Goethean Science

GA 1

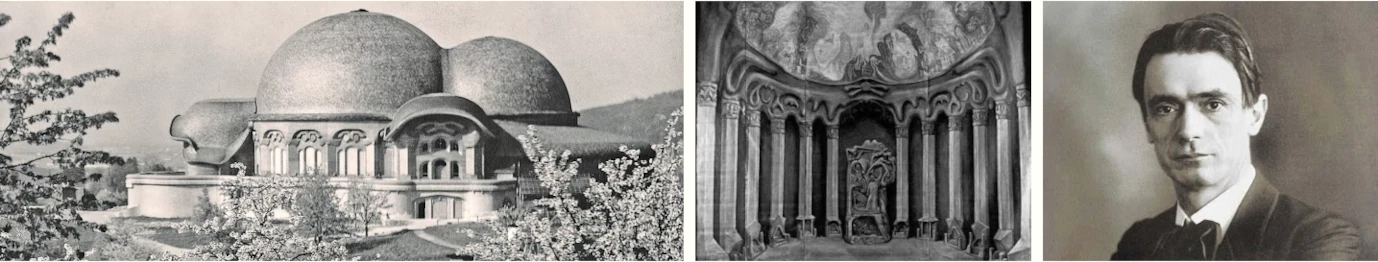

3. How Goethe's Thoughts on the Development of the Animals Arose

[ 1 ] Lavater's great work Physiognomical Fragments for Furthering Human Knowledge and Human Love 17Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe appeared during the years 1775–1778. Goethe had taken a lively interest in it, not only through the fact that he oversaw its publication, but also by making contributions to it himself. But what is of particular interest now is that, within these contributions, we can already find the germ of his later zoological works.

[ 2 ] Physiognomy sought, in the outer form of the human being, to know his inner nature, his spirit. One studied the human shape, not for its own sake, but rather as an expression of the soul. Goethe's sculptural spirit, born to know outer relationships, did not stop there. As he was in the middle of those studies that treated outer form only as a means of knowing the inner being, there dawned on him the independent significance of the former, the shape. We see this from his articles on animal skulls written in 1776, that we find inserted into the second section of the second volume of the Physiognomical Fragments. During that year, he is reading Aristotle on physiognomy, finds himself stimulated by it to write the above articles, but at the same time attempts to investigate the difference between the human being and the animals. He finds this difference in the way the whole human structure brings the head into prominence, in the lofty development of the human brain, toward which all the members of the body point, as though to their central place: “How the whole form stands there as supporting column for the dome in which the heavens are to be reflected.” He finds the opposite of this now in animal structure. “The head merely hung upon the spine! The brain, as the end of the spinal cord, has no more scope than is necessary for the functioning of the animal spirits and for directing a creature whose senses are entirely within the present moment.” With these indications, Goethe has raised himself above the consideration of the individual connections between the outer and inner being of man, to the apprehension of a great whole and to a contemplation of the form as such. He arrived at the view that the whole of man's structure forms the basis of his higher life manifestations, that within the particular nature of this whole, there lie the determining factors that place man at the peak of creation. What we must bear in mind above everything else in this is that Goethe seeks the animal form again in the perfected human one; except that, with the former, the organs that serve more the animal functions come to the fore, are, as it were, the point toward which the whole structure tends and which the structure serves, whereas the human structure particularly develops those organs that serve spiritual functions. We find here already: What hovers before Goethe as the animal organism is no longer this or that sense-perceptible real organism, but rather an ideal one, which, with the animals, develops itself more toward the lower side, and with man toward a higher one. Here already is the germ of what Goethe later called the typus, and by which he did not mean “any individual animal,” but rather the “idea” of the animal. And even more: Here already we find the echo of a law that he enunciated later and that is very significant in its implications—to the effect, namely, “that diversity of form springs from the fact that a preponderance is granted to this or that part over the others.” Here already, the contrast between animal and man is sought in the fact that an ideal form develops itself in two different directions, that in each case, one organ system gains a preponderance and the whole creature receives its character from this.

[ 3 ] In the same year (1776), we also find, however, that Goethe becomes clear about the starting point for someone who wants to study the form of the animal organism. He recognized that the bones are the foundations of its formations, a thought he later upheld by definitely taking the study of bones as his starting point in anatomical work. In this year he writes down a sentence that is important in this respect: “The mobile parts form themselves according to them (the bones)—or better, with them—and come into play only insofar as the solid parts allow.” And a further indication in Lavater's physiognomy (“It may already have been noticed that I consider the bony system to be the basic sketch of the human being, the skull to be the fundamental element of the bony system, and all fleshy parts to be hardly more than the colour on this drawing.”) may very well have been written under the stimulus of Goethe, who often discussed these things with Lavater. These views are in fact identical to indications written down by Goethe. But Goethe now makes a further observation about this, which we must particularly take into consideration: “This statement (that one can see from the bones, and indeed most strongly of all from the skull, how the bones are the foundations of the form) which here (with respect to the animals) is indisputable, will meet with serious contradiction when applied to the dissimilarity of human skulls.” What is Goethe doing here other than seeking the simpler animal again within the complex human being, as he later expressed it (1795)! From this we can gain the conviction that the basic thoughts upon which Goethe's thoughts on the development of animal form were later to be built up had already established themselves in him out of his occupation with Lavater's physiognomy in the year 1776.

[ 4 ] In this year, Goethe's study of the particulars of anatomy also begins. On January 22, 1776, he writes to Lavater: “The duke had six skulls sent to me; have noticed some marvelous things which are at your honor's disposal, if you have not found them without me.” His connections with the university in Jena gave him further stimulus to a more thorough study of anatomy. We find the first indications of this in the year 1781. In his diary, published by Keil, under the date October 15, 1781, Goethe notes that he went to Jena with old Einsiedel and studied anatomy there. At Jena there was a scholar who furthered Goethe's studies immensely: Loder. This same man then also introduces him further into anatomy, as Goethe writes to Frau von Stein on October 29, 1781,18“A troublesome service of love that I have undertaken is bringing me closer to my passion. Loder is explaining all the bones and muscles to me, and I will grasp a great deal within a few days.” and to Karl August on November 4.19“He (Loder) has demonstrated osteology and myology for me during these eight days, which we have used almost entirely for this purpose; as much, in fact, as my attentiveness could stand.” To the latter he now also expressed his intention of “explaining the skeleton,” to the “young people” in the Art Academy, and of “leading them to a knowledge of the human body.” He adds: “I do it both for my sake and for theirs; the methods I have chosen will make them, over this winter, fully familiar with the basic pillars of the body.” The entries in Goethe's diary show that he actually did give these lectures, ending them on January 16. There must have been many discussions with Loder about the structure of the human body during this same period. Under the date of January 6, the diary notes: “Demonstration of the heart by Loder.” Just as we now have seen that in 1776 Goethe was already harboring far-reaching thoughts about the structure of animal organization, so we cannot doubt for a moment that his present thorough study of anatomy raised itself beyond the consideration of the particulars to higher points of view. Thus he writes to Lavater and Merck on November 14, 1781 that he is treating “bones as a text to which everything living and everything human can be appended.” As we consider a text, pictures and ideas take shape in our spirit that seem to be called forth. to be created by the text. Goethe treated the bones as just such a text; i.e., as he contemplates them, thoughts arise in him about everything living and everything human. During these contemplations, therefore. definite ideas about the formation of the organism must have struck him. Now we have an ode by Goethe, from the year 1782, “The Divine,” which lets us know to some extent how he thought at the time about the relationship of the human being to the rest of nature. The first verse reads

Noble be man,

Helpful and good!

For that alone

Distinguishes him

From all the beings

That we know.

[ 5 ] Having grasped the human being in the first two lines of this verse according to his spiritual characteristics, Goethe states that these alone distinguish him from all the other beings of the world. This “alone” shows us quite clearly that Goethe considered man, in his physical constitution, to be absolutely in conformity with the rest of nature. The thought, to which we already drew attention earlier, becomes ever more alive in him, that one basic form governs the shape of the human being as well as of the animals, that the basic form only mounts to such perfection in man's case that it is capable of being the bearer of a free spiritual being. With respect to his sense-perceptible characteristics, the human being must also, as the ode goes on to state:

By iron laws

Mighty, eternal

His existence's

Circle complete.

[ 6 ] But in man these laws develop in a direction that makes it possible for him to do the “impossible”:

He distinguishes,

Chooses and judges;

He can the moment

Endow with duration.

[ 7 ] Now we must also still bear in mind that while these views were developing ever more definitely in Goethe, he stood in lively communication with Herder, who in 1783 began to write his Ideas on a Philosophy of the History of Mankind. This work might also be said to have arisen out of the discussions between these two men, and many an idea must be traced back to Goethe. The thoughts expressed here are often entirely Goethean, although stated in Herder's words, so we can draw from them a trustworthy conclusion about Goethe's thoughts at that time.

