divergent powers. How one tone contradicts the other; and yet how, together with it, it brings about harmony. Apply this to the spiritual world; and you have Heraclitus' thought: "Immortals are mortal, mortals immortal, living the death of those, dying the life of those. "

[ 4 ] It is man's guilt when he clings to the ephemeral with his knowledge. He thus turns away from the eternal. Life thus becomes his danger. What happens to him happens to him from life. But this event loses its sting when he no longer necessarily values life. Then his innocence is returned to him. He feels as if he could return to his childhood, out of the so-called seriousness of life. The adult takes everything seriously that the child plays with. But the knowledgeable person becomes like the child. "Serious" values lose their value from the point of view of eternity. Life then seems like a game. "Eternity," says Heraclitus, "is a child at play, the dominion of a child. " Wherein lies the primal guilt? It lies in the fact that what this seriousness should not attach itself to is taken with the utmost seriousness. God has poured Himself into the world of things. He who accepts things without God takes them seriously as "graves of God". He would have to play with them like a child, but use his seriousness to bring out of them the divine that sleeps enchanted within them.

[ 5 ] The contemplation of the Eternal has a burning, even searing effect on the ordinary contemplation of things. The spirit dissolves the thoughts of sensuality; it melts them. It is a consuming fire. This is the higher meaning of the Heraclitean thought that fire is the primordial substance of all things. Certainly this thought is to be taken at first in the sense of an ordinary physical explanation of world phenomena. But no one understands Heraclitus who does not think about him as Philo, who lived at the time of the emergence of Christianity, thought about the laws of the Bible. "There are people," he said, "who regard the written laws only as symbols of spiritual doctrines, seek the latter with care, but despise the former; such I can only rebuke, for they should be concerned with both: with knowledge of the hidden meaning and with observation of the open." - If one argues about whether Heraclitus meant sensual fire with his concept of fire, or whether fire was only a symbol of the eternal spirit that dissolves and re-forms things, one is reversing his thought. He meant both, and neither. For for him, the spirit also lived in ordinary fire. And the power that is physically active in fire lives at a higher level in the human soul, which melts sensual knowledge in its crucibles and allows the vision of the eternal to emerge from it.

[ 6 ] Heraclitus in particular can easily be misunderstood. He lets war be the father of all things. But for him it is only the father of "things", not of the eternal. If there were not opposites in the world, if there were not the most diverse conflicting interests, the world of becoming, of transience, would not be. But what is revealed in this conflict, what is poured into it: that is not war, that is harmony. Precisely because there is war in all things, the spirit of the wise man should pass over things like fire and transform them into harmony. From this point a great thought of Heraclitean wisdom shines forth. What is man as a personal being? For Heraclitus, this question receives its answer from this point. Man is a mixture of the conflicting elements into which the Godhead has poured itself. This is how he finds himself. Above this he becomes aware of the spirit within himself. The spirit that comes from the Eternal. But this spirit is born for him out of the conflict of the elements. But this spirit should also calm the elements. In man, nature creates beyond itself. It is the same All-One Power that has created the conflict, the mixture; and which is to wisely eliminate this conflict again. Here we have the eternal duality that lives in man; his eternal opposition between the temporal and the eternal. Through the eternal he has become something quite definite; and out of this definite he is to create something higher. It is dependent and independent. He can only participate in the eternal spirit, which he beholds, according to the mixture that the eternal spirit has worked in him. And this is precisely why he is called to create the eternal from the temporal. The spirit works in him. But it works in him in a special way. He works out of the temporal. That a temporal thing works like an eternal thing, that it drives and forces like an eternal thing: that is the peculiarity of the human soul. This makes it similar to a god and a worm at the same time. Man thus stands in the middle between God and animal. This driving and powerful force in him is his demonic nature. It is that which strives out of him. Heraclitus made a striking reference to this fact: "Man's demon is his destiny". (Demon is meant here in the Greek sense. In the modern sense one would have to say: spirit). Thus, for Heraclitus, what lives in man extends far beyond the personal. This personal is the carrier of a demonic. A demonic that is not enclosed within the boundaries of the personality, for which the death and birth of the personal have no meaning. What does this demonic have to do with that which arises and passes away as personality? The personal is only one manifestation of the demonic. Forward and backward, the bearer of such knowledge looks beyond himself. The fact that he experiences the demonic in himself is a testimony to the eternity of himself. And he may no longer ascribe to this demonic the only vocation to fill his personality. For only one of these manifestations of the demonic can be the personal. The demon cannot close itself off within one personality. It has the power to animate many personalities. It is able to change from personality to personality. The great idea of re-embodiment leaps out of the Heraclitean premises like something self-evident. But not only the thought, but the experience of this re-embodiment. Thought only prepares for this experience. Whoever becomes aware of the demonic in himself does not find it as an innocent, first one. He finds it with qualities. Why does it have these? Why do I have attachments? Because other personalities have already worked on my demon. And what becomes of what I work on the demon if I cannot assume that its tasks in my personality are exhausted? I am working for a later personality. Something interposes itself between me and the world unity which reaches beyond me but is not yet the same as the Godhead. My demon interposes itself. Just as my today is only the result of yesterday, my tomorrow will only be the result of my today: so my life is the consequence of another; and it will be the reason for another. As the earthly man looks backwards to numerous yesterdays and forwards to numerous tomorrows, so the soul of the wise man looks forward to numerous lives in the past and numerous lives in the future. What I acquired yesterday, in thoughts, in skills, I use today. Is it not so with life? Don't people enter the horizon of existence with the most diverse abilities? Where does this diversity come from? Does it come from nothing? - Our natural science takes great credit for the fact that it has banished the miraculous from the realm of our views of organic life. David Friedrich Strauss ("The Old and the New Faith") describes it as a great achievement of modern times that we no longer think of a perfect organic creature as having been created by a miracle out of nothing. We understand perfection when we can explain it through development from the imperfect. The structure of the ape is no longer a miracle if we can assume that prehistoric fish were the forerunners of the ape, which gradually evolved. Let us be comfortable in accepting as fair for the spirit what appears to us to be right for nature. Should the perfect spirit have the same conditions as the imperfect one? Should Goethe have the same conditions as any Hottentot? As little as a fish has the same preconditions as an ape, so little does the Goethean spirit have the same spiritual preconditions as that of the savage. The spiritual ancestry of the Goethean spirit is different from that of the wild spirit. The spirit has become like the body. The spirit in Goethe has more ancestors than that in the wild spirit. Take the doctrine of re-embodiment in this sense. One will then no longer find it "unscientific". But one will interpret in the right way what one finds in the soul. One will not accept what is given as a miracle. I owe the fact that I can write to the fact that I have learned it. No one can sit down and write who has never held a pen in his hand before. But one or the other is said to have an "ingenious eye" in a merely miraculous way. No, this "ingenious eye" must also be acquired: it must be learned. And when it appears in a personality, we call it a spiritual. But this spiritual has also first learned; it has acquired in an earlier life what it "can" do in a later one.