[ 8 ] Now in the first part of his book, Herder holds the following view about the nature of the world. A principle form must be presupposed that runs through all beings and realizes itself in different ways. “From stone to crystal, from crystal to metals, from these to plant creation, from plants to animal, from it to the human being, we saw the form of organization ascend, and saw along with it the forces and drives of the creature diversify and finally all unite themselves in the form of man, insofar as this form could encompass them.” The thought is perfectly clear: An ideal typical form, which as such is not itself sense-perceptibly real, realizes itself in an endless number of spatially separated entities with differing characteristics all the way up to man. At the lower levels of organization, this ideal form always realizes itself in a particular direction; the ideal form develops in a particular way according to this direction. When this typical form ascends as far as man, it brings together all the developmental principles—which it had always developed only in a one-sided way in the lower organisms and had distributed among different entities—in order to form one shape. From this, there also follows the possibility of such high perfection in the human being. In man's case, nature bestowed upon one being what, in the case of the animals, it had dispersed among many classes and orders. This thought worked with unusual fruitfulness upon the German philosophy that followed. To elucidate this thought, let us mention here the description that Oken later gave of the same idea. In his Textbook of Natural Philosophy 20Lehrbuch der Naturphilosophie, he says. “The animal realm is only one animal; i.e., it is the representation of animalness with all its organs existing each as a whole in itself. An individual animal arises when an individual organ detaches itself from the general animal body and yet carries out the essential animal functions. The animal realm is merely the dismembered highest animal: man. There is only one human kind, only one human race, only one human species, just because man is the whole animal realm.” Thus there are, for example, animals in which the organs of touch are developed, whose whole organization, in fact, tends toward the activity of touch and finds its goal in this activity; and other animals in which the instruments for eating are particularly developed, and so forth; in short, with every species of animal, one organ system comes one-sidedly to the fore; the whole animal merges into it; everything else about the animal recedes into the background. Now in human development, all the organs and organ systems develop in such a way that one allows the other enough space to develop freely, that each one retires within those boundaries that seem necessarily to allow all the others to come into their own in the same way. In this way, there arises a harmonious interworking of the individual organs and systems into a harmony that makes man into the most perfect being, into the being that unites the perfections of all other creatures within itself. These thoughts now also formed the content of the conversations of Goethe with Herder, and Herder gives expression to them in the following way: that “the human race is to be regarded as the great confluence of lower organic forces that, in him, were to arrive at the forming of humanity.” And in another place: “And so we can assume: that man is a central creation among the animals, i.e., that he is the elaborated form in which the traits of all the species gather around him in their finest essence.”

[ 9 ] In order to indicate the interest Goethe took in Herder's work Ideas on a Philosophy of the History of Mankind, let us cite the following passage from a letter of Goethe to Knebel in December 8, 1783: “Herder is writing a philosophy of history, such as you can imagine, new from the ground up. We read the first chapters together the day before yesterday; they are exquisite ... world and natural history is positively rushing along with us now.” Herder's expositions in Book 3, Chapter VI, and in Book 4, Chapter I, to the effect that the erect posture inherent in the human organization and everything connected with it is the fundamental prerequisite for his activity of reason—all this reminds us directly of what Goethe indicated in 1776 in the second section of the second volume of Lavater's Physiognomical Fragments about the generic difference between man and the animals, which we have already mentioned above. This is only an elaboration of that thought. All this justifies us, however, in assuming that in the main Goethe and Herder were in agreement all that time (1783 ff.) with respect to their views about the place of the human being m nature.

[ 10 ] But this basic view requires now that every organ, every part of an animal, must also be able to be found again in man, only pushed back within the limits determined by the harmony of the whole. To be sure, a certain bone, for example, must achieve a definite form in a particular species, must become predominant there, but this bone must also at least be indicated in all other species; it must in fact also not be missing in man. If, in a certain species, the bone takes on a form appropriate to it by virtue of its own laws, then, in man the bone must adapt itself to the whole, must accommodate its own laws of development to those of the whole organism. But it must not be lacking, if a split is not to occur in nature by which the consistent development of a type would be interrupted.

[ 11 ] This is how the matter stood with Goethe, when all at once he became aware of a view that totally contradicted this great thought. The learned men of that time were chiefly occupied with finding traits that would distinguish one species of animal from another. The difference between animals and man was supposed to consist in the fact that the former have a little bone, the intermaxillary bone, between the two symmetrical halves of the upper jaw, which holds the upper incisors and supposedly is lacking in man. In the year 1782, when Merck was beginning to take a lively interest in osteology and was turning for help to some of the best-known scholars of that time, he received from one of them, the distinguished anatomist Sömmerring, on October 8,1782, the following information about the difference between animal and man: “I wish you had consulted Blumenbach on the subject of the intermaxillary bone, which, other things being equal, is the only bone that all the animals have, from the ape on, including even the orangutan, but that is never found in man; except for this bone, there is nothing keeping you from being able to transfer everything man has onto the animals. I enclose therefore the head of a doe in order to convince you that this os intermaxillare (as Blumenbach calls it) or os incisivum (as Camper calls it) is present even in animals having no incisors in the upper jaw.” Although Blumenbach found in the skulls of unborn or young children a trace quasi rudimentum of the ossis intermaxillaris—indeed, had once found in one such skull two fully separated little kernels of bone as actual intermaxillary bones—still he did not acknowledge the existence of any such bone. He said about this: “There is a world of difference between it and the true osse intermaxillari.” Camper, the most famous anatomist of the time, was of the same view. He referred to the intermaxillary bone, for example, as having “never been found in a human being, not even in the negro.”21In: Natural Scientific Discussions on the Orangutan (“Natuurkundige verhandelingen over den orang outang”) Merck held Camper in the deepest admiration and occupied himself with his writings.

[ 12 ] Not only Merck, but also Blumenbach and Sömmerring were in communication with Goethe. His correspondence with Merck shows us that Goethe took the deepest interest in Merck's study of bones and shared his own thoughts about these things with him. On October 27, 1782, he asked Merck to write him something about Camper's incognitum,22An animal, see page 38—Ed. and to send him Camper's letters. Furthermore, we must note a visit of Blumenbach in Weimar in April, 1783. In September of the same year, Goethe goes to Göttingen in order to visit Blumenbach and all the professors there. On September 28, he writes to Frau von Stein: “I have decided to visit all the professors and you can imagine how much running about it requires to make the rounds in a few days.” He goes up to Kassel where he meets with Forster and Sömmerring. From there he writes to Frau von Stein on October 2: “I am seeing very fine and good things and am being rewarded for my quiet diligence. The happiest news is that I can now say that I am on the right path and from now on nothing is lost.”

[ 13 ] It is in the course of these activities that Goethe must first have become aware of the prevailing views about the intermaxillary bone. To his way of looking at things, these views must right away have seemed erroneous. The typical basic form, according to which all organisms must be built, would thereby be destroyed. For Goethe, there could be no doubt that this part, which to a more or less developed degree is to be found in all higher animals, must also have its place in the development of the human form, and would only recede in man because the organs of food-intake in general recede before the organs serving mental functions. By virtue of his whole spiritual orientation, Goethe could not think otherwise than that an intermaxillary bone must also be present in man. It was only a matter of proving this empirically, of finding what form this bone takes in man and to what extent it adapts itself to the whole of his organism. He succeeded in finding this proof in the spring of 1784, together with Loder, with whom he compared human and animal skulls in Jena. On March 27, he reported the matter to both Frau von Stein23“An exquisite pleasure has been granted me; I have made an anatomical discovery that is important and beautiful.” and to Herder.24“I have found—not silver or gold, but something that gives me inexpressible joy—the os intermaxillare in man!”

[ 14 ] Now this individual discovery, compared to the great thought by which it is sustained should not be overvalued: for Goethe also, its value lay only in the fact that it cleared away a preconception that seemed to hinder his ideas from being consistently pursued right into the farthest details of an organism. Goethe also never regarded it as an individual discovery, but always only in connection with his larger view of nature. This is how we must understand it when, in the above mentioned letter to Herder, he says: “It should heartily please you also, for it is like the keystone to man; it is not lacking; it is there too! And how!” And right away he reminds his friend of the wider perspective: “I thought of it also in connection with your whole picture, how beautiful it will be there.” For Goethe, it could make no sense to assert that the animals have an intermaxillary bone but that man has none. If it lies within the forces that shape an organism to insert an intermediary bone between the two upper jaw bones of animals, then these same forces must also be active in man, at the place where that bone is present in animals, and working in essentially the same way except for differences in outer manifestation. Since Goethe never thought of an organism as a dead, rigid configuration, but rather always as going forth out of its inner forces of development, he had to ask himself: What are these forces doing within the upper jaw of man? It could definitely not be a matter of whether the intermaxillary is present or not, but only of what it is like, of the form it has taken. And this had to be discovered empirically.

[ 15 ] The thought of writing a more comprehensive work on nature now made itself felt more and more in Goethe. We can conclude this from different things he said. Thus he writes to Knebel in November 1784, when he sends him the treatise on his discovery: “I have refrained from showing yet the result, to which Herder already points in his ideas, which is, namely, that one cannot find the difference between man and animal in the details.” Here the important point is that Goethe says he has refrained from showing the basic thought yet; he wants to do this therefore later, in a larger context. Furthermore, this passage shows us that the basic thoughts that interest us in Goethe above all—the great ideas about the animal typus—were present long before that discovery. For, Goethe admits here himself that indications of them are already to be found in Herder's ideas; the passages, however, in which they occur were written before the discovery of the intermaxillary bone. The discovery of the intermaxillary bone is therefore only a result of these momentous views. For people who did not have these views, the discovery must have remained incomprehensible. They were deprived of the only natural, historic characteristic by which to differentiate man from the animals. They had little inkling of those thoughts which dominated Goethe and which we earlier indicated: that the elements dispersed among the animals unite themselves in the one human form into a harmony; and thus, in spite of the similarity of the individual parts, they establish a difference in the whole that bestows upon man his high rank in the sequence of beings. They did not look at things ideally, but rather in an externally comparative way; and for this latter approach, to be sure, the intermaxillary bone was not there in man. They had little understanding for what Goethe was asking of them: to see with the eyes of the spirit. That was also the reason for the difference in judgment between them and Goethe. Whereas Blumenbach, who after all also saw the matter quite clearly, came to the conclusion that “there is a world of difference between it and the true ‘osse intermaxillari’,” Goethe judged the matter thus: How can an outer diversity, no matter how great, be explained in the face of the necessary inner identity? Apparently Goethe wanted to elaborate this thought now in a consistent manner and he did occupy himself a great deal with this, particularly in the years immediately following. On May 1, 1784, Frau von Stein writes to Knebel: “Herder's new book makes it likely that we were first plants and animals ... Goethe is now delving very thoughtfully into these things, and each thing that has once passed through his mind becomes extremely interesting.” To what extent there lived in Goethe the thought of presenting his views on nature in a larger work becomes particularly clear to us when we see that, with every new discovery he achieves, he cannot keep from expressly raising the possibility to his friends of extending his thoughts out over the whole of nature. In 1786, he writes to Frau von Stein that he wants to extend his ideas—about the way nature brings forth its manifold life by playing, as it were, with one main form—“out over all the realms of nature, out over its whole realm.” And when in Italy the idea of metamorphosis in the plants stands plastically in all its details before his spirit, he writes in Naples on May 17, 1787: “The same law can be applied ... to everything living.” The first essay in Morphological Notebooks (1817)25“Morphologische Hefte” contains the words: “May that, therefore, which I often dreamed of in my youthful spirit as a book now appear as a sketch, even as a fragmentary collection.” It is a great pity that such a work from Goethe's hand did not come about. To judge by everything we have, it would have been a creation far surpassing everything of this sort that has been done in recent times. It would have become a canon from which every endeavor in the field of natural science would have to take its start and against which one could test the spiritual content of such an endeavor. The deepest philosophical spirit, which only superficiality could deny to Goethe, would have united with a loving immersion of oneself into what is given to sense experience; far from any one-sided desire to found a system purporting to encompass all beings in one general schema, this endeavor would grant every single individual its rightful due. We would have had to do here with the work of a spirit in whom no one individual branch of human endeavor pushes itself forward at the expense of all the others, but rather in whom the totality of human existence always hovers in the background when he is dealing with one particular area. Through this, every single activity receives its rightful place in the interrelationships of the whole. The objective immersing of oneself into the observed objects brings it about that the human spirit fully merges with them, so that Goethe's theories appear to us, not as though a human spirit abstracted them from the objects, but rather as though the objects themselves formed these theories within a human spirit who, in beholding, forgets himself. This strictest objectivity would make Goethe's work the most perfect work of natural science; it would be an ideal for which every natural scientist would have to strive; for the philosopher, it would be an archetypal model of how to find the laws of objective contemplation of the world. One can conclude that the epistemology now arising everywhere as a philosophical basic science will be able to become fruitful only when it takes as its starting point Goethe's way of thinking and of looking at the world. In the Annals of 1790, Goethe himself gives the reason why this work did not come about: “The task was so great that it could not be accomplished in a scattered life.”

[ 16 ] If one proceeds from this standpoint, the individual fragments we have of Goethe's natural science take on immense significance. We learn to value and understand them rightly, in fact, only when we regard them as going forth from that great whole.

[ 17 ] In the year 1784, however, merely as a kind of preliminary exercise, the treatise on the intermaxillary bone was to be produced. To begin with, it was not to be published, for Goethe writes of it to Sömmerring on March 6,1785: “Since my little treatise is not entitled at all to come before the public and is to be regarded merely as a rough draft, it would please me very much to hear anything you might want to share with me about this matter.” Nevertheless it was carried out with all possible care and with the help of all the necessary individual studies. At the same time, help was enlisted from young people who, under Goethe's guidance, had to carry out osteological drawings in accordance with Camper's methods. On April 23, 1784, therefore, he asks Merck for information about these methods and has Sömmerring send him Camperian drawings. Merck, Sömmerring, and other acquaintances are asked for skeletons and bones of every kind. On April 23, he writes to Merck that it would please him very much to have the following skeletons: “... a myrmecophaga, bradypus, lion, tiger, or similar skeletons.” On May 14, he asks Sömmerring for the skull of his elephant skeleton and of the hippopotamus, and on September 16, for the skulls of the following animals: “wildcat, lion, young bear, incognitum, anteater, camel, dromedary, sea lion.” Individual items of information are also requested from his friends: thus from Merck the description of the palatal part of his rhinoceros and particularly the explanation as to “how the rhinoceros horn is actually seated upon the nasal bone.” At this time, Goethe is utterly absorbed in his studies. The elephant skull mentioned above was sketched by Waitz from many sides by Camper's methods, and was compared by Goethe with a large skull in his possession and with other animal skulls, since he discovered that in this skull most of the sutures were not yet grown together. In connection with this skull, he makes an important observation. Until then one assumed that in all animals merely the incisors were embedded in the intermaxillary bone, and that the canine teeth belonged to the upper jaw bone; only the elephant was supposed to be an exception. In it, the canine teeth were supposed to be contained in the intermaxillary bone. This skull now shows him also that this is not the case, as he states in a letter to Herder. His osteological studies accompany him on a journey to Eisenach and to Braunschweig that Goethe undertakes during that summer. On the second trip, in Braunschweig, he wants “to look into the mouth of an unborn elephant and to carry on a hearty conversation with Zimmermann.” He writes further about this fetus to Merck: “I wish we had in our cupboard the fetus they have in Braunschweig: it would be quickly dissected, skeletized, and prepared. I don't know what value such a monster in spirits has if it is not dismembered and its inner structure explained.” From these studies, there then emerges that treatise which is reported in Volume I of the natural-scientific writings in Kürschner's National Literature. Loder was very helpful to Goethe in composing this treatise. With his assistance, a Latin terminology comes into being. Moreover, Loder prepares a Latin translation. In November 1784, Goethe sends the treatise to Knebel and already on December 19 to Merck, although only shortly before (on December 2) he believes that not much will come of it before the end of the year. The work was equipped with the necessary drawings. For Camper's sake, the Latin translation just mentioned was included. Merck was supposed to send the work on to Sömmerring. The latter received it in January 1785. From there it went to Camper. When we now take a look at the way Goethe's treatise was received, we are confronted by a quite unpleasant picture. At first no one has the organ to understand him except Loder, with whom he had worked, and Herder. Merck is pleased by the treatise, but is not convinced of the truth of what is asserted there. In the letter in which Sömmerring informs Merck of the arrival of the treatise, we read: “Blumenbach already had the main idea. In the paragraph which begins ‘Thus there can be no doubt,’ he [Goethe] says ‘since the rest of them (the edges) are grown together’; the only trouble is that these edges were never there. I have in front of me now jawbones of embryos, ranging from three months of age to maturity, and no edge was ever to be seen toward the front. And to explain the matter by the pressure of bones against each other? Yes, if nature works like a carpenter with hammer and wedges!” On February 13, 1785, Goethe writes to Merck: “I have received from Sömmerring a very frivolous letter. He actually wants to talk me out of it. Oh my!”—And Sömmerring writes to Merck on May 11, 1785: “Goethe, as I can see from his letter yesterday, still does not want to abandon his idea about the ossis intermaxillaris.”