[ 7 ] This, and only this, is how Heraclitus and other Greek sages envisioned the idea of eternity. They never spoke of the continuation of the immediate personality. Compare a speech by Empedocles (490-430 BC). He says of those who accept the given only as miracles:

[ 8 ] Foolish are they, for they do not reach far with their thoughts,

who imagine that something that has not existed before can become,

or that something can die and disappear completely.

It is quite impossible for something that does not exist to come into being;

It is also quite impossible for something that exists to disappear completely;

for it always remains wherever it is displaced.

No one who is instructed in this will ever think so,

That they only live for 50 years, which is now called life,

Only as long as they are, and receive sufferings and joys,

But before they became men and when they died, they

are nothing.

[ 9 ] The Greek sage did not raise the question of whether there is something eternal in man, but only the question of what this eternal consists of and how man can nurture it within himself. For it was clear to him from the outset that man lives as a middle creature between the earthly and the divine. There was no question of a divine that is outside and beyond the worldly. The divine lives in man; it lives there only in a human way. It is the power that drives man to make himself ever more divine and more divine. Only those who think like this can speak like Empedocles:

[ 10 ] When you leave the body, swinging to the free ether,

You will be an immortal god, escaped from death. -

[ 11 ] What can happen to a human life from such a point of view? It can be initiated into the magical circular order of the eternal. For in it must lie powers which the merely natural life does not bring to development. And this life could pass by unused if these powers were to lie fallow. The task of the mysteries was to open them up, to bring man closer to the divine. And this was also the task of the Greek sages. This is how we understand Plato's saying that "he who arrives in the underworld unconsecrated and unsanctified comes to lie in the mud, but the purified and consecrated, when he arrives there, dwells with the gods". Here we are dealing with a concept of immortality whose meaning is decided within the world as a whole. Everything that man undertakes to awaken the eternal in himself, he does in order to increase the existence value of the world. As a cognizer, he is not an idle spectator of the world as a whole, who makes images of what would also be there without him. His power of cognition is a higher, creative force of nature. What flashes forth spiritually in him is a divine that was previously enchanted, and which without his cognition would lie fallow and have to wait for another disenchanter. Thus the human personality does not live in itself and for itself; it lives for the world. Life expands far beyond individual existence when it is viewed in this way. Within such a view, one understands sentences such as Pindar's, which gives a view into eternity: "Blessed is he who has seen those and then descends below the hollow earth; he knows the end of life, he knows the beginning promised by Zeus."