[ 18 ] And now Camper.26Until now, one has assumed that Camper received the treatise anonymously. It came to him in a roundabout way: Goethe sent it first to Sömmerring, who sent it to Merck, who was supposed to get it to Camper. But among the letters of Merck to Camper (which are not yet published, and whose originals are to be found in the Library of the Netherlands Society for the Progress of Medicine in Amsterdam), there is one letter of January 17, 1785 containing the following passage (I quote it verbatim): “Mr. Goethe, celebrated poet, intimate counselor of the Duke of Weimar, has just sent me an osteological specimen that is supposed to be sent to you after Mr. Sömmerring has seen it ... It is a small treatise on the intermaxillary bone that teaches, us among other things, the truth that the manatee has four incisors and that the camel has two of them.” A letter of March 10, 1785, in which the name Goethe is again expressly present, states that Merck will shortly send the treatise on to Camper: “I will have the honor of sending you the osteological specimen of Mr. von Goethe, my friend ...” On April 28, 1785, Merck expressed the hope that Camper received the thing and again the name “Goethe” is present. Thus there is no doubt that Camper knew who the author was. On September 17, 1785, he communicates to Merck that the accompanying tables were not drawn at all according to his methods. He in fact found them to be quite faulty. The outer aspect of the beautiful manuscript is praised and the Latin translation is criticized—in fact, the advice is even given to the author that he brush up on his Latin. Three days later, he writes that he has made a number of observations about the intermaxillary bone, but that he must continue to maintain that man has no intermaxillary bone. He agrees with all of Goethe's observations except the ones pertaining to man. On March 21, 1786, he writes yet again that, out of a great number of observations, he has come to the conclusion: the intermaxillary bone does not exist in man. Camper's letters show clearly that he could go into the matter with the best possible will, but was not able to understand Goethe at all.

[ 19 ] Loder at once saw Goethe's discovery in the right light. He gives it a prominent place in his anatomical handbook of 1788 and treats it from now on in all his writings as a fully valid fact of science about which there cannot be the least doubt.

[ 20 ] Herder writes about this to Knebel: “Goethe has presented me with his treatise on the bone; it is very simple and beautiful; the human being travels the true path of nature and fortune comes to meet him.” Herder was in fact able to look at the matter with the “spiritual eye” with which Goethe saw it. Without this eye, a person could do nothing with this matter. One can see this best from the following. Wilhelm Josephi (instructor at the University of Göttingen) writes in his Anatomy of the Mammals27Anatomie der Säugetiere in 1787: “The ossa intermaxillaria is also considered to be one of the main characteristics differentiating the apes from man; yet, according to my observation, the human being also has such as ossa intermaxillaria, at least in the first months of his life, but it has usually grown together very early—already in the mother's womb, in fact—with the true upper jaw bones, especially in its external appearance, so that often no noticeable trace remains of it at all.” Goethe's discovery is, to be sure, also fully stated here, not as one demanded by the consistent realization of the typus, however, but rather as the expression of fact directly visible to the eye. If one relies only upon the latter, then, to be sure, it depends only upon a happy chance whether or not one finds precisely such specimens in which one can see the matter exactly. But if one grasps the matter in Goethe's ideal way, then these particular specimens serve merely as confirmation of the thought, are there merely to demonstrate openly what nature otherwise conceals; but the idea itself can be found in any specimen at all; every specimen reveals a particular case of the idea. In fact, if one possesses the idea, one is able through it to find precisely those cases in which the idea particularly expresses itself. Without the idea, however, one is at the mercy of chance. One sees, in actuality, that after Goethe had given the impetus by his great thought, one then gradually became convinced of the truth of his discovery through observation of numerous cases.

[ 21 ] Merck, to be sure, continued to vacillate. On February 13, 1785, Goethe sends him a split-open upper jawbone of a human being and one of a manatee, and gives him points of reference for understanding the matter. From Goethe's letter of April 8, it appears that Merck was won over to a certain extent. But he soon changed his mind again, for on November 11, 1786, he writes to Sömmerring: “According to what I hear, Vicq d'Azyr has actually included Goethe's so-called discovery in his book.”

[ 22 ] Sömmerring gradually abandoned his opposition. In his book On The Structure of the Human Body 28Vom Baue des menschlichen Körpers he says: “Goethe's ingenious attempt in 1785, out of comparative osteology, to show, with quite correct drawings, that man has the intermaxillary bone of the upper jaw in common with the other animals, deserved to be publicly recognized.”

[ 23 ] To be sure, it was more difficult to win over Blumenbach. In his Handbook of Comparative Anatomy 29Handbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie in 1805, he still stated the opinion that man has no intermaxillary bone. In his essay Principles of Zoological Philosophy, written in 1830 – 32, however, Goethe can already speak of Blumenbach's conversion. After personal communication, he came over to Goethe's side. On December 15, 1825, in fact, he presents Goethe with a beautiful example that confirmed his discovery. A Hessian athlete sought help from Blumenbach's colleague Langenbeck for an “os intermaxillare that was prominent in a quite animal-like way.” We still have to speak of later adherents of Goethe's ideas. But it should still be mentioned here that M.J. Weber succeeded, with diluted nitric acid, in separating from an upper jawbone an intermaxillary bone that had already grown into it.

[ 24 ] Goethe continued his study of bones even after completion of this treatise. The discoveries he was making at the same time in botany enliven his interest in nature even more. He is continually borrowing relevant objects from his friends. On December 7, 1785, Sömmerring is actually annoyed “that Goethe is not sending him back his heads.” From a letter of Goethe's to Sömmerring on June 8,1786 we learn that he still even then had skulls of his.

[ 25 ] In Italy also, his great ideas accompanied him. As the thought of the archetypal plant took shape in his spirit, he also arrives at concepts about man's form. On January 20, 1787, Goethe writes in Rome: “I am somewhat prepared for anatomy and have acquired, though not without effort, a certain level of knowledge of the human body. Here, through endless contemplation of statues, one's attention is continuously drawn to the human body, but in a higher way. The purpose of our medical and surgical anatomy is merely to know the part, and for this a stunted muscle will also serve. But in Rome, the parts mean nothing unless at the same time they present a noble and beautiful form.

[ 26 ] In the big hospital of San Spirito, they have set up for artists a very beautifully muscled body in such a way that the beauty of it makes one marvel. It could really be taken for a flayed demigod, a Marsyas.

[ 27 ] It is also the custom here, following the ancients, to study the skeleton not as an artificially arranged mass of bones but rather with the ligaments still attached, from which it receives some life and movement.”

[ 28 ] The main thing for Goethe here is to learn to know the laws by which nature forms organic shapes—and especially human ones—and to learn to know the tendency nature follows in forming them. On the one hand, Goethe is seeking within the series of endless plant shapes the archetypal plant with which one can endlessly invent more plants that must be consistent, i.e., that are fully in accordance with that tendency in nature and that would exist if suitable conditions were present; and on the other hand, Goethe was intent, with respect to the animals and man, upon “discovering the ideal characteristics” that are totally in accord with the laws of nature. Soon after his return from Italy, we hear that Goethe is “industriously occupied with anatomy,” and in 1789, he writes to Herder: “I have a newly discovered harmonium naturae to expound.” What is here described as newly discovered may be a part of his vertebral theory about the skull. The completion of this discovery, however, falls in the year 1790. What he knew up until then was that all the bones that form the back of the head represent three modified spinal vertebrae. Goethe conceived the matter in the following way. The brain represents merely a spinal cord mass raised to its highest level of perfection. Whereas in the spinal cord those nerves end and begin that serve primarily the lower organic functions, in the brain those nerves begin and end that serve higher (spiritual) functions, pre-eminently the sense nerves. In the brain there only appears in a developed form what already lies indicated in the spinal cord as possibility. The brain is a fully developed spinal cord; the spinal cord a brain that has not yet fully unfolded. Now the vertebrae of the spinal column are perfectly shaped in conformity with the parts of the spinal cord; the vertebrae are the organs needed to enclose them. Now it seems probable in the highest degree, that if the brain is a spinal cord raised to its highest potentiality, then the bones enclosing it are also only more highly developed vertebrae. The whole head appears in this way to be prefigured in the bodily organs that stand at a lower level. The forces that are already active on lower levels are at work here also, but in the head they develop to the highest potentiality lying within them. Again, Goethe's concern is only to find evidence as to how the matter actually takes shape in accordance with sense-perceptible reality. Goethe says that he recognized this relationship very soon with respect to the bone of the back of the head, the occiput, and to the posterior and anterior sphenoid bones; but that—during his trip to northern Italy when he found a cracked-open sheep's skull on the dunes of the Lido—he recognized that the palatal bone, the upper jaw, and the intermaxillary bone are also modified vertebrae. This skull had fallen apart so felicitously that the individual vertebrae were distinctly recognizable in the individual parts. Goethe's showed this beautiful discovery to Frau von Kalb on April 30, 1790 with the words: “Tell Herder that I have gotten one whole principle nearer to animal form and to its manifold transformations, and did so through the most remarkable accident.”

[ 29 ] This was a discovery of the most far-reaching significance. It showed that all the parts of an organic whole are identical with respect to idea, that “inwardly unformed” organic masses open themselves up outwardly in different ways, and that it is one and the same thing that—at a lower level as spinal cord nerve and on a higher level as sense nerve—opens itself up into the sense organ, that takes up, grasps, and apprehends the outer world. This discovery revealed every living thing in its power to form and give shape to itself from within outward; only then was it grasped as something truly living. Goethe's basic ideas, also in relation to animal development, had now attained their final form. The time had come to present these ideas in detail, although he had already planned to do this earlier, as Goethe's correspondence with F.H. Jacobi shows us. When he accompanied the Duke, in July 1790, to the Schlesian encampment, he occupied himself primarily there (in Breslau) with his studies on animal development. He also began there really to write down his thoughts on this subject. On August 31, 179(), he writes to Friedrich von Stein: “In all this bustle, I have begun to write my treatise on the development of the animals.”

[ 30 ] In a comprehensive sense, the idea of the animal typus is contained in the poem “Metamorphosis of the Animals,” which first appeared in 1820 in the second of the morphological notebooks. During the years 1790–95, Goethe's primary natural-scientific work was with his colour theory. At the beginning of 1795, Goethe was in Jena, where the brothers von Humboldt, Max Jacobi, and Schiller were also present. In this company, Goethe brought forward his ideas about comparative anatomy. His friends found his presentations so significant that they urged him to put his ideas down on paper. It is evident from a letter of Goethe to the elder Jacobi that Goethe complied with this urging right away, while still in Jena, by dictating to Max Jacobi the outline of a comparative osteology which is printed in the first volume of Goethe's natural-scientific writings in Kürschner's National Literature. In 1796, the introductory chapters were further elaborated.

These treatises contain Goethe's basic views about animal development, just as his writing, “An Attempt to Explain the Metamorphosis of the Plant,” 30“Versuch, die Metamorphose der Pflanze zu erklären” contains his basic views on plant development. Through communication with Schiller—since 1794 Goethe came to a turning point in his views, in that from now on, with respect to his own way of proceeding and of doing research, he began to observe himself, so that his way of viewing things became for him an object of study. After these historical reflections, let us now turn to the nature and significance of Goethe's views on the development of organisms.

3. Die Entstehung von Goethes Gedanken über die Bildung der Tiere

[ 1 ] Lavaters großes Werk: «Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe» erschien in den Jahren 1775-1778. Goethe hatte daran regen Anteil genommen, nicht nur dadurch, daß er die Herausgabe leitete, sondern indem er auch selbst Beiträge lieferte. Besonders interessant ist es nun aber, daß wir in diesen Beiträgen schon den Keim zu seinen späteren zoologischen Arbeiten finden können.

[ 2 ] Die Physiognomik suchte in der äußeren Form des Menschen dessen Inneres, dessen Geist zu erkennen. Man behandelte die Gestalt nicht um ihrer selbst willen, sondern als Ausdruck der Seele. Goethes plastischer, zur Erkenntnis äußerer Verhältnisse geschaffener Geist blieb dabei nicht stehen. Mitten in jenen Arbeiten, welche die äußere Form nur als Mittel zur Erkenntnis des Inneren behandelten, ging ihm die Bedeutung der ersteren, der Gestalt, in ihrer Selbständigkeit auf. Wir sehen dieses aus seinen Arbeiten über die Tierschädel aus dem Jahre 1776, welche sich im 2. Bande, 2. Abschnitt der «Physiognomischen Fragmente» eingeschaltet finden. 25gl. Natw. Schr., 2. Bd., S. 68ff. Er liest in diesem Jahre Aristoteles über die Physiognomik, 26Brief an J. K. Lavater, etwa 20.März 1776; WA 3, 42. findet sich dadurch zu obigen Arbeiten angeregt, zugleich aber versucht er es, den Unterschied des Menschen von den Tieren zu untersuchen. Er findet diesen Unterschied in dem durch das Ganze des menschlichen Baues bedingten Hervortreten des Hauptes, in der hohen Ausbildung des menschlichen Gehirnes, zu dem alle Teile des Körpers als zu ihrer Zentralstätte hinweisen. «Wie die ganze Gestalt als Grundpfeiler des Gewölbes dasteht, in dem sich der Himmel bespiegeln soll.» 27Vgl. Natw. Schr., 2. Bd., S. 69 [Eingang]. Das Gegenteil davon findet er nun beim tierischen Baue. «Der Kopf an das Rückgrat nur angehängt! Das Gehirn, Ende des Rückenmarks, hat nicht mehr Umfang, als zur Auswirkung der Lebensgeister und zu Leitung eines ganz gegenwärtig sinnlichen Geschöpfes nötig ist.» 28Ebenda. Mit diesen Andeutungen hat sich Goethe über die Betrachtung einzelner Zusammenhänge des Äußeren mit dem Inneren des Menschen erhoben zur Auffassung eines großen Ganzen und zur Anschauung der Gestalt als solcher. Er ist zur Ansicht gekommen, daß das Ganze des menschlichen Baues die Grundlage bildet zu seinen höheren Lebensäußerungen, daß in der Eigentümlichkeit dieses Ganzen die Bedingung liegt, welche den Menschen an die Spitze der Schöpfung stellt. Was wir uns dabei vor allem gegenwärtig halten müssen, ist, daß Goethe die tierische Gestalt in der ausgebildeten menschlichen wieder aufsucht; nur daß dort die mehr den animalischen Verrichtungen dienenden Organe in den Vordergrund treten, gleichsam der Punkt sind, auf den die ganze Bildung hindeutet und dem sie dient, während die menschliche Bildung jene Organe besonders ausbildet, welche den geistigen Funktionen dienen. Schon hier finden wir: Was Goethe als tierischer Organismus vorschwebt, ist nicht mehr dieser oder jener sinnlichwirkliche, sondern ein ideeller, der sich bei den Tieren mehr nach einer niederen, bei dem Menschen nach einer höheren Seite ausbildet. Schon hier liegt der Keim zu dem, was Goethe später Typus nannte und womit er «kein einzelnes Tier», sondern die «Idee» des Tieres bezeichnen wollte. Ja noch mehr: Schon hier findet man einen Anklang an ein später von ihm ausgesprochenes, in seinen Konsequenzen wichtiges Gesetz, daß nämlich «die Mannigfaltigkeit der Gestalt daher entspringt, daß diesem oder jenem Teil ein Übergewicht über die andern zugestanden ist.» 29Siehe Natw. Schr., 1. Bd., S. 247. Es wird ja schon hier der Gegensatz von Tier und Mensch darinnen gesucht, daß sich eine ideelle Gestalt nach zwei verschiedenen Richtungen hin ausbildet, daß jedesmal ein Organsystem das Übergewicht gewinnt und das ganze Geschöpf davon seinen Charakter erhält.

[ 3 ] In demselben Jahre (1776) finden wir aber auch, daß Goethe Klarheit darüber gewinnt, wovon auszugehen ist, wenn man die Gestalt des tierischen Organismus betrachten will. Er erkannte, daß die Knochen die Grundfesten der Bildung sind, 30Siehe Natw. Schr., 2. Bd. [S. 68 f.]. ein Gedanke, den er später aufrechterhalten hat, indem er bei den anatomischen Arbeiten durchaus von der Knochenlehre ausging. In diesem Jahre schreibt er den in dieser Hinsicht wichtigen Satz nieder: 31Ebenda [S. 69]. «Die beweglichen Teile formen sich nach ihnen (den Knochen), eigentlicher zu sagen, mit ihnen und treiben ihr Spiel nur insoweit es die festen vergönnen.» Auch eine weitere Andeutung in Lavaters Physiognomik: «Man kann es schon bemerkt haben, daß ich das Knochensystem für die Grundzeichnung des Menschen - den Schädel für das Fundament des Knochensystems und alles Fleisch beinahe nur für das Kolorit dieser Zeichnung halte», 32Lavaters Fragmente II, 143. mag wohl auf Goethes Anregung, der sich mit Lavater oft über diese Dinge besprach, geschrieben worden sein. Sie sind ja mit den von Goethe verfaßten Andeutungen 33Siehe Natw. Schr., 2. Bd. [S. 69]. identisch. Nun macht aber Goethe eine weitere Bemerkung dazu, welche wir besonders berücksichtigen müssen: «Diese Anmerkung (daß man an den Knochen und namentlich am Schädel am stärksten sehen kann, wie die Knochen die Grundfesten der Bildung sind), die hier (bei Tieren) unleugbar ist, wird bei der Anwendung auf die Verschiedenheit der Menschenschädel großen Widerspruch zu leiden haben.» 34Ebenda. Was tut Goethe hier anderes, als das einfachere Tier im zusammengesetzten Menschen wieder aufsuchen, wie er sich später (1795) ausdrückt! Wir gewinnen hieraus die Überzeugung, daß die Grundgedanken, auf welchen später Goethes Gedanken über die Bildung der Tiere aufgebaut werden sollten, aus der Beschäftigung mit Lavaters Physiognomik heraus im Jahre 1776 sich bei ihm festsetzten.