[ 12 ] One understands the proud features and the solitary nature of such wise men as Heraclitus was. They could proudly say of themselves that many things were obvious to them; for they did not attribute their knowledge to their transient personality, but to the eternal demon within them. Their pride had as a necessary addition the stamp of humility and modesty which the words express: All knowledge of transitory things is in eternal flux like these transitory things themselves. Heraclitus calls the eternal world a game; he could also call it the highest seriousness. But the word seriousness is consumed by its application to earthly experiences. The play of the eternal leaves in man the certainty of life that the seriousness that has sprung from the transient deprives him of.

[ 13 ] A different form of worldview to that of Heraclitus emerged on the basis of the Mystery System within the community founded by Pythagoras in the sixth century BC in Lower Italy. The Pythagoreans saw the reason for things in the numbers and figures, whose laws they explored through mathematics. Aristotle says of them: "They first carried on mathematics, and being completely absorbed in it, they considered the beginnings in it to be the beginnings of all things. Since, then, numbers are by nature the first thing in mathematics, and since they believed that numbers had much in common with things and things that come into being, and indeed more in numbers than in fire, earth and water, they regarded one property of numbers as justice, another as the soul and the spirit, yet another as time, and so on for everything else. They also found in numbers the properties and relationships of harmony, and so everything else, in its entire nature, seemed to be the image of numbers and numbers the first thing in nature."

[ 14 ] The mathematical-scientific consideration of natural phenomena must always lead to a certain Pythagoreanism. If a string of a certain length is struck, a certain tone is produced. If the string is shortened in certain numbers, different tones are always produced. Pitches can be expressed by numerical ratios; physics also expresses color ratios by numbers. When two bodies combine to form a substance, it always happens in such a way that a very specific quantity of one substance, which can be expressed once and for all by numbers, combines with a similar quantity of the other substance. The Pythagoreans' sense of observation was directed towards such orders of measure and number in nature. Geometric figures also play a similar role in nature. Astronomy, for example, is mathematics applied to the celestial bodies. What became important for the imaginative life of the Pythagoreans is the fact that man investigates the laws of numbers and figures entirely for himself, merely through his mental operations; and yet, when he then looks out into nature, things follow the laws which he has established for himself in his soul. Man forms for himself the concept of an ellipse; he establishes the laws of the ellipse. And the celestial bodies move according to the laws that he has established. (Of course, the astronomical views of the Pythagoreans are not relevant here. What can be said of theirs can also be said of the Copernican ones in the respect under consideration here). From this it follows directly that the activities of the human soul are not a drifting apart from the rest of the world, but that in these activities is expressed that which pervades the world as a lawful order. The Pythagorean said to himself: the senses show man the sensual phenomena. But they do not show the harmonious order that things follow. Rather, the human spirit must first find these harmonious orders within itself if it wants to see them outside in the world. The deeper meaning of the world, that which rules in it as an eternal, lawful necessity: that comes to light in the human soul, that becomes present reality in it. The meaning of the world emerges in the soul. This meaning does not lie in what one sees, hears and feels, but in what the soul brings to light from its deep shafts. The eternal orders are therefore hidden in the depths of the soul. Descend into the soul and you will find the eternal. God, the eternal harmony of the world, is in the human soul. The soul is not limited to the physicality that is enclosed in the human skin. For what is born in the soul are the orders according to which the worlds in heavenly space revolve. The soul is not in the personality. The personality merely provides the organ through which that which pervades the world space as order can express itself. There is something of the spirit of Pythagoras in what the Church Father Gregory of Nyssa said: "Only something small, they say, limited is human nature, but infinite is the Godhead, and how can the infinite be encompassed by the tiny? And who says that the infinity of the Godhead was enclosed in the bounds of the flesh as in a vessel? For not even in our life is the spiritual nature enclosed within the limits of the flesh; but the mass of the body is indeed limited by the neighboring parts, but the soul, through the movements of thought, spreads itself freely throughout all creation. " The soul is not the personality. The soul belongs to infinity. From this point of view it must have been true of the Pythagoreans that only the "foolish" could imagine that the soul is exhausted by the personality. - For them, too, it had to be a matter of awakening the eternal in the personal. For them, knowledge was contact with the eternal. The more man brought this eternal into existence within himself, the higher he had to be regarded by them. Life in their community consisted of cultivating contact with the eternal. To lead the members of this community to such contact was the Pythagorean education. This education was therefore a philosophical initiation. And the Pythagoreans could well say that through this attitude to life they were striving for the same thing as the mystery cults.