[ 4 ] In diesem Jahre beginnt auch Goethes Studium des Einzelnen der Anatomie. Am 22. Januar 1776 schreibt er an Lavater: «Der Herzog hat mir sechs Schädel kommen lassen, habe herrliche Bemerkungen gemacht, die Euer Hochwürden zu Diensten stehen, wenn dieselben Sie nicht ohne mich fanden.» [WA 3, 20] Die weiteren Anregungen zu einem eingehenderen Studium der Anatomie boten ihm die Beziehungen zur Universität Jena. Wir haben die ersten Andeutungen hierüber aus dem Jahre 1781. In dem von Keil herausgegebenen Tagebuche bemerkt er unter dem 15. Oktober 1781, daß er nach Jena mit dem alten Einsiedel ging und dort Anatomie trieb. Hier war ein Gelehrter, der Goethes Studien ungeheuer förderte: Loder. Derselbe führt ihn denn auch weiter in die Anatomie ein, wie er am 29. Oktober 1781 an Frau von Stein 35«Ein beschwerlicher Liebesdienst, den ich übernommen habe, führt mich meiner Liebhaberei näher. Loder erklärt mir alle Beine und Muskeln, und ich werde in wenig Tagen vieles fassen.» [WA 5, 207] und am 4. November an Karl August 36«Mir hat er (Loder) in diesen acht Tagen, die wir, freilich soviel als meine Wächterschaft litt, fast ganz dazu anwandten, Osteologie und Myologie durchdemonstriert.« [WA 5, 211] schreibt. In letzterem Briefe spricht er nun auch die Absicht aus, den «jungen Leuten» der Zeichenakademie «das Skelett zu erklären und sie zur Kenntnis des menschlichen Körpers anzuführen». Er setzt hinzu: «Ich tue es zugleich um meinet- und ihretwillen, die Methode, die ich gewählt habe, wird sie diesen Winter über völlig mit den Grundsäulen des Körpers bekannt machen.» Die Einzeichnungen im Tagebuch Goethes zeigen, daß er diese Vorlesungen wirklich gehalten und am 16. Januar beendet hat. Gleichzeitig wird wohl viel mit Loder über den Bau des menschlichen Körpers verhandelt worden sein. Unter dem 6. Januar bemerkt das Tagebuch: Demonstration des Herzens durch Loder. Haben wir nun gesehen, daß Goethe schon 1776 weitausblickende Gedanken über den Bau der tierischen Organisation hegte, so ist keinen Augenblick daran zu zweifeln, daß seine jetzigen eingehenden Beschäftigungen mit Anatomie über die Betrachtung der Einzelheiten hinaus sich zu höheren Gesichtspunkten erhoben. So schreibt er an Lavater und Merck am 14. November 1781, er behandele «die Knochen als einen Text, woran sich alles Leben und alles Menschliche anhängen läßt». [WA 5, 217 u. 220] Bei Betrachtung eines Textes bilden sich in unserem Geiste Bilder und Ideen, die von jenem hervorgerufen, erzeugt erscheinen. Als einen solchen Text behandelte Goethe die Knochen, d. h. indem er sie betrachtet, gehen ihm Gedanken über alles Leben und alles Menschliche auf. Es mußten sich bei ihm also bei diesen Betrachtungen bestimmte Ideen über die Bildung des Organismus geltend gemacht haben. Nun haben wir aus dem Jahre 1782 eine Ode von Goethe: «Das Göttliche», welche uns einigermaßen erkennen läßt, wie er über die Beziehung des Menschen zur übrigen Natur damals dachte. Die erste Strophe heißt:

«Edel sei der Mensch,

Hilfreich und gut! Denn das allein

Unterscheidet ihn

Von allen Wesen, Die wir kennen.»

[ 5 ] Indem in den ersten zwei Zeilen dieser Strophe der Mensch nach seinen geistigen Eigenschaften erfaßt wird, sagt Goethe, diese allein unterscheiden ihn von allen anderen Wesen der Welt. Dieses «allein» zeigt uns ganz klar, daß Goethe den Menschen seiner physischen Konstitution nach durchaus in Übereinstimmung mit der übrigen Natur auffaßte. Es wird bei ihm der Gedanke, auf den wir schon oben aufmerksam machten, immer lebendiger, daß eine Grundform die Gestalt des Menschen sowohl wie der Tiere beherrsche, daß sie bei ersterem sich nur zu einer solchen Vollkommenheit steigere, daß sie fähig ist, der Träger eines freien geistigen Wesens zu sein. Seinen sinnenfälligen Eigenschaften nach muß auch der Mensch, wie es in jener Ode weiter heißt:

«Nach ewigen, ehrnen

Großen Gesetzen»

Seines ... «Daseins

Kreise vollenden.»

[ 6 ] Aber diese Gesetze bilden sich bei ihm nach einer Seite aus, die es ihm möglich macht, daß er das «Unmögliche» vermag:

«Er unterscheidet,

Wählet und richtet;

Er kann dem Augenblick

Dauer verleihen.»

[ 7 ] Nun muß man dazu noch bedenken, daß, während sich diese Anschauungen bei Goethe immer bestimmter ausbildeten, er in lebendigem Verkehre mit Herder stand, der im Jahre 1783 seine «Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit» aufzuzeichnen begann. Dieses Werk ging beinahe hervor aus den Unterhaltungen der beiden, und manche Idee wird wohl auf Goethe zurückzuführen sein. Die Gedanken, welche hier ausgesprochen werden, sind oft ganz Goethisch, nur in Herders Weise gesagt, so daß wir aus denselben einen sicheren Schluß auf die damaligen Gedanken Goethes machen können.

[ 8 ] Herder hat nun im ersten Teil 37Herder, Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit, 1. Teil, 5. Buch, in: Herders Sämtliche Werke, hg. v. B. Suphan; Berlin 1877-1913, 13. Bd., S. 167. von dem Wesen der Welt folgende Auffassung. Es muß eine Hauptform vorausgesetzt werden, welche durch alle Wesen hindurchgeht und sich in verschiedener Weise verwirklicht. «Vom Stein zum Kristall, vom Kristall zu den Metallen, von diesen zur Pflanzenschöpfung, von den Pflanzen zum Tier, von diesem zum Menschen sahen wir die Form der Organisation steigen, mit ihr auch die Kräfte und Triebe des Geschöpfs vielartiger werden, und sich endlich alle in der Gestalt des Menschen, sofern diese sie fassen konnte, vereinen.» Der Gedanke ist ganz klar: Eine ideelle, typische Form, die als solche selbst nicht sinnenfällig wirklich ist, realisiert sich in einer unendlichen Menge räumlich voneinander getrennter und ihren Eigenschaften nach verschiedenen Wesen bis herauf zum Menschen. Auf den niederen Stufen der Organisation verwirklicht sie sich stets nach einer bestimmten Richtung; nach dieser bildet sie sich besonders aus. Indem diese typische Form bis zum Menschen heransteigt, nimmt sie alle Bildungsprinzipien, die sie bei den niederen Organismen immer nur einseitig ausgebildet hat, die sie auf verschiedene Wesen verteilt hat, zusammen, um eine Gestalt zu bilden. Daraus geht auch die Möglichkeit einer so hohen Vollkommenheit beim Menschen hervor. Bei ihm hat die Natur auf ein Wesen verwendet, was sie bei den Tieren auf viele Klassen und Qrdnungen zerstreut hat. Dieser Gedanke wirkte ungemein fruchtbar auf die nachherige deutsche Philosophie. Es sei hier die Darstellung, welche Oken später für dieselbe Vorstellung gegeben hat, zu ihrer Verdeutlichung erwähnt. Er sagt: 38Oken, Lehrbuch der Naturphilosophie. 2. Aufl., Jena 1831,S. 389. «Das Tierreich ist nur ein Tier, d. h. die Darstellung der Tierheit mit allen ihren Organen jedes für sich ein Ganzes. Ein einzelnes Tier entsteht, wenn ein einzelnes Organ sich vom allgemeinen Tierleib ablöst und dennoch die wesentlichen Tierverrichtungen ausübt. Das Tierreich ist nur das zerstückelte höchste Tier: Mensch. Es gibt nur eine Menschenzunft, nur ein Menschengeschlecht, nur eine Menschengattung, eben weil er das ganze Tierreich ist.» So gibt es z. B. Tiere, bei denen die Tastorgane ausgebildet sind, ja die ganze Organisation auf die Tätigkeit des Tastens hinweist und in ihr das Ziel findet, andere, bei denen besonders die Freßwerkzeuge ausgebildet sind usf., kurz bei jeder Tiergattung tritt einseitig ein Organsystem in den Vordergrund; das ganze Tier geht in demselben auf; alles übrige tritt bei ihm in den Hintergrund. In der menschlichen Bildung nun bilden sich alle Organe und Organsysteme so aus, daß eines dem andern Raum genug zur freien Entwicklung läßt, daß jedes einzelne in jene Schranken zurücktritt, welche nötig erscheinen, um alle andern in gleicher Weise zur Geltung kommen zu lassen. So entsteht ein harmonisches Ineinanderwirken der einzelnen Organe und Systeme zu einer Harmonie, welche den Menschen zum vollkommensten, die Vollkommenheiten aller übrigen Geschöpfe in sich vereinigenden Wesen macht. Diese Gedanken haben nun auch den Inhalt der Gespräche Goethes mit Herder gebildet, und Herder verleiht ihnen in folgender Weise Ausdruck: daß «das Menschengeschlecht als der große Zusammenfluß niederer organischer Kräfte» anzusehen ist, «die in ihm zur Bildung der Humanität kommen sollten». Und an einem anderen Orte: «Und so können wir annehmen: daß der Mensch ein Mittelgeschöpf unter den Tieren, d. i. die ausgearbeitete Form sei, in der sich die Züge aller Gattungen um ihn her im feinsten Inbegriff sammeln.» 39Herder, a. a. 0. 1. Teil, 5. Buch, bzw. I. Teil, 2. Buch.

[ 9 ] Um den Anteil, welchen Goethe an Herders Werke «Ideen zu einer Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit» nahm, zu kennzeichnen, wollen wir folgende Stelle aus einem Briefe Goethes an Knebel vom 8. Dezember 1783 anführen: «Herder schreibt eine Philosophie der Geschichte, wie Du Dir denken kannst, von Grund aus neu. Die ersten Kapitel haben wir vorgestern zusammen gelesen, sie sind köstlich ... Welt- und Naturgeschichte rast jetzt recht bei uns.» [WA 6, 224] Die Ausführungen Herders im 3. Buch VI und im 4. Buch 1, daß die in der menschlichen Organisation bedingte aufrechte Haltung und was damit zusammenhängt, die Grundbedingung seiner Vernunfttätigkeit ist, erinnert direkt an das, was Goethe 1776 im 2. Abschnitt des zweiten Bandes der «Physiognomischen Fragmente» Lavaters über den Geschlechtsunterschied des Menschen von den Tieren angedeutet hat, und was wir schon oben erwähnt haben. Es ist nur eine Ausführung jenes Gedankens. Das alles berechtigt uns aber anzunehmen, daß Goethe und Herder in bezug auf ihre Ansichten über die Stellung des Menschen in der Natur in jener Zeit (1783ff.) der Hauptsache nach einig waren.

[ 10 ] Nun bedingt eine solche Grundanschauung aber, daß jedes Organ, jeder Teil eines Tieres sich im Menschen müsse wiederfinden lassen, nur in die durch die Harmonie des Ganzen bedingten Schranken zurückgedrängt. Ein Knochen z. B. muß allerdings bei einer bestimmten Tiergattung zu seiner besonderen Ausbildung kommen, muß sich hier vordrängen, allein er muß sich bei allen übrigen auch wenigstens angedeutet finden, ja er darf beim Menschen nicht fehlen. Nimmt er dort jene Gestalt an, welche ihm vermöge seiner eigenen Gesetze zukommt, so hat er sich hier einem Ganzen zu fügen, seine eigenen Bildungsgesetze denen des ganzen Organismus anzupassen. Fehlen aber darf er nicht, wenn nicht in der Natur ein Riß geschehen soll, wodurch die konsequente Ausgestaltung eines Typus gestört würde.

[ 11 ] So stand es mit den Anschauungen bei Goethe, als er auf einmal eine Ansicht gewahr wurde, welche diesen großen Gedanken durchaus widersprach. Den Gelehrten der damaligen Zeit war es vornehmlich darum zu tun, Kennzeichen zu finden, welche eine Tiergattung von der andern unterscheiden. Der Unterschied der Tiere von dem Menschen sollte darin bestehen, daß die ersteren zwischen den beiden symmetrischen Hälften des Oberkiefers einen kleinen Knochen, den Zwischenknochen haben, der die oberen Schneidezähne enthält, und welcher dem Menschen fehlen soll. Als Merck im Jahre 1782 anfing, sich lebhaft für die Knochenlehre zu interessieren und sich um Beihilfe an einige der bekanntesten Gelehrten damaliger Zeit wandte, erhielt er von einem derselben, dem bedeutenden Anatomen Sömmerring, am 8. Oktober 1782 folgende Auskunft über den Unterschied von Tier und Mensch: 40Briefe an J. H. Merck, Darmstadt 1835 [S. 354 f.]. «Ich wünschte, daß Sie Blumenbach nachsähen, wegen des ossis intermaxillaris, der ceteris paribus der einzige Knochen ist, den alle Tiere vom Affen an, selbst der Orang Utang eingeschlossen, haben, der sich hingegen nie beim Menschen findet; wenn Sie diesen Knochen abrechnen, so fehlt Ihnen nichts, um nicht alles vom Menschen auf die Tiere transferieren zu können. Ich lege deshalb einen Kopf von einer Hirschkuh bei, um Sie zu überzeugen, daß dieses os intermaxillare (wie es Blumenbach) oder os incisivum (wie es Camper nennt) selbst bei Tieren vorhanden ist, die keine Schneidezähne in der obern Kinnlade haben.» Obwohl Blumenbach an den Schädeln ungeborener oder junger Kinder eine Spur quasi rudimentum des ossis intermaxillaris fand, ja sogar an einem solchen Schädel einmal zwei völlig abgesonderte kleine Knochenkerne als wahren Zwischenknochen fand, so gab er die Existenz eines solchen doch nicht zu. Er sagt davon: «Es ist noch himmelweit vom wahren osse intermaxillari verschieden.» Camper, der berühmteste Anatom der Zeit, war derselben Ansicht. Der letztere sagt 41In: «Natuurkundige verhandelingen over den orang Outang.. .». Amsterdam 1782, p. 75, § 2. z. B. von den Zwischenknochen: «die nimmer by menschen gevonden wordt, zelfs niet by de Negers.» Merck war für Camper von der innigsten Verehrung durchdrungen und befaßte sich mit seinen Schriften.

[ 12 ] Nicht nur Merck, sondern auch Blumenbach und Sömmerring standen mit Goethe im Verkehre. Der Briefwechsel mit ersterem zeigt uns, daß Goethe an dessen Knochenuntersuchungen den innigsten Anteil nahm und über diese Dinge seine Gedanken mit ihm austauschte. Am 27. Oktober 1782 ersuchte er Merck, ihm etwas von Campers Inkognito zu schreiben und ihm dessen Briefe zu schicken. 42[WA 6,75] Ferner haben wir im April des Jahres 1783 einen Besuch Blumenbachs in Weimar zu verzeichnen. Im September desselben Jahres geht Goethe nach Göttingen, um dort Blumenbach und alle Professoren zu besuchen. Am 28. September schreibt er an Frau von Stein: «Ich habe mir vorgenommen alle Professoren zu besuchen und Du kannst denken, was das zu laufen gibt, um in ein paar Tagen herumzukommen.» [WA 6, 202] Er geht hierauf nach Kassel, wo er mit Forster und Sömmerring zusammentrifft. Von dort aus schreibt er an Frau von Stein am 2. Oktober: «Ich sehe sehr schöne und gute Sachen und werde für meinen stillen Fleiß belohnt. Das Glücklichste ist, daß ich nun sagen kann, ich bin auf dem rechten Wege und es geht mir von nun an nichts verloren.» [WA 6, 204]

[ 13 ] In diesem Verkehr wird Goethe wohl zuerst auf die herrschenden Ansichten über den Zwischenknochen aufmerksam geworden sein. Bei seinen Anschauungen mußten ihm diese sofort als ein Irrtum erscheinen. Die typische Grundform, nach welcher alle Organismen gebaut sein müssen, wäre damit vernichtet. Bei Goethe konnte kein Zweifel obwalten, daß auch dieses Glied, welches bei allen höheren Tieren mehr oder weniger ausgebildet zu finden ist, auch an der Bildung der menschlichen Gestalt teil haben müsse, und hier nur zurücktreten werde, weil die Organe der Nahrungsaufnahme überhaupt hinter denen, welche geistigen Funktionen dienen, zurücktreten. Goethe konnte vermöge seiner ganzen Geistesrichtung nicht anders denken, als daß ein Zwischenknochen auch beim Menschen vorhanden sei. Es handelte sich nur um den empirischen Nachweis desselben, nur darum, welche Gestalt er bei dem Menschen annimmt, inwiefern er sich in das Ganze des Organismus hier einfügt. Dieser Nachweis gelang ihm nun im Frühling des Jahres 1784 in Gemeinschaft mit Loder, mit dem er in Jena Menschen- und Tierschädel verglich. Goethe kündigte die Sache am 27. März sowohl der Frau von Stein 43«Es ist mir ein köstliches Vergnügen geworden, ich habe eine anatomische Entdeckung gemacht, die wichtig und schön ist.» [WA 6, 259] wie auch Herder an. 44«Ich habe gefunden - weder Gold noch Silber, aber was mir eine unsägliche Freude macht - das os intermaxillare am Menschen!» [WA 6, 258]

[ 14 ] Man darf nun diese einzelne Entdeckung gegenüber den großen Gedanken, von denen sie getragen ist, nicht überschätzen; sie hatte auch für Goethe nur den Wert, ein Vorurteil hinwegzuräumen, welches hinderlich erschien, wenn seine Ideen bis in die äußersten Kleinigkeiten eines Organismus konsequent verfolgt werden sollten. Als einzelne Entdeckung erblickte sie auch Goethe nie, immer nur im Zusammenhange mit seiner großen Naturanschauung. So haben wir es zu verstehen, wenn er in dem obenerwähnten Briefe an Herder sagt: «Es soll Dich auch recht herzlich freuen, denn es ist wie der Schlußstein zum Menschen, fehlt nicht, ist auch da! Aber wie!» Und gleich erinnert er den Freund an weitere Ausblicke: «ich habe mir's auch in Verbindung mit Deinem Ganzen gedacht, wie schön es da wird.» Die Behauptung: die Tiere haben einen Zwischenknochen, der Mensch aber keinen, konnte für Goethe keinen Sinn haben. Liegt es in den einen Organismus bildenden Kräften, bei den Tieren zwischen den beiden Oberkieferknochen einen Zwischenknochen einzuschieben, so müssen dieselben bei dem Menschen an jener Stelle, wo sich bei den Tieren jener Knochen befindet, in wesentlich derselben, nur der äußeren Erscheinung nach verschiedenen Weise tätig sein. Weil Goethe sich den Organismus nie als tote, starre Zusammensetzung, sondern immer als aus seinen inneren Bildungskräften hervorgehend dachte, so mußte er sich fragen: Was machen diese Kräfte im Oberkiefer des Menschen? Es konnte sich gar nicht darum handeln, ob der Zwischenknochen vorhanden, sondern wie er beschaffen ist, was für eine Bildung er annimmt. Und dieses mußte empirisch gefunden werden.

[ 15 ] Bei Goethe wurde nun der Gedanke immer reger, ein größeres Werk über die Natur auszuarbeiten. Wir können dies aus verschiedenen Äußerungen entnehmen. So schreibt er im November 1784 an Knebel, als er ihm die Abhandlung über seine Entdeckung überschickt: «Ich habe mich enthalten, das Resultat, worauf schon Herder in seinen Ideen deutet, schon jetzo merken zu lassen, daß man nämlich den Unterschied des Menschen vom Tier in nichts einzelnem finden könne.» [WA 6, 389] Hier ist vor allem wichtig, daß Goethe sagt, er habe sich enthalten, den Grundgedanken schon jetzo merken zu lassen; er will das also später in einem größeren Zusammenhange tun. Ferner zeigt uns diese Stelle, daß die Grundgedanken, die uns bei Goethe vor allem interessieren: die großen Ideen über den tierischen Typus längst vor jener Entdeckung vorhanden waren. Denn Goethe gesteht hier selbst, daß sie sich schon in Herders Ideen angedeutet finden; die Stellen aber, in denen dies geschieht, sind vor der Entdeckung des Zwischenknochens geschrieben. Die Entdeckung des Zwischenknochens ist somit nur eine Folge jener großen Anschauungen. Für jene, welche diese Anschauungen nicht hatten, mußte sie unverständlich bleiben. Es war ihnen das einzige naturhistorische Merkmal genommen, wodurch sie den Menschen von den Tieren schieden. Von jenen Gedanken, welche Goethe beherrschten und die wir früher andeuteten, daß die bei den Tieren zerstreuten Elemente sich in der einen menschlichen Gestalt zu einer Harmonie vereinigen und so trotz der Gleichheit alles Einzelnen eine Differenz im Ganzen begründen, welche dem Menschen seinen hohen Rang in der Reihe der Wesen anweist, davon hatten sie wenig Ahnung. Ihr Betrachten war kein ideelles, sondern ein äußerliches Vergleichen; und für das letztere war allerdings der Zwischenknochen beim Menschen nicht da. Was Goethe verlangte: mit den Augen des Geistes zu sehen, dafür hatten sie wenig Verständnis. Das begründete denn auch den Unterschied des Urteiles zwischen ihnen und Goethe. Während Blumenbach, der die Sache doch auch ganz deutlich sah, zu dem Schlusse kam: «Es ist doch himmelweit verschieden vom wahren osse intermaxillari», urteilt Goethe: Wie läßt sich eine noch so große äußere Verschiedenheit bei der notwendigen inneren Identität erklären. Goethe wollte nun offenbar diesen Gedanken konsequent ausarbeiten und er hat sich besonders in den nun folgenden Jahren viel damit beschäftigt. Am 1. Mai 1784 schreibt Frau von Stein an Knebel: 45Wir führten ihre Worte schon oben [S. 26] in anderem Zusammenhange an. «Herders neue Schrift macht wahrscheinlich, daß wir erst Pflanzen und Tiere waren ... Goethe grübelt jetzt gar denkreich in diesen Dingen und jedes, was erst durch seine Vorstellung gegangen ist, wird äußerst interessant.» In welchem Grade in Goethe der Gedanke lebte, seine Anschauungen über die Natur in ein einem größeren Werke darzustellen, das wird uns besonders anschaulich, wenn wir sehen, daß er bei jeder neuen Entdeckung, die ihm gelingt, nicht umhin kann, Freunden gegenüber die Möglichkeit einer Ausdehnung seiner Gedanken auf die ganze Natur ausdrücklich hervorzuheben. Im Jahre 1786 schreibt er an Frau von Stein, er wolle seine Ideen über die Weise, wie die Natur mit einer Hauptform gleichsam spielend das mannigfaltige Leben hervorbringt, «auf alle Reiche der Natur, auf ihr ganzes Reich» ausdehnen. Und da in Italien der Metamorphosengedanke für die Pflanze bis in alle Einzelheiten plastisch vor seinem Geiste steht, schreibt er in Neapel am 17. Mai 1787 nieder: «Dasselbe Gesetz wird sich auf alles ... Lebendige anwenden lassen.» 46Italienische Reise. Der erste Aufsatz der «Morphologischen Hefte» (1817) enthält die Worte: «Mag daher das, was ich mir in jugendlichem Mute öfters als ein Werk träumte, nun als Entwurf, ja als fragmentarische Sammlung hervortreten.» Daß ein solches Werk von Goethes Hand nicht zustande kam, müssen wir beklagen. Nach alledem, was vorliegt, wäre es eine Schöpfung geworden, welche alles, was von dergleichen in der neueren Zeit geleistet wurde, weit hinter sich gelassen hätte. Es wäre ein Kanon geworden, von dem jede Bestrebung auf naturwissenschaftlichem Gebiete ausgehen müßte und an dem man ihren geistigen Gehalt prüfen könnte. Der tiefste philosophische Geist, welchen nur Oberflächlichkeit Goethe absprechen kann, hätte sich hier verbunden mit einer liebevollen Versenkung in das sinnlicherfahrungsgemäß Gegebene; fern von jeder einseitigen Systemsucht, welche durch ein allgemeines Schema alle Wesen zu umfassen glaubt, würde hier jeder einzelnen Individualität ihr Recht widerfahren sein. Wir hätten es hier mit dem Werke eines Geistes zu tun, bei dem nicht ein einzelner Zweig menschlichen Strebens mit Zurücksetzung aller anderen sich hervortut, sondern bei dem die Totalität menschlichen Seins immer im Hintergrunde schwebt, wenn er ein einzelnes Gebiet behandelt. Dadurch bekommt jede einzelne Tätigkeit ihre gehörige Stelle im Zusammenhange des Ganzen. Die objektive Versenkung in die betrachteten Gegenstände verursacht, daß der Geist in ihnen völlig aufgeht, so daß uns Goethes Theorien so erscheinen, als ob sie nicht ein Geist von den Gegenständen abstrahierte, sondern als ob sie die Gegenstände selbst in einem Geiste bildeten, der sich bei der Betrachtung selbst vergißt. Diese strengste Objektivität würde Goethes Werk zum vollendetsten Werke der Naturwissenschaft machen; es wäre ein Ideal, dem jeder Naturforscher nachstreben müßte; es wäre für den Philosophen ein typisches Musterbild für die Auffindung der Gesetze objektiver Weltbetrachtung. Man kann annehmen, daß die Erkenntnistheorie, welche jetzt als eine philosophische Grundwissenschaft allerwärts auftritt, erst dann wird fruchtbar werden können, wenn sie ihren Ausgangspunkt von Goethes Betrachtungs- und Denkweise nehmen wird. Goethe selbst gibt den Grund, warum dieses Werk nicht zustande kam, in den Annalen zu 1790 mit den Worten an: «Die Aufgabe war so groß, daß sie in einem zerstreuten Leben nicht gelöst werden konnte.»

[ 16 ] Wenn man von diesem Gesichtspunkte ausgeht, so gewinnen die einzelnen Fragmente, welche uns von Goethes Naturwissenschaft vorliegen, eine ungeheure Bedeutung. Ja wir lernen sie erst recht schätzen und verstehen, wenn wir sie als hervorgehend aus jenem großen Ganzen betrachten